Long-term trends in income and wealth inequality since 1300.

By Dr. Guido Alfani

Professor of Economic History

Bocconi University (Milan)

Abstract

This article provides an overview of long-term trends in income and wealth inequality, from ca. 1300 until today. It discusses recent acquisitions in terms of inequality measurement, building upon earlier research and systematically connecting preindustrial, industrial, and post-industrial tendencies. It shows that in the last seven centuries or so, inequality of both income and wealth has tended to grow continuously, with two exceptions: the century or so following the Black Death pandemic of 134752, and the period from the beginning of World War I until the mid-1970s. It discusses recent encompassing hypotheses about the factors leading to long-run inequality change, highlighting their relative merits and faults, and arguing for the need to pay close attention to the historical context.

Introduction

In recent years, long-term trends in economic inequality have attracted considerable scholarly attention. This tendency is clearly connected to the Great Recession, which increased the perception of inequality as a potential issue in the general population and made it a central topic in political debates (Wade 2014; Alfani 2021). Academically, the tendency towards a growing interest in inequality has been greatly reinforced by the publication of Thomas Piketty’s famous book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2014). Other books followed shortly, such as Branko Milanovic’s Global Inequality (2016) and Walter Scheidel’s The Great Leveler (2017), which also proved influential among both the civil society and the academy. These books, such as many of the most ambitious publications on inequality of the last decade, have one thing in common: they focus on long-run dynamics, and they make good use of data which have only recently become available.

In the long phase during which inequality and distribution had fallen out of fashion among economists as research topics, economic historians played a crucial role in keeping this avenue of research open.1 Economic historians continue to feature prominently in the current wave of new inequality research, both in their traditional role of producers of new data based on the surviving documentation, and by contributing in an important way to the theoretical discussion about the main drivers of inequality change. Regarding the first point, the expansion of the base of data available to researchers has been particularly spectacular for preindustrial times. We now have reconstructions of wealth and/or income inequality for many European areas that cover systematically the late Middle Ages and the early modern period (see Alfani 2021 for a synthesis of this literature).2 This survey will be deeply informed by the new evidence for preindustrial times. Regarding the economic historians’ contribution to the discussion about the drivers of inequality, it is becoming increasingly apparent that, by looking at inequality and distribution from a long-term perspective, different phenomena become visible, which leads to a need to consider also modern developments (say, from the nineteenth century until today) in a different way. A particularly important result is that the hypothesis originally put forward by Simon Kuznets (1955), according to whom, in modern times, economic inequality growth could be considered a side-effect of economic growth, and specifically of the transition from a mostly agrarian to an industrial economy, no longer appears to be well supported by the historical evidence. As will be seen, this finding has substantial consequences for any attempt to provide an interpretation of modern inequality growth as an unpleasant side-effect of overall positive developments.

Differently from other recent surveys which have focused on more specific historical periods (for example, Alfani 2021 for medieval and early modern times or Bowles and Fochesato 2024 for prehistory), this article will pay particular attention to longer-term dynamics, roughly covering the last seven centuries or so (Section 2): that is, the period for which we now have, for a few countries at least, roughly homogeneous inequality estimates from the late Middle Ages until today. When placed in this longer-term perspective the developments in wealth and income inequality during the last two centuries look different, which tends to change substantially the interpretation of some key historical developments (Section 3).

Seven Centuries of Inequality: An Overview

Producing better data about the distribution of income has always been a major concern among those involved in the scientific study of inequality. After all, Kuznets himself, in his presidential address to the annual meeting of the American Economic Association in 1954, had lamented the «meagerness of reliable information» and openly recognized that his conclusions were based on «perhaps 5 per cent empirical information and 95 per cent speculation, some of it possibly tainted by wishful thinking» (Kuznets 1955, p. 26). While Kuznets’ caveat did not prevent many from taking his wishful hypothesis as if it were rock-solid, it also acted as a powerful incentive to look for more and better evidence. In an early phase, this mostly involved the modern age, with some seminal works appearing on Britain (Williamson 1985) and the United States (Williamson and Lindert 1980) which covered the industrialization period. In parallel, substantial progress was made in providing better estimates of income inequality during the twentieth century (see for example Atkinson 1980). Instead, for many decades the long preindustrial period remained relatively neglected, except for some studies on Britain (Soltow 1968; Lindert 1986). Only toward the end of the twentieth century was a new study of the distribution of income across a whole region (Holland, in the Northern Low Countries) published, although it included very few data points (just two from 1561 to 1732, plus a third for 1808) and was based on such an imperfect indicator of household incomes as the rental values of houses (Van Zanden 1995). For almost another twenty years, this study remained an isolated exception.

This relative neglect was partly explained by the objective difficulty of studying income inequality for preindustrial societies given the scarcity of usable historical sources, itself the consequence of fiscal systems that tended to tax “directly” wealth, but not income (Britain introduced for the first time a personal income tax in 1799. Atkinson 2004). In much of Europe, the situation would have been different if scholars had focused on the distribution of (taxed) wealth, but a consolidated tradition in economics tended to consider it less important than the distribution of income and this somewhat stifled research. The situation started to change from 2012, when the project EINITE (Economic Inequality across Italy and Europe, 1300-1800), generously funded by the European Research Council, began its activities.3 The timing was fortunate, because soon afterwards Thomas Piketty was successful in his double objective of «[placing the] study of distribution and of the longrun back at the center of economic thinking» (Piketty 2015, p. 68), and of convincing the scientific community that wealth inequality was crucial for a proper understanding of long-run distributive dynamics (Piketty 2014).

Piketty himself helped significantly to expand the base of accumulated data on lung-run inequality trends, through his works with economic historians Gilles Postel-Vinay and Jean-Laurent Rosenthal on wealth inequality in France during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Piketty, Postel-Vinay and Rosenthal 2006; 2014). For the preindustrial period, the first region for which a long-run reconstruction of trends in wealth inequality was published is northwestern Italy, and particularly the domains of the Sabaudian State, for which time series of different inequality indicators spanning the five centuries from ca. 1300 until 1800 are now available (Alfani 2015). Other Italian pre-unification states were soon to follow,4 as did studies of other European regions among which Germany is particularly noteworthy as, so far, it is the only non-Italian part of Europe for which we have available a homogeneous times series of wealth inequality measures pushing as far back as the fourteenth century (Alfani, Gierok and Schaff 2022). All these studies of preindustrial inequality applied a homogenous technique to highly comparable historical sources in order to reconstruct regional-level wealth distributions based on substantial samples of local communities.5

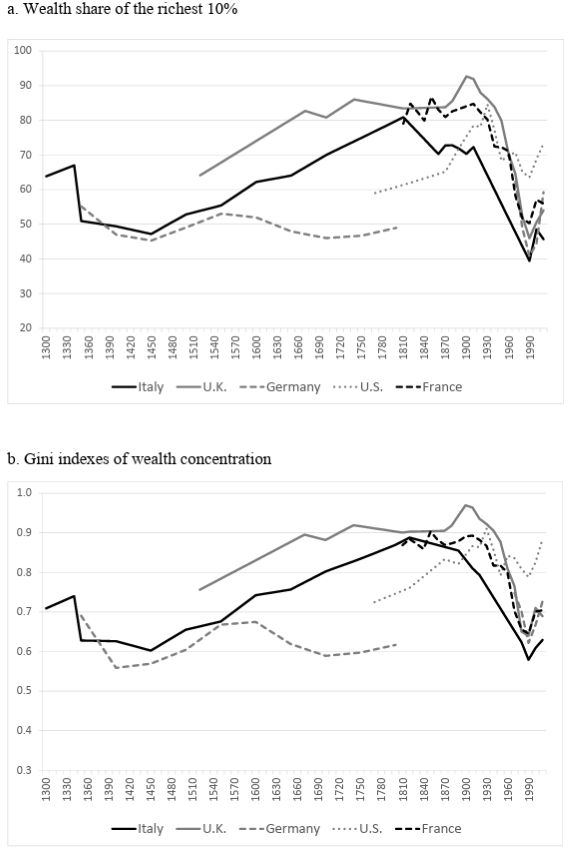

Figure 2.1 reports information for the five world areas for which we currently have the longest time series of wealth inequality: Italy (which for the period preceding national unification in 1861 is presented as an average of four different states), France, Germany, the United Kingdom (the earlier estimates refer to England only), and the United States. It might appear surprising that a relatively young country such as the United States features among those for which we have the longest time series, but this is due to the availability of detailed studies of wealth and income inequality from 1774, then even before the American Revolution (Hanson Jones 1980; Lindert and Williamson 2016). It should also be noted that unfortunately, all the reported cases relate to Western countries as no time series of wealth (or income) inequality of comparable length are currently available for other world areas.6

Figure 2.1 helps to highlight the main “stylized facts” that have been established by recent research on long-run inequality trends (as will be seen, these “facts” are confirmed when moving from a consideration of wealth inequality, to that of income inequality).

