Examining the wealth and power held by robber barons.

Abstract

This paper identifies and analyzes the steps the United States took in its progression to an industrial nation. Launched by the merger movement in the late nineteenth century, vertical and horizontal integration lead to trusts and monopolies in a number of industries. Simultaneously, the labor market was undergoing a number of reforms with the deskilling of workers. The rise of big business was made possible through the growth of the financial sectors and companies such as J.P Morgan. The case study of The Standard Oil Co. highlights the wealth and power that robber barons such as J.D. Rockefeller held during this time period and its continuing affects, including a widening of the distribution of wealth and inequality.

Introduction

In the nineteenth century, the American economy underwent a period of rapid expansion and change as a previously agricultural nation shifted into an industrial one. Following the Civil War, there was an accumulation surge due to new technological advances and managerial reforms that allowed for greater control over workers, price, and output. Mass production of goods soared, as well as a shift that occurred in the labor markets, moving from proletarianization into homogenization. The rise of big business and corporate finance occurred simultaneously and in turn, stimulated the economic growth at the time. This growth, however, was concentrated in the monopolistic fortunes of the robber barons. While a great deal of innovation and progress was seen with the rise of the American industrial and financial markets, it also left the nation with rising inequality and wage gaps that are still seen today.

The Merger Movement

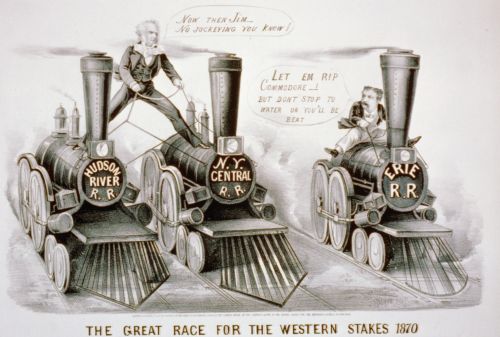

While the majority of businesses industrialized in the 1870s, one industry was ahead of its competitors. According to Alfred Chandler, author of The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (1977), America’s first big business appeared in the 1850s with the railway system. At the time, only major governmental organizations, such as the United States Post Office, were employing more workers and controlling more money than the railroads. Chandler further explains, “The great railway systems were by the 1890s the largest business enterprises in the United States but also in the world… The railroad was, therefore, in every way the pioneer in modern business administration” (1977, p. 204).

The change that the American railroads underwent forecasted what was to come for the rest of American business. Expanding to unprecedented levels in the 1850s, the railroads were responsible for 15 percent of gross private investment in the economy during that period, increasing to 28 percent by the 1890s (DuBoff, 1989). Richard Tedlow, author of The Rise of the American Business Corporation (1991), explains, “… the railroad was critical to American economic growth, and the corporate form was critical to the growth of the railroad” (p. 15). This corporate form that allowed for railroads to expand into big business was facilitated through a surge of consolidations. Successful companies, such as W. H. Vanderbilt’s New York Central Railroad, began to buy, lease, or form trusts with competitors and led to industrial giants, not only within the railroad sector but extending throughout all industries (DuBoff, 1989).

The consolidation movement was discussed above with respect to the railroad system, however, the merger movement occurred throughout all industries in the late nineteenth century. According to DuBoff, “… all those forces making for big business coalesced in a tidal wave of mergers and consolidations” (1989, p. 57), focusing largely on Alfred Chandler’s views on the managerial revolution and technology as those main forces. Chandler believes that big business was a result of inefficiency faced by many industries in the wake of expanding markets and new technology (1977). In order to combat this inefficiency, Chandler asserts that the “visible hand” of management allowed for greater control and supervision of employees and output. In his book, The Visible Hand, he explains,

In many sectors of the economy the visible hand of management replaced what Adam Smith referred to as the invisible hand of market forces. The market remained the generator of demand for goods and services, but the modern business through existing processes of production and distribution, and of allocating funds and personnel for future production and distribution. As modern business enterprise acquired functions hitherto carried out by the market, it became the most powerful institution in the American economy and its managers the most influential group of economic decision makers (Chandler, 1977, p. 1).

