“Santa Anna’s personal life mirrored the opportunism and self-interest that characterized his political career.”

By Ray Scheel, M.Ed.

Senior Education Leader

Online Learning Strategist

Educational Project Management

Introduction

On this 189th anniversary of the Battle of San Jacinto (April 21, 1836), we reflect on a pivotal event that not only shaped Texas but epitomized the broader Mexican resistance against Antonio López de Santa Anna’s centralist regime.. The Battle of San Jacinto was not an isolated incident but part of a larger tapestry of resistance against Santa Anna’s centralist policies, which sought to dismantle Mexico’s federalist constitution and consolidate power.

Once a charismatic president, Santa Anna’s dismantling of Mexico’s federalist constitution through the 1834 Plan de Cuernavaca was ostensibly aimed at restoring order. However, it fundamentally served to protect traditional elite power structures against federalist reforms. Measures like the 1833 Ley del Caso, which expelled politicians deemed ‘unpatriotic,’ exemplified his strategy to suppress dissent and consolidate his authority.

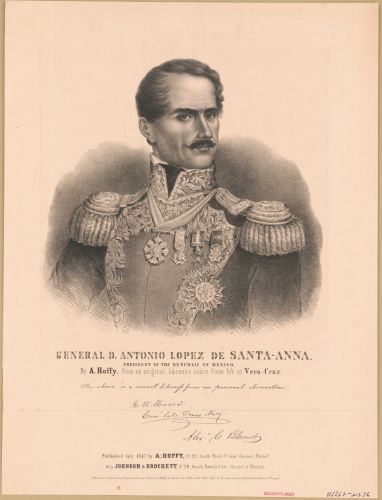

Early Life and Rise to Power

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (1794-1876) was born in Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico into a middle-class Creole family. Though receiving some formal education, he was largely self-taught. Joining the Spanish army at 16, he rose through the ranks. During the Mexican War of Independence, he initially sided with Spain before switching allegiance to the independence movement—an early sign of the political opportunism of the rising caudillo (the political-military strongman common in 19th-century Latin America, and still an archetype today) that would define his career and lead to him being considered “vendepatria” (a sellout) by many in Mexico to this day. His military acumen and charisma propelled him to prominence in the turbulent early years of the Mexican Republic, where he was eventually officially named president five or six times, and temporarily took the position by force or influence enough to have been president eleven times.

Personal Life and Character

Santa Anna’s personal life, marked by controversial marriages and numerous affairs, mirrored the opportunism and self-interest that characterized his political career. His marriages to very young women from wealthy families for financial gain and his numerous affairs highlight a pattern of prioritizing personal gratification over societal norms. He married twice, both times to very young women from wealthy families, in matches that were primarily for financial gain: Maria Ines de la Paz Garcia in 1825 (aged 14) and Maria Dolores Tosta in 1844 (aged 15), proposing to the latter less than a month (and marrying her just 40 days) after his first wife’s death. He was notably absent from both wedding ceremonies. These arranged unions starkly contrasted with his numerous affairs and acknowledged illegitimate children. Some accounts, though debated, even suggest a sham marriage following the Battle of the Alamo in order to complete the seduction of a girl he wished to take advantage of. He eventually cared better for Tosta (or rather, she was using her family money and influence to take care of him after he fully fell from power and was no longer such a dashing figure as he aged). This pattern of prioritizing personal gratification and financial gain, often at the expense of others and societal norms, arguably mirrored his approach to governance and national interest, and highlights a character driven by self-interest and a disregard for convention or promises made.