First, the long-run tendency appears to have been clearly orientated towards inequality growth. For most of the last seven centuries, and in particular from the mid-fifteenth century until the eve of World War I and from ca. 1980 until today, across the areas of the West for which systematic, regional-level studies are available inequality increased almost monotonically, both looking at the distribution as a whole (as summarized by the Gini index)7 and focusing on the share of the top 10%. The few known exceptions (such as Germany during the seventeenth century, see below) are associated with very specific historical circumstances. We also have some evidence, although admittedly very limited and mostly restricted to some parts of Italy, that inequality was on the rise also in the period immediately preceding the Black Death of 1347-52.8

Second, this tendency towards continuous inequality growth could be interrupted only by truly major catastrophes. This is surely the case for the Black Death, that is the plague pandemic which reached Europe in 1347 and which in a few years covered almost the entire continent killing about half of its overall population (Alfani and Murphy 2017). Thereafter, a second phase of substantial inequality decline was triggered by World War I, continued during the interwar period and was further reinforced by World War II.

A third and final “stylized fact” is somewhat more technical: as can clearly be seen by comparing panel a and b of Figure 2.1, the tendencies in the wealth share of the richest tend to match very closely those in overall inequality. In other words, we find empirically that when the wealth share of the top 10% (or of smaller percentiles, up to, say, the top 1% after which in some settings the measures become somewhat erratic and risk depending on the fortunes of few individuals) increases or declines, so does overall inequality as measured with a Gini index or similar indexes. This appears to be entirely reasonable, but it must be pointed out that it is an empirical regularity, not a statistical necessity. The fact that the dynamics affecting the top of the distribution tend to shape the overall trend in inequality has been amply documented for today societies (Atkinson, Piketty and Saez 2011; Alfani and Schifano 2021) and it has recently been confirmed for preindustrial ones (Alfani 2021). This has two practical advantages: firstly, whenever the sources available only allow us to reliably reconstruct the wealth share of the richest, we can assume that this is informative of more general developments. Secondly, this allows scholars to present their main results about inequality tendencies by discussing top shares only, which helps in making those results more accessible to the civil society.

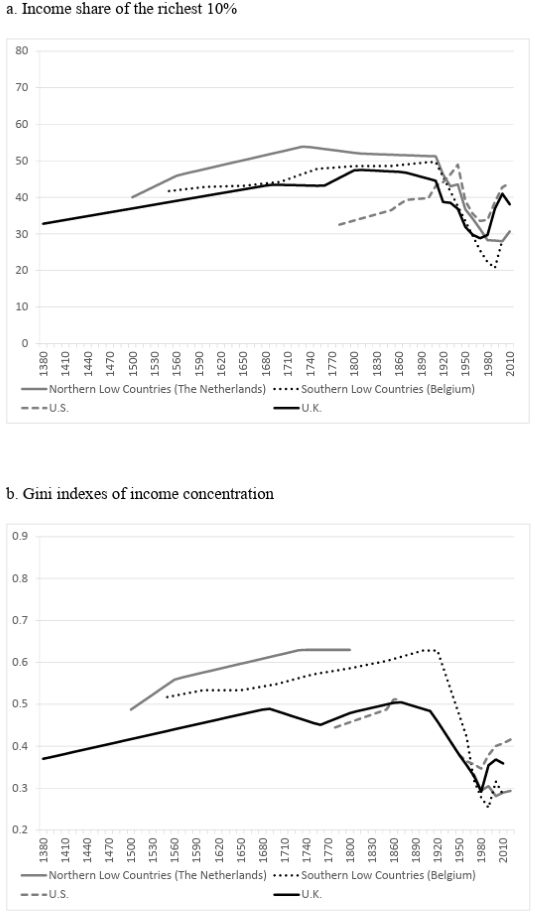

These three stylized facts, which are clearly visible from data on wealth inequality, are entirely confirmed by an analysis of the more limited information available for long-run income inequality trends. Figure 2.2 covers the four world areas for which we have the best information: the Low Countries (nowadays Belgium and The Netherlands), the United Kingdom (the earlier estimates refer to England and Wales only), and the United States. Again, a long-term tendency towards inequality growth can easily be detected, as well as the temporary inversion in the trend triggered by World War I. Unfortunately, we do not have information about the immediate consequences of the fourteenthcentury Black Death, but some evidence, and in particular that for real wages, strongly supports the view that the terrible pandemic had “equalizing” consequences for income comparable to those which we can observe more directly for wealth (Alfani 2022).

The way in which a major pandemic might affect inequality is worthy of some additional discussion, also given the scientific and societal relevance that the topic has acquired during the recent Covid-19 crisis. A first point to make, is that in the face of an event leading to the death of about half the overall population, such as the Black Death, «[a] reduction in income inequality is indeed what we should expect given that for a long period labour became scarce, leading real wages to increase and to a rebalancing of labour and capital income. […T]here is also evidence that severe labour shortages led to a reduction in the skill premium […]. Consequently, labour income itself came to be more evenly distributed.» (Alfani 2021, p. 24). Beyond real wages, we have many other hints that the incomes and the living conditions of the lower strata were improving; this is reflected, for example, in better conditions contractually awarded to different categories of rural workers (Dyer 2015). Increased incomes for the lower strata would lead not only to declining inequality of income, but also of wealth: for a few years after the Black Death, a larger part of the population had the means to acquire property, sometimes for the first time. In this, it was also helped by the fact that, in the post-pandemic period, much more property than usual was put up for sale in the housing and land market. There were two reasons for this: firstly, in the aftermath of the terrible mortality crisis many people found themselves with more property than they wanted or needed, either because they had inherited it or because their household had shrunk in size, making part of their lands redundant or simply impossible to work properly (also due to the high cost of hired labour). Secondly, the process of inheritance itself had tended to fragment property (making it easier or more convenient to sell) simply because given the partible inheritance systems which prevailed in many European areas on the eve of the Black Death (Goody, Thirsk and Thompson 1978), patrimonies came to be divided evenly among many inheritors. The process of inheritance, then, reduced wealth inequality both directly, by breaking down patrimonies, and indirectly, that is by flooding the land market with property and making it easier for the lower strata to buy at least some of it (Alfani 2021; 2022; 2023). As a result, in Italy the Gini index of wealth inequality declined substantially, from a level of just over 0.7 ca. 1300 to about 0.6263 in the immediate post-pandemic decades. A similar tendency has been reported for southern France, where we have information for a few cities only. In Toulouse, for example, the Gini index of wealth inequality declined from about 0.75 in 1335 to about 0.61 in 1398 (Alfani 2022, p. 9).

