Exploring the origins, development, and growth of the American empire.

Introduction

The United States is no stranger to strange lands. From its founding as a British colony to its settlement of the West, America is rooted in a tradition of exploration, conquest, and opportunism. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries marked a new era in American expansion. A growing US economy was hungry for more resources and new markets. Politicians pressured the government to protect and promote American interests worldwide. An expanding population was redefining American society. Each of these factors contributed to the age of American imperialism—an era of unprecedented territorial and political growth and cultural development. Following the Spanish-American War of 1898, the US emerged as a formidable world power with territories across the Pacific and Caribbean. Of course, these new borders came with growing pains. As US imperialists insisted that the country had a responsibility to civilize “inferior” peoples, opponents lobbied on behalf of the colonies, insisting that imperialism contradicted the nation’s founding principles of sovereignty, equality, and democracy.

This essay explores the origins, development, and eventual fall of the American empire. An empire is more than a story of geographic borders and international politics; it is also rooted in forces of national pride, popular culture, and indigenous communities. Moving through the colonial settlements of Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, these stories investigate the lives and legacies of citizens and subjects—those who established and defined the American presence abroad; those who fought to keep the American flag off their soil; those who crafted domestic visions of exotic lands; and those who negotiated life in the empire. This exhibition maps the diverse and rocky terrain of the American empire to show how it informs contemporary conversations on heritage, citizenship, racism, and globalization.

The Age of Imperialism

Overview

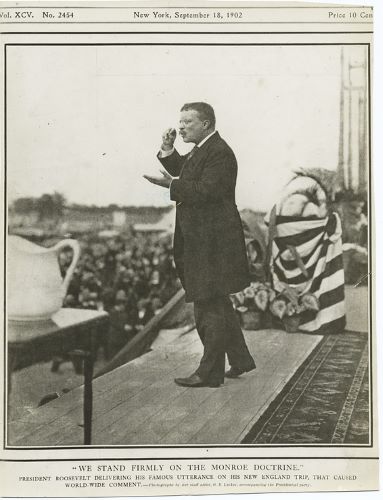

During his farewell address in 1796 President George Washington warned the young republic to “steer clear of permanent alliances with…the foreign world.” Fast forward to 1823—President James Monroe stood before Congress and issued the Monroe Doctrine which advocated extending the nation’s reach through the Americas to safeguard national security. “We should consider any [foreign] attempt… to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere,” Monroe declared, “as dangerous to our peace and safety.”

The Monroe Doctrine inspired a new period in US foreign policy. From the annexation of Texas in 1845 to the Mexican American War of 1846 to 1848, the US aggressively pursued new lands in the name of national interests. America’s reign as an imperial force, however, did not begin until 1898 with the Spanish-American War. What began as a mission to liberate Cuba from Spanish rule—and in the process, rid the US of the threat of European invasion—grew into an international war that left the victorious US bigger and richer than when it had started.

This section examines how the age of imperialism began in America as political and economic agendas underpinned campaigns to defend the US. These are the stories of what, as one newspaper reported, “put the taste of Empire in the mouth of the people.”

Instigating an Empire

The late nineteenth century was a time of crisis and confidence in the US. A financial panic left industries in search of new markets to sell their goods, particularly in Asia and Latin America. Meanwhile, as immigration rates to the US soared, a wave of nationalism inspired citizens to define what it meant to be an American. For example, the 1890s saw the creation of patriotic traditions like the Pledge of Allegiance. Others thought more strategically. Captain Alfred Mahan Thayer published The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, which argued for the US to invest in its navy and take control of international waters.

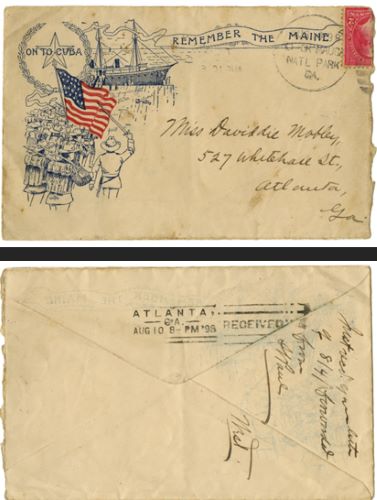

On February 15, 1898, the USS Maine, an American naval ship, exploded in Havana, Cuba leaving 262 American soldiers dead. Although an official investigation named no perpetrator, newspapers quickly blamed Spain. The “yellow press,” sensational journalism that relied more on fabrication than fact, transformed the USS Maine into a national spectacle as reporters circulated dramatic accounts of the explosion and made allegations about Spain’s involvement in the attack. “Remember the Maine!” became an inescapable cry. Americans demanded retribution.

