Faster travel, shipping, and trade.

Introduction

As the United States began the most deadly conflict in its history, the American Civil War, it was also laying the groundwork for one of its greatest achievements in transportation. The First Transcontinental Railroad, approved by Congress in the midst of war, helped connect the country in ways never before possible. Americans could travel from coast to coast with speed, changing how Americans lived, traded, and communicated while disrupting ways of life practiced for centuries by Native American populations. The coast-to-coast railroad was the result of the work of thousands of Americans, many of whom were Chinese immigrant laborers who worked under discriminatory pressures and for lower wages than their Irish counterparts. These laborers braved incredibly harsh conditions to lay thousands of miles of track. That track—the work of two railroad companies competing to lay the most miles from opposite directions—came together with the famous Golden Spike at Promontory Summit in Utah on May 10, 1869.

The Race Is On

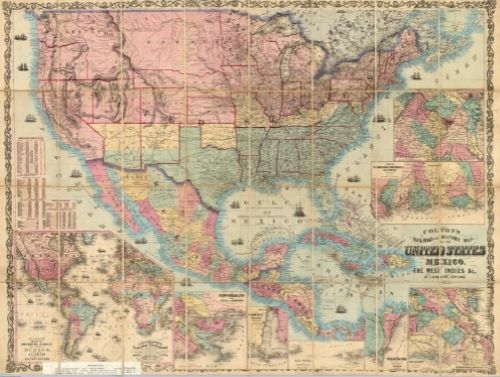

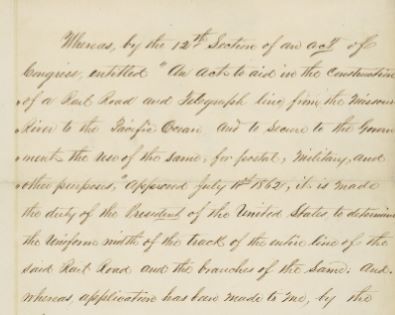

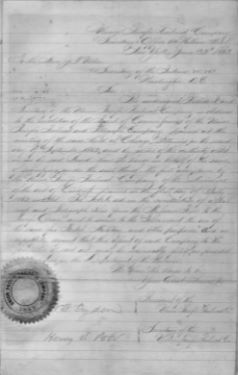

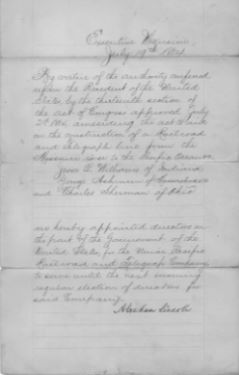

With the discovery of gold in California shortly after its annexation, the untapped wealth of the American West spurred interest in westward expansion at home and abroad. By the time President Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act in 1862 to establish federal support for the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, there was no question that a railway would help people and goods traveling west do so more quickly and safely, with the added benefit of nationwide geographic and economic growth as new towns sprang up near the train’s route.

