In some ways, this is a history of an intellectual cul-de-sac.

By Dr. Dina Gusejnova

Associate Professor, Department of International History

The London School of Economics and Political Science

Introduction

The modern history of Roman law has been frequently associated with Western European political integration. Legal and intellectual historians have repeatedly looked at the geographical spread and intellectual lineages of Roman law to assess the degree of Westernization in different polities, from the Russian Empire to the British Isles.1 By discussing the reception of Roman law as an aspect of the political thought of an exile from Bolshevik Russia, I hope to flesh out one of its less prominent uptakes in the intellectual culture of Europe, as a source of inspiration for Russian international law and what remained of it after the demise of the Russian empire.2 While the broader framework of this story reaches from the last decade of Europe’s Continental empires to the start of the Cold War, I am particularly interested in the way elements of Roman law were invoked in intellectual debates around the First World War and in the interwar period. At this time, revolutions shook not just particular empires, such as the Russian, but the legitimacy of imperial rule as such.

My main case study is the intellectual biography of Baron Mikhail von Taube (1869‒1961). In some ways, this is a history of an intellectual cul-de-sac. Born in the imperial residence of Pavlovsk near St. Petersburg, Mikhail von Taube, or Michel de Taube, as he was known in France, was a Russian subject, of Swedish extraction, German-speaking yet, unlike most Baltic Barons, neither Protestant nor Orthodox but of Catholic faith. By the age of thirty-five, he could already look back on a stellar career: He was professor of international law, succeeding his renowned teacher Fyodor Martens in this post; he worked in the Russian foreign office on highly visible cases of international dispute, including the so-called Hull Incident when a ship of the Russian Navy had accidentally fired on private fishermen off the British coast, and several other major naval incidents involving conflicts with Venezuela, France and Italy. By the second year of the Great War, he had become senator, and a year later, he was promoted to the role of deputy minister for education and a member of the State Council of the Russian Empire. His international career was no less outstanding. In 1913, he was among the dignitaries who inaugurated the Hague Peace Palace, a crowning achievement of the field of legal scholarship he and his teachers had represented, and served as a judge in major disputes before the First World War broke out.3

In 1917, however, Taube’s career as a public civil servant, like that of many leading Russian intellectuals of his time, ended abruptly, as the Russian Empire disintegrated during a decade of civil war, during which the Soviet Union emerged as a new type of republican federation in 1922. In 1918, Taube was briefly asked to serve as foreign minister of the Russian government in exile in Finland, a post which soon evaporated, leaving him with a modest academic career and the prospect of working as a private lawyer for other exiled aristocratic families.

The ruptures to his personal intellectual trajectory reveal new aspects of Europe’s political transformation. As the Bolsheviks declared a war on legal systems resting on private property, there was no longer a place in Russia for lawyers of Taube’s bent. Later, the Soviet authorities developed new understandings of sovereignty and international law.4 As Lenin had put it, just as ‘capitalism’ was only permitted at state level in the Soviet state, it would admit no ‘private law’ and repeal the old form of ‘private contract’, which he called a ‘corpus juris romani’ (Lenin 1924). Instead, Lenin demanded the introduction of a ‘revolutionary legal consciousness’. In assaulting earlier publications on Roman law, Marxist legal theorists like Evgeny Pashukanis believed that it would eventually be possible to develop an alternative legal system not resting on private property.5 German communists like Alfons Paquet also argued that ‘war should be declared on the contemporary civilization which rests on Roman foundations’. He also blamed Roman law for the heightened struggle between nations which led to the collapse of all morality (Paquet 1923: 872‒3). At around the same time, in Germany, the notorious Article 19 of the NSDAP called to replace the ‘materialist’ ideas of Roman law with old ‘German common law’ (ein deutsches Gemeinrecht), an idea which the Nazis began to put into practice partially, but particularly, in the context of the recolonization of Eastern Europe (cf. Landau 1989: 11‒24). For all their ideological differences, both new regimes, the Soviet Union and later the Third Reich, made their hostility towards Roman law into a cornerstone of their respective legal policies.

Among lawyers of different political orientation, these juridical as well as political upheavals associated with the Soviet and the Nazi regimes elicited a widespread search for new foundations of European legal culture. Roman law and its reception served as a key intellectual resource for exiled lawyers of a wide range of political orientations, and Mikhail von Taube was one of many contemporary lawyers who contributed actively to this search. A biographical perspective can shed light on the divergent agendas which governed ideas of Roman law in its twentieth-century contexts and the adaptability of concepts to situational needs.6 In the mid-twentieth century, references to Roman law can be used as a litmus test for understanding intellectual developments in the face of new quasi-imperial ideologies which grew in eastern and central Europe.7 Legal scholars whose careers have been described as interrupted or uprooted mostly hailed from parts of Europe occupied by Nazi Germany.8 However, most historians examine the trajectories of lawyers in exile in twentieth-century Europe through the eyes of refugees from Nazi Germany and adjacent territories. Taube represents a different group of exiles, one for whom Nazi-occupied France and Germany under Nazi rule functioned as a place of refuge from the Soviet regime. One of the consequences of his situation was that his legal thought was not absorbed into the canon of Anglo-American thought on international law, which is associated with other émigré figures such as Hans Kelsen and Hersch Lauterpacht.9 Though he was no committed Nazi, Taube was loyal to the regime. Arguably, this makes his case all the more fascinating among the more familiar examples of ‘uprooted’ jurists.

In the next section of this chapter, I will provide an outline of the relationship between ideas of Roman law and notions of the frontier between East and West, before placing Taube in this context. The final section focuses on Taube’s changing ideas of legal international order after 1917, and analyses in what way it presented as a turning point for his political thought.

Roman Law as a Russian Concept of Western Civilization

By the end of the nineteenth century, the legal profession in the Russian Empire was dominated by the German historical school, which envisaged the geographic spread of ‘civilizing ideas’ from west to east.10 Liberal intellectuals in Russia idealized the Western tradition, and many had studied at German universities. In Russia, Roman law was embedded in the legal curriculum of the universities of Moscow, Kiev, Yur’ev and Yaroslavl’, where this legal heritage of ancient Rome was used to identify gaps in Russia’s own legal landscape. Rome, argued Vladimir Guerrier, a Russian constitutional monarchist, ‘having lost a world’, came to ‘rule in the sphere of ideals’. The original, ancient Rome lost its empire, restored it in Constantinople as the ‘second’ Rome before remaining instead purely as an ‘empire in the realm of spirit’.11

The idea of Roman law has been used to define concepts of the West both in Western and in Eastern European scholarship, but the precise nature of their relationship has been conceptualized in very different ways.12 For German and French jurists and historians of the early modern and modern era, lineages of Roman law allowed them to demarcate a longue durée transformation of ancient empires into the civil societies of modern imperial nations and then nation states in Continental Europe, a transformation which evolves around the codification of a Corpus juris civilis. After the demise of the last European empire presumed to have been built on its foundation, the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, the French and the German civil codes were treated by scholars as the closest incarnation of Roman law in the modern era. Thus by 1900, it was the German cultural sphere, which Tacitus had once so influentially defined as ‘barbarian’, that came to epitomize the most effective application of Roman law to a modern civil code, leading, as one textbook has put it, from ‘Justinian to the BGB [Bu ̈rgerliches Gesetzbuch]’ (Rainer 2012).