Vengeful public sentiment mixed with economic interests and rising nationalism compelled the US to take action against Spain. As one man recalled, “Whenever the battleship Maine is mentioned, my memory leaps…to the excitement aroused by the word ‘war.'”

The Splendid Little War

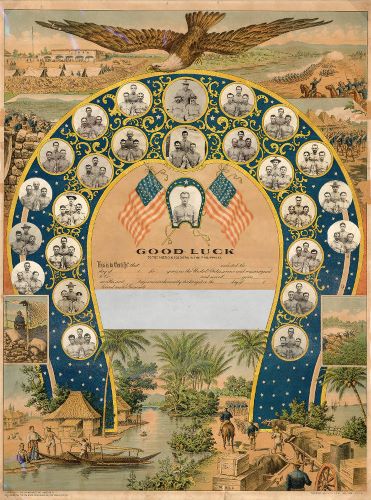

After weeks of public outcry and political debate, the US declared war on Spain on April 25, 1898. Troops set out for Cuba intent on freeing the island from Spanish rule. The US also sought to liberate Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines in order to target—and eventually destroy—Spain’s global empire. African Americans enlisted, seeing the war as an opportunity to secure greater rights and freedoms in the US by proving their strength and loyalty overseas. Cuban and Filipino soldiers eager for independence also fought alongside American soldiers.

Back home, the war captivated the public. Hundreds took part in battle re-enactments and watched war films. In Omaha, Nebraska, more than one million people gathered to watch a replica of the USS Maine explode at the city’s world’s fair. Continuing the trend of the “yellow press,” newspapers entertained readers daily with stories and images from the front lines.

Secretary of State John Hay described the Spanish-American War as the “splendid little war.” It was brief, lasting only a few months, and relatively bloodless, as the US lost more men to disease than in combat. With aggressive campaigns over land and sea, the US defeated Spanish forces in Cuba and cornered them in Puerto Rico and the Philippines. By July, Spain sued for peace.

Peace and Power

The Spanish-American War was over almost as quickly as it started.

In November 1898, the US and Spain met in Paris to draft a treaty. Initially the US stood firm in its commitment to independence. Congress went so far as to add the Teller Amendment to the war declaration to prohibit the annexation of Cuba. Peace negotiations, however, revealed the US’s more opportunistic, more imperialistic agenda. The Treaty of Paris granted independence to Cuba and forced Spain to cede Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines to the US.

The war also established the policies and players of America’s growing empire. Most notably Theodore Roosevelt became a national hero. Memoirs, silent films, and traveling shows celebrated how he and his Rough Riders, a volunteer cavalry regiment, fought through Cuba. Roosevelt channeled this celebrity and bravado into his political career. As president, he “walked softly and carried a big stick,” aggressively defending American territory and policy. He assured critics: “so long as a nation shows that it knows how to act with decency… it need fear no interference from the United States.” Still, he and his supporters pressed on to make the “United States the dominant power on the shores of the Pacific Ocean.”

The age of imperialism had begun.

Building the Empire

Overview

Running an empire demanded more than a treaty. The US labored for decades before and after the Spanish-American War to lay the groundwork and administrative systems that supported its new borders. This section explores how America officially annexed Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Hawaii.