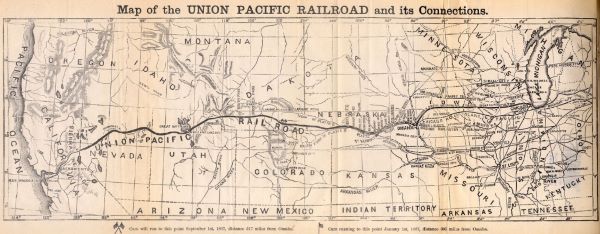

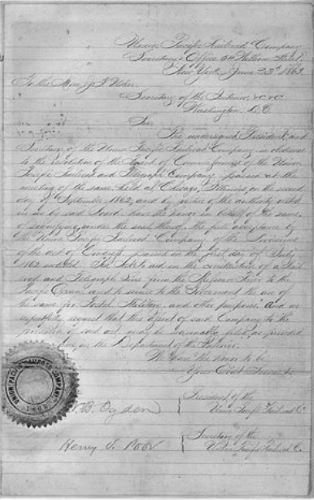

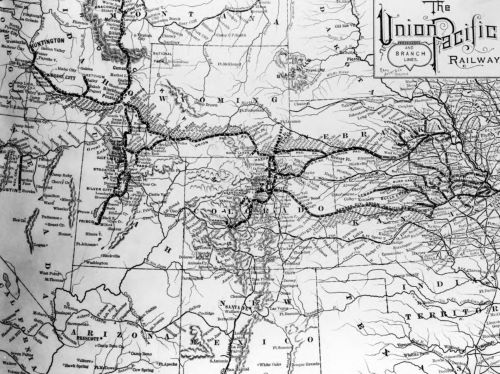

The onset of the Civil War helped decide that route, since after secession, northern lawmakers faced little opposition to a route based in the north. The federal government then contracted the Central Pacific Railroad in Sacramento and the Union Pacific Railroad in Omaha to start laying tracks, supported by government land grants and bonds.

In addition to this support, each railroad company received a bounty for each mile of track laid. The Central Pacific and Union Pacific would each be compensated with $16,000 for each mile of track in the Sierra Nevadas and east of the Rockies. Once the railroads entered the mountains, they would rake in $32,000 for every mile of track they put down. The quicker each company put down track, the more money they would make. This structure of compensation started a seven-year race between the companies to see who could lay the most track.

Hell on Wheels and the Big Four

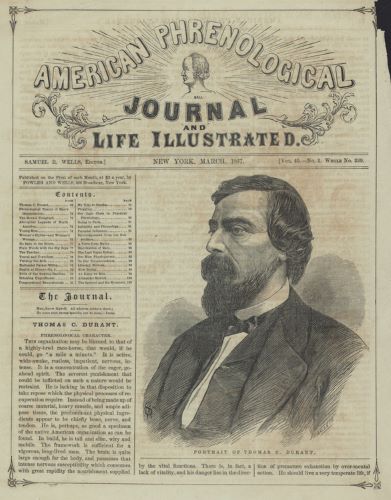

The Union Pacific Railroad Company quickly laid track and racked up miles—and government money. Under the leadership of Thomas Durant, they altered the original transcontinental route to add more miles for profit. Durant also had a habit of withholding wages from the men working on the railway, leading to strikes. It is only fitting that the Union Pacific developed a scandalous reputation and the infamous nickname “Hell on Wheels” for Durant’s tactics, as well as the saloons, brothels, and gambling houses that followed the laborers as they built the railroad.

The Central Pacific was a different kind of hell. The “Big Four,” a group of big businessmen, philanthropists, and railroad tycoons at the helm of the Central Pacific, were looking to turn a big profit, and wanted to ensure that their railroad would connect California to the East Coast. This was by no means an easy task. The Central Pacific was only able to put down 100 miles over the first five years of the project as the steep and treacherous Sierra Nevada mountain range proved to be a formidable obstacle.

Both companies were guilty of trying to lay as much track as possible in order to earn more money—neither wanted to lose even a mile to the competition. However, the race was ultimately a runaway victory for the Union Pacific, which was able to lay 1,085 miles of track to the 690 miles put down by the Central Pacific. Ultimately, the 1,900 miles of track challenged the strength and courage of the tens of thousands of men who laid it hand by hand through rough terrain, difficult climates, and the often unwelcoming populations who lived along its path.

