Pseudoscientific claims are often untestable or tested only in non-rigorous, anecdotal ways.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Defining Pseudoscience

Overview

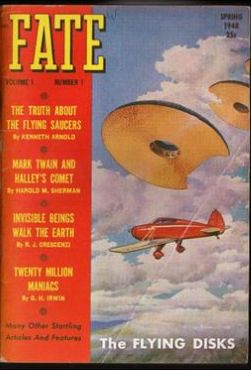

In a world flooded with data and permeated by claims of knowledge, distinguishing between science and pseudoscience has become more vital—and more difficult—than ever before. The term “pseudoscience” conjures images of astrologers, conspiracy theorists, and snake oil salesmen, but its history is far older and more complex. From ancient augurs to modern influencers peddling dubious health supplements, pseudoscience has shadowed legitimate inquiry, often borrowing the language and symbols of science while denying its rigor and methods.

Etymology

The term pseudoscience is a linguistic hybrid, combining the Greek prefix pseudo- (ψευδής), meaning “false” or “deceptive,” with the Latin word scientia, meaning “knowledge.” It first appeared in print in the early 19th century, though the phenomenon it describes long predates the word itself. The earliest known usage of the term dates to 1796 in the work of the French physiologist François Magendie, who criticized speculative systems that lacked empirical grounding. The term gained wider circulation in the mid-19th century, particularly as the scientific revolution matured into more formal institutional structures and sought to separate itself from mystical or metaphysical systems. Its hybrid linguistic roots reflect an epistemological conflict—between knowledge grounded in empirical methods and frameworks masquerading as such to claim undeserved legitimacy.

Pseudoscience is often defined not by the presence of false claims per se—science itself is constantly revised and sometimes wrong—but by the absence of methodological rigor and falsifiability. The philosopher Karl Popper famously proposed falsifiability as the key demarcation criterion between science and pseudoscience. According to Popper, scientific theories must be structured in such a way that they can be proven wrong through observation or experiment; pseudoscientific claims, by contrast, are often constructed to be immune to disproof. For example, the claim that all outcomes support a theory—regardless of whether they align with predicted results—signals a retreat from falsifiability into the realm of dogma. Thus, while the term pseudoscience carries a pejorative connotation, it also serves as a philosophical tool for classifying forms of inquiry according to their relationship with empirical evidence and self-correction.

Conceptually, pseudoscience thrives in a gray zone between knowledge and belief. It often borrows the visual language, terminology, and rhetorical strategies of science to gain cultural legitimacy. Charts, formulas, lab coats, and citations may all be used to lend an air of authority to ideas that have not undergone proper peer review or experimental validation. This mimicry is part of what makes pseudoscience so culturally resilient. It exploits the epistemic trust that modern societies place in scientific institutions while circumventing the actual disciplinary norms that undergird those institutions. From astrology’s use of astronomical terms to phrenology’s cranial measurements, pseudoscientific systems often create an illusion of rigor that masks their speculative or ideologically driven foundations.

Another defining feature of pseudoscience is its resistance to change. Where science evolves through the accumulation of evidence, and ideas can be abandoned or revised in light of new data, pseudoscientific systems are typically inflexible. They often rely on confirmation bias, anecdotal evidence, and appeals to authority rather than reproducible results. This ideological fixity serves a psychological function: it provides adherents with certainty, coherence, and often a sense of purpose that science’s provisional nature may lack. In this way, pseudoscience operates not merely as faulty reasoning but as a cultural and emotional phenomenon—a belief system rather than a method of discovery. It offers a closed worldview, frequently imbued with moral or metaphysical implications that extend beyond empirical claims.

Finally, the label pseudoscience itself has become contested, both philosophically and politically. Critics have argued that it can be wielded too liberally, used to silence unconventional theories before they are fully explored or understood. Others point out that historically, some now-legitimate scientific ideas (such as plate tectonics or heliocentrism) were once dismissed as pseudoscientific. Yet while these critiques caution against epistemic authoritarianism, they do not invalidate the concept of pseudoscience as a useful heuristic. The challenge lies in applying the term with intellectual integrity, recognizing that the history of science includes both the suppression of innovative ideas and the proliferation of charlatanism. As such, the concept of pseudoscience remains central to understanding the boundaries of credible inquiry in both historical and contemporary contexts.