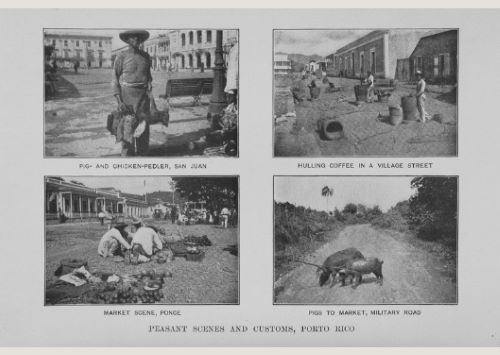

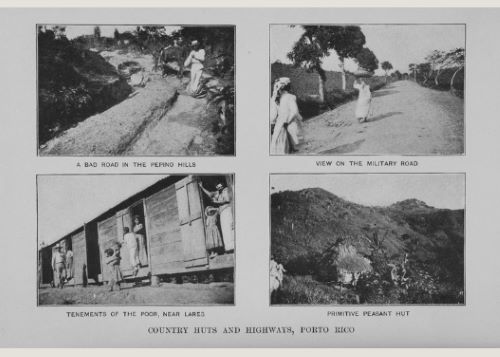

Beginning in the fifteenth century, Puerto Rico was a stronghold of Spain’s Caribbean empire. With the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, the US quickly set its sights on San Juan. American troops invaded and occupied Puerto Rico in July 1898 and met little resistance. Puerto Ricans welcomed the US as a liberator. They interpreted American collaboration as a chance for economic reform and eventual freedom. By October, Spain surrendered Puerto Rico to American troops, yet with peace came new tension. Puerto Ricans lobbied for independence. Politicians in Washington, DC questioned where exactly Puerto Rico—and the other new territories—stood in relation to mainland politics.

Debate came to a head with a series of Supreme Court rulings known as the “insular cases.” These determined that the Constitutional rights allotted to states and citizens did not apply to Puerto Rico or its people, even though the territory was subject to taxes, legislation, and other obligations dictated by Congress. According to the Supreme Court, Puerto Rico would be “foreign in a domestic sense.”

The Philippine-American War

The Philippines waged a fiery, but ultimately unsuccessful, war against American imperialists.

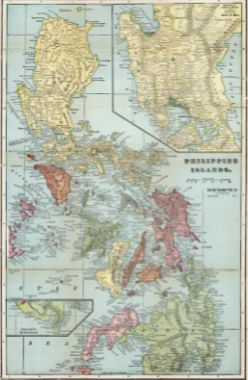

Revolution had been brewing in the Philippines long before the Spanish-American War. In 1896, Filipino nationalists, largely organized by the militant Katipunan group, waged an armed rebellion against Spain. Emilio Aguinaldo, leader of a Katipunan faction, emerged as prominent military and political leader. The resistance even established the First Republic of the Philippines with Aguinaldo at its head. Neither Spain nor the US recognized its legitimacy. Nonetheless, during the Spanish-American War, Filipinos fought alongside the US hoping that an American alliance and victory would mean independence. Allies, however, soon became enemies.

In the Treaty of Paris, the US agreed to annex the Philippines at the cost of $20 million. Angered by the betrayal, Filipinos declared war. The Philippine-American War was a bloodier and more brutal affair than its predecessor. Where the US won in manpower and technology, Filipino rebels made up for their military deficit with tenacious guerrilla tactics. Philippine General Elwell S. Otis promised to “drive the Americans into the sea.” By 1902 the US had captured Aguinaldo and devastated a majority of Filipino cities and communities. The war came to an end, and President Theodore Roosevelt pardoned the insurgents. The Philippines was now officially a US territory.

America Takes Hawai’i

The US planted its flag in Hawaii well before 1898. With the help of Christian missionaries and sugarcane planters, Americans settled in Hawaii forming a robust, wealthy—and largely white—class who lobbied for the US. Their ambitions came to a head in 1887 with the Bayonet Constitution. Issued by a coalition of American and European industrialists and Hawaiian elite, the document aimed to dismantle the Hawaiian monarchy by transferring legislative and executive power to the US and stripping native Hawaiians and Asian immigrants of their citizenship rights. President Grover Cleveland rejected the document stating that it constituted nothing less than an “armed invasion… committed…without the authority of Congress.”

Native Hawaiians fought back by drafting their own document to “maintain…the independent autonomy of the islands of Hawaii…[and] secure…the continuance of their civil rights.” Queen Liliuokalani, sister to King Kalakaua, also moved to restore power to the monarchy and native Hawaiians, but she was eventually deposed in 1893 during a coup d’etat organized by the US. Increasing interests in Pacific trade and industry, coupled with the strategic advantage Hawaii provided during the Spanish-American War, compelled President McKinley to formally annex the islands in July 1898. In August, the US celebrated the transfer of power with a ceremonial flag raising over Iolani Palace in Honolulu.

American Subjects or Citizens?