Human Impact

Laborers

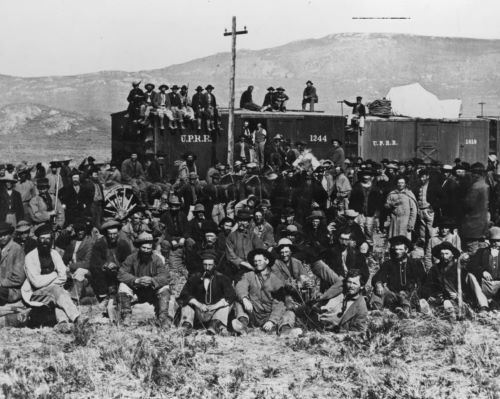

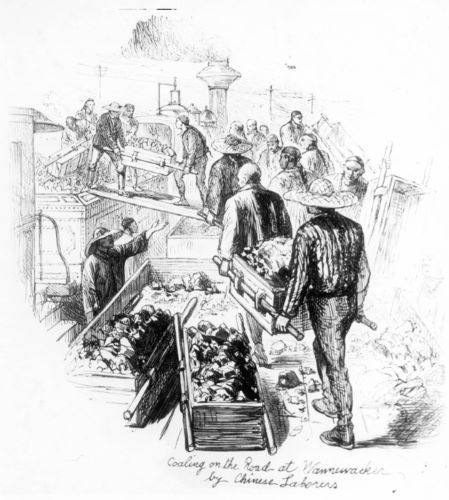

As construction began on the Central Pacific Line, railroad organizers were finding it impossible to retain the thousands of workers needed to lay track. White, mostly Irish, workers would quit after building up savings to seek their fortunes in the gold fields. The Central Pacific questioned where they might find the sustained manpower needed to finish the job.

For them, the answer lay in the Chinese, who had experienced great difficulties in California after emigrating during the Gold Rush of 1849. They were barred from participating in public life, yet had to pay extra taxes. Politicians, notably head of the Central Pacific and Governor of California Leland Stanford, began running on anti-Chinese platforms.

Chinese workers were first brought to railroad work to send a message to Irish workers that they were expendable. Yet work from the Chinese gave the Central Pacific great returns on the meager $30 a month it paid each laborer and thus they eventually comprised 80 percent of the workers on the line. The Chinese would brave the hazardous conditions of tunneling and accomplish incredible feats of track laying, including one period where they put down 10 miles in 12 hours.

A more diverse group was responsible for the construction of the Union Pacific line, including Irish Civil War veterans and newly freed slaves looking for paying jobs in the more progressive West. Mormons also comprised a significant portion of the Union Pacific workforce because of a collective desire to see the railroad incorporate Utah into the rest of the nation.