Russian admirers of Roman law presented it as an essential element for enabling the transformation of empires into modern nations. In its function as a force of integration for civil society, Roman law was also seen as a repository of regulating civil relations. As such, Roman law outlasted not just the Roman empire and its successors, but also numerous other states which had embedded it in their jurisdictions. However, this wide range of applications also meant that ‘too much’ civil law had the potential of rendering powerful governments superfluous. In Russia, the infamous ideologue of Russian autocracy, Konstantin Pobedonoscev, had written an influential set of monographs on the history of civil law, in which he explained the necessary limits for the application of Western models to Russia (Pobedonoscev 1871, 1873, 1880). By contrast, his liberal critics such as Vladimir Nechaev and Iosif Pokrovsky did not miss an opportunity to point out that the future of Russia’s constitutional development depended on the availability of legal knowledge in its Western European form, some of whose proponents, such as Konstantin Nevolin, had been exiled for much of the nineteenth century.13 The fact that Rome and Roman law were hotly contested concepts in late imperial Russia can be seen in various entries of the renowned Encyclopaedia Brockhaus and Efron (1896‒1907), including ‘Rome’, ‘Roman law’, ‘Corpus juris civilis’, ‘Codification’ (Kodifikatsia) and ‘civil law’ (grazhdanskoe parvo). These entries not only represented a wide range of disciplinary perspectives, from archaeology to jurisprudence, but also served as a foil for laying out a range of political agendas, from constitutional monarchism to Marxism (ESBE 1890‒1907). Roman law was also placed in relation to European political thought on international relations, particularly starting in the early modern era, epitomized in the work of Hugo Grotius and others (cf. Gordley 1991; Mälksoo 2012a,2015).

Perhaps the least contested sphere of Roman law in Russia was international law. Scholars in Russian intellectual circles beyond the legal profession were influenced by the arguments of authors such as Rudolf Sohm and Rudolf von Ihering. Elements of Roman law had permeated particularly in the domain of inheritance law not only in the Baltic region but also in parts of what is now Ukraine and Poland, which might explain the high number of civil lawyers from this region. But upon closer look, there were significant differences both in their intellectual trajectories and in their understanding of law. For instance, one lawyer who specialized early in the Baltic region’s legal exceptionalism was Axel Freytag-Loringhoven; his interest in the Germanic roots of some Baltic legal systems eventually encouraged him to seek a career in Germany, where he became a high-flying publicist of Nazi ideas of Lebensraum.14

Scholars of German–Baltic background were prominent among the administrative elite of the Russian Empire (cf. Holquist 2006). Sociologically speaking, many teachers of civil law were intellectuals of non-Slavic background. Many of them had a complex relationship to the anti-Western and Pan-Slavic elements of Russian society as well as to German intellectuals in Prussia (Mälksoo 2015: 42‒7). During the revolution of 1905, driven by nationalist and socialist movements in the Baltic region many representatives of this region’s elite articulated their commitment to Roman law as a civilizing force in this area, which was threatened by the revolutions.15 Against the tendencies of Russification at the level of education and civil administration, they were intent on maintaining their own ideas of sovereignty against rival claims to power from Russia’s autocrats, on the one hand, and from its peasant or vernacular populations, on the other.

Russia was, of course, still an autocratic state, but one with a newly found outward ambition to shape soft power discourses alongside wars and conquests. In 1898, Tsar Nicholas II invited fifty-nine sovereign states to the Hague International Conference of 1899. Even as late as 1914, ‘Russia’s proposals for the next peace conference’ continued to be discussed in the British liberal press.16 For all their differences, the last Tsars, the two Alexanders and Nicholas II, sought to increase Russia’s international standing as a beacon of international law, not only through wars with the Ottoman Empire in defence of ‘Christendom’ but also by laying institutional foundations of a certain type of peacemaking which could be useful as means for regulating property and the control over territory in wartime.

The leading names in the emerging Russian tradition of international thought ‒ Friedrikh Martens, Baron Boris Nolde and Mikhail von Taube – were of Baltic background (Martens 1883; Mälksoo 2014). Taube belonged to the establishment of an international community of lawyers who had been intent to devise new, positive foundations for a civilizing European international law that transcended even Europe’s Roman legal past, as Martti Koskenniemi has argued (see Koskenniemi 2001). Taube’s widely used textbook on international law examined its key principles and historical foundations from the second century CE to the Reformation.17 His wide chronological framework and the focus on Eastern Europe challenged the conventional narrative of the origins of European international law with its emphasis on Hugo Grotius and the Westphalian order of seventeenth-century Western Europe.18

In this work, Taube developed the conjecture that even though the concept of jus gentium originated in Justinian’s code, there was no ancient or medieval international law as such. Nonetheless, the history of legal practices in some places resembled modern international law. These examples of good practice were more likely to be found in empires than in unitary states. Taube emphasized that it was the papacy, with its use of canon law designed to uphold imperial power in Byzantium, which saved Roman law for subsequent uses in international law. Christianity, in his view, had rendered Roman law more universal in aspiration than it had been when the Roman Empire itself was in existence. In the light of Taube’s conception of empire and hegemony as a benign force in international law, the year 1917 signalled profound crisis to his political thought.

‘Pacta sunt servanda’ and the Interwar Crisis of International Law

The ‘twenty-year crisis’ famously identified by E. H. Carr was particularly visible in the European legal tradition, where new sources for realist responses to the challenges of the day were not self-evident.19 For many scholars of law from areas such as Eastern Europe and the Baltic, the crisis not just was intellectual but also affected their livelihood, as they experienced various tectonic shifts in their professional lives (Mälksoo 2015). The uncertain nature of their social and political contexts makes many individual cases appear isolated. They resist any ‘emplotment’ in terms of either normative or deviant paths of intellectual development in relation to the Nazi or Soviet ideologues or their overt critics.

Just as for these other lawyers, his preoccupation with Roman law served Taube as a source of continuity amidst a changing, post-imperial legal landscape. The nineteenth-century German Romanists like Rudolf Sohm had suggested that already in Antiquity, Roman law had evolved from a city law of the republican era (Stadtrecht) into a global civil law (Weltrecht) under the empire’s universal aspirations.20 For Ihering, similarly, the essence of Roman law remained its spirit and its codifications rather than the institutions it served (von Ihering 1852, 1854, 1858). This notion that Roman law could be applied on a modest, pragmatic scale, as well as being open to claims to global or at least universal power, provided an opportunity to legal internationalists of different political orientation, but as we shall see below, it was particularly appealing to Mikhail von Taube.

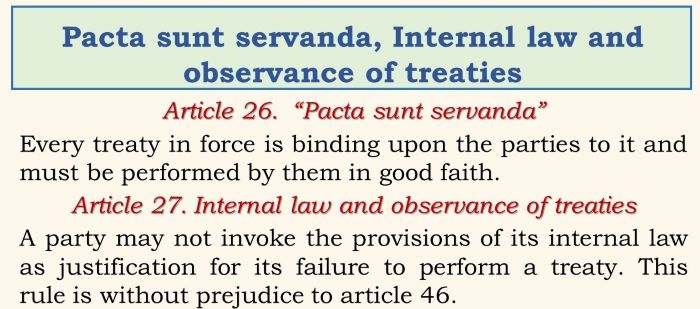

Taube’s key contribution to the interwar crisis of the law was an attempt to revisit the concept of the inviolability of treaties, which is embedded in the Roman concept pacta sunt servanda. In the absence of any stable authority or fixed notions of sovereignty, these notions of trust had to be relied upon in order for society to move forward. As Taube put it, ‘Pacta sunt servanda, tel est, de temps immémorial, l ́axiome, le postulat, l ́impératif catégorique de la science du droit de gens.’21 In his view, the sanctity of pacts derived from their original, religious function as covenants in ancient societies, rather than from the practice or codified norms of contractual exchange. The phrase, in this sense, was not a norm but a kind of golden rule, which suggested that rules be followed. Unlike Hersch Lauterpacht, who alluded to John Milton’s critique of the Presbyterians in the English Civil War, when he suggested that international law was often ‘but private law “writ large”’, Taube placed this phrase from canon law in a different genealogy, to describe treaties between unequal partners and in the absence of a common civilizational core.