One of the most enduring and debated problems in the philosophy of science is the demarcation problem—how to distinguish genuine scientific inquiry from pseudoscientific imitation. While there is no universally accepted checklist, several criteria have been proposed by philosophers and historians to help mark this boundary. Chief among them is the presence of a systematic method, especially the scientific method, which emphasizes observation, hypothesis formation, experimentation, and replication. In science, claims are tested against reality through controlled observation or experimentation, and they must withstand scrutiny from a community of peers. Pseudoscience, by contrast, tends to lack this systematic approach. Its claims are often untestable or tested only in non-rigorous, anecdotal ways that are not subject to replication or independent verification. Thus, method and the attitude toward evidence are fundamental to the distinction.

Falsifiability, introduced by Karl Popper, remains one of the most cited criteria in demarcation discourse. A scientific theory must be structured so that it could, in principle, be proven false. This does not mean the theory is necessarily false, but rather that it exposes itself to the risk of refutation by empirical data. Pseudoscientific claims often avoid this vulnerability by being framed in ways that are vague, unfalsifiable, or self-confirming. For instance, many alternative medical practices claim to work through “energy fields” or “vibrations” that cannot be measured, observed, or defined in precise terms, making them immune to disproof. Such claims may persist unchanged even in the face of contradictory evidence, which starkly contrasts with the self-correcting nature of science, where a single robust counterexample can prompt a paradigm shift.

Another distinguishing criterion is peer review and openness to critique. Scientific research is embedded in a community of practice that includes mechanisms for evaluating, correcting, and building upon findings. Peer-reviewed journals, academic conferences, and institutional protocols serve to filter out flawed research and ensure transparency in methods and data. Pseudoscience tends to operate outside or on the fringes of this ecosystem, often preferring self-published materials, mass media platforms, or populist appeal over institutional engagement. When faced with criticism, pseudoscientific proponents frequently respond with ad hominem attacks or appeals to persecution rather than addressing the substantive flaws in their arguments. This resistance to critical engagement reveals an epistemic insulation that is antithetical to scientific inquiry.

Empirical adequacy and predictive power are also essential criteria. Scientific theories are expected to make predictions that can be verified under specific conditions and to account for a broad range of phenomena without excessive reliance on ad hoc hypotheses. A hallmark of pseudoscience is its tendency to introduce new, often untestable assumptions whenever its predictions fail, rather than revising the core theory. For example, proponents of astrology might explain away failed horoscopes by invoking unseen influences or improperly timed readings, rather than acknowledging flaws in the underlying framework. The use of ad hoc rationalizations prevents theories from evolving meaningfully and often results in the entrenchment of belief rather than the expansion of knowledge.

Lastly, consistency with existing knowledge and conceptual coherence are important indicators. While revolutionary scientific ideas may sometimes challenge existing paradigms, they generally do so in ways that are logically consistent and eventually integrated with broader scientific understanding. Pseudoscience often lacks this coherence, instead creating compartmentalized belief systems that contradict established physical laws or biological principles. Furthermore, scientific progress is cumulative; it builds on prior work and deepens our understanding of the world. Pseudoscience, on the other hand, tends to be stagnant or cyclical, recycling ideas that have already been discredited or disproven. In this way, science is characterized by dynamism and intellectual humility, while pseudoscience is marked by rigidity and an often overconfident certainty in unproven claims.

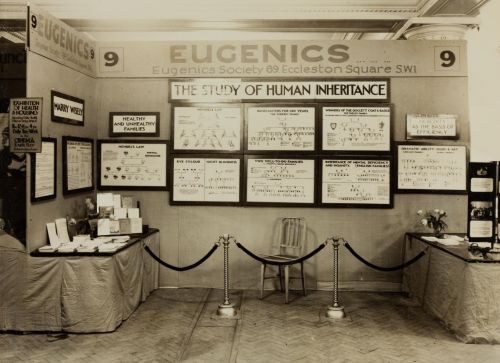

Pseudoscience matters because it has profound implications not only for individual belief systems but also for public policy, education, health, and democracy. While it may seem benign when limited to personal practices—such as reading horoscopes or wearing crystals—pseudoscientific beliefs can shape decisions with far-reaching consequences. In the realm of health, for example, the promotion of pseudoscientific treatments over evidence-based medicine has led to vaccine hesitancy, the rejection of life-saving treatments, and the embrace of dangerous “cures” for serious illnesses. During global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, pseudoscientific misinformation undermined public health efforts, fueled conspiracy theories, and resulted in avoidable deaths. In the political sphere, pseudoscientific ideologies like eugenics, racial pseudoscience, and climate change denial have influenced policies that perpetuate inequality and environmental degradation. Thus, pseudoscience is not just a matter of intellectual error—it is often an active force that can misdirect resources, foster social divisions, and erode trust in legitimate scientific institutions.