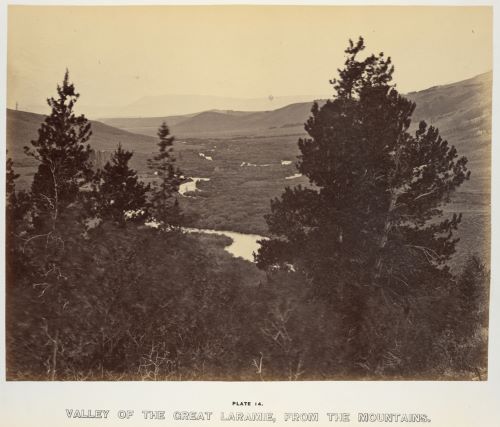

Native Americans

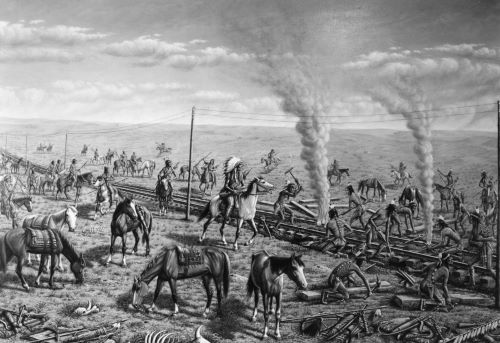

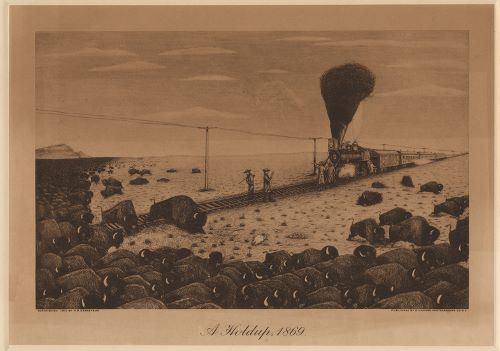

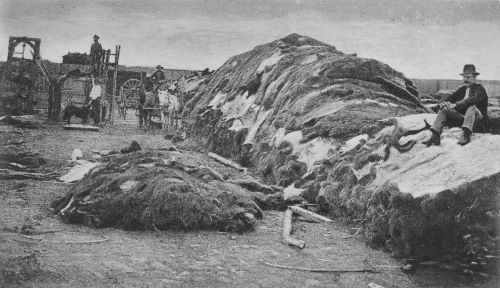

Although, by the 1860s, Native Americans had signed away the rights to much of their land in treaties with the federal government, they likely never imagined that a disruptive and massive system like the railroad would be constructed through their traditional hunting grounds. The construction of the Transcontinental Railroad had dire consequences for the native tribes of the Great Plains, forever altering the landscape and causing the disappearance of once-reliable wild game. The railroad was probably the single biggest contributor to the loss of the bison, which was particularly traumatic to the Plains tribes who depended on it for everything from meat for food to skins and fur for clothing, and more.

Tribes increasingly came into conflict with the railroad as they attempted to defend their diminishing resources. Additionally, the railroad brought white homesteaders who farmed the newly tamed land that had been the bison’s domain. Tribes of the Plains found themselves at cultural odds with the whites building the railroad and settlers claiming ownership over land that had previously never been owned.

In response, Native Americans sabotaged the railroad and attacked white settlements supported by the line, in an attempt to reclaim the way of life that was being taken from them. If they were not taking aim at the railroad tracks and machinery, they would attack the workers and abscond with their livestock. Ultimately the tribes of the Plains were unsuccessful in preventing the loss of their territory and hunting resources. Their struggle serves as a poignant example of how the Transcontinental Railroad could simultaneously destroy one way of life as it ushered in another.

Passengers

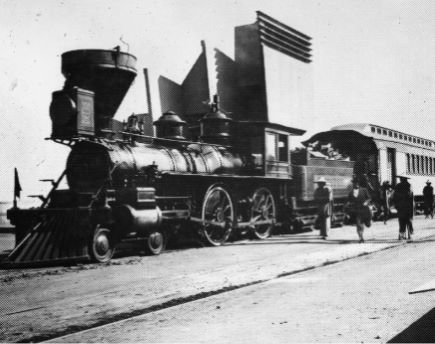

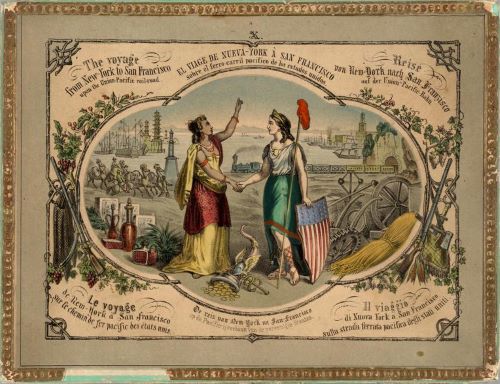

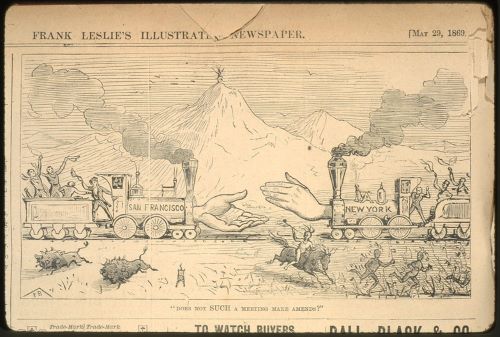

After the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, Americans experienced its incredible impact on travel and migration. Coast-to-coast trips that once took several months now only required a matter of days between San Francisco, on the West Coast, and Chicago, the railroad’s eastern hub.

Passengers marveled at the speed and relative safety that traveling by train afforded them across regions of the country that only decades before were being explored for the first time. Though there were occasional derailments due to shoddy construction, the Transcontinental Railroad was instantly the most secure way to transport passengers and goods to the West Coast and back—far better than by wagon or ship.