As in earlier work, Taube now demanded that a ‘minimum of juridical relations’ – the existence of a kind of informal civil society, a common sense ‒ was necessary in order to make agreements possible. He had developed this concept in a revised version of his work on the Christian and medieval foundations of international relations, now called Perpetual Peace or War Everlasting?22 He believed that this juridical minimum could only stem from spiritual, not from purely economic forms of intercourse – an idea which gained further weight in the publication thanks to a facsimile of a letter of support he had received from Leo Tolstoy in 1902 (Taube 1905). The central author for Taube was Thomas Aquinas, not Hugo Grotius.

However, precisely to what end Taube may have wanted to put his theory – in other words, in the hands of which governments or which organizations – was not immediately apparent from his written work. He presented it to the legal community at the Hague; yet Taube’s own political affiliations had gone through various permutations by the time this article appeared and were not easily accommodated within the largely Protestant-influenced Hague Academy and its partner, the Carnegie Foundation. The initial picture of Mikhail von Taube’s situation after the October Revolution of 1917 is one of multiple alienation. After a brief spell as the appointed minister of foreign affairs of the Russian government in exile in Finland, headed by Alexander Trepov, he went on to teach briefly at Uppsala University in Sweden, before moving to Germany and then France.23 In contrast to the liberal language of the Hague Academy of International Law, Taube’s golden age was the pre-Mongolian period of Russian–Western approximation (see Taube 1926a,b). Here, he differed from the other Western-oriented European jurists like Charles Lyon-Caen, Nicholas Politis and James Scott.

In 1921, in addition to his lecturing commitments, Taube had joined informal associations committed to the reinstatement of monarchy in Russia. These included the Munich-based Wirtschaftliche Aufbau-Vereinigung, which was an association of German Nazis and Russian Monarchists, and included Alfred Rosenberg, who would later become one of the most influential ideologues of the Third Reich and Reich minister for the occupied territories in the East.24 ‘White’ Russians from the Baltic region were particularly prominent there. In 1931, he was invited to teach at the University of Münster in Westphalia, a job he carried out until 1939, lecturing on international law.25 In 1937, like most other professors, he made an oath of allegiance to Hitler, having reassured the rector in a note that he believed this oath of a ‘former Russian subject of German extraction and State Minister would not be in contradiction to an earlier pledge of honour made to the Imperial House of the Romanoffs’.26 At a time when most prominent exiled lawyers of his generation were in exile from the Nazis, Taube chose Paris under Nazi occupation as his destination.

In the 1930s, Taube became affiliated with the initiative of another exile from Bolshevik Russia, the artist and guru Nikolai Roerich, who used to be identified as a Catholic before discovering a blend of oriental religions later in life.27 He was one of the initiators of a movement to protect cultural heritage in times of war. The Roerich Pact was based on the encouragement extended to governments to sign agreements for the mutual protection of cultural heritage sites. Between 1929 and 1933, according to Roerich, more than thirty national societies for the protection of cultural heritage had been set up (Andreyev 2014: 340‒1). The organization was also linked to the League of Nations, the Carnegie Foundation and to US President Roosevelt personally. Roerich believed that the symbols of his flag, three red dots on white background, would function like the Red Cross and indicate neutral territory over cultural goods. Taube ran the French society, together with a French admirer of Roerich, Marie de Vaux Philipau, and another Russian émigré, George Shkliaver, out of Shkliaver’s apartment. Both Catholics, Philipau and Taube were especially active in establishing ties between Roerich’s organization and the Catholic institutions both in France and in the United States.28 Taube’s collaboration with Roerich’s ‘pact’ – a soft power organization, as it would be called to day ‒ was the closest practical application of his interpretation of pacta sunt servanda that I have been able to find.

In sum, during the interwar crisis of European politics, Taube is particularly difficult to pin onto clear ideological patterns such as ‘progressive’ and ‘reactionary’, ‘white Russian’ or ‘anti-Nazi’. Yet, it is the difficulty of making sense of his ideas in context that is illuminating. Unlike other émigrés from Russia flirting with the Western European right, Taube remained detached from the Eurasianists, whose image of Byzantium was that of an anti-Western cultural polity.29 Russian thinkers traditionally preferred an ‘eastern’ perspective on the Roman Empire, focusing on the Byzantine Empire as an antidote to the Roman path of Western European development.30 Taube fit neither the German historical school’s vision of Roman law nor the ‘Byzantinism’ of his fellow Russian thinkers like the philosopher Vladimir Soloviev or the linguist Nikolai Troubetskoi, who emphasized Russia’s historical distance from the West (Wiederkehr 2007).

The interwar years were also a time when Taube became concerned with the question when Russia had entered its deviant path towards what he called the ‘great catastrophe’ (Taube 1928; Taube 1929). At this point, he had crossed a wide range of social and political worlds, which many of us today tend to think of as politically and conceptually separate. He was fiercely loyal to Europe’s most autocratic regime associated with the Romanoff family, until their execution in 1918 in the wake of the revolution. Yet, he upheld a strong belief in the importance of what we might call the horizontal fabric of power, rooted in the notion of the sanctity of treaties. The ideology of the empire he served was entailed in triad, formulated by Sergei Uvarov, of ‘Autocracy – Orthodoxy – Folk spirit’.31 He saw his work at the Hague as continuing in the spirit of the Holy Alliance. His main opposition was to the Protestant internationalism of the territorial nation states of Western Europe, a consequence of the great schism of 1045. The latter, in his view, affected the Western world more than of the East, where a new state, the union between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Catholic Poland, as well as further pacts in the Baltic region, promised a rapprochement with the Catholic west. By contrast, the period of the high Middle Ages – before the invasion of the Tatars – was, for him, the closest Europe had come to a ‘Respublica Christiana’. Unlike his contemporary ‘Byzantinists’ such as Konstantin Leont’ev, who insisted on irreconcilable differences between Orthodoxy and the West, he thought that Russia’s recovery would come from a reunification with Catholicism under a strong emperor. Even in the twentieth century, he thought, the cities of Central and Eastern Europe, like Vilnius, Warsaw and Lemberg, remained important religious and cultural centres. He liked to contrast them with Muscovy, which, with its false pretences of being a ‘third Rome’, had become a sort of dystopian capital of the ‘Third international’ (Taube 1938: 46).