Overview

American imperialism involved more than the politicians, soldiers, businesses, and patriots who designed the empire in their favor. US imperial policies posed deeper questions about the concept of the citizen.

How far did the Constitution follow the flag?

For the millions of men and women in Puerto Rico, Hawaii, and the Philippines who suddenly found themselves living on American soil, one question prevailed: What new opportunities did life in America’s empire allow? This section investigates how Hawaiians, Puerto Ricans, and Filipinos staked their claim in the American empire. They did not enjoy the full rights and privileges allotted to American citizens. Nevertheless, these individuals navigated courses across the Pacific and Caribbean in search of agency and opportunity. The stories featured here are exceptional, representing the lives of the privileged few. Taken together, however, they reveal how native peoples fashioned themselves as American citizens.

Civil Service

The US relied on the obedience, cooperation, and expertise of the people of their new territories to establish order across the Pacific and Caribbean. When the US invaded Puerto Rico, they turned to local scouts to help with the military campaign against the Spanish. Once Spain surrendered, the US rewarded its collaborators, not with independence, but with employment in the territorial government. These appointees were familiar with Puerto Rican traditions and loyal to American interests and facilitated the transfer of power from Spain to the US.

President McKinley appointed a number of American officials to top positions in the colonial government. Before assuming the presidency or presiding as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, William Howard Taft served as the first US governor of the Philippines. In this role he defined a “policy of attraction” in the Philippines. Most Americans governed alongside native Filipinos, as Taft had imported the concept of American bureaucracy which created thousands of empty jobs to be filled. It is important to note that the Filipinos who staffed the colonial bureaucracy did not represent the whole population. Most were members of an elite, wealthy, and educated class who largely benefited from American rule.

Civil service provided individuals across the empire a chance for self-determination, even as the status of citizen or independence was denied to them.

Moving across Borders

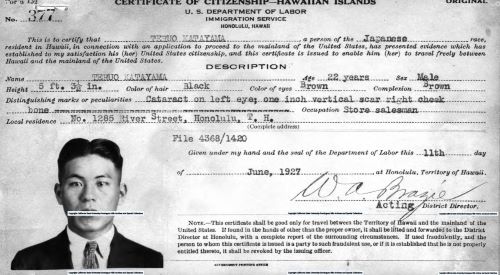

With their land now part of the US, the people of Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines found borders more permeable. Just as intrepid Americans travelled across the territories in search of new adventures, natives and long-time residents began moving to the mainland.

Hawaii was an especially popular hub for in-migration during American imperialism. The islands had a distinct and diverse population, thanks in large part to the sugar industry. Demand for the sweetener skyrocketed during the Civil War, prompting plantation owners to actively recruit laborers from Asia. When the US annexed the islands in 1898, it bestowed national status to native Hawaiians, Filipinos, Japanese, Koreans, and Chinese. Many moved West. For Chinese workers, this was especially beneficial, as the Chinese Exclusion Act passed a few years prior in 1882 barred Chinese immigrants from outside the US. Hawaiian-born, or at the very least naturalized, Chinese could negotiate entry. Puerto Rico similarly provided a new channel to the US from the Caribbean. In 1910, less than 2,000 Puerto Ricans lived on the mainland; by the 1930s, more than 40,000 Puerto Ricans had migrated, and most lived in New York City.

Imperial borders provided a new, if not heavily regulated, space for peoples across the Pacific and Caribbean to imagine and pursue new lives as Americans.

Colonization

Overview

From the Mayflower pilgrims to western pioneers, the US perfected the art of colonialism. This era of American imperialism distinguished itself because the nation labored to keep its new lands at a distance. This section explores the divisions between American citizens and subjects. How did the US employ, “civilize,” educate, and control the peoples of Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines? How did they fight back?

Much of America’s control began on the ground with farms and labor. In Hawaii, for example, the US created so-called sugar societies—regions dominated by American plantations whose hold over farmland and sugar exports provided influence over local politics. Most sugar society elites were the descendants of missionaries and farmers who arrived decades earlier. Following annexation, Puerto Rico was similarly transformed into a hub for sugar and coffee farms with elite planters dictating the island’s policies with the US. Trade also favored the mainland. High tariffs supported American businesses exporting manufactured items to the Pacific and Caribbean and kept industries in Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines at a competitive disadvantage. With these economic systems in place, the colonies could not be seen as American. As noted by the Boston Herald: “we can never make…of the islands what we have made of Louisiana and California, states have an equal right.”