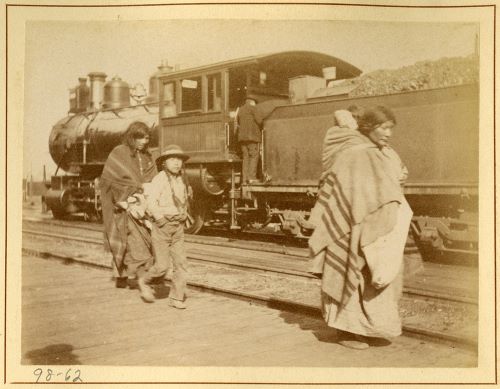

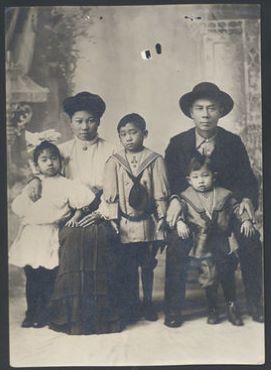

For immigrants to the United States, the Transcontinental Railroad presented an opportunity to seek their fortunes in the West. There, they found more opportunity than the port cities of the East Coast, where discrimination kept immigrants living in urban squalor. The open West and legislation like the Homestead Act of 1862, gave foreigners (and many other Americans, too) the ability to stake claims to their own land, provide for their families, and take control of their destinies in ways that the densely populated East could not. The railroad companies quickly identified these populations as an ideal customer base and developed aggressive campaigns marketing the potential of the West to encourage migration and create more business.

Changing the Landscape

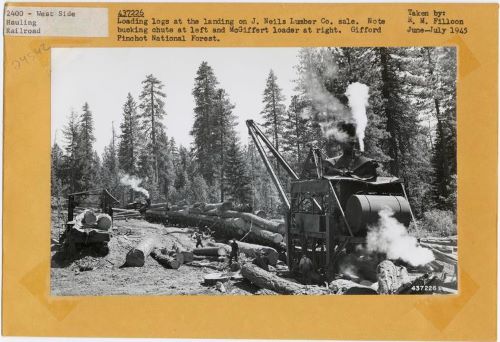

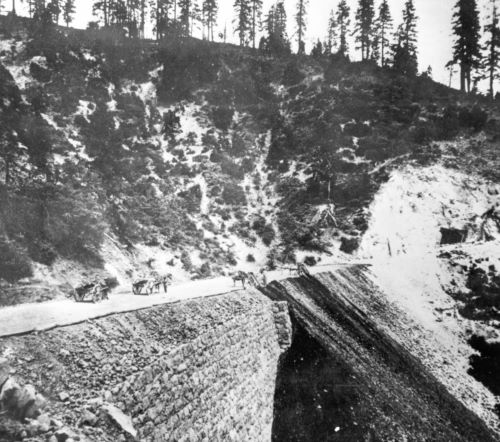

Deforestation and Development

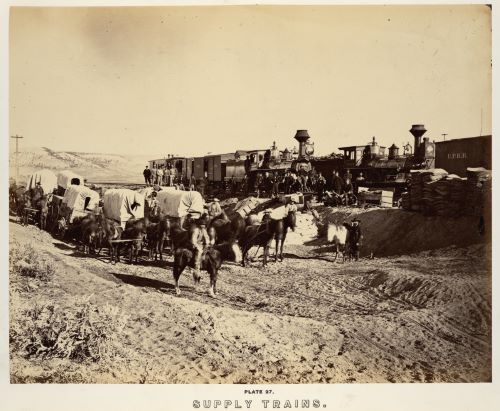

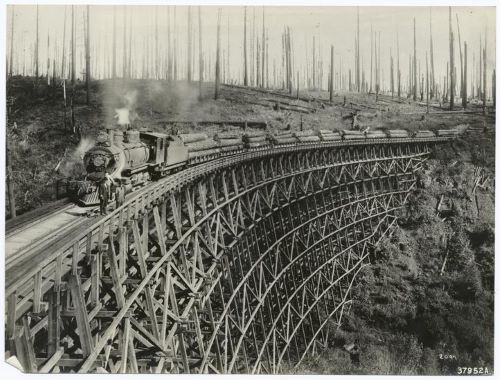

The requirements of building the railroad resulted in significant devastation of the forests of the American West. Lumber was needed for railroad ties, as well as fuel and shelter for workers who needed to cook and stay warm during year-round work on the railroad. Snow sheds, which protected the exposed tracks during the winter months in the mountains, were continuously constructed and dismantled. Support beams for tunnels and bridges were needed to protect workers and the trains.