Like other displaced legal scholars from Central and Eastern Europe, including Hersch Lauterpacht, Raphael Lemkin and Vladimir Hrabar, Taube turned to international law and its sources in Roman juridical concepts as a source of orientation.32 Taube’s professional training in international civil law enabled him to maintain a professional career even after the empire whose ‘indestructible historical foundations’ he had announced in late 1915 had collapsed in 1917 (Taube 1915: 60). Yet, the points of orientation for his work had fundamentally changed. For another four decades, he continued practicing international law by teaching at the universities of Uppsala, Louvain, the Russian university in exile in Berlin, the Hague Academy of International Law, and the University of Münster, as well as making a living as a private genealogist in Paris. However, as I want to show in the next section, to analyse Taube’s turn to Roman law solely as a reaction to the events involving the Soviet and Nazi regime would leave us with an incomplete picture of his interpretation of Roman law’s relevance for international law.

Two Views of 1917: Sovereignty without Territory

If the collapse of his empire following the year 1917 inspired Taube’s work on ‘pacta sunt servanda’ as the juridical minimum of international relations, another concept of Roman law was inspired by a more ‘intellectual’ set of events of that year. In 1904, Pope Benedict XV had commissioned Cardinal Gaspari to produce what is a new Code of Canon Law, a compilation which some have compared in significance to Justinian’s Digest. (Whether or not this is an exaggeration only the future can tell.) This was finally completed in 1917. (In fact, it is now known as the 1917 Code of Canon Law.) The Canon enabled the Vatican to sign a record number of agreements with new post-imperial governments in Central and Eastern Europe, including Lithuania, Poland, Czechoslovakia, as well as to work in a clandestine manner within the Soviet Union as well. Special funds were used via the papal legate Eugenio Pacelli to bring together émigrés from Russia, Ukraine, Poland and other Eastern European countries in a common struggle against Soviet communism.33 Taube belonged to this group informally but also published an historical essay in a volume edited by Ludwig Berg, an aide of Pacelli’s.34

As a Catholic, Taube had an additional reason to develop an historical sense of distance from the – already conflicting ‒ historical teleologies upheld, respectively, by the Baltic German elite, the Panslavists, as well as by the liberal Westernizers.35 Taube reverted this genealogy, which was widely promoted particularly by institutions such as the League of Nations, according to which we progress from the law of the medieval Italian municipal communities, to the law of peoples of the time around the Thirty Years’ War, to the Enlightenment models of Vattel, Kant, and so forth, and eventually, the Geneva conventions and the United Nations (and in the present day, authors like Rawls).36 But the other notion that Taube sought to revive in this context was ius interpotestates. The background to his interest in this concept was Taube’s renewed engagement with Catholicism, this time, as a political movement of resistance to Soviet expansion.

In doing so, he pointed to the centrality of Roman and canon law as the moments in European history when the connection between church and empire was at its strongest. He championed Byzantium not because it was eastern but because it was the main source of civil – Roman and canonical ‒ law. Having been the architect of the Russian Tsar’s peace and education projects whose Catholic faith had been a private affair, he now turned into a more active theorist of Eastern and Western European Catholic unity. As a Catholic, Taube had belonged to a minority in the Russian Empire, but during his exile in Western Europe, his Catholic faith and the experience of interfaith communication proved to be a point of connection. In 1936, in Warsaw, Taube additionally published a collection titled Agrafa, a compilation of the uncodified sayings of Jesus geared to contribute to a consolidation of Christian faiths in the twentieth century (Taube 1936).

Taube’s political loyalty belonged to the autocratic and Orthodox dynasty of the Romanoffs, but as a legal historian and theorist, even in this period of his life, he produced influential accounts on the transmission of Roman law through canon law, particularly, in treaties and relations between the early princes of medieval Rus’ and their Western contemporaries (Taube 1933). He rejected the post-Westphalian teleologies of international law which other international jurists such as his teacher Martens subscribed to, and which he associated with Protestantism, believing instead that the Pope possessed a form of sovereignty which enabled the emergence of a type of legal regime which was different from ius interstatum or ius gentium because it implied the possibility of a potential global sovereignty without territorial control. As Taube put it, in fact the role of the Catholic Church in the modern world calls for a ‘juridical category of its own’, which he proposed to call droit entre pouvoirs or jus inter potestates, specifying that by ‘potestas’ he meant not only a Hobbesian territorial state but also a non-territorial form of sovereignty. This non-territorial form of sovereignty, in his view, preceded the Westphalian political order of the seventeenth century. Its provenance was what he called ‘deux sciences fondamentales de la jurisprudence d’autrefois’ – ‘du droit canonique et du droit romain’.37

In Taube’s view, the Western Europeans were mistaken in seeing the power of Roman law in territorial forms of sovereignty. He believed that the classical expression of sovereignty, the notion of non-recognition of a superior power [superiorem non riconoscere], which began to proliferate in the early modern period, was mistakenly only applied to territorial power. In the interwar period, a group of Russian émigrés in Germany had formed an intellectual community whose aim was fostering ties between Catholic and Orthodox faiths. Taube contributed a book to a series in their publishing house, in which he argued that any territorial power was ultimately more ‘ephemeral’ than spiritual power. The aspirations of Constantinople to become the Second Rome, or of Moscow to serve as the Third, were therefore mere hubris (Taube 1927). Moscow’s attempt to defeat the other imperial powers in the Crimean war had failed in 1853. But Taube was optimistic about the prospects of a united Church. In his view, the task was to recall the survival of the ‘first’ (and timeless) Rome of the ‘Respublica Christiana’, therefore, which would outlast ‘Nero and Attila, the Saracenes and Normans, the Byzantine kings and German emperors, Luther and Voltaire, Napoleon and Garibaldi, the empire of Protestant Berlin and the empire of Orthodox Petersburg’. In what was an unusual intellectual move, Taube looked East and not West to recover unity among the Christian churches, at Russia from the period before the Mongol invasion.

Conclusion

Taube’s work as a jurist in the interwar period did not have even a fraction of the impact of other international lawyers who were displaced or uprooted in the twentieth century. Hersch Lauterpacht’s conception of international law, and his reading of Roman law in this context, with the centrality of the individual, prevailed as the more influential engagement with this heritage.38 Some of Taube’s model of a benign imperial hegemony was out of sync with his time. But even those activities which could have had more resonance, such as the Roerich Pact, the organization for the protection of cultural heritage in wartime, ultimately remained little known, since this organization was absorbed by UNESCO after the Second World War. Nonetheless, his work, the way he adapted to the uncertainties of political exile and the social process by which his career was ultimately disrupted, are emblematic of a wider cultural history. The fading empires of his present provided Taube with a foil for recalling how Roman law had been used to consolidate the Byzantine Empire.39

It was somewhat ironic that the tenure of this professor who specialized in the sanctity of treaties ended in the year of the Hitler–Stalin pact – an agreement which, apart from being unjust in its treatment of peoples to be subject to a shared Nazi–Soviet hegemony, was soon broken. The case of this twentieth-century peregrinus with his experiences of statelessness and shifting allegiances provides a fascinating window on this period in European social and cultural history.

Yet, alongside imperial dissolution and catastrophe, the year 1917 had also ushered in a new codification of canon law which held the promise of a future union of Christians. Had he lived until the 1990s, Taube might well have concluded that the idea of breaking down communism under the umbrella of the Catholic Church through separate pacts with nation states and subnational groups was ultimately successful, considering the rise of civil society in Eastern Europe from the 1970s onwards and the role of the Church in this context.