Chandler’s argument rests on the belief that progress and innovation with respect to production and larger markets allowed for this change in management (1977). Prior to the industrial revolution, corporations simply did not operate at such a level that they demanded hierarchical administrators. However, once the markets for goods and services expanded, this control over production and workers was required. Corporations could no longer depend on market control to ensure its efficiency. Instead, firms began to account for external market expansion and grow internally through horizontal and vertical integration (ibid).

The merger movement saw a great deal of horizontal integration, as one organization combined with its less successful competition to turn themselves into large multi-unit companies. Within horizontally integrated businesses, managerial power existed over the various departments, each with their own head (DuBoff, 1989). By acquiring the competition, these large-scale companies were able to control prices and output over the entire market, as if it was a true monopoly (Cashman, 1984).

As horizontal integration allowed for a greater distribution of power, vertical integration involves a top-to-bottom accumulation of power. Vertical integration allowed for greater production efficiency due to its ability to reduce costs (Cashman, 1984). Chandler explicates that the first successful big businesses in the United States were those that implemented a higher level of management, responsible for connecting the production and the distribution of goods. In many firms, the corporate manager facilitated “the flow from the suppliers of raw materials through all the processes of production and distribution to the retailer or ultimate consumer” (Chandler, 283). Whether horizontally or vertically integrated, the internalization of management led to lowered transaction costs, increased production and more competitive prices (ibid.).

Innovations such as horizontal and vertical innovation cause the Gilded Age to often be remembered as a time of continuous prosperity and growth. However, in many industries, such as oil and steel, this is not the case (Cashman, 1984). Demand was always changing while excess capacity was a constant fixture since 1873. Accumulation can only continue as long as capacity does not outstrip demand, a problem that is often inherent to a capitalist economy, causing firms to grow too large for their own markets, forcing companies to drop their prices in order to produce some profits. Eventually, the entire market must drop their prices as well. This cycle is known as destructive competition (DuBoff, 1989).

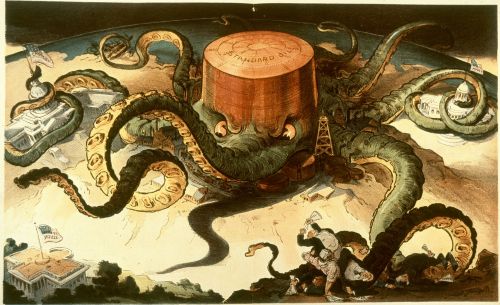

This problem of destructive competition was rampant in the late 1800s, leaving many firms in a trapped, diminishing market. In hopes of combating destructive competition, corporations sought to establish greater control over production, prices, and profits through a number of agreements. Informal agreements such as gentlemen’s agreements quickly lead to cartels and eventually, trusts. Since trusts did not require a state charter, larger corporations were able to force smaller firms to secede control, simply issuing trust agreements entitling them to a percentage of profits (Prechel, 2000). As seen with the Standard Oil Company, trusts were formed between firms to maximize control and expansion, with hopes of eventually monopolizing. The Standard Oil Trust established by Rockefeller gave trustees control of more than 90% of the oil industry. Growing wary of the power and size of companies such as Standard Oil, the federal government implemented the Sherman Anti-Trust Act in 1890 in order to restrict monopolies (ibid.). However, the Standard Oil Company, along with a handful of other trusts of the period, survived as either a monopoly or oligopoly within their respective industries well into the twentieth century (DuBoff, 1989).

The holding company of the late nineteenth century was critical in the development of the modern corporation, providing the foundation for growth. Harland Prechel’s book Big Business and the State focuses on the rise of corporations and their legacy between the 1880s and the 1990s. However, he addresses that the expansion of business corporations began as early as the first half of the nineteenth century due to factors such as an increase in foreign demand markets following the Napoleonic Wars and the introduction of canal and railway transportation. He explains, “As the number of business enterprises increased, the demand for business charters (i.e., certificates of incorporation) increased. These charters focused on corporations’ capital structure and attempted to ensure the rights of the public, creditors, and shareholders” (Prechel, 2000, p. 26).