Even after the railroad was constructed, large amounts of wood were required, including on some areas of track that Union Pacific and the Central Pacific had hastily built and planned to go back and fix. These areas not only led to the derailment of trains, but required more logging to make the necessary repairs.

The train not only enabled the migration of people, it also allowed Americans to conquer terrains and remote environments previously impassable and uninhabitable and goods necessary to support large populations to be shipped with lightning speed. As sparsely populated areas grew into towns and cities, they began encroaching upon once “wild” areas. The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad dramatically catalyzed the development of the West, a process that both extended settlement and mining into otherwise unreachable areas and caused desertification (or, dry and arid conditions) in places along the route.

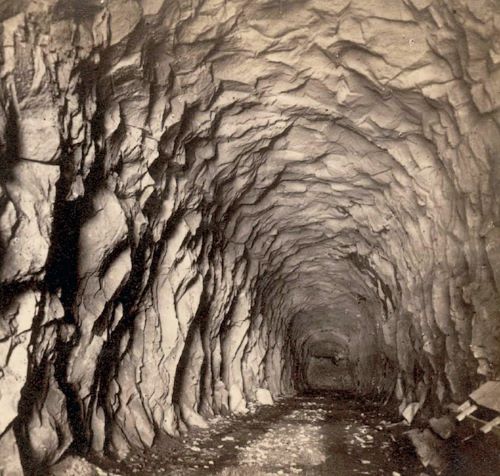

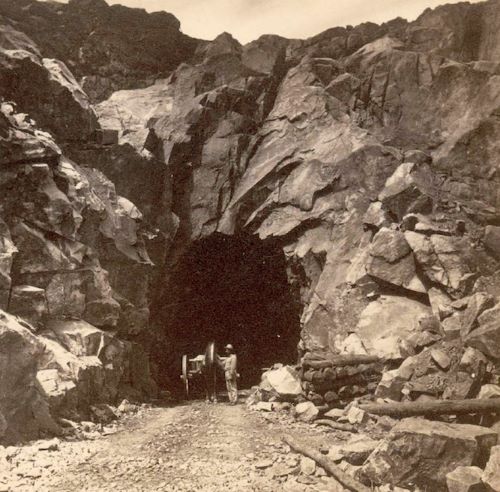

Tunnel Construction

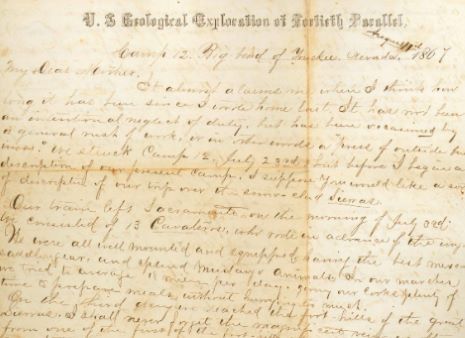

A route through the Donner Pass and Dutch Flats was identified as the safest and easiest route for the Central Pacific Railroad to traverse the Sierra Nevadas. But railroad crews had to find their own way through the mountains when going over or around them was impossible. Over a dozen tunnels were constructed to allow the Central Pacific to pass through the Sierras, requiring thousands of laborers and a great deal of engineering ingenuity.

One of the most challenging tunnels built by the Central Pacific Railroad was Tunnel No. 6, the Summit Tunnel, which ran through the top of the Donner Pass. Early snows defeated the first attempt to build it. While construction crews began digging at both the east and west ends, two additional crews dug down from above the tunnel’s route to pull out the debris through vertical shafts. The measurements used to plan the passage of the Summit Tunnel were so accurate that, having drilled through 1,659 feet of rock, the teams were only two inches off when they finally connected the eastern and western portals.

Another technological advancement that aided the completion of the Summit Tunnel was nitroglycerin. Railroad engineers used this explosive compound mixed on site to move large sections of rock and earth, which was quicker than digging by hand.

The unstable nature of nitroglycerin continued to be a problem during the course of Summit Tunnel construction, causing an untold number of laborer deaths. As a result, it was not used on the remainder of the Central Pacific Line.