In 1929, the Russian medievalist Pavel Vinogradoff in Oxford called the medieval history of Roman law a ‘ghost story’ set in dark times, when the demise of the Western Roman Empire coincided with an era of legal decay across all of Europe, having to wait a long time to return to earth (Vinogradoff 1929: 4). A similar spirit prevailed among lawyers who found themselves displaced or, indeed, uprooted in the mid-twentieth century. In practice, it was not at all clear to what extent the ideal of Roman law as civil law could still be upheld in the age of new rising empires which constantly broke the norms of international pacts, from Brest-Litovsk to Molotov–Ribbentrop (Anzilotti 1902). The example of the princes of early medieval Rus’ served him as a repository of historical experience for uncertain times. But, set against the youthful imperialism and internationalism of the Nazi and Soviet anti-Romanists, this ‘Byzantium’ was emphatically a country for old men.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Most influentially, of von Savigny 1840; Pokrovsky 1917; followed by Levy 1929; Vinogradoff 1929; Koschaker 1947, and most recently, Avenarius 2004 and 2014. See also Caenegem 1991.

- For an outline of this perspective from the modern point of view, see, for example, Bunce 2000.

- See Taube 1929, 2007. See also a review of Taube’s reflections on Russian politics before the revolution by Hans Wehberg (Wehberg 1931).

- On Soviet international law, see Grabar 1927.

- Cf. Pashukanis 1924 (repr. 1980). On Soviet legal exceptionalism, see also Tarakouzio 1935.

- For reference, see, for example, Zimmermann 2015: 452‒80.

- Cf. Lieven 1995; Stolleis and Simon 1989; Joerges and Galeigh 2003.

- Beatson and Zimmermann 2004; Palmier 2006; contrast with Koskenniemi 2004. On Raphael Lemkin’s intellectual response to the condition of statelessness, see Moyn 2014; and on Lemkin, see Siegelberg 2013.

- For overviews, see Butler 1980; Bernhard 1984; Bull and Watson 1984; Koskenniemi 2004, 2012; Fassbender 2012; Fassbender, et al. 2012. See also Schiavone 2012; Schulz 2007; and Scobbie 2012.

- For the most recent overview, see Avenarius 2014. For a more historical overview, see Grabar 1901; Martens 1883; Martens 1874‒1909; ‘Das römische Recht in Russland’ (1906); Nippold 1924.

- ESBE sv. ‘Rim’ (Guerrier).

- As defined prominently by the school of von Savigny 1840. See also Maine 1875; Pobedonoscev 1873, 1871, 1880; Sohm 1908; Pokrovsky 1917; Koschaker 1947; Halecki 1957; Lemberg 2000. For recent scholarly perspectives on Roman law, see Johnston 2015.

- ESBE sv. ‘Grazhdanskoe pravo’ (Vladimir Nechaev). The names of exiled civil law experts are Nevolin, Redkin, Kalmykov, Kunitsyn, Krylov and others. See also ESBE sv. ‘Rimskoe pravo’ (Pokrovskii).

- Cf. von Freytag-Loringhoven 1905. Loringhoven had begun his career with an analysis of this special status at Tartu university (then renamed Yur’ev), but eventually fled Russia and had a high-flying career as a publicist in Nazi Germany, where he edited the journals Völkerrecht und Völkerbund and subsequently Europäische Revue. See also Freytag-Loringhoven 1919; Freytag-Loringhoven 1936. For the context of Baltic legal exceptionalism, see Fassbender, et al. 2012, especially Mälksoo 2012b; and Lieven 2006. On National Socialist law, see Stolleis 1989.

- ‘Das römische Recht in Russland’ (1906); von Transehe-Roseneck 1906‒1907. See also Pokrovac 2007; Rudokvas and Kartsov 2007; Kartsov 2007; Luts-Sootak 2007.

- ‘Russia’s proposals for next Peace conference’, 7 April 1914, The Manchester Guardian.For an historical overview, see Mälksoo 2015. See also Taube 1929 and Rybachenok 2005; Roshchin 2017.

- Taube 1894, 1899, 1902. See also the excerpts in Gorovcev 1909.

- For an overview, see Koskenniemi 2012.

- Carr 1939. On crisis and the law, see Joerges and Galeigh 2003.

- Sohm 1908: 52ff. For a new view of Roman law as a source of global law, see Domingo 2010.

- Taube 1930: 291, 295ff. See also discussion in Wehberg 1959; and passim in Kōnstantopoulos and Wehberg 1953.

- Taube 1922; see also discussion in Starodubtsev 2000 and Paramuzova 2008.

- On Taube’s role in the government in exile, see Elenevskaia 1968: 152‒3.

- For more details on this organization, see Kellogg 2005.

- On the end of his career in 1939, and his inconclusive attempts to return to it in 1941, see Steveling 1999: 460, n. 317. For his publications from this period, see Taube 1933; Taube 1935.

- Taube to the Rector of Münster University, 19 December 1937. Cited in Steveling 1999: 368, n. 435.

- On Roerich’s Catholicism, see Elenevskaia 1968: 69.

- Andreyev 2014: 341. See also the letter from Taube to Roerich, 10 August 1932. International Roerich Centre, Moscow, Fond 1. No 8075, pp. 39–40 (http://lib.icr.su/node/1320, seen on 28 August 2017).

- On Taube’s view of Byzantium, see Taube 1939. On the Eurasian connections with the right, see ‘Delegation in Germany’, in Russisches Wissenschaftliches Institut: Various Correspondence, Financial Statements, Press Cuttings, etc., 1922–1932, C1255/151/170.1, UNOG Records and Archives Unit, Nansen Fonds, Refugees Mixed Archival Group, 1919–1947. On the connections between the Russian expatriate uni-versities and the old imperial elites, see the papers of Mikhail Nikolaevich de Giers, the last Russian ambassador in Rome during the First World War. Mikhail de Giers papers, Box 21, Folder 1, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford, California. See also Browder and Kerensky 1961.

- Soloviev 1896; Troubetskoi 1925; Mitteis 1963. On Byzantinism, see Cameron 1992; Marciniak and Smythe 2015.

- For a biography of Taube in his Russian context, see Mälksoo 2015; Mälksoo 2008. For Taube among the white Russians form an archival perspective, see the discussion of the Bakhmeteff archive in Raeff 1990. On the Russian diaspora and its politics, see Fassbender 2012.

- For a good indication of his reputation in later years, see the oblique references to Taube’s political views in Wehberg 1959/1960. For the broader context of central European lawyers’ orientation towards international law, see Sands 2016. See also Lesaffer 2016. See also Fassbender, et al. 2012. For more precise examples, see Grabar 1893; Grabar 1901; Grabar 1912; Grabar 1990; and Lauterpacht 1927.

- Weir 2015. On the Soviet Union as an empire, see Keep 2002.

- Berg 1927. More on Catholicism in the Russian émigré community, see Golovanov 2015. On Russians in interwar Germany, see Casteel 2008.

- For the various debates about longue durée history in Russian imperial discourse, see Etkind 2011. On Catholicism as a minority religion in late imperial and early Soviet Russia, see Solchanyk and Hvat 1990. Taube himself recommended this source for a history of Catholicism in Russia: Tolstoj 1863/1864. For the perspective of the Baltic genealogists, see Dellinghausen 1928; Stackelberg 1930; Stavenhagen 1939.

- Cf. Jellinek 1914: 337. See also Jellinek 1892.

- Taube 1907/1908. On the history of Catholicism in the Cold War, especially in Eastern Europe, see Ramet 1990.

- Scobbie 2012. On the German concept of the subject of international law in the 1930s, see Steck 2003.

- On ideas of Europe in imperial contexts, see Osterhammel 2004.