Working together, forces, such as the managerial revolution, integration, and technological advancements, provoked the merger movement of the late nineteenth century. As described above with respect to the railroad companies, a wave of consolidations overtook many industries during this time period. According to DuBoff, over 2,653 large-scale businesses vanished in just four years, from 1898 until 1902 (1989). A capitalist economy inspires natural competition within industries, which comes with gains and losses. As the century wore on, competition within industries steepened as new technologies and labor processes were introduced, forcing holding companies to merge with their more efficient competitors, leading to industry monopolies and the rise of big business (ibid.).

For the robber barons of the Gilded Age, the merger movement was clearly beneficial as they gained greater market control. However, Chandler argues that such mergers were rarely profitable until a middle management was added (Chandler, 1977). Their prime responsibility was to plan and oversee the increased number of operations within the newly merged company. Capitalists such as Cornelius Vanderbilt or Andrew Carnegie remained as figureheads for the company, but the day-to-day operations were left to a new level of middle management. This development of the multidivisional structure essentially ended entrepreneurial capitalism, while this new branch of management that resulted from labor reform reshaped production and distribution processes, ensuring the dominance of their company (Chandler, 1977).

Labor Reform

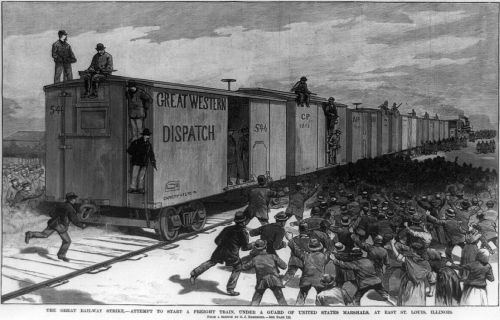

While companies were changing due to external markets, innovation was also needed within the organization. Much of Chandler’s argument on the rise of big business as discussed above relies on correcting the inefficient management and labor techniques. Vertical and horizontal integration led to new managerial hierarchy, which in turn created greater control and less autonomy for workers. These managers, however, were the ones responsible for the shift within the labor markets in the 1870s. During proletarianization, skilled workers and artisans held a great deal of power over the organization. Attempts by management to cut costs by reducing wages were unsuccessful because of this bargaining power. In order to combat this and return the power to the executives, many corporations turned to technology (Gordon et. al, 1982).

The introduction of technology during the late nineteenth century helped to increase short-run efficiency of production by lowering costs and increasing output. However, this was not its primary goal. New technologies were introduced because it lessened the dependence on skilled labor for administrators. At the time, “… workers were being transformed into appendages of machinery itself, which was assuming almost-human attributes as it ‘takes the place of a mere implement’” (DuBoff, 1989, p. 37). This magnifies the division of labor that occurred within the homogenization of the 1870s. Technology helped to deskill the labor, which in turn lessened workers’ bargaining power, restoring it to the hierarchical management.

Similar to how investment led to greater market instability, homogenization led to great labor instability. Employers adopted a divide-andconquer strategy within the workplace to encourage competition between workers and weaken their unity. Through vertical and horizontal integration, employers sought to divide workers through task variability and new job ladders (Gordon et. al, 1982). While unions were productive outlets for negotiations within proletarianization, technology made unionization and bargaining power obsolete. This had a direct result on the workforce, in which “… the union’s prime weapon, the ability to withhold the worker’s labor at peak spring production rushes, had declined because the introduction of machinery made the molders’ skill obsolete” (Gordon et al., 1982, p. 116).

The wave of immigration that occurred in the United States from in the latter half of the eighteenth century furthered homogenization. With various unskilled, ethnically diverse workers flooding American industrial cities, employers found their ideal work group. Manipulating ethnic differences, mangers forestalled assimilation into the workplace and amongst employees. Large industrial firms quickly realized that by exacerbating ethnic and cultural divides they could successfully fracture unionization. Without unions to bargain wages and hours, the labor force essentially lost its control over its employers and was replaced by a culturally divided and unassimilated set of unskilled workers (Gordon et. al., 1982).