Moreover, pseudoscience challenges the foundations of critical thinking and scientific literacy that are essential to functioning societies. In an age where information is abundant but not always credible, the ability to distinguish between reliable and unreliable knowledge is vital. Pseudoscientific ideas often flourish in environments where scientific literacy is low and emotional appeal outweighs rational inquiry. They offer simple answers to complex questions, a sense of certainty in uncertain times, and community for those who feel marginalized or alienated from academic or governmental authority. While these functions help explain pseudoscience’s psychological appeal, they also make it resistant to correction and self-reflection. This epistemic closure—where beliefs are insulated from evidence and immune to challenge—threatens the ideals of open inquiry and democratic deliberation. In this way, combating pseudoscience is not simply a scientific or educational challenge, but a cultural and civic one, requiring sustained engagement across multiple domains of public life.

Pseudoscience in the Ancient World

Reading the Stars in Ancient Babylon

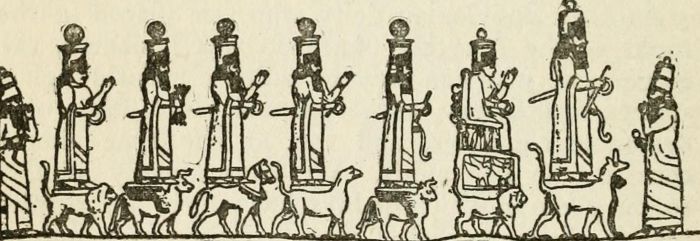

Ancient Babylonian astrology represents one of the earliest known systems in which celestial observation was systematically linked to terrestrial events. Originating in Mesopotamia, particularly in the region corresponding to modern-day Iraq, Babylonian astrology was deeply embedded in religious, political, and cosmological frameworks. As early as the second millennium BCE, Babylonian scholars—often priest-astronomers known as ṭupšarru—began to document the regular motions of celestial bodies and interpret their significance. Their efforts gave rise to a vast and sophisticated body of omen literature, notably the Enuma Anu Enlil, a compilation of around 7,000 omens concerning planetary movements, eclipses, lunar phases, and meteorological phenomena. This corpus formed the foundation for divinatory practices that would persist for centuries and later influence both Greco-Roman and Islamic astrology.

The Babylonian approach to astrology was fundamentally omenic rather than personal. Unlike later Greek and modern astrological traditions that focused on individual horoscopes, Babylonian astrology was primarily concerned with the fate of the king, the wellbeing of the state, and the cyclical patterns of nature. Celestial phenomena were interpreted as messages from the gods, particularly Anu (god of the heavens), Enlil (god of the air and storms), and Ea (god of wisdom), who were believed to communicate their will through the skies. When Jupiter was in a certain position, or when a lunar eclipse occurred in a specific month, it was seen not as a natural event, but as a sign of divine favor or wrath. These interpretations were not arbitrary; they were recorded over centuries and correlated with political and natural events, creating a proto-empirical body of predictive material.

Astrological omens in Babylonian culture were part of a broader divinatory tradition that included hepatoscopy (reading sheep livers), dream interpretation, and the reading of terrestrial omens like the behavior of animals or abnormalities in childbirth. Astrology, however, held a particularly prestigious place because of its association with the heavens, which were seen as a divine realm of order. The Babylonians were meticulous observers of the sky, and over time developed methods to predict eclipses and the periodic appearance of planets. Their mathematical astronomy became increasingly advanced by the first millennium BCE, culminating in the ability to forecast celestial events with remarkable precision using arithmetic schemes. Yet, despite this scientific sophistication, the interpretive framework remained theological and symbolic, not empirical in the modern sense.

One of the defining characteristics of Babylonian astrology was its reliance on precedent. The idea was that if a certain celestial configuration had previously occurred in conjunction with a specific event—such as a war, flood, or dynastic upheaval—then the reoccurrence of that configuration would herald a similar outcome. This “if A, then B” logic pervaded the omen texts and reveals a core feature of pseudoscientific thinking: the conflation of correlation with causation. Babylonian astrologers did not test hypotheses or subject their interpretations to falsification; rather, they compiled increasingly elaborate records that supported divinatory patterns retrospectively. This reliance on analogy over systematic causality contributed to the enduring appeal of the system, but also limited its potential for scientific evolution.