References

- Andreyev, A. (2014), The Myth of the Masters Revived: The Occult Lives of Nikolai and Elena Roerich, Leiden: Brill.

- Anzilotti, D. (1902), Teoria generale della responsibilitá dello stato nel diritto internazionale, Florence: F. Lumachi.

- Avenarius, M. (2004), Rezeption des römischen Rechts in Russland: Dmitrij Mejer, Nikolaj Djuvernua und Iosif Pokrovskij, Göttingen: Wallstein.

- Avenarius, M. (2014), Fremde Traditionen des römischen Rechts. Einfluß, Wahrnehmung und Argument des »rimskoe pravo« im russischen Zarenreich des 19. Jahrhunderts, Göttingen: Wallstein.

- Beatson, J. and Zimmermann, R., eds. (2004), Jurists Uprooted: German-Speaking Emigré Lawyers in Twentieth Century Britain, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bernhard, R., ed. (1984), Encyclopaedia of Public International Law, North-Holland: Elsevier.

- Browder, R. P. and Kerensky, A., eds. (1961), The Russian Provisional Government 1917 Documents, vol. 1, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Bull, H. and Watson, A., eds. (1984), The Expansion of International Society, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bunce, V. (2000), ‘The Historical Origins of the East-West Divide: Civil Society, Political Science, and Democracy in Europe’, in N. Bermeo and P. Nord (eds), Civil Society before Democracy: Lessons from Nineteenth Century Europe, 209–36, London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Butler, William E., ed. (1980), International Law in Comparative Perspective, Alpen aan den Rijn: Sijthoff.

- van Caenegem, Raoul C. (1991), Legal History: A European Perspective, London: Hambledon.

- Cameron, A. (1992), The Use and Abuse of Byzantium, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carr, E. H. (1939), The Twenty Years’ Crisis: 1919–1939: An Introduction to the Study of International Relations, London: Macmillan.

- Casteel, J. (2008), ‘The Politics of Diaspora: Russian German Émigré Activists in Interwar Germany’, in Matthias Schulz, James M. Skidmore, and David G. John (eds), German Diasporic Experiences: Identity, Migration, and Loss, 117–30, Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- ‘Das römische Recht in Russland’ (1906), in R. Leonhard(ed.), Stimmen des Auslands u ̈ber die Zukunft der Rechtswissenschaft, 105–6, Breslau: M&H Marcus.

- von Dellinghausen, E. (1928), Die Entstehung, Entwicklung und Aufbauende Tätigkeit der Baltischen Ritterschaften, Langensalza: H. Beyer.

- Domingo, R. (2010), The New Global Law, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Elenevskaia, I. (1968), Vospominaniya [Memoirs], Stockholm: no publisher known,Encyclopedicheskiy slovar’ Brokgauza i Efrona [ESBE], 86 vols. (1890‒1907), St. Petersburg and Leipzig: Efron.

- Etkind, A. (2011), Internal Colonization: Russia’s Imperial Experience, Cambridge: Polity.

- Fassbender, B. (2012), ‘Hans Kelsen’, in B. Fassbender, A. Peters, S. Peter and D. Högger (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law, 1167–73, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fassbender, B., Peters, A., Peter, S. and Högger, D., eds. (2012), The Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- von Freytag-Loringhoven, A. (1905), Vstuplenie naslednika v obiazatel’stva i prava trebovania nasledovatelia po ostzeiskomu pravu do kodifikatsii 1864 g., Yur’ev: K. Matthiessen.

- von Freytag-Loringhoven, A. (1919), Russland, Halle: Max Niemeyer.

- von Freytag-Loringhoven, F. (1936), ‘Rechtfertigung des Völkerrechts’, Völkerbund und Völkerrecht, 3: 161–6.

- Golovanov, S. (2015), Russkoe katolicheskoe delo. Rimsko-katolucheskaia tserkov’ i russkaia emigratsia, Omsk: Amfora.

- Gordley, J. (1991), Philosophical Origins of Modern Contract Doctrine, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gorovcev, A. (1909), Mezhdunarodnoe pravo. Izbrannaia literatura. Kratkaia Encyclopedia,St. Petersburg: Trenke and Fusno.

- Grabar, V. (1893), ‘Voina i mezhdunarodno’e pravo’, Uchenye zapiski imperatorskago Iur’evskago universiteta, 4: 23–45.

- Grabar, V. (1901), Rimskoe pravo v istorii mezhdunarodno-pravovykh uchenii: elementy mezhdunarodnogo prava v trudakh legistov XII‒XIII vv. [Roman law in the history of international doctrine: elements of international law in the works of the 12th and 13th-century jurists], Yur’ev: Matthiesen.

- Grabar, V. (1912), Nachalo ravenstva gosudarstv v sovremennom mezhdunarodnom prave, St. Petersburg: Kirschbaum.

- Grabar, V. (1927), ‘Das heutige Völkerrecht vom Standpunkte eines Sowjetjuristen’, Zeitschrift fur Völkerrecht, 9: 188–214.

- Grabar, V. (1990), The History of International Law in Russia, 1647‒1917: A Bio-bibliographical Study, ed. and transl. William E. Butler, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Halecki, O. (1957), Europa. Grenzen und Gliederung seiner Geschichte, Darmstadt: Herman Gertner.Holquist, P. (2006), ‘Dilemmas of a Progressive Administrator. Baron Boris Nolde’, Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History, 7 (2): 241–73.

- Jellinek, G. (1892), System der subjektiven öffentlichen Rechte, Freiburg: Mohr.

- Jellinek, G. (1914), Allgemeine Staatslehre, Berlin: Haering.

- von Ihering, R. (1852, 1854, 1858), Der Geist des römischen Rechts auf den verschiedenen Stufen seiner Entwicklung, 3 vols, Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

- Joerges, C. and Galeigh, N. S., eds. (2003), Darker Legacies of Law in Europe: The Shadow of National Socialism and Fascism over Europe and its Legal Traditions, Oxford: Hart.

- Johnston, D., ed. (2015), The Cambridge Companion to Roman Law, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kartsov, A. (2007), ‘Das Russische Seminar für Römisches Recht an der juristischen Fakultät der Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Berlin’, in Z. Pokrovac (ed.), Juristenausbildung in Osteuropa bis zum Ersten Weltkrieg. Rechtskulturen des modernen Osteuropa. Traditionen und Transfers, 317–53, Frankfurt: Klostermann.

- Keep, John L. H. (2002), A History of the Soviet Union 1945–1991: Last of the Empires, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kellogg, M. (2005), The Russian Roots of Nazism: White Émigrés and the Making of National Socialism 1917–1945, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kōnstantopoulos, Dēmētrios S. and Wehberg, H., eds. (1953), Gegenwartsprobleme des internationalen Rechtes und der Rechtsphilosophie. Festschrift fu ̈r Rudolf Laun fu ̈r seinem siebzigsten Geburtstag, Hamburg: Girardet.

- Koschaker, P. (1947), Europa und das römische Recht, Munich: C. H. Beck.

- Koskenniemi, M. (2001), The Gentle Civilizer of Nations: the Rise and Fall of International Law, 1870‒1960, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Koskenniemi, M. (2004), ‘Hersch Lauterpacht and the Development of International Criminal Law’, Journal of International Criminal Justice, 2: 810–25.