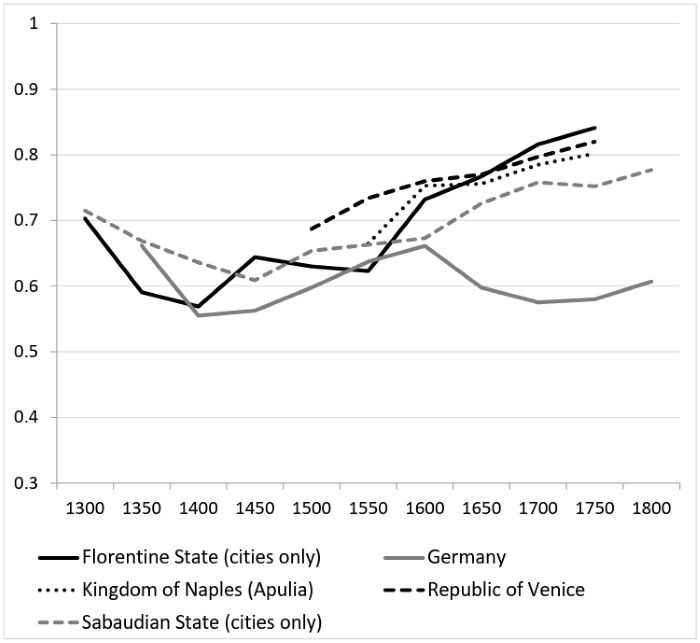

Explaining how the Black Death might have triggered a phase of substantial inequality reduction, then, is relatively straightforward. But plague had come back to Europe and the Mediterranean, after centuries of absence, to remain, and for centuries large-scale plague epidemics became a recurring scourge. And yet, to the best of our knowledge, never again were egalitarian effects of the kind produced by the Black Death encountered. Admittedly, we do not know much about the first postBlack Death plagues. The situation is different for the seventeenth century, when central and southern Europe suffered what are usually considered to have been the worst plagues affecting Europe after the Black Death (Alfani 2013; Alfani and Murphy 2017), with regional mortality rates sometimes reaching 30-40 per cent: sufficiently close to those estimated for the Black Death for us to expect a comparable distributive impact. Instead, if we look at the tendencies in wealth inequality in northern Italian states, such as the Sabaudian State in the northwest and the Republic of Venice in the northeast, around the plague of 1630 which killed about 35% of the overall population of the region, we cannot see even a temporary halt in a trend orientated towards monotonic inequality growth (Figure 2.3).

Why was the distributive impact of plague in Italy so different in the seventeenth century compared to the fourteenth? To answer the question, we can consider the mechanisms that have been highlighted to explain inequality reduction after the Black Death – none of them appears to have been at work during these seventeenth-century episodes. First, bearing in mind that what we can observe directly

is the distribution of wealth, not of income, we can consider the fact that no increases in real wages took place in northern Italy after the 1630 plague, nor in central Italy after the 1656-57 plague which was equally terrible and affected precisely the Italian regions that had been spared in 1630 (Alfani and Percoco 2019; Rota and Weisdorf 2020). Consequently, there is little reason to presume that the lower strata had more resources to acquire property on the housing and land market. At the same time, far less real estate was being put up for sale than in the post-Black Death period, because also the other crucial mechanism – inheritance-induced patrimonial fragmentation – no longer worked in the same way. When it became clear that plague had turned into a permanent feature of their environment, the Italians, as well as the other Europeans, adapted, and did so by modifying their institutions. Although inheritance systems throughout Italy remained formally partible, in the centuries after the Black Death the practice spread of protecting the largest patrimonies from the risk of dispersion by recurring to institutions, such as the fideicommissum (entail) that required that the bulk of the family patrimony be transferred unaltered from one generation to the next. The surviving historical sources provide substantial evidence of this process, for example for Tuscany where the fideicommissum, rarely used before the Black Death, by the second half of the fifteenth century had become commonplace (Leverotti 2005, p. 167; Alfani 2023, p. 292). This allowed especially the richest families to avoid the undesired “egalitarian” consequences of inheritance, and to make their patrimonies more resilient against large-scale crises.

An important takeaway lesson from this brief discussion of the distributive impact of plague in preindustrial Italy, is that the final consequences of a major epidemic or pandemic do not depend solely on mortality rates (although they are one key variable) but on a much broader set of parameters, which we can refer to as the “historical context”. For example, the reason why real wages did not increase (and income inequality did not reduce correspondingly) after the 1630 plague in northern Italy, is that in the specific context of high competition in manufacture and trade from northern European countries with easier access to the Atlantic Trade, such as the Dutch Republic, merchants and entrepreneurs operating even in such a relatively advanced economy as the Republic of Venice took the localized crisis that they suffered (northern Europe was relatively spared by plague during the seventeenth century) as an indication that they were finally done. So they retrenched and switched much of their investment from manufacture to land (promoting further concentration of real estate in few hands). The negative shock to the demand for labour that ensued seems to have entirely compensated for the negative shock to the offer of labour, which the plague itself had caused simply by killing off one-third of the workforce (Alfani and Percoco 2019; Alfani 2022).

The historical context is also crucial in explaining what is, so far, the main known exception to the general trend in wealth or income inequality reported for the early modern period: Germany. There, the seventeenth century was characterized by a phase of inequality decline that puts Germany in direct contrast to all the other areas for which we have information. This includes a range of Italian preunifications states, as detailed in Figure 2.3, as well as (probably) England (Figure 2.1) and the northern and southern Low Countries (to compare Germany with the Low Countries, whose inequality trend is shown in Figure 2.2 but refers to income, not wealth, we need to make the assumption -entirely reasonable for a preindustrial, mostly agrarian society- that at least in the medium and the long run income and wealth inequality were bound to move in the same direction). The Gini index for Germany (calculated on a sample of communities, both urban and rural, placed within the geographical boundaries of nowadays Germany, as the country did not unify before 1871: see Alfani, Gierok and Schaff 2022), which was just below 0.68 ca. 1600, had declined to about 0.62 by 1650, and reduced further, to a bottom level of 0.59, by 1700. This is much lower than the average of 0.80 reported for Italy as a whole based on historical sources entirely analogous to those used for Germany and produced with the same estimation method.

Like northern Italy, Germany was badly affected by plague in the first half of the seventeenth century. Indeed, the same outbreak which reached Italy in late 1629 and spread across the North, plus Tuscany, during the following two years had entered the Peninsula together with the Imperial armies involved in the War for the Mantuan Succession. Until that moment, the Italian health authorities had been able to prevent the infection from spreading across the Alps, while most of Germany had already been ravaged by plague during 1627-29. We have no reasons to believe that plague led to higher mortality rates in Germany than in northern Italy (the opposite is probably true: Eckert 1996; Alfani 2013). What makes Germany stand apart, then, is that in about the same period it was affected by the worst plague after the Black Death, and by the most devastating conflict of preindustrial Europe: the Thirty Years’ War of 1618-48. While it is difficult to disentangle the impact of the war from that of the epidemic, an exercise in difference-in-differences analysis (using the Sabaudian State as a counterfactual, as it was part of the Holy Roman Empire and was affected by plague in ways similar to Germany, but only marginally experienced war in its own territory) provided support for the view that most of the reduction in inequality observed in seventeenth-century Germany was war-induced (Alfani, Gierok and Schaff 2022). In recent literature, the point that devastating wars have a strong “leveling” power has been strongly made by Walter Scheidel (2017) for preindustrial societies, and by Thomas Piketty (2014) for the World Wars period. And yet, the point has also been made that throughout medieval and early modern times, the Thirty Years’ War is the only example of a conflict devastating enough to cause inequality reduction – overcoming an opposite effect of war, that of leading to inequality growth because of increases in per-capita taxation in the context of regressive fiscal systems (Alfani and Di Tullio 2019; Alfani 2021; Schaff 2023). But on a closer look, the factors that led, from 1914 to 1945 (and beyond) to a reduction in both income and wealth inequality are also much more complex than war devastation tout court; for example, taxation (this time of a progressive kind) surely played an important role as well. Discussing the World Wars period provides an excellent opportunity for a more in-depth analysis of different views about the determinants of long-run inequality growth, and so it will be accomplished in the next section.