Despite its pseudoscientific interpretive structure, Babylonian astrology must be understood within the context of its time. The distinction between science, religion, and magic was not present in the ancient Near East as it is today. Priest-scholars were both astronomers and diviners, theologians and mathematicians. Their observations contributed to real advances in astronomy, timekeeping, and calendar reform. The accurate tracking of the lunar cycle, the solar year, and planetary periods were essential for agricultural planning, religious festivals, and royal omens. In this sense, astrology acted as a bridge between practical knowledge and metaphysical speculation—a blend of what we would now call proto-science and spiritual belief. This complexity resists simplistic dismissal and requires historical sensitivity.

By the 5th century BCE, Babylonian astrologers began constructing birth charts based on the positions of celestial bodies at the time of an individual’s birth. This innovation marked the beginning of natal astrology, a practice that would be adopted and further elaborated by the Greeks and Romans. These early horoscopes were reserved for elite individuals—often royalty—and still largely interpreted in political or dynastic terms. However, the conceptual leap from interpreting omens for the state to interpreting them for individuals reflected a significant shift in the role astrology played in society. It foreshadowed the personal horoscopic systems that would dominate later astrological traditions and expand astrology’s reach beyond the court into the private lives of ordinary people.

The intellectual prestige of Babylonian astrology also ensured its transmission and adaptation by neighboring cultures. During the Achaemenid Persian period (6th–4th centuries BCE), Babylonian astrologers served in the imperial bureaucracy and helped spread Mesopotamian astrological techniques across the empire. With the conquests of Alexander the Great, Greek scholars encountered this Mesopotamian knowledge and began synthesizing it with their own cosmological models. The result was the Hellenistic astrological tradition, centered in Alexandria, which combined Babylonian celestial omens, Egyptian decanal systems, and Greek philosophical concepts such as the four elements and planetary temperaments. This cross-cultural synthesis gave astrology a new intellectual framework and helped sustain its influence well into the medieval period.

Babylonian astrology also played a significant role in legitimizing political power. Kings routinely consulted astrologers before military campaigns or major decisions. Astrological omens could be used to justify or postpone wars, anoint successors, or explain the misfortunes of a ruler. In times of negative omens, Babylonian kings would sometimes install a “substitute king” (a šar pūhi)—a temporary figurehead meant to absorb divine wrath—until the danger had passed. This ritual, known as the substitute king ritual, highlights how astrology was not merely predictive but performative: it shaped reality through the enactment of belief. Such practices underscore how deeply embedded astrological systems were in the political and ritual life of Mesopotamia.

From a modern perspective, Babylonian astrology is typically categorized as a form of pseudoscience because it lacks testability, falsifiability, and causal explanation. However, this classification should not obscure its historical significance or intellectual complexity. While the interpretive content of astrology was symbolic and theological, its development required rigorous observational astronomy and a deep commitment to long-term data collection. The Babylonians were among the first civilizations to conceptualize time and motion in mathematically structured ways, and their records laid essential groundwork for later scientific astronomy. This paradox—advanced observational technique embedded in a divinatory framework—is emblematic of how pseudoscientific systems often co-exist with genuine empirical practices in the early history of knowledge.

Babylonian astrology illustrates the entangled roots of science and pseudoscience. It reveals how human beings, long before the modern scientific method, sought to find order and meaning in the universe through systematic observation of nature. Their efforts were constrained by theological assumptions and interpretive traditions that today would be considered non-scientific, yet they nonetheless contributed significantly to the intellectual infrastructure of ancient and medieval civilizations. By studying Babylonian astrology not merely as an error of belief but as a cultural system embedded in its time, we gain insight into the complex motivations—political, psychological, spiritual—that drive human beings to seek patterns in the stars, and to find in those patterns a reflection of their own fate.

Egyptian Medicine and Magic

Ancient Egyptian medicine, while rooted in practical knowledge of anatomy and disease, was inextricably linked to religious and magical beliefs. The ancient Egyptians believed that health was the result of harmony between the body and the gods, and that illness was caused by the interference of malevolent spiritual forces. This worldview shaped their approach to medicine, where physical treatments and magical rituals often went hand in hand. Egyptian medicine was deeply intertwined with religious practices, and healing was often seen as the work of gods, with physicians considered intermediaries who invoked divine aid to cure illness. This dual nature of healing—employing both practical remedies and magical interventions—made Egyptian medicine unique in the ancient world, where magic was regarded as a fundamental force influencing all aspects of existence.