- Koskenniemi, M. (2012), ‘International Law in the World of Ideas’, in J. Crawford, M Koskenniemi and S. Ranganathan (eds),The Cambridge Companion to International Law, 47–64, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Landau, P. (1989), ‘Römisches Recht und Deutsches Gemeinrecht’, in M. Stolleis and D. Simon (eds), Rechtsgeschichte im Nationalsozialismus, 11–24, Tübingen: Mohr.

- Lauterpacht, H. (1927), Private Law Sources and Analogies of International Law: With Special Reference to International Arbitration, London: Longmans, Green and Co. Ltd..

- Lemberg, H., ed. (2000), Grenzen in Ostmitteleuropa im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. Aktuelle Forschungsprobleme, Marburg: Herder-Institut.

- Lenin, V. (1924)‚ ‘O zadachakh Narkomyusta v usloviyakh novoi ekonomichesoi politiki’ (On the tasks of the Narkomyust under the conditions of the New Economic Policy), Letter to Dmitry Kursky (20 February 1922), in A. Fradkin (ed.), V Vserossiiskii s’ezd deiatelei sovetskoi yustitsii. Stenograficheskii otchet, Moscow: Yuridicheskoe izd. Narkomyusta RSFSR.

- Lesaffer, R. (2016), ‘Roman Law and the Intellectual History of International Law’, in A. Orford and F. Hoffmann (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the Theory of International Law, 38–59, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Levy, E. (1929), ‘Westen und Osten in der nachklassischen Entwicklung des römischen Rechts’, Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung, 49: 230–59.

- Lieven, D. (1995), ‘The Russian Empire and the Soviet Union as Imperial Polities’, Journal of Contemporary History, 30: 607–36.

- Lieven, D., ed. (2006), The Cambridge History of Russia. Vol. II: Imperial Russia 1689‒1917, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Luts-Sootak, M. (2007), ‘Der lange Beginn einer geordneten Juristenausbildung an der deutschen Universität zu Dorpat (1802–1893)’, in Z. Pokrovac (ed.), Juristenausbildung in Osteuropa bis zum Ersten Weltkrieg. Rechtskulturen des modernen Osteuropa. Traditionen und Transfers, 357–91, Frankfurt: Klostermann.

- Maine, H. S. (1875), Lectures in the Early History of Institutions, New York: Henry Holt & Co.

- Mälksoo, L. (2008), ‘The History of International Legal Theory in Russia: A Civilizational Dialogue with Europe’, The European Journal of International Law, 19 (1): 211–32.

- Mälksoo, L. (2012a), ‘Encounters “Russia-Europe”’, in B. Fassbender, A. Peters, S. Peter and D. Högger (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law, 764–87, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mälksoo, L. (2012b), ‘Friedrikh von Martens’, in B. Fassbender, A. Peters, S. Peter and D. Högger (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law, 1147–52, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mälksoo, L. (2014), ‘F. F. Martens in His Time’, The European Journal of International Law, 25 (3): 811–29.Mälksoo, L. (2015), Russian Approaches to International Law, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Marciniak, P. and Smythe, Dion C., eds. (2015), The Reception of Byzantium in European Culture since 1500, London: Routledge.

- Martens, F. (1883), Sovremennoe mezhdunarodnoe pravo civilisovannykh narodov, 2 vols [Modern International Law of Civilized Peoples], St. Petersburg: Benke.

- Martens, F. (1874‒1909), Receuils des traités et Conventions Conclus par la Russie avec les puissances étrangères, St. Petersburg: Imprimerie du Ministère de Voies de Communication.

- Mitteis, L. (1963), Reichsrecht und Volksrecht in den östlichen Provinzen des Römischen Kaiserreichs: Mit beiträgen zur Kenntniss des griechischen Rechts und der spätrömischen Rechtsentwicklung, Hildesheim: Olms.

- Moyn, S. (2014), Human Rights and the Uses of History, New York: Verso.

- Nippold, O. (1924), ‘“Les conférences de La Haye et la Société des Nations’”. Le développement historique du droit international depuis le Congrès de Vienne’, in Hague Academy of International Law (ed.), Collected Courses of The Hague Academy of International Law, vol. 2, 1–99, The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

- Osterhammel, J. (2004), ‘Europamodelle und imperiale Kontexte’, Journal of Modern European History, 2: 157–81.

- Palmier, J.-M. (2006), Weimar in Exile: The Antifascist Emigration in Europe and America, London: Verso.

- Paquet, A. (1923), Rom oder Moskau, Berlin: Drei Masken.

- Paramuzova, O. (2008), ‘Sovremennye tendencii recepcii rimskogo prava v svete reshenia problem konceptual’nogo pereosmyslenia mezhdunarodno-pravovoi nauki’, Vestnik Sankt-Peterburgskogo Universiteta, 6 (3): 152–67.

- Pashukanis, E. (1924), General Theory of Law and Marxism Obshchaia teoriia prava i marksizm: Opyt kritiki osnovnykh iuridicheskikh poniatii, reprinted in Evgeny Pashukanis (1980), Selected Writings on Marxism and Law, ed. Piers Beirne and Robert Sharlet, 32–131, London: Academic Press.

- Pobedonoscev, K. (1873, 1871, 1880), Kurs grazhdanskogo prava, 3 vols [Course in civil law], St. Petersburg: V. I. Golovine.

- Pokrovac, Z., ed. (2007), Juristenausbildung in Osteuropa bis zum Ersten Weltkrieg. Rechtskulturen des modernen Osteuropa. Traditionen und Transfers, Frankfurt: Klostermann.

- Pokrovsky, I. (1917), Istoria rimskogo prava [History of Roman Law], 3rd edn, Petrograd: Pravo.

- Rudokvas, Anton D. and Kartsov, A. (2007), ‘Der Rechtsunterricht und die juristische Ausbildung im kaiserlichen Russland’, in Zoran Pokrovac (ed.), Juristenausbildung in Osteuropa bis zum Ersten Weltkrieg. Rechtskulturen des modernen Osteuropa. Traditionen und Transfers, 273–317, Frankfurt: Klostermann.‘Russia’s proposals for next Peace conference’, 7 April 1914, The Manchester Guardian.

- Raeff, M. (1990), Russia Abroad: A Cultural History of the Russian Emigration, 1919‒1939, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Rainer, J. M. (2012), Das römische Recht in Europa: von Justinian zum BGB, Vienna: Manz.

- Ramet, P., ed. (1990), Catholicism and Politics in Communist Societies, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Roshchin, E. (2017), ‘The Hague Conferences and “International Community”: A Politics of Conceptual Innovation’, Review of International Studies, 43 (1): 177–98.

- Rybachenok, I. (2005), Rossiya i Pervaya konferenciya mira 1899 v Gaage, Moscow: Institut rossiiskoi istorii.

- Sands, P. (2016), EastWest Street. On the Origins of “Genocide” and “Crimes Against Humanity”, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Savigny, F. C. von (1840), System des heutigen Römischen Rechts, 3 vols, Berlin: Veit und Comp.

- Schiavone, A. (2012), The Invention of Law in the West, trans. J. Carden and A. Shugaar, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

- Schulz, M. (2007), ‘Vom Direktorialsystem zum Multilateralismus: Die Haager Friedenskonferenz von 1907 in der Entwicklung des internationalen Staatensystems bis zum Ersten Weltkrieg’, Die Friedens-Warte, 82 (4): 31–50.

- Scobbie, I. (2012), ‘Hersch Lauterpacht’, in B. Fassbender, A. Peters, S. Peter and D. Högger (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law, 1179–85, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Siegelberg, Mira L. (2013), ‘Unofficial Men, Efficient Civil Servants: Raphael Lemkin in the History of International Law’, Journal of Genocide Research, 15 (3): 297–316.