The White Man’s Burden

For some, America’s empire was less a matter of money and more a matter of charity. Hawaiian missionaries constituted one of the earliest waves of American settlement in the Pacific. Reflecting on his arrival in Hawaii, Rev. Hiram Bingham wrote: “The appearance of destitution, degradation, and barbarism…was appalling. Can these be human beings?” Bingham, his congregation, and many after him stayed because they believed their duty as Christian citizens was to civilize the Hawaiian people.

Others heralded the American empire as a “new day of freedom”—a time of order, morals, and growth for all annexed territories. President McKinley himself described his policies as a means for “benevolent assimilation.” New borders would promote stability and prosperity for the colonizer and colonized. Perhaps most memorably, author Rudyard Kipling coined the term “white man’s burden.” Writing on the Philippine-American War, Kipling outlined the responsibility the US, Europe, and greater West had to the rest of the world. As international leaders in politics, technology, values, and culture, they had to better the lives of less developed, non-white peoples. But time and again, the weight of this burden proved that charity was a means for control.

Colonial Education

Schoolhouses provided a space for Americans and native peoples to come together, albeit on uneven ground. In Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, students gathered, and the relationships between them and their teachers mirrored the power dynamics between the colonized and colonizer.

Following the annexation of Puerto Rico, the US reopened the island’s schools with American educators. The US also prioritized public education in the Philippines. Government policy allocated nearly half of its annual budget to schooling, and official legislatures dictated curricula. Teachers taught almost exclusively in English, and they modeled their problem sets, student exercises, and class rules after American traditions. William B. Freer taught in the Philippines from 1901 to 1904. A native of Akron, Ohio, he worked under a contract with the US government and instructed classrooms in villages on the island of Luzon. He documented this work with writings and photographs that he later published as a memoir. Reflecting on his time overseas, Freer framed education as a colonial endeavor. He helped mold students into good subjects, familiar with and loyal to the US. Freer himself concluded: “In such absence of enlightened sentiment…what genuine well-wisher of the Filipinos will desire to allow them… their independence…to place the responsibility of the ignorant many in the hands of the educated few?”

The Territories Fight Back

The people of Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines did not simply assimilate into America’s new empire. Despite growing restraints on their rights, opportunities, and privileges, individuals found ways to resist the US before and after annexation.

Relentless Filipino insurgents challenged American troops through the Philippine-American War. While they ultimately lost the fight, and by association their land, Filipino patriots effectively convinced the US to rule more leniently over the Philippines. Native Hawaiians creatively protested the imposition of American political and cultural order. By the 1830s, US missionaries successfully lobbied the monarchy to ban the practice of hula. In the conservative eyes of the church, the indigenous dance was a symbol of heathen religion and sensual pleasure. Native Hawaiians, however, persisted. They not only performed the hula, but also taught the steps to younger children. With the native flag removed from the Iolani Palace, women sewed it into quilts. Language also became a powerful means of resistance. Villages memorized and performed Hawaiian epics like the Ka mo’olelo of Hi’iakaikapoliopele. Newspapers, once a popular tool for American industrialists and missionaries, now gave voice to those speaking against the US. Ka Hoku o Ka Pakipika was printed exclusively in native Hawaiian, and their stories covered issues such as the decline of native populations and water disputes with plantations.

America’s Empire at Home

Overview

Thousands of miles separated the US from its colonies. This did not stop Americans from imagining Hawaii, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico. They were far-away and exotic, the source of constant curiosity and excitement. Still, they were familiar, inspiring American fashion and entertainment. This section explores how American popular culture—from world’s fairs to wallpaper, prose to politics—brought the nation’s empire into the lives of average Americans.

Seattle, Washington held one of the largest celebrations of America’s newfound international influence. Since the late 1890s, the city had been the gateway to Alaska serving as a major outpost for explorers and entrepreneurs headed north. The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition opened in 1909 to celebrate the city and nation’s connections with Alaska, Canada, and the Pacific Rim.