One of the central figures in Egyptian medicine was Imhotep, the legendary vizier of the Third Dynasty Pharaoh Djoser, who became deified after his death. Imhotep was revered as the god of healing and medicine, and his legacy is a testament to the syncretism between medicine and magic in ancient Egypt. He was often depicted as a wise, rational healer who combined empirical medical knowledge with divine influence. His contributions to the development of medical texts and the practice of medicine in Egypt were substantial, and his divine status as the patron of physicians underscored the belief that the act of healing required divine sanction. In fact, many of the medical practitioners in Egypt were also priests, and their role was as much about mediating between the human and divine realms as it was about diagnosing and treating physical ailments.

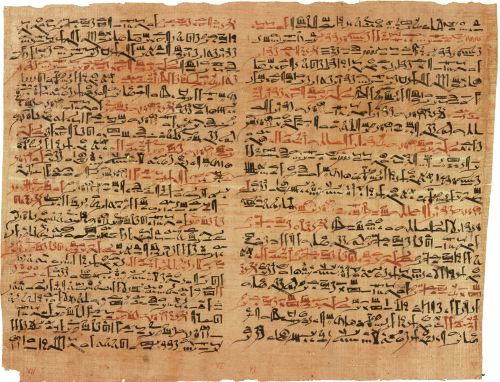

Egyptian medical knowledge was codified in a series of texts, including the Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE) and the Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 1600 BCE), both of which contain detailed accounts of diseases, treatments, and surgical techniques. The Ebers Papyrus is particularly notable for its extensive list of remedies for various ailments, many of which were rooted in herbal medicine. This includes treatments for skin conditions, gastrointestinal problems, and even heart disease. The Edwin Smith Papyrus is a surgical text that describes methods for treating wounds, fractures, and dislocations, indicating that the Egyptians possessed a relatively advanced understanding of human anatomy and trauma care. Despite the prevalence of empirical remedies, however, these texts also contain spells and incantations to aid in healing, illustrating the seamless integration of medical and magical practices.

Magic in ancient Egyptian medicine was not only used to treat illness but was also invoked to ward off evil spirits, protect the body, and ensure fertility. The Egyptians believed that illness could be caused by spiritual imbalance, curses, or angry gods, and thus healing required more than just physical remedies—it demanded a spiritual cure. One common magical practice involved the use of amulets, which were inscribed with protective spells and worn by patients. These amulets were believed to protect the wearer from disease and evil influences. The practice of placing the body in a protective cocoon of magic was evident in the embalming process, where the dead were surrounded by spells meant to ensure their safe passage into the afterlife and to protect their bodies from decay.

In addition to amulets, spells were an essential component of Egyptian medical practice. The Book of the Dead, a funerary text, included numerous magical incantations designed to protect the deceased from harmful spirits and guarantee safe passage to the afterlife. These spells were often recited by priests or healers who had specialized knowledge of the sacred texts. The connection between words, magic, and healing was deeply ingrained in Egyptian thought; the spoken word was seen as a powerful force capable of influencing the gods and nature. Thus, healing in ancient Egypt often involved not only physical treatments but also ritual recitations to invoke divine protection and intervention.

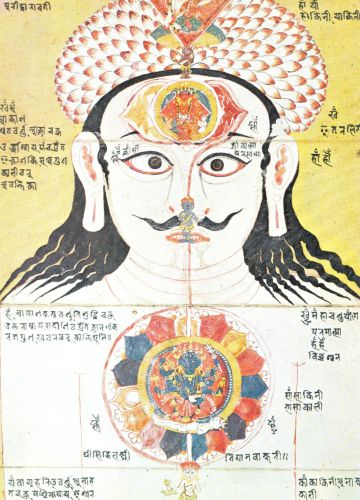

The Egyptian approach to medicine was also influenced by their understanding of the body and the forces of nature. The concept of the ka, a life force or spiritual essence that existed in every person, was central to their medical and magical worldview. Illness was often seen as an imbalance in the ka, and healing required restoring harmony between the body, spirit, and the gods. To maintain this balance, Egyptians practiced rituals that were intended to align the individual with cosmic forces, including the natural rhythms of the Nile River, the sun, and the stars. The close relationship between the physical body and the spiritual realm reflected the holistic nature of Egyptian healing, where both physical treatments and spiritual purification were required for true health.