Economic Inequality Change in the Very Long-Run

As recalled in the Introduction, Kuznets’ famous “inverted-U” hypothesis played a crucial role in promoting the first systematic studies of long-run inequality trends. It also remains very popular among economists and other social scientists, notwithstanding the fact that, based on the accumulated information that we now have available, the Kuznets Curve idea has clearly become “obsolete”, as Peter Lindert already argued over twenty years ago (Lindert 2000). There are two reasons for this. First, regarding the rising phase of the curve, the view that it was the consequence of industrialization, or more generally of economic growth, runs contrary to the now abundant evidence that, in the long run, inequality of both income and wealth started to grow from much earlier than the Industrial Revolution and that, in many historical settings, inequality growth happened in the complete absence of economic growth (see below for further discussion). Second, regarding the declining phase of inequality, Kuznets’ forecast (made in 1955) of inequality reaching (and remaining at) a relatively low level was truly tainted by “wishful thinking”, as he himself had feared: just consider the inversion in the inequality trend experienced by most western countries after the 1970s, clearly visible in Figures 2.1 and 2.2. But there is more: when looking at recent interpretations of the declining phase of the Kuznets Curve (which in western countries began in the first decades of the twentieth century) it is apparent that they are markedly un-Kuznetsian, focusing much more on the levelling power of catastrophes and on the distributive power of progressive taxation than on structural changes in the economy.

Consider levelling. It seems clear that the ability of war to produce “egalitarian” effects on the wealth distribution is strongly dependent upon the scale of destruction of material wealth that it is able to induce. In fact, as seen in the earlier section, before World War I only the Thirty Years’ War of 161848 was “destructive enough” to have demonstrably caused substantial and long-lasting levelling.

From this point of view, it is also clear that World War II, which was able to project physical destruction well beyond the frontline (think of carpet-bombing) and was characterized by a much more mobile kind of warfare compared to World War I, had a much greater potential for causing a levelling of material wealth. For example, Scheidel observed that in the case of Japan (which, differently from Europe, started suffering from physical destruction of wealth in its home territories only in the final phases of the war),

«[b]y September 1945, a quarter of the country’s physical capital stock had been wiped out. Japan lost 80 percent of its merchant ships, 25 percent of all buildings, 21 percent of household furnishings and personal effects, 34 percent of factory equipment, and 24 percent of finished products. […] The large majority of these losses were directly caused by air raids. […] The firebombing of Tokyo during the nights of March 9-10, 1945, which even by conservative estimates killed close to 100,000 residents and destroyed more than a quartermillion buildings and homes across an area of sixteen square miles, was only one outstanding episode; so were the annihilation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki five months later. […S]ome 40 percent of the built-up area of sixty-six cities that had been bombed was destroyed» (Scheidel 2017, pp. 121-2).

Impressive as the destruction of physical capital could be, the World Wars were equally destructive of financial capital and from this point of view there is no doubt that World War I was as much a “great equalizer” as World War II, and maybe even more so. This is a second factor that Scheidel singles out as a war-related “levelling force”, and the same point had been made, a few years earlier, by Thomas Piketty. According to the latter, Word War I “destroyed” financial capital in part because of the loss of foreign investments, of the kind that occurred massively because of expropriation in Russia after the October Revolution of 1917. But the most important factor was war-related hyperinflation, triggered by the suspension of the gold standard and by reckless deficit spending; then, «[a]fter the war, all countries resorted to one degree or another to the printing press to deal with their enormous public debts. Attempts to reintroduce the gold standard in the 1920s did not survive the crisis of the 1930s» (Piketty 2014, pp. 135-6). As a result, inflation became a dramatic problem in countries such as Germany or France, where during 1913-50 the average yearly inflation was 17% and 13% respectively. Again in Piketty’s words (2014, p. 184), this led to a sort of expropriation through inflation, which tended to affect relatively more the richest strata of society because they owned more financial capital and/or relied upon rents fixed in nominal values. The fact that the wealth elite suffered more than all others from the destruction of capital (physical and financial) is confirmed by a recent study of Britain, where World War I wiped out 59% of the wealth of the 1,500 richest dynasties compared to a loss of 38% in the general population; these proportions were 26% and 16% respectively after World War II (Cummins 2022, S4, pp. 60-1). In Germany, the income share of the “one-percenters” first rose in the initial phase of the war (from 18% in 1914 to 23% in 1917), then fell sharply, to about 11% in the 1920s, and only resumed growing from the onset of the Nazi government in 1933 – until World War II inverted the tendency again (Bartels 2019, pp. 678-82). The wealth share of the top 1% followed a similar trend (Albers, Bartels and Schularick 2022, p. 3).

The case of the German one-percenters at the onset of World War I and during the Nazi rearmament campaign of the 1930s allows us to highlight the fact that, for the economic elites, war represented both a great danger to their fortunes and a great opportunity for further enrichment, so that the net outcome, in terms for example of top wealth shares, depends on the balancing of two contrasting forces (see Alfani 2023 for further discussion of this point). This argument is similar, on principle, to that made previously about the general impact of war in a preindustrial context: given that medieval and early modern fiscal systems were overall regressive, any increase in per-capita taxation in wartime, as well as during peacetime to build up military capacity and to repay the public debt made during crises (of a military nature or otherwise) also tended to push up (post-tax) income inequality. In time, this also transferred to wealth inequality, through the mechanism of savings (Alfani and Di Tullio 2019; Alfani 2021; 2023). But from this point of view, we must highlight a structural difference between the modern, and pre-modern period: by the time the major conflicts of the twentieth century erupted, fiscal systems had become overall progressive. Indeed, the World Wars contributed crucially to making them ever more progressive. As argued by David Stavasage (2020, p. 274), «[i]n a context of mass mobilization for war it was possible for the political left to create new fairness-based arguments for steeply progressive taxation. If labor was to be conscripted, then the same should be true of capital». It is not by chance that in the United States, the historical maximum rate of the personal income tax was reached in 1944-45, at 94%. In the United Kingdom, the historical maximum established in 1919 with a top rate of 50% was roundly beaten in the following years, with an all-time maximum reached in 1945 at 97.5%; top rates had been below 10% in the years immediately preceding World War I (Atkinson 2004; Alvaredo et al. 2013). Taxation on inheritances, which affects the wealth distribution directly, followed exactly the same pattern, becoming both more intense (with top rates of the estate tax in the order of 70-80% in the United Stated from the 1930s) and more progressive (Piketty 2014, pp. 644, 651-2; Scheve and Stavasage 2016, pp. 100-8). Wartime “conscription of labour” could have helped to create the conditions for substantial inequality decline also by leading to stronger labour unionization in certain phases, such as the immediate aftermath of World War I. However, in countries such as Italy or Germany, where reaction against these social and political developments favoured the establishment of fascist regimes and a re-balancing of the bargaining power to the advantage of the economic elite, we observe clear signs of rapid income inequality decline being suddenly replaced by inequality growth in the interwar period (Gómez León and De Jong 2019; Gabbuti 2021; Gómez León and Gabbuti 2022).