As mentioned above, the wave of consolidations simultaneously led to the development of a new level of administration in the form of middle managers. While the emergence of financial corporation facilitated a great portion of mergers, many industrial corporations grew large enough to require middle managers. Responsible for the day-by-day production, these men oversaw market expansion by inventing new techniques to increase production and distribution. For those f irms in an oligopolistic market, they also sought to destroy their competition. At this level, competition was occurring at each stage of production. Therefore, “the success of a firm depended primarily on the caliber of its managerial hierarchy. Such quality in turn reflected the ability of the top executives to select and evaluate their middle managers, to coordinate their work, and to plan and allocate resources for the enterprises as a whole” (Chandler, 1977, p. 413). It is clear for one to see how the not only the rise of middle managers, but also homogenization, shifted the labor power from the workers themselves to the executive management.

As worker control enlarged in the latter part of the century, cost controls were similarly increasing. The implementation of product cost accounting, which measured a firm’s cost of materials, labor, and overhead, left capitalists with the proper information to evaluate and minimize production costs (Prechel, 2000). More specifically, as quoted by Prechel, “…(1) it compared total product costs to market prices for each product, and (2) it directed mangers’ attention toward shop-floor activities to identify and reduce production costs” (Prechel, 2000, p. 97). Although these changes were occurring in the early nineteenth century, the expansion of industry and the managerial revolution furthered the importance of product cost accounting and laid the foundation for corporate finance (ibid).

The Rise of Financial Markets

It is clear to see the influence that the railroads had, especially with respect to investment. Investment quickly became the driving force of economic expansion. DuBoff explains, “… capitalism was evolving toward a strong dependence on private autonomous investment as the prime mover of the economy and investment was becoming the engine of growth and instability” (1989, p. 42). The amount of capital witnessed in the latter nineteenth century was unprecedented. While the accounting procedures in place at many large corporations were effective in the early stages, production soon grew to be managed without formal financial guidance (Prechel, 2000). Private investment banks and the stock market became the primary resources that facilitated the role (ibid). In his book Socializing Capital, William G. Roy focuses of the reflexivity within the relationship between the growth of industry and financial capital markets. Citing what many economists refer to as American’s first big business, the railroads, he highlights how the establishment of railroad corporations was facilitated by increased capital availability through loans, while the growth of the railroad corporations simultaneously furthered growth within financial institutional structures (Roy, 1997). Hugh Rockoff’s paper entitled “Great Fortunes of the Gilded Age” specifically focuses on the returns that many capitalists experienced during this age of expansion. He remarks, “an investment in the stock market at the start of the Gilded Age would have increased, on average, by a factor of nine by the end of the era” (Rockoff, 2008, p. 18) Essentially, these structures became the proponents of their own expansion and of the financial markets.

The railroad industry not only pioneered the merger movement, but it was also the contributed greatly to the emergence the financial markets, especially with respect to its bonds and stock issues. “The stocks and bonds of railroads all over the country began to be listed and actively traded on the New York Stock Exchange as the capital of investors in this country and in Europe was mobilized in support of railways” (DuBoff, 1989, p. 62). The railroad industry’s exponential growth caused financial institutions such as investment banks to begin underwriting and mobilizing financial funds, as well as contributing their own capital. The financial market aided in stabilizing destructive competition, a major concern as discussed above, by overseeing corporate consolidations that enabled firms to have control over prices once again (ibid).

In this time, a direct connection between American industry and investment banks was forming. Banks were expanding outside their commercial limits, including investment banking and stock ownership. The greatest example of this blending between industry and finance can be seen in J. P. Morgan’s financial empire. Morgan was the premier banker during the railroad consolidations, including control over establishing the trust of Vanderbilt’s New York Central Railroad. Morgan, furthermore, serviced the federal government and in the 1890s, a number of prominent life insurance companies, the largest net buyers of corporate securities at the time. While facilitating the trusts within industries such as the railroads, Morgan was simultaneously building his own “money trust” during the evolution of financial markets (DuBoff, 1989).