Among the carnival rides, souvenir stands, and ornate gardens stood a number of other, more exotic exhibitions—models of Hawaiian villages, copies of treaties with Puerto Rico, and Alaskan dog sleds. On the exposition’s Pay Streak boardwalk, organizers installed a Filipino Igorotte village with fifty native peoples brought in from the Philippines. Attendees had to pay an extra fifty cents for all human exhibitions, but many purchased the ticket. With it, they could watch indigenous peoples like the Igorrote live on the boardwalk. They cooked, slept, sang, and danced, all to the delight and unrelenting demand of exposition-goers.

Imperial Interiors

As the nation expanded, its international profile rose and American women strove for a more cosmopolitan aesthetic. A decorating manual from 1913 associated women with the homes they kept. It claimed: “We are sure to judge a woman…by her surroundings. We judge her temperament, her habits, her inclinations, by the interior of her home.” Elite women staged the world in their homes. Wallpapers depicted scenes from the Philippines so that families could peer into the Pacific from the comfort of their drawing room. The pineapple became a symbol for wealth and charm; only the most gracious (and incidentally, wealthiest) hosts welcomed guests with Hawaii’s trademark fruit. Meanwhile, Americans overseas held tight to traditional fashion and design from home. In the Philippines, for example, westernized spaces provided familiar comforts in new lands, as well as a model of civility for native peoples.

US obsession with imperial imagery was controversial. The trend was based almost entirely on orientalist stereotypes—how the West chose to imagine the East. The thought of women as imperial homemakers also perpetuated the thought that a women’s only place was in the home. For all its imagination, American popular culture ultimately kept the reality of empire, its lands, peoples, and politics, at bay.

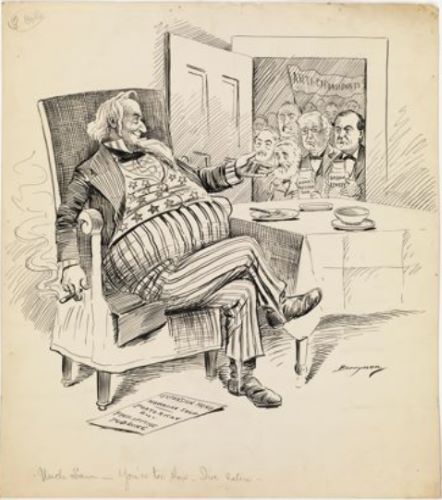

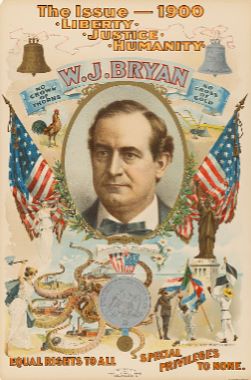

The Anti-Imperialist Movement

Not all Americans were excited by the expansion of the nation’s empire. Anti-imperialists protested the nation’s growing interest in foreign territories. William Jennings Bryan became one of the movement’s most prominent leaders and ran for president on an anti-imperialist platform in 1900. Bryan lost the election, but the anti-imperialist movement carried on. It was a broad coalition uniting citizens across race, class, gender, and political party lines. While these groups worked to a common goal—an end to aggressive American expansion—their motivations often varied.

Some anti-imperialists supported segregation in addition to self-determination. They argued that the US should remain within its borders to avoid the mixing of white and nonwhite peoples. Others perceived empire as a direct contradiction to the nation’s democratic commitments. Writing on the Philippine Islands, one man commented: “If the Declaration of Independence be true…[Filipinos] are to decide for themselves…otherwise there is no freedom.” African American anti-imperialists like W. E. B. Du Bois found disturbing similarities between the racist Jim Crow policies of the American South and colonial oppressions dictating the lives of native Hawaiians, Filipinos, and Puerto Ricans. The anti-imperialist movement was but another front for Black activists to combat racism.

The End of the Empire

Overview

America’s empire unraveled after World War II. The war was a devastating conflict leaving countries in ruins and millions dead. At the same time, the aftermath of World War II reignited campaigns for independence across colonies. This section follows how Hawaii, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico renegotiated their relationships with the US. From the Pacific to the Caribbean, the legacies of America’s empire continued to shape foreign and domestic policy and popular culture.