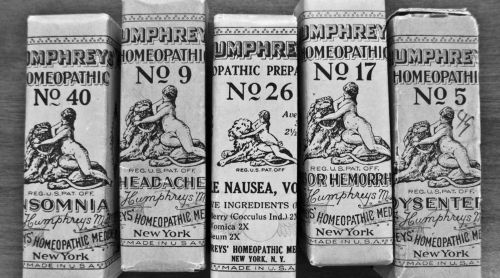

Another aspect of Egyptian medicine was its close relationship with the practice of homeopathy, which is the idea that “like cures like.” Egyptians believed that certain substances contained inherent magical properties, and that by consuming or applying them, one could restore balance to the body. For example, they used honey and resins, not only for their medicinal properties but also for their symbolic and magical qualities. Honey, for instance, was seen as a substance favored by the gods, and it was commonly used to treat wounds due to its antiseptic properties. Similarly, plants and minerals were often used in both a medicinal and magical context, such as the use of the mandrake root, which was believed to have magical properties that could cure infertility and promote healing.

Ancient Egyptian physicians were highly skilled in treating various conditions, from dental problems to eye diseases, and they utilized a wide array of treatments, including surgery, bandaging, and splinting. The Ebers Papyrus contains references to surgical tools, some of which resemble those used in modern medicine, indicating that Egyptians had a certain level of surgical expertise. However, the spiritual aspects of healing remained central to their practice. For instance, cataract surgery, which was performed by skilled Egyptian doctors, involved both medical intervention and incantations. The healer would recite specific spells during the procedure, believing that the gods would aid in the healing process and that the patient’s soul would be restored along with their physical health.

Despite the highly ritualized nature of Egyptian medicine, the Egyptians did make significant contributions to medical knowledge that were based on observation and empirical evidence. Their understanding of anatomy, based largely on their experience with embalming the dead, was fairly advanced for the time. They had a clear understanding of the circulatory system, and there are records of them performing surgeries to drain abscesses or treat fractures. However, these advances were always interwoven with magical beliefs. A physician might diagnose a patient’s condition through observation and clinical judgment but would also recite prayers and perform rituals to ensure the patient’s recovery. This blending of practical and magical elements made Egyptian medicine unique in the ancient world, marking a fusion of science and spirituality that persisted for millennia.

Ancient Egyptian medicine was a complex amalgamation of empirical observation, religious beliefs, and magical practices. While the Egyptians made significant strides in areas like surgery, pharmacology, and anatomy, their healing practices were deeply embedded in the spiritual and magical worldview of the time. The use of incantations, amulets, and rituals to treat illness reflected the belief that health was not just a physical condition but a cosmic and spiritual balance. By combining empirical knowledge with divine intervention, Egyptian medicine offers a fascinating glimpse into how ancient cultures understood the relationship between body, spirit, and the forces of nature, leaving a legacy that influenced later medical and magical traditions.

Greek Speculation

Ancient Greek cosmologies were often speculative, blending early scientific inquiry with philosophical and mystical ideas. One of the most influential schools of thought was the Pythagorean tradition, founded by Pythagoras of Samos around the 6th century BCE. While Pythagoras is best known for his work in mathematics, particularly the Pythagorean theorem, his philosophical views extended deeply into cosmology, mysticism, and the nature of the universe. The Pythagoreans believed that the cosmos was governed by mathematical relationships, and that the physical world could be understood through the study of numbers and their inherent properties. They viewed numbers as more than just abstract symbols; for them, numbers had divine significance and were the very building blocks of reality. This mystical numerology placed them at the intersection of philosophy, science, and religion, reflecting the Greek tendency to seek out underlying principles behind the observable world.

The Pythagoreans believed that the universe itself was an ordered system, a cosmic harmony or cosmos, where everything was connected through mathematical ratios. One of their central ideas was the concept of the “music of the spheres”—the belief that the movements of the planets and celestial bodies created harmonious sounds, though these sounds were beyond human hearing. According to Pythagorean cosmology, the entire universe was structured according to geometric and mathematical principles, and the soul was also subject to these same principles. They believed that the soul could achieve purity by understanding and aligning itself with the divine order of the cosmos, often through ascetic practices, contemplation, and meditation on numbers and their mystical meanings. For the Pythagoreans, achieving harmony with the cosmos was not just a matter of intellectual understanding but of moral and spiritual purification.