While the current literature, supported by a much larger amount of data about historical inequality than was available in the mid-twentieth century, does not support Kuznets’ views about the determinants of inequality change, his “inverted-U” idea might be considered still valid as a description of the patterns followed by income and wealth inequality in western countries from the beginning of the nineteenth century until the 1970s. The inversion of the trend from the 1980s, as well as the newly-available evidence about inequality decline after the Black Death, led Branko Milanovic (2016) to propose the idea that, across history, a sequence of “Kuznets waves” is to be found; Figure 2.1 shows this apparent wavelike movement. Apart from the shape, however, the various “inverted-Us” found in sequence across history would have little in common. While Milanovic acknowledges that, in industrial times, Kuznetsian factors such as structural change or urbanization might have shaped the trend, for him in preindustrial times the observed waves were the consequence of “idiosyncratic events”, such as major epidemics and wars for the declining phases, and the discovery of the Americas and the opening of the Atlantic trade routes for the rising phase reported for early modern times (Milanovic 2016, pp. 50–3).

Fascinating and effective as Milanovic’s interpretation is, there is some room for criticism. First, there is reason to doubt that, to truthfully describe history and to understand the deep sources of inequality change, sticking to Kuznets’ lexicon is appropriate (can we describe the phase of inequality growth from ca. 1450 until 1914, and inequality decline from 1914 until the 1970, visible in Figures 2.1 and 2.2 for wealth and income respectively, as an “inverted-U” spanning five centuries and more?). As has been argued elsewhere, «Between catastrophes, the tendency was almost invariably for inequality to grow, as per inertia. Hence, waves notwithstanding, the underlying inequality trend was oriented upwards: which is something that Milanovic did not detect, but which is possibly the most important historical development we have to explain» (Alfani 2021, p. 38).

The second reason for criticism, and maybe for some concern, is that the very idea of a sequence of Kuznets curves or “waves” holds the promise – especially in a period of inequality growth such as the one that we are currently experiencing – of inequality reduction at some point in the future. But when, precisely? Milanovic himself carefully avoids making precise forecasts, simply stating that there are «forces that we may hypothesize would lead rich countries onto the downward portion of the second Kuznets wave [which began in the 1980s]. […T]he peak level of inequality in this wave (which most countries have not yet reached as of this writing, in 2015) is very probably going to be less than the peak of the first Kuznets wave. The reason lies in the number of automatic inequality ‘reducers,’ in the form of extensive social programs and state-funded free health and education» (Milanovic 2016, pp. 116-7). The “benign forces” that, according to Milanovic, might ultimately lead to an inversion of the trend include political changes leading to more progressive taxation; the race between education and skills; the dissipation of the rents accrued during the technological revolution of the 1990s and the 2000s; income convergence at the global level. But eight years after Milanovic formulated the hypothesis of future inequality decline, western countries are still to experience it – and most definitely, they are still to experience any substantial political shift towards more progressive taxation and an equalization in access to good-quality education.

From the point of view of fiscal reform and provision of welfare, Western countries appear to continue to be moving along a path which is leading them away from the very progressive fiscal systems that emerged from the World Wars period and from the “welfare state” policies that developed fully in the thirty years or so immediately following the end of World War II (this path began with the reforms introduced in the 1980s by President Ronald Reagan in the United States and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom). This is an important point, which leads us to address a crucial debate: that about the connection between economic growth, inequality change, and progressive taxation. A well-known argument, developed by a team of inequality experts, is that if we focus on rich countries (the OECD club) from ca. 1960 until today, reductions in the progressive character of taxation did not lead to significant differences in average yearly growth rates of per-capita GDP, but did lead to substantial differences in the tendencies of economic inequality. In other words, reduction in progressivity of taxation (which is not the same thing as a reduction in total fiscal pressure) does not appear to provide any positive stimulus to economic growth, while fostering substantial changes in distribution (Alvaredo et al. 2013; Piketty and Saez 2013; Piketty, Saez and Statcheva 2014). This position clearly runs counter to a long tradition, from Kuznets to modern economists such as Angus Deaton (2013), according to which rising inequality is basically a benign phenomenon: a side-effect of economic growth, with growth itself understood as “a rising tide that lifts all boats”, although not all to the same level.

Overall, the historical experience of the West does not offer much support to this view. Firstly because, as already mentioned, from the 1980s until today similar patterns in economic growth have been associated with diverging tendencies in the matter of distribution, with English-speaking countries experiencing much higher inequality growth compared to other countries, for example in continental Europe, where fiscal progressivity resisted better (compare, in Figure 2.2, the United States and the United Kingdom with Belgium and The Netherlands). This difference has also been described as one between countries following a “U-shaped” path in economic inequality in the period from World War I to the early twenty-first century, and others following a “L-shaped” path (Alvaredo et al. 2013, pp. 5-7). Secondly because, if we take a longer-run perspective, cases abound in which secular phases of substantial inequality growth took place in the absence of economic growth. This is apparent for Italy, which from the early modern periods was one of the main victims of the socalled “Little Divergence”, that is the process which set northern Europe on a quicker growth path than southern Europe. Among the most advanced Italian economies, the Florentine State was the first to experience stagnation, already from the early sixteenth century. The Republic of Venice resisted longer against northern competition, at least until the combined effect of the plague of 1630 and of the extenuating war against the Ottoman Empire for the control of the island of Candia (nowadays Crete) during 1645-1669 fatally compromised its residual economic ambitions (Alfani and Percoco 2019). Even the Sabaudian State, which during the eighteenth century would become the most economically dynamic area of the Italian peninsula, suffered badly during the seventeenth century, due again to the 1630 plague and the civil war of 1638–1642, with its long-lasting negative consequences (Alfani 2015). And yet, if we look at Figure 2.3, in each and every one of these states economic inequality continued to grow without pause.

There are many reasons why, in a preindustrial context, inequality could grow even in the complete absence of economic growth. A general point is that in the long run – indeed, from the introduction of farming and the herding of animals in prehistorical societies until today – growing inequality in the access to economic resources can be seen as the consequence of the development of resilient hierarchies of power and coercive force, including through the process of “state formation” (Scheidel 2017, pp. 5-9; for a recent synthesis of research on preindustrial inequality, Bowles and Fochesato 2024). For medieval and early modern times, recent research has focused on the distributive consequences of the rise of the so-called “fiscal state”, which led to continuous increases in per-capita taxation (Alfani and Di Tullio 2019; Alfani 2021; 2023). While this process is undoubtedly connected to the strengthening of state institutions, à la Scheidel, it must also be noticed that the stimulus to increase per-capita taxation came from the increasing cost of war or even of simple defence, due to the growing cost of military equipment and the increases in the efficient size of armies associated with the so-called “military revolution” in early modern Europe (Parker 1988; Rogers 1995). This stimulus was felt by all European states (as they were all watchful of their neighbours’ military innovations and investments), and all had to take steps to improve their fiscal capacity (that is, to increase taxation per-capita), whatever the conditions of their economies. This is why, in this context, fiscally-induced inequality growth occurred in ways which were largely independent from economic growth.

As mentioned above, the reason why, in preindustrial times, increases in per-capita taxation led to increases in economic inequality is that preindustrial fiscal systems were regressive, with the richest being taxed less than the poor in proportion to their income or wealth. A study of the Republic of Venice estimated that, circa 1550 when the overall fiscal pressure of the central state amounted to about 5% of GDP, the effective fiscal rate weighing on the income of the poorest 10% was in the range of 5.4-6%, declining monotonically moving up the income pyramid so that, for the richest 5%, the rate was only 3.9-4.4%: a substantial difference, considering that the relative advantage of the economic elite was not only preserved across centuries but was expanded by the progressive intensification of fiscal pressure (by 1750, the poorest 10% were taxed for 9.3-10.3% of the income, while the richest 5% for just 6.6–7.6%. Alfani and Di Tullio 2019, pp. 145-65).