For Hawaii, the American flag stayed in place. In August 1959, President Eisenhower officially declared Hawaii the fiftieth state. This followed months of debate both on the islands and in the mainland. To determine its fate, the Hawaiian government polled residents in 1950 and 1959, and they overwhelmingly approved both a state constitution and the larger statehood bill. Territorial representative John Burns embarked on an ambitious campaign through Washington DC to rally support for Hawaiian statehood. Meanwhile in Congress, the statehood bill became involved with other national issues. Southern Democrats, as an example, opposed Hawaii because they thought the admission would tip the civil rights debate against them. Nevertheless, Hawaii was added to the union and earned a star on the flag. In 1993, President Bill Clinton issued an official apology for the US’s involvement in overthrowing the Hawaiian monarchy.

A New Independence

The foundation of Philippine independence took root early in the twentieth century. Despite the defeat of Filipino patriots and continued challenges from scattered rebel groups, the Philippines enjoyed a measure of self-rule under the US. In 1912, President Woodrow Wilson replaced the Philippine Commission, largely staffed by presidential appointments, with the democratically elected Philippine Senate. By 1935, the US recognized the formation of the Philippine Commonwealth, headed by President Manuel L. Quezon. Both Manila and Washington, DC imagined the commonwealth as the organization that would help the archipelago transition from American territory to sovereign nation.

All negotiations ended with World War II.

The Japanese invaded the Philippines in 1942 and occupied the islands through 1945. President Franklin Roosevelt’s initial reluctance to send troops to the islands was controversial, but the Philippines ultimately played a key role in America’s Pacific campaign. With the war’s end came liberation. In 1946, US officials returned to the Philippines and ratified the Treaty of Manila. This granted full independence to the Philippines, as well as guaranteed war reparations and trade concessions. Manuel Roxas was elected the first president. On July 4, 1946, crowds gathered in the streets of Manila to celebrate. The republic was now free from Spain and the US.

Controversy over Commonwealth

Since its annexation in 1898, Puerto Rico has challenged America’s imperial legacy. In 1916, Resident Commissioner Luis Muñoz Rivera demanded: “Give us the field of experiment…that we may show it is easy for us to constitute a stable republic government…give us our independence and [America] will stand…a great liberator of oppressed peoples.”

In spite of this resistance, the island has remained a US commonwealth since 1952. Puerto Ricans have the power to vote for their governor and executive council but, due their nation’s legal status, lack many of the same rights allotted to other US citizens. Puerto Ricans cannot vote for president, though they may be drafted. They have no voting representative in Congress, yet are still taxed under US law. Debate continues: statehood, independence, commonwealth? The government held plebiscites—public polls on Puerto Rico’s federal status—in 1967, 1991, 1993, and 1998. In 2012, President Barack Obama, approved yet another plebiscite, with 61 percent of Puerto Ricans favoring statehood in light of enduring economic troubles. Those in Congress, however, fear the labor of restructuring the House, Senate, and even the flag, around a fifty-first state. For now, Puerto Rico remains at the edges of the union and on the cusp of sovereignty.

Resources

- Kaplan, Amy. The Anarchy of Empire in the Making of U.S. Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Kaplan, Amy, and Donald E Pease. Cultures of United States Imperialism. Durham: Duke University Press, 1993.

- Miller, Bonnie M. From Liberation to Conquest: The Visual and Popular Cultures of the Spanish American War of 1898. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011.

- Ninkovich, Frank. The United States and Imperialism. Malden: Blackwell Publishers, 2001.

- Seymour, Richard. American Insurgents: A Brief History of American Anti-imperialism. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012.

- Silva, Noenoe K. Aloha Betrayed: Native Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. Haunted by Empire: Geographies of Intimacy in North American History. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

- Wagenheim, Olga Jiménez de. Puerto Rico: An Interpretive History from pre-Colombian times to 1900. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 1998.

This exhibition was curated by Andrea Ledesma, MA in Public Humanities at Brown University, with materials contributed by California Digital Library, David Rumsey, Digital Commonwealth, Digital Library of Georgia, Digital Library of Tennessee, Empire State Digital Network, HathiTrust, Illinois Digital Heritage Hub, Mountain West Digital Library, National Archives and Records Administration, The New York Public Library, PA Digital, The Portal to Texas History, Recollection Wisconsin, Smithsonian Institution, South Carolina Digital Library, University of Southern California Libraries, and University of Washington.

Published by the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), May 2017, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.