The Great Robber Baron Fortune

As monopolies and oligopolies became more staple of the American capitalist economy at the end of the nineteenth centuries, the industrial leaders who controlled these companies were simultaneously becoming more prevalent in society. Their mass wealth and influence created a shift toward plutocracy (Cashman, 1984). John Reagan, a congressman from Texas at the time, furthers this by saying, “There were no beggars till Vanderbilts and Stewarts and Goulds and Scotts and Huntingtons and Fisks shaped the action of Congress and molded the purposed of government. Then the few became fabulously rich, the many wretchedly poor… and the poorer we are the poorer they would make us” (Cashman, 1984, p. 51). While these robber barons were reaping the rewards of the rise of big business, the general American was suffering due to many of the reforms explained during labor reform, in turn producing rising inequality (Rockoff, 2008). Relying on a macroeconomic framework, Rockoff’s concluding argument within his paper “Great Fortunes of the Gilded Age” rests on four factors of the economy that allowed entrepreneurs of the late nineteenth century to amass such wealth.

The first, relying on Chandler’s argument on the necessity for firms for vertically integrated, explains how while the introduction of new technology allowed for short-run efficiency and lower costs for management, there was also a great deal of exploitation by the robber barons that led to their accumulation of wealth. He explains, “It often took… ruthless ambition and a willingness to break moral and legal constraints to succeed in exploiting the advantages created by new manufacturing technology” (Rockoff, 2008, p. 27). This quote mirrors one earlier discussed by DuBoff with respect to the Standard Oil Company’s relentless expansion (DuBoff, 1989).

The argument continues to state that the economy of the Gilded Age was favorable to robber barons, specifically in terms of property rights and taxes. The property laws of the time were strongly protected, therefore allowing one to purchase and develop land across the country or even foreign investors from owning land in the United States. This increased capital flow from overseas simultaneously increased the amount of American millionaires. Perhaps the influential factor that allowed for the robber barons to amass so much fortune was the lack of federal income tax. The income tax that was enacted during the Civil War dissolved in 1872 and did not return until 1913. By this time, the ability to reinvest all returns earned during investments without the any loss due to taxes greatly impacted their savings and ultimately, led to the widening income distribution that Rockoff uses as his last point (Rockoff, 2008).

Not only did the lack of an income tax allow for rising income inequality but further, a shift from an agrarian economy to one of industry also impacts the distribution of wealth. Rockoff argues that the urbanization that is a direct result of the industrial revolution produced increasingly skewed wealth. He is quoted as saying, “In our list of millionaires, we can see a particularly straight channel from urbanization to wealth inequality” (Rockoff, 2008, p. 28). Therefore, one can plainly see how the industrial robber barons of the late nineteenth century produced inequalities that our economy still battles today.

The Standard Oil Company: A Case Study

Thus far, this paper has sought to examine transformation of industry from family-oriented firms to large-scale monopolies and oligopolies, in which robber barons controlled their own respective industry as well as the majority of wealth and governmental power. One specific example of this is The Standard Oil Company, a predominant oil refining company under the control of John D. Rockefeller. DuBoff describes the company as one that “… became the image of relentless expansion by any means it took to discipline an unruly industry and achieve satisfactory control over prices and output” (DuBoff, 1989, p. 48). The question of this case study becomes how did Rockefeller transform his company into one of the most successful trusts of its time?

John D. Rockefeller’s began his entrepreneurial career in oil production the 1860s. According to Cashman, he achieved success through four stages. “Initial establishment of his own companies between 1862 and 1870; manipulation of transportation for his own advantage; ruthless elimination of competition; and an interlocking trust to unify his empire” (Cashman, 1984, p. 54). This empire first began in Cleveland, Ohio, but would expand to include refineries in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York (Tedlow, 1991). Following fellow robber baron Andrew Carnegie’s philosophy to “put all your good eggs in one basket and then watch that basket”, Rockefeller made large-scale investments through the growing financial markets that allowed him to gain economies of scale in which he constructed his monopoly (ibid.).