The reason why a system so clearly unbalanced in favour of the economic elites could prove compatible with an overall stable society, is that such a society embraced an idea of justice deeply different from that of modern western societies, an idea which did not require equal treatment of all because it mirrored the formal hierarchy of distinct orders or ‘estates’ to which every individual belonged, as was the norm until the French Revolution of 1789 (Alfani and Frigeni 2016; Alfani 2023).9 In such a cultural context, which «coded inequality as both necessary and just» (Jackson 2023, p. 277), the only requirement for making the system acceptable was that the rich paid more taxes than the poor: which they surely did (circa 1550, the richest 5% of the Republic of Venice paid 46.9-48.7% of all taxes to the central state), only this was less than they would have had to pay under a proportional, not even a progressive, fiscal regime. From our modern perspective, what is interesting is that in recent years the argument that the rich should not be taxed more than they currently are because they already pay most of the taxes, and that the fiscal systems should be made less, not more, progressive has become part of the political debate in many western countries: an argument which would have been perfectly understandable if voiced by a Venetian patrician of the sixteenth or seventeenth century, but that is decidedly more debatable in the context of a modern western democracy.

The apparent contrast between how, today, distribution works in practice, and what we could expect to happen in theory in an institutional framework shaped by modern western values, has led many social scientists and inequality experts to voice their concern. Already in 2014, Piketty was making the point that if the ongoing tendency towards concentration of capital continued, a level might be attained which is «potentially incompatible with the meritocratic values and principles of social justice fundamental to modern democratic societies» (Piketty 2014, p. 34). For him, this tendency would have continued until the rate of return on capital, r, remained higher than the growth rate of national income, g, and as long as wealth remained highly inheritable. While, as a theory, Piketty’s position has been much criticized (see for example Lindert 2014; Blum and Durlauf 2015; Ray 2015), his concerns remain entirely justified – especially because, as he clarified in later works, the “proprietarian societies”10 that emerged after the French Revolution can prove no less effective than preindustrial ones (which, as seen above, were explicitly hierarchical) in legitimizing high inequality (Piketty 2020; about the shift in how inequality was perceived after the French Revolution, also see Alfani and Frigeni 2016 and the synthesis by Jackson 2023, pp. 277-9).11

In terms of policy implications, Piketty’s recipe is one of sweeping tax reform, including the return to stronger fiscal progressivity and to higher taxation of income and wealth, a recipe on which Piketty elaborated further in subsequent studies (Piketty 2020). Others hold similar views, in general or in relation to specific countries (see for example Saez and Zucman 2019 for the United States). Milanovic addressed this debate from a different angle, arguing that it was capitalism’s final victory against its main twentieth-century ideological adversary, communism, that led the endless pursuit of profit to become a universal objective (in his words, «[w]e live in a world where everybody follows the same rules and understands the same language of profit-making». Milanovic 2019b, p. 3). This, in the context of an uneven initial distribution of capital (Milanovic is appreciative of Piketty’s general argument) and in the absence of ideological competition, would tend to favour inequality growth. Milanovic’s recipe for ensuring that western “liberal meritocratic capitalism” is also “egalitarian” involves fostering «approximately equal endowments of both capital and skill across the population» (Milanovic 2019b, p. 46), but without simply re-proposing twentieth-century policies that appear to be politically difficult to return to and, in a context of high economic globalization, might prove impossible to implement.12

A final point which is worth considering, in this brief overview of the current debate on the causes of long-run inequality change, is that in spite of the demonstrated ability of a few major historical crises to lead to substantial leveling of both income and wealth inequality, in the last years not even a combination of a major financial and economic crisis (the “Great Recession” which began in 2008, followed by the European sovereign debt crisis which peaked in 2010-11), a major global pandemic caused by Covid-19, and a major war in Europe (the Russian invasion of Ukraine which began in February 2022, ongoing at the time of writing) was able to invert the tendency towards further inequality growth.13 This is particularly apparent looking at the income and wealth share of the richest components of society. For example, in the United States the income share of the richest 10% was 42.8% in 2000, 43.9% in 2010 and 45.6% in 2021, while the top 10% wealth share was, at the same dates, 67.9%, 70.9% and 70.7% respectively (World Inequality Database, consulted 25 October 2023). Although some caution is needed, as it might be too early to gauge the ultimate consequences of the most recent crises and of the associated high inflation, the persistence of relatively high inequality appears to have two relevant consequences for our discussion. First, it casts further doubts on any attempts to generalize the supposed leveling power of catastrophes; instead, whether leveling of the kind which might in theory be brought forward by major wars or pandemics also occurs in practice depends on the broader historical context in which the crisis takes place and, crucially, on factors (such as the institutional framework) which are shaped by human agency (Alfani 2021). Second, the exceptional resilience of the rich against the most recent crises has partly been achieved by successfully dodging increases in progressive taxation and, more generally, by avoiding contributing more than other social strata to pay the bill for the crises. In doing this, arguably, today rich are failing to fulfil a social function which, in the western cultural tradition, has been assigned to them from the Middle Ages through most of the twentieth century. This leads to worries which add up to those discussed previously: «[t]his unwillingness to help, while it is not laudable, in principle could be overcome by public institutions; after all, historically, the rich have fulfilled their role as much through the acceptance of a duty towards their country and fellow citizens as through forced contributions and loans (and from the twentieth century, strongly progressive taxation of incomes and inheritances). The fact that this is not happening, all across the West, […] leads us to wonder whether today’s rich, who concentrate in their hands a historically exceptional amount of economic resources, aren’t also using these resources to achieve exceptional control over the political system or just to steer voters away from certain positions. Are they systematically mobilizing political resources to protect themselves from any attempt at selective tax increases? Are they finally acting as gods among men, wrecking democratic institutions […]?» (Alfani 2023, p. 319).

Concluding Remarks

This article has provided an overview of long-run tendencies in inequality of both income and wealth, and of the debate about the determinants of inequality change in history. It has focused on the period from ca. 1300 until today, that is on the period for which, at least for some world areas (mostly in the West), we have some reconstructions of economic inequality at a state or at least a regional level. Over this period, economic inequality has tended to grow continuously – with two exceptions, both associated to large-scale catastrophes: the century or so following the Black Death pandemic of 134752, and the period from the beginning of World War I until the mid-1970s. While the levelling ability of catastrophes themselves has attracted considerable attention, the historical evidence suggests that the impact of events of similar nature (say, major plagues in the fourteenth or in the seventeenth century) and magnitude (for example in terms of overall mortality rates) can be very different, as their consequences are crucially mediated by the historical context. Of particular importance is the political and institutional context existing on the eve of the crisis. For example, major epidemics tend to have deeply different consequences for wealth inequality if they occur in a context of generalized partible inheritance, or in one of impartible inheritance (at least for the elites), while wars, which invariably lead to increases in taxation, can have diametrically opposite effects if they take place in a context of regressive, or of progressive taxation (and if they cause, or not, substantial destruction of financial and/or of physical capital).

Taxation plays a central role in some of the main recent interpretations of factors shaping long-run inequality trends. From the beginning of the twentieth century until today, the tendency towards higher fiscal progressivity of both income and wealth (mostly through taxation of estates or inheritances) from the beginning of World War I, and the inversion of the trend from the 1980s until today, are credited with having played a crucial role in shaping general inequality dynamics. But in the long preindustrial period, when taxation was regressive, it tended to favour continuous inequality growth: especially when, from the beginning of the early modern period, per-capita fiscal pressure started to grow to pay for the higher cost of war and defence, and for servicing a public debt itself accumulated mostly in wartime. More generally, the importance of the institutional framework (of which fiscal systems are just one component; political institutions are another key one) in shaping inequality trends in the long run suggests that we should resist two temptations: first, that of simply dismissing inequality growth as a side-effect of economic growth (a view which, if looked at from a long-run perspective, is simply untenable). Second, that of considering long-run inequality growth as a sort of “natural” process, largely independent of human choice. Instead, as long-run inequality trends are crucially shaped by institutions, it follows that they are crucially influenced by the human agency which shaped those institutions in time. The fact that, across history, human agency has tended to favour inequality growth much more frequently than inequality decline should make us value more the exceptional phase of substantial and enduring equalization which has characterized most of the twentieth century – and maybe, it should make us worry about what we stand to lose.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Think of scholars such as Peter Lindert, Lee Soltow, Jan Luiten Van Zanden and Jeff Williamson.