A Nation Divided

Fractured Nation

The Transcontinental Railroad was planned and construction began during the Civil War, which gave northern Congressmen reason to oppose plans for a southern route. As southerners resigned their seats in the legislature, Republican lawmakers chose a northern route that would insulate the railroad from the conflict and ensure that northern states benefitted from the line more than their southern counterparts.

Designed to punish the South for the secession movement of 1861, the North’s transcontinental plans had strategic value as well. As the war dragged on, the perception of the railroad as an asset for the North continued to grow.

Although the railroad was not completed until four years after the Civil War, its potential value to the war effort in the North cannot be understated. A completed railroad would have enabled the North to further capitalize on military and economic advantages over the South. Since only 9,500 miles of track had been previously laid south of the Mason-Dixon line, as opposed to 22,000 north of it, the North maintained a large advantage in terms of moving troops, relocating raw materials, and transporting food and other supplies to the front lines.

With a blockade that restricted international shipments of goods and supplies to the Confederacy, southerners were not only prevented from building new railroads, but were forced to pull rails to melt into bullets or to make repairs to more important railway lines.

Uniting the Nation

While the railroad was built in a divisive era, its completion helped unite the nation after the Civil War. Arguably its greatest contribution was that it allowed for people and goods to travel from coast to coast at unprecedented speeds. Prior to construction, cross-country travel required long treks over dangerous land and sea. Travelers could trek for months across the American interior, over the Great Plains, through the Rocky Mountains, and on through the Sierra Nevadas, before ever reaching California. Even by sea, migrants had to spend several weeks sailing around South America and the treacherous Cape Horn before reaching San Francisco. Whereas countless lives were lost by land and by sea, the railroad expedited cross-country travel and made it safer for westward expansion.

The Transcontinental Railroad also served as a strong symbol of American achievement. This was important as the country continued to rebuild after the Civil War. Not only had the US built a transportation system that enabled travel “from sea to shining sea,” but it had also conquered the terrain and the elements of a still wild West.

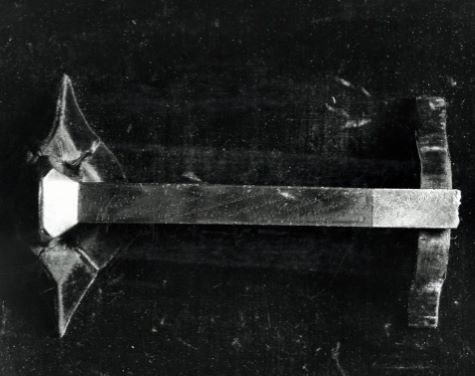

As the country set forth united, railroad workers laid the last railroad tie at Promontory Point, Utah, sealing the ceremony with a gold spike to commemorate the achievement.

The image of the golden spike remains one of the most iconic of the nineteenth century, although an ordinary spike did eventually replace the ceremonial gold one. In fact, the railroad had to replace ties at a rate of one per week as souvenir seekers chipped away at the railroad for a chance to own a piece of history.

A Nation Transformed

The Death of the West

As impressive an achievement as the Transcontinental Railroad was, it also signified the beginning of the end for the “untamed” American West. Hunting for sport became more popular, as passengers on trains hunted herds of bison as they rode across the Great Plains. These train-hunts were designed to both provide entertainment for passengers and to reduce food supplies for Native Americans, who relied on the bison as a staple for survival. Since Native Americans were some of the biggest opponents to westward expansion, lawmakers and railroad pundits alike supported these cruel hunting practices. Unfortunately for both the bison and Native Americans, these wasteful practices were incredibly successful in driving both populations to the edge of annihilation.

The Transcontinental Railroad also commercialized parts of the agricultural west. Forcibly relocating dozens of Native American tribes and seizing their land opened land for pioneer farmers. Areas of the Great Plains that were previously considered unsuitable for farming were reallocated by the Homestead Act of 1862. As a trade for government subsidization, farmers that purchased this new, cheap farmland were expected to work the semi-arid grassland of the High Plains to repay their debts.