- Solchanyk, R. and Hvat, I. (1990), ‘The Catholic Church in the Soviet Union’, in P. Ramet (ed.), Catholicism and Politics in Communist Societies, 49–93, Durham, NH: Duke University Press.

- Sohm, R. (1908), Institutionen. Ein Lehrbuch der Geschichte und des Systems des römischen Privatrechts, 13th edn, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot.Soloviev, V. (1896), Vizantizm I Rossia.

- Stackelberg, O. M. von (1930), Genealogisches Handbuch Der Estländischen Ritterschaft, Görlitz: Verl. für Sippenforschung und Wappenkunde Starke.Starodubtsev, G. (2000), Mezhdunarodno-pravovaya nauka rossiiskoi emigratsii (1918–1939), Moscow: Kniga i biznes.

- Stavenhagen, O. (1939), Genealogisches Handbuch der Kurländischen Ritterschaft, Görlitz: Verl. für Sippenforschung und Wappenkunde Starke.

- Steck, Peter K. (2003), Zwischen Volk und Staat. Das Völkerrechtssubjekt in der deutschen Völkerrechtslehre (1933‒1941), Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Steveling, L. (1999), Juristen in Mu ̈nster: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Rechts- und Staatswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität Munster, Münster: LIT-Verlag.

- Stolleis, M. (1989), ‘Introduction’, in M. Stolleis and D. Simon (eds), Rechtsgeschichte im Nationalsozialismus, 1–11, Tübingen: Mohr.

- Stolleis, M. and Simon, D., eds. (1989), Rechtsgeschichte im Nationalsozialismus, Tübingen: Mohr.Tarakouzio, T. (1935), The Soviet Union and International Law, New York: Macmillan.

- von Taube, M. (1894, 1899, 1902), Istoria zarozhdenia sovremennogo mezhdunarodnogo prava, 3 vols [The history of the genesis of modern international law], St. Petersburg: P.I. Schmidt.

- von Taube, M. (1905), Khristianstvo I mezhdunarodnyi mir, 2nd edn, Moscow: Posrednik.

- von Taube, M. (1907/1908), ‘La situation internationale actuelle du Pape et l’idée d’un “droit entre pouvoirs” (jus interpotestates)’, Archiv fur Rechts- und Wirtschaftsphilosophie, 1 (3): 360–8; and no. 4 (1907/08): 510–18.

- von Taube, M. (1915), ‘Istoricheskie korni tepereshnei voinny v epokhu imperatorov Aleksandra i Nikolaia I’, in A. Shemansky (ed.), Istoria Velikoi Voiny, vol. 1, 20–60, Moscow: Vasil’yev.

- von Taube, M. (1922), Vechnyi mir ili vechnaia voina? Mysli o Ligi Natsii, rev. edn, Berlin: Detinets.von Taube, M. (1926a), ‘Études sur le développement historique du droit international dans l’Europe orientale’, Collected Courses of The Hague Academy of International Law, 11 (1): 341–525.

- von Taube, M. (1926b), La Russie et l’Europe Occidentale à travers dix siècles, in Etudes d’histoire internationale et de psychologie ethnique, Bruxelles: La Lecture au Foyer, Librairie Albert Dewit.

- von Taube, M. (1927), ‘Rom und Rußland m der vormongolischen Zeit, Kap. V: Altrußlands religiöse Verbindungen mit der katholischen Welt in der vortatarischen Periode’, in L. Berg (ed.), ‘Ex Oriente’. Religiöse und philosophische Probleme des Ostens und des Westens- Beiträge orthodoxer, unierter und katholischer Schriftsteller in russischer, französischer und deutscher Sprache, Mainz: Matthias Grünewald. Russian text available at http://www.unavoce.ru/library/taube_premongol.html, accessed 13 January 2017.

- von Taube, M. (1928), Rußland und Westeuropa: Rußlands historische Sonderentwicklung in der europäischen Völkergemeinschaft, Berlin: Georg Stilke.

- von Taube, M. (1929), Der Großen Katastrophe Entgegen. Die russische Politik der Vorkriegszeit und das Ende des Zarenreiches (1904‒1917), Berlin: Neuner.

- von Taube, M. (1930), ‘L’inviolabilité des traités’, Collected Courses of The Hague Academy of International Law, 32: 295–389.

- de Taube, M. (1933), Les origines de l’arbitrage international. Antiquité et Moyen Age, Paris: Sirey.

- von Taube, M. (1935), ‘Le statut juridique de la mer Baltique jusqu’au début du xixe siècle’, Collected Courses of The Hague Academy of International Law, 53: 462.

- von Taube M. (1936), Agrafa. O nezapisannykh v Evangelii Izrecheniakh Iisusa Khrista, Warsaw: Biblioteka bratstva pravoslavnykh bogoslovov v Pol’she.

- von Taube, M. (1938), ‘Internationale und Kirchenpolitische Wandlungen im Ostbaltikum und Russland zuz Zeit der deutschen Eroberung Livlands (12. und 13. Jahrhundert)’, Jahrbu ̈cher fur Geschichte Osteuropas, 3 (1): 11–46.

- von Taube M. (1939), ‘De l’apport de Byzance au développement du droit international occidental’, Collected Courses of The Hague Academy of International Law, 67: 233–9.von Taube, M. (2007), ‘Zarnitsy’. Vospominaniya o tragicheskoi sud’be predrevoliutsionnoi Rossii, Moscow: ROSSPEN.

- Tolstoj, Comte D. A. (1863/1864), Le Catholicisme romain en Russie, Paris: Dentu.

- von Transehe-Roseneck, A. (1906), Die lettische Revolution, with an Introduction by Theodor Schiemann, vol. 1, Berlin: G. Reimer (vol. 2, Berlin: G. Reimer, 1907).

- Troubetskoi, N. (1925), ‘Evraziistvo I beloe dvizhenie’, in Trobetskoi, N (2015), Sbornik Rabot (Moscow: Direkt-Media), 5–26.

- Vinogradoff, P. (1929), Roman Law in Medieval Europe, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Wehberg, H. (1931), ‘Review of La Politique russe d’avant guerre et la Fin de l’Empire des Tsars(1904—1917) by Baron M. de Taube’, Die Friedens-Warte, 31 (5): 159–60.

- Wehberg, H. (1959), ‘Pacta Sunt Servanda’, The American Journal of International Law, 53 (4): 775–86.

- Wehberg, H. (1959/1960), ‘Zum 90. Geburtstag von Prof. Michael v. Taube’, Die Friedens-Warte, 55: 56–8.

- Weir, T. (2015), ‘A European Culture War in the Twentieth Century? Anti-Catholicism and Anti-Bolshevism between Moscow, Berlin, and the Vatican 1922 to 1933’, Journal of Religious History, 39 (2): 280–306.

- Wiederkehr, S. (2007), Die eurasische Bewegung. Wissenschaft und Politik in der russischen Emigration der Zwischenkriegszeit und im postsowjetischen Russland, Cologne: Beiträge zur Geschichte Osteuropas.

- Zimmermann, R. (2015), ‘Roman Law in the Modern World’, in D. Johnston (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Roman Law, 452–80, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chapter 5 (93-112) from Roman Law and the Idea of Europe, edited by Kaius Tuori and Heta Björklund (Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2019), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 license.