- Some works pushed even further back in time, looking at the Classical Age (Scheidel and Friesen 2009; Scheidel 2017; Milanovic 2019; and even at prehistory (Borgerhoff Mulder et al. 2009; Bowles, Smith and Borgerhoff Mulder 2010; Bogaard, Fochesato and Bowles 2019; Fochesato, Bogaard and Bowles 2019).

- https://www.dondena.unibocconi.it/EINITE

- Including the Florentine State (Alfani and Ammannati 2017), the Republic of Venice (Alfani and Di Tullio 2019) and the Apulia region in the Kingdom of Naples (Alfani and Sardone 2023).

- For a synthesis of this approach, which has been developed by the EINITE project, and for an overview of the historical sources used, see Alfani 2021; see the publications referring to each specific region for more in-depth information. Note that the reconstructed regional distributions have been produced at 50-year increments (so, for early modern times, 1500, 1550, 1600, etc.), which makes comparison of the series “Italy” and “Germany” in Figure 1 (for the period 1300-1800), and of all series shown in Figure 3, particularly straightforward.

- For preindustrial times, some promising (but as yet unpublished) works include Drixler 2018 and Kumon 2021 for Japan and Canbakal and Filiztekin (2023) for Anatolia in the Ottoman Empire.

- The value of the Gini index varies between 0 (perfect equality: each household or individual has the same income or wealth) and 1 (perfect inequality: one household or individual earns or owns everything).

- Most of the data suggesting a pre-Black Death tendency towards inequality growth refers to the Florentine State/Tuscany; see in particular the expanded database provided by Alfani, Ammannati and Balbo (2023). A recent study of England, in which for a sample of counties wealth inequality during 1280-1319 could be compared to the situation in 1327-32, did not find a clear pattern (Alfani and García Montero 2022, p. 1332).

- Also Piketty (2020) points in this direction when discussing how inequality was legitimized in “ternary” societies divided into orders with very uneven access to economic, social and symbolic resources.

- «[P]roprietarian ideology rests not only on a promise of social and political stability but also on an idea of individual emancipation through property rights, which are supposedly open to anyone […]. In theory, property rights are enforced without regard to social or family origin under the equitable protection of the state. […] Everyone was entitled to secure enjoyment of his property–safe from arbitrary encroachment by king, lord, or bishop–under the protection of stable, predictable rules in a state of laws […]. Everyone therefore had an incentive to derive the maximum fruits from his property, using whatever knowledge and talent he had at his disposal. Such clever use of every person’s abilities was supposed to lead naturally to general prosperity and social harmony» (Piketty 2020, pp. 120-1).

- «[H]ard-core proprietarian ideology [… is] a sophisticated discourse, which is potentially convincing in certain respects, because private property […] is one of the institutions that enable the aspirations and subjectivities of different individuals to find expression and interact constructively. But it is also an inegalitarian ideology, which in its harshest, most extreme form seeks simply to justify a specific form of social domination, often in excessive and caricatural fashion. Indeed, it is a very useful ideology, for people and countries that find themselves at the top of the heap. The wealthiest individuals can use it to justify their position vis-à-vis the poorest: they deserve what they have, they say, because of their talent and effort, and in any case inequality contributes to social stability, which supposedly benefits everyone» (Piketty 2020, p. 125).

- According to Milanovic, equal endowments could be obtained by means of tax policies aimed at: making equity ownership relatively more attractive to small shareholders than to big ones; favouring worker ownership; evening out access to capital by means of inheritance or wealth taxes finalized at providing every young adult with a “capital grant”; making education more accessible and equalizing the returns to education between equally educated people (Milanovic 2019, pp. 47-50).

- Regarding Covid-19 and the Russian-Ukraine war, it could be argued that their inability to reduce inequality also depends upon their relatively modest extent compared to previous inequality-reducing crises such as the Black Death or the World Wars.

References

- Albers, Thilo N. H., Charlotte Bartels, and Moritz Schularick. 2022. “Wealth and Its Distribution in Germany, 1895–2018.” Discussion Paper no. DP17269, CEPR.

- Alfani, Guido. 2013. “Plague in Seventeenth-Century Europe and the Decline of Italy: An Epidemiological Hypothesis.” European Review of Economic History 17 (4): 408–30.

- Alfani, Guido. 2021. “Economic inequality in preindustrial times: Europe and beyond.” Journal of Economic Literature, 59(1): 3-44.

- Alfani, Guido. 2022. “Epidemics, Inequality and Poverty in Preindustrial and Early Industrial Times.” Journal of Economic Literature 60, no. 1 (March): 3–40.

- Alfani, Guido. 2023. As Gods among Men. A History of the Rich in the West. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Alfani, Guido, and Francesco Ammannati. 2017. “Long-Term Trends in Economic Inequality: The Case of the Florentine State, c. 1300–1800.” Economic History Review 70 (4): 1072–1102.

- Alfani, Guido, Francesco Ammannati, and Nicoletta Balbo. 2022. “Pandemics and Social Mobility: The Case of the Black Death.” Paper presented at the World Economic History Congress (25–9 July), Paris.

- Alfani, Guido, and Roberta Frigeni. 2016. “Inequality (Un)perceived: The Emergence of a Discourse on Economic Inequality from the Middle Ages to the Age of Revolution.” Journal of European Economic History 45, no. 1 (November): 21–66.

- Alfani, Guido, and Tommy E. Murphy. 2017. “Plague and Lethal Epidemics in the Pre-Industrial World.” Journal of Economic History 77 (1): 314-43.

- Alfani, Guido, and Marco Percoco. 2019. “Plague and Long-Term Development: The Lasting Effects of the 1629–30 Epidemic on the Italian Cities.” Economic History Review 72, no. 4 (November): 1175–201.

- Alfani, Guido, and Wouter Ryckbosch. “Growing apart in early modern Europe? A comparison of inequality trends in Italy and the Low Countries, 1500-1800.” Explorations in Economic History 62 (2016): 143-53.

- Alfani, Guido, and Sergio Sardone. 2023. “Long-term trends in income and wealth inequality in southern Italy. The Kingdom of Naples (Apulia), sixteenth to eighteenth centuries.” Paper presented at the Explorations in Economic History Workshop on Wealth and Income Inequality around the World, Federal Reserve of Chicago, IL, 7 October 2023.

- Alfani, Guido, and Sonia Schifano. 2021. “Wealth inequality in the long run.” In How Was Life? Volume II , ed. by Jan Luiten Van Zanden et al. 103-23. Paris: OECD.

- Alvaredo, Facundo, Anthony B. Atkinson, Thomas Picketty, and Emmanuel Saez. 2013. “The Top 1 Percent in International and Historical Perspective.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27 (3): 3-20.

- Atkinson, Anthony B. (ed.) 1980. Wealth, Income, and Inequality, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Atkinson, Anthony B. 2004. “Income Tax and Top Incomes over the Twentieth Century”, Hacienda Pública Española / Revista de Economía Pública, 168-(1/2004): 123-141.

- Atkinson, Anthony B., Thomas Piketty, and Emmanuel Saez. 2011. “Top Incomes in the Long Run of History.” Journal of Economic Literature 49 (1): 3–71.

- Bartels, Charlotte. 2019. “Top Incomes in Germany, 1871–2013.” Journal of Economic History 79, no. 3 (September): 669–707.

- Blum, Lawrence E., and Steven N. Durlauf. 2015. “Capital in the Twenty-First Century: A Review Essay.” Journal of Political Economy 123 (4): 749–77.