Areas that could not be reached by railroad also experienced a sharp decline in population. As the costs of supplying plains and desert communities continued to rise, families moved to greener, more central states. Abandoned communities, isolated by land and resources, created ghost towns across the West. Although the railroad provided opportunities for growth for towns lucky enough to have access, most settlements that relied on wagons to transport goods found that they could not pay the costs necessary to ensure basic survival.

Connection and Exclusion

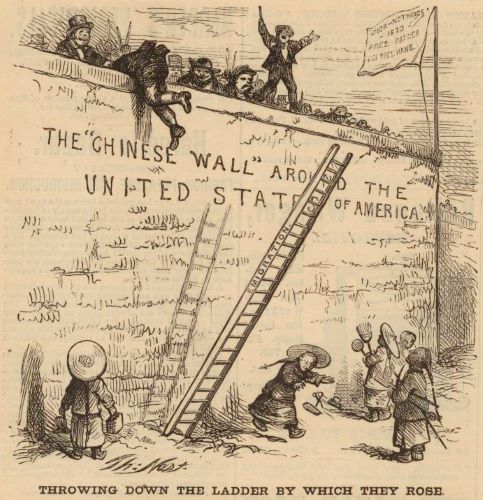

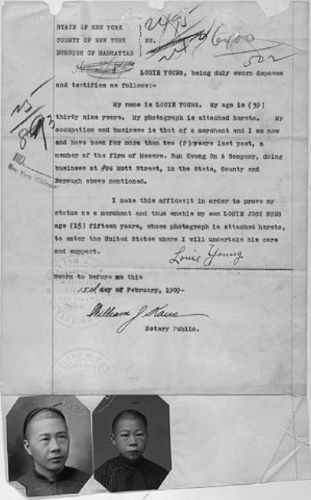

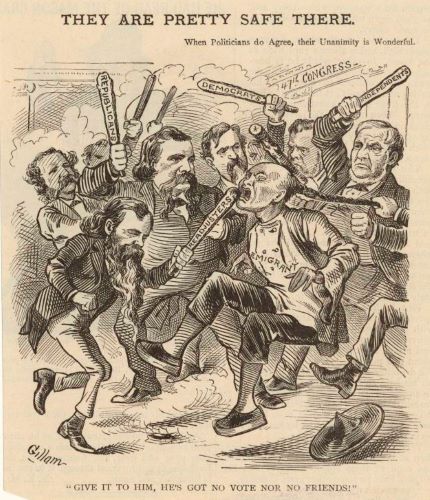

The thousands of Chinese laborers who worked under harsh conditions for low wages, and whose diligence made completion of the railroad possible, were met with a growing anti-Chinese sentiment. Riding a longstanding wave of anger over the perception that Chinese workers (and their low wages) were taking jobs from Americans, the Chinese Massacre of 1871 resulted in an angry mob hanging seventeen Chinese men and boys in Los Angeles.

In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was signed into law, putting severe limits on both the number of new Chinese immigrants allowed into the country and those who could become naturalized citizens. Anti-Chinese mobs would continue to enact violence for years to come.

While the anti-Chinese movements brought out the worst in Americans, the Transcontinental Railroad did create opportunities for communication and knowledge sharing never before possible. Poems, including Walt Whitman’s “Passage to India,” novels, and films were inspired by the new possibilities of the cross-country railroad. News, scientific discourse, and culture could travel from one side of the country to the other at new speeds. So could goods, with $50 million in freight traveling the rail line in its first ten years of operation.

With the success of the original transcontinental route, tracks were laid to connect even more parts of the country. That original route, however, is still partly in use today. The Amtrak “California Zephyr” train travels via the first Transcontinental Railroad from Sacramento to Nevada.

This exhibition was created as part of the DPLA’s Digital Curation Program by the following students as part of Professor Krystyna Matusiak’s course “Digital Libraries” in the Library and Information Science program at the University of Denver: Jenifer Fisher, Benjamin Hall, Nick Iwanicki, Cheyenne Jansdatter, Sarah McDonnell, Timothy Morris and Allan Van Hoye.

Published by the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), May 2015, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.