Establishing a new partnership with Henry M. Flager, increased capital pushed further expansion into the Standard Oil Company. The official formation of the Standard Oil Trust occurred in January of 1882. Unlike with a cartel or trade association, the trust allowed Rockefeller and his subordinates to control multiple subsidiaries across the country (Chandler, 1977). In 1866, a second refinery was constructed in Cleveland and by 1869, the company was producing 1,500 barrels of oil per day, triple what they produced just four years prior (Tedlow, 1991). The sheer size and skill of Rockefeller’s refineries forced the unit cost to drop. “This relationship of scale to costs has remained central to the structure of the oil industry from that date to this. Thus, because Rockefeller’s Cleveland refinery complex had become the largest in the industry, it also became its low-cost producer,” Chandler explains (Tedlow, 1991, p. 34).

While unit costs may have plummeted, transportation costs were still increasing, reaching $2.00 per barrel of oil from Cleveland to New York in 1870. Rockefeller, however, was able to negotiate a 35% decrease in rates to $1.30 per barrel in exchange for supplying 60 carloads of kerosene per day (Tedlow, 1991). As discussed above with respect to the growth of financial markets, the use of accounting procedures allowed Rockefeller to closely monitor his production and distribution costs and in turn, lower them (Chandler, 1977). The railroads had grown just as dependent on the oil industry as the oil industry was on the railroads. With such low costs and high output, Rockefeller quickly conquered the Cleveland market and expanded into other refineries. Already controlling transportation, he sought to gain control over his competitors and supplies through the Standard Oil “alliance”, trading Standard Oil stock for the assets of the competing firm. By 1880, there were 40 firms in the alliance and Standard Oil was controlling more than 90% of the market (Tedlow, 1991).

Rockefeller’s foresight into the future had not only led the company to domestic domination, but furthermore, internationally. Rockefeller had international ambitions since the beginning of his company. By 1888, these ambitions were becoming reality as the company introduced a fleet of companyowned steam tankers in the Atlantic. Subsidiaries, whether wholly or partially owned, were established throughout Europe by the 1890s, allowing for domination of the oil industry well into the 1920s (Tedlow, 1991).

The success of The Standard Oil Company rested in John D. Rockefeller’s ability to read his competition and inefficiency. Constantly improving his own f irm, Rockefeller was closing smaller, inefficient refineries in favor of building larger, more productive ones into the turn of the century (Tedlow, 1991). His rationalization of production allowed him to gain economies of scale, lower unit costs, and eventually, reap the profits. Other attributes such as a steady supply of raw materials, and investment in technology and research and development, allowed Rockefeller, and so many of his capitalist peers, to transform an unknown company, in which he contributed $2,000 of capital, into a multi-million dollar global monopoly (Tedlow, 1991).

Conclusion

The expansion that occurred in the latter half of the nineteenth century transgressed not only within the industrial sector, but also into the labor and f inancial markets. Large-scale manufacturing due to new technological advances led to a wave of consolidations and hierarchical management reform, leaving the most successful firms of the period in a monopolistic and oligopolistic economy with unprecedented amounts of capital. Case studies, such as J. P. Morgan and the Standard Oil Company, highlight the control of industry, government, and wealth held by these industrial giants. While the innovation seen in The Gilded Age resulted in massive growth in output and capital, eventually causing the rise of big business and finance, it can also be remembered as a time of a divided workforce and rising inequality.

References

- Cashman, Sean Dennis (1984) America in the Gilded Age: From the Death of Lincoln to the Rise of Theodore Roosevelt. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Chandler, Alfred D (1977) The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- DuBoff, Richard B. (1989) Accumulation and Power: An Economic History of the United States. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- Gordon, David M., Edwards, Richard and Reich, Michael (1982) Segmented Work, Divided Workers: The Historical Transformation of Labor in the United States. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Prechel, Harland (2000) Big Business and the State: Historical Transitions and Corporate Transformation, 1880s-1990s. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Rockoff, Hugh (2008) “Great Fortunes of the Gilded Age.” NBER Working Paper 14555. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Roy, William G. (1997) Socializing Capital. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Tedlow, Richard S. (1991) The Rise of the American Business Corporation. New York, NY: Harwood Academic Publishers.

Originally published by The Gettysburg Economic Review 5:6 (2012) under the terms of an Open Access license.