- Bogaard, Amy, Mattia Fochesato, and Samuel Bowles. 2019. “The Farming-Inequality Nexus: New Methods and Evidence from Western Eurasia.” Antiquity 93 (371): 1129–43.

- Borgerhoff Mulder, Monique, et al. 2009. “Intergenerational Wealth Transmission and the Dynamics of Inequality in Small-Scale Societies.” Science 326 (5953): 682–88.

- Bowles, Samuel, Eric Alden Smith, and Monique Borgerhoff Mulder. 2010. “The Emergence and Persistence of Inequality in Premodern Societies.” Current Anthropology 51 (1): 7–17.

- Bowles, Samuel, and Mattia Fochesato. 2024. “The Origins of Enduring Economic Inequality.” Journal of Economic Literature, forthcoming.

- Broadberry, Steven, Bruce M.S. Campbell, Alexander Klein, Mark Overton, and Bas Van Leeuwen. 2015. British Economic Growth 1270-1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Canbakal, Hülya, and Alpay Filiztekin. 2023. “Inequality in northwestern Anatolia under the Ottomans, 1460–1800 (or 1870).” Unpublished working paper. Cummins, Neil. 2022. “The Hidden Wealth of English Dynasties, 1892–2016.” The Economic History Review 75, no. 3 (August): 667–702.

- Deaton, Angus. 2013. The Great Escape: Health, Wealth and the Origins of Inequality. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Drixler, Fabian. 2018. “Inequality in Eastern Japan, 1650–1870.” Paper presented at the World Economic History Congress, Boston, MA August 1.

- Dyer, Christopher C. 2015. “Golden Age Rediscovered: Labourers’ Wages in the Fifteenth Century.” In Money, Prices and Wages. Edited by Martin Allen and D’Maris Coffman, 180-195. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eckert, Edward A. 1996. The Structure of Plagues and Pestilences in Early Modern Europe: Central Europe, 1560–1640. Basel, Switzerland: Karger.

- Fochesato, Mattia, Amy Bogaard, and Samuel Bowles. 2019. “Comparing Ancient Inequalities: The Challenges of Comparability, Bias and Precision.” Antiquity 93 (370): 853–69.

- Gabbuti, Giacomo. 2021. “Labor shares and inequality: insights from Italian economic history, 18951970.” European Review of Economic History 25 (2): 355–378.

- Gabbuti, Giacomo, and Salvatore Morelli. 2023. “Wealth, Inheritance, and Concentration: An ‘Old’ New Perspective on Italy and its Regions from Unification to the Great War.” Working paper.

- Gómez León, Maria, and Herman De Jong. 2019. “Inequality in turbulent times: income distribution in Germany and Britain, 1900–50.” Economic History Review 72 (3): 1073–1098.

- Gómez León, Maria, and Giacomo Gabbuti. 2022. “Wars, Depression, and Fascism: Income Inequality in Italy, 1900-1950.” LEM Working Papers Series n. 26.

- Goody Jack, Joan Thirsk, and Edward P. Thompson. 1978. Family and Inheritance: Rural Society in Western Europe, 1200-1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hanson Jones, A. 1980. Wealth of a Nation to Be. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Jackson, Trevor. 2023. “The New History of Old Inequality.” Past & Present 259: 262-289.

- Kumon, Yuzuru. 2021. “The Deep Roots of Inequality.” Working paper no. 125 of the Institute for Advanced Study in Toulouse (IAST).

- Kuznets, Simon. 1955. “Economic Growth and Income Inequality.” American Economic Review 45 (1): 1-28.

- Leverotti, Franca. 2005. Famiglia e istituzioni nel Medioevo italiano dal tardo antico al rinascimento. Roma: Carocci.

- Lindert, Peter H. 1986. “Unequal English Wealth since 1670.” Journal of Political Economy 94 (6): 1127-62.

- Lindert, Peter H. 2000. “Three Centuries of Inequality in Britain and America.” In Handbook of Income Distribution. Vol. 1, edited by Anthony B. Atkinson and François Bourguignon, 167–216. Amsterdam and Oxford: Elsevier, North-Holland.

- Lindert, Peter H. 2014. “Making the Most of Capital in the 21st Century.” NBER Working Paper 20232.

- Lindert, Peter H. and Jeffrey G. Williamson. 2016. Unequal gains. American growth and inequality since 1700. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Milanovic, Branko. 2016. Global Inequality: a new approach for the age of globalization. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

- Milanovic, Branko. 2019a. “Income Level and Income Inequality in the Euro-Mediterranean Region, C. 14–700.” Review of Income and Wealth 65 (1): 1–20.

- Milanovic, Branko. 2019b. Capitalism, alone. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

- Parker, Geoffrey. 1988. The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the West, 1500–1800. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge MA.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Piketty, Thomas. 2015. “Putting Distribution Back at the Center of Economics: Reflections on Capital in the Twenty-First Century.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 29 (1): 67–88.

- Piketty, Thomas. 2020. Capital and Ideology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Piketty, Thomas, and Emmanuel Saez. 2013. “Optimal Labor Income Taxation.” Chap. 9 in Handbook of Public Economics, Vol. 5, edited by A. Auerbach, R. Chetty, M. Feldstein, and E. Saez. Elsevier-North Holland.

- Piketty, T., E. Saez and S. Statcheva, “Optimal Taxation of Top Labor Incomes: A Tale of Three Elasticities”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2014, 6(1): 230–271.

- Piketty, Thomas, Gilles Postel-Vinay, and Jean-Laurent Rosenthal. 2006. “Wealth Concentration in a Developing Economy: Paris and France, 1807-1994.” American Economic Review 96 (1): 236-56.

- Piketty, Thomas, Gilles Postel-Vinay, and Jean-Laurent Rosenthal. 2014. “Inherited vs Self-Made Wealth: Theory and Evidence from a Rentier Society (Paris 1872-1937).” Explorations in Economic History 51: 21-40.

- Ray, Debraj. 2015. “Nit-Piketty: A Comment on Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty First Century.” CESifo Forum 16 (1): 19–25.

- Rogers, Clifford J. 1995. The Military Revolution Debate: Readings on the Military Transformation of Early Modern Europe. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Rota, Mauro, and Jacob Weisdorf. 2020. “Italy and the Little Divergence in Wages and Prices: New Data, New Results.” Journal of Economic History 80 (4): 931–60.

- Saez, Emmanel, and Gabriel Zucman. 2019. The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay. New York: Norton.

- Schaff, Felix. 2023. ”Warfare and Economic Inequality: Evidence from Preindustrial Germany (c. 1400-1800).” Explorations in Economic History 89: 1-21.

- Scheidel, Walter. 2017. The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Scheidel, Walter, and Steven J. Friesen. 2009. “The Size of the Economy and the Distribution of Income in the Roman Empire.” Journal of Roman Studies 99: 61–91.

- Scheve, Kenneth, and David Stasavage. 2016. Taxing the Rich: A History of Fiscal Fairness in the United States and Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Soltow, Lee. 1968. “Long-run changes in British income inequality.” Economic History Review 21: 17-29.

- Stavasage, David. 2020. The Decline and Rise of Democracy: A Global History from Antiquity to Today. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Van Zanden, Jan L. 1995. “Tracing the beginning of the Kuznets Curve: Western Europe during the Early Modern Period.” The Economic History Review 48 (4): 643-64.

- Wade, Robert H. 2014. “The Strange Neglect of Income Inequality in Economics and Public Policy.” In Toward Human Development: New Approaches to Macroeconomics and Inequality, edited by Giovanni Andrea Cornia and Frances Steward, 99–121. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Williamson, Jeffrey G. 1985. Did British Capitalism Breed Inequality? Boston: Allen & Unwin.

- Williamson, Jeffrey G., and Peter H. Lindert.1980. American Inequality: A Macroeconomic History. New York: Academic Press.

Originally published by the World Inequality Database (WID), February 2024, to the public domain.