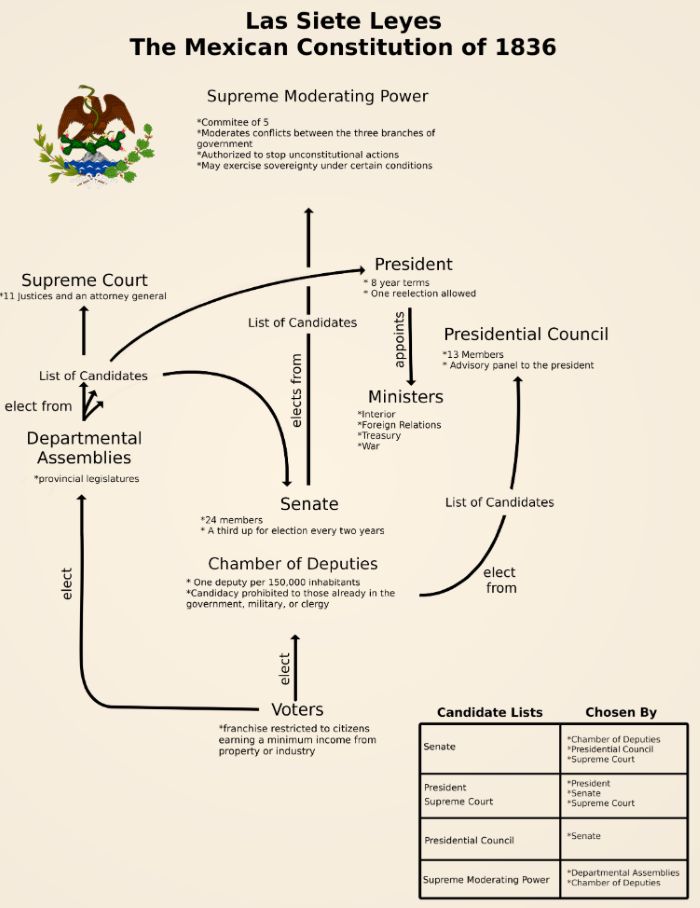

The Turn to Centralism and Rebellion

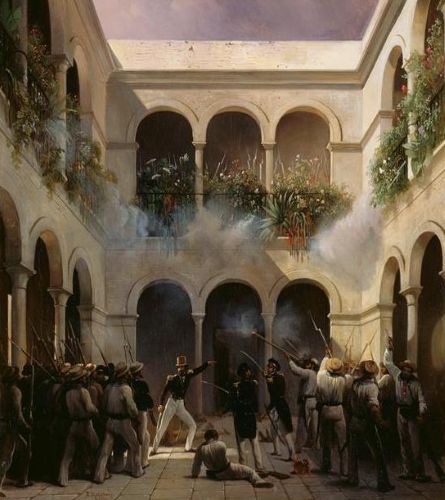

Santa Anna’s consolidation of power culminated in the repeal of the federalist republic ideals of 1824 Constitution (with states’ rights modeled after the US Constitution) and the implementation of Las Siete Leyes (The Seven Laws) in 1836. This fundamentally altered Mexico’s governance, replacing the federal republic with a centralized system where states became departments controlled from Mexico City. This concentration of power, intended to create stability, instead fueled widespread resistance as states lost their autonomy. Rebellions erupted across Mexico, including in Alta California, Nuevo México, Yucatán, Zacatecas, and Coahuila y Tejas. Santa Anna brutally crushed the well equipped Zacatecas militia in May 1835 after only two hours of combat, allowing his troops to loot the city for two days. He then turned his attention to Coahuila y Tejas, assembling a hastily organized army that included conscripts and convicts, as well as Native Americans who could not understand Spanish, and a wholly insufficient supply chain.

The Texas Revolution and Brutality

Santa Anna’s approach to the Texas Revolution, marked by brutal tactics and strategic miscalculations, exemplified his leadership flaws. His “no quarter” order at the Battle of the Alamo (March 6, 1836), which resulted in the deaths of nearly all defenders, followed by the execution of over 340 captured Texian soldiers at the Goliad Massacre (March 27, 1836), exemplified his brutality and strategic blunders, actions widely condemned even by contemporary standards of warfare. Far from crushing the rebellion, these atrocities galvanized the Texian forces. The battle cry, “Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!” fueled their decisive victory at the Battle of San Jacinto, where Santa Anna himself was captured (and leading to his first period of exile). This defeat underscored his tendency towards rash actions driven by pride and a failure to understand the opposition he created.

Flawed Leadership: Style and Substance

The elaborate uniforms and costly ceremonies favored by “His Serene Highness” Santa Anna showcased a leadership style marked by a preference for spectacle over substance and impulsive decision-making. He frequently relied on military force rather than diplomacy, aggravating internal conflicts. Although repeatedly chosen to lead (or taking power by force), he often retreated to one of his many haciendas, delegating governance to others while he recuperated or led campaigns. This inconsistent presence disrupted policy continuity, eroded public confidence, and weakened the executive branch’s ability to address Mexico’s deep-seated challenges. His approach left Mexico fragmented and ill-prepared for external threats.

Corruption and Cronyism

His administration was rife with corruption. Santa Anna granted lucrative concessions to allies, diverted state funds for personal use, and secured favorable deals for his inner circle. This culture of cronyism and exploitation stemmed directly from the self-serving priorities evident throughout his career, undermined trust in government, destabilized the economy, discouraged investment, and arguably damaged Mexico’s future ability to function as a solvent nation as much as its territorial losses.

Foreign Policy Failures and Territorial Losses

Santa Anna’s poor handling of international relations, characterized by bravado and miscalculation, led to disastrous consequences. His actions during the Texas Revolution and later the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) resulted in Mexico losing vast territories. Facing mounting debts and internal strife, his government resorted to controversial land deals, ceding significant land (what is now much of the Southwestern United States) in exchange for short-term financial relief. These decisions, driven by desperation and culminating in deals like the Gadsden Purchase (1854), represented a profound loss of national potential. The ceded territories evolved into economically powerful regions, highlighting the immense long-term cost of Santa Anna’s shortsighted policies.

Enduring Legacy

Santa Anna’s legacy is defined by failed leadership, characterized by charisma overshadowed by multiple missed opportunities and short-term gains. His pursuit of personal power, shift to centralism, military brutality, inconsistent governance, corruption, and foreign policy failures inflicted lasting damage on Mexico, contributing to enduring political instability and economic challenges. The internal strife, economic instability, and massive territorial losses weakened the nation significantly. It raises enduring questions about political accountability and the moments when a nation might have altered its trajectory.

Antonio López de Santa Anna died in relative obscurity in 1876 in Mexico City, two years after an amnesty allowed his return from exile in Cuba. His name remains synonymous with the loss of half of Mexico’s territory and the turbulent, damaging era he presided over, leaving a legacy of political instability and economic challenges that continue to echo through Mexican history.

Bibliography

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonio_L%C3%B3pez_de_Santa_Anna

- https://exhibits.lib.utexas.edu/spotlight/santa-anna-in-life-and-legend/feature/his-serene-highness-and-the-absentee-president

- https://officialalamo.medium.com/the-return-to-centralism-66cf9b32547c

- http://www.sonofthesouth.net/texas/first-revolutionary-movement.htm

- https://www.infobae.com/america/mexico/2022/05/21/quienes-fueron-los-grandes-amores-de-santa-anna-el-gran-villano-de-la-historia/

- https://www.infobae.com/america/mexico/2022/04/01/santa-anna-cuantas-veces-estuvo-en-el-poder-el-presidente-que-perdio-la-mitad-del-territorio-mexicano/

Originally published by Brewminate, 04.21.2024, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.