The idea that numbers and geometry could represent the fundamental essence of the universe was rooted in the Pythagorean belief in the metaphysical power of numbers. The number “one” was seen as the source of all things, while other numbers had distinct symbolic meanings. The number “two,” for example, represented duality and change, while the number “three” was seen as representing harmony and balance. The number “four” was linked to stability, while the number “ten” (the sum of the first four numbers) was considered a symbol of completeness and perfection. This numerological framework was not merely a mathematical abstraction but was seen as a reflection of divine principles that structured the universe. The Pythagoreans believed that by understanding the nature of numbers and their relationships, one could unlock the secrets of the cosmos and achieve a deeper understanding of reality.

In addition to their focus on numbers and harmony, the Pythagoreans also held mystical and religious beliefs that influenced their cosmology. They believed in the transmigration of souls, or metempsychosis, the idea that souls were reincarnated into new bodies. This doctrine of reincarnation was central to their understanding of the universe and the human soul’s journey. The soul was seen as trapped in a cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, and the only way to escape this cycle was through purification. This purification process involved both intellectual and ethical practices, including the study of mathematics and philosophy, as well as adhering to a strict moral code. The Pythagoreans practiced vegetarianism, abstained from certain foods, and sought to live in harmony with the natural world, believing that these practices would help cleanse the soul and bring it closer to the divine.

Pythagorean cosmology had a profound influence on later Greek philosophers, particularly Plato. Plato’s idea of a rational and harmonious cosmos, governed by ideal forms and mathematical principles, was heavily inspired by Pythagorean thought. Plato’s Timaeus, one of his most important works on cosmology, reflects many of the ideas put forward by the Pythagoreans, including the belief in a divine order to the universe, the connection between mathematics and reality, and the idea that the soul is connected to this cosmic harmony. Moreover, the Pythagorean influence can be seen in the development of Neoplatonism, a philosophical movement that sought to reconcile mystical and rational elements of Greek thought. However, despite their emphasis on mathematics and rational order, Pythagorean cosmology also had elements of mysticism that placed it at the boundary between early philosophy and religious speculation, offering a fascinating blend of rational inquiry and mystical belief.

Roman Birds and Omens

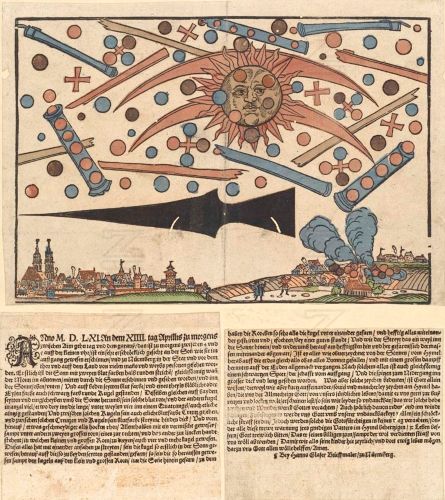

In ancient Rome, superstition and divination were deeply embedded in daily life, influencing everything from political decisions to personal behavior. Romans believed that the world was governed by forces beyond human control, and that these forces could be understood through signs, omens, and divine intervention. The Romans were highly attuned to the natural world and interpreted various phenomena—such as weather patterns, animal behavior, and celestial events—as messages from the gods. Superstitions were widespread, often involving rituals meant to avert bad luck or ensure good fortune. These beliefs were not limited to the lower classes; even the most powerful political figures, including emperors, relied on divination and took omens seriously. The Roman state had its own official diviners, such as the augurs and haruspices, who were employed by the government to interpret signs and ensure the favor of the gods.

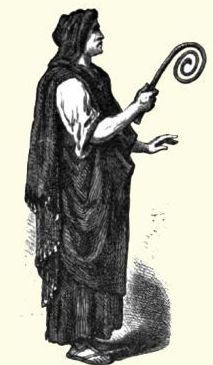

Divination, or the practice of seeking knowledge of the future or the will of the gods, was a key component of Roman superstition. One of the most common forms of divination was auspicy, the practice of interpreting the behavior of birds, particularly their flight patterns. Augurs, or religious officials, would observe the birds’ movements to determine whether they were auspicious signs of divine favor or warnings of impending disaster. Certain types of bird flight, the number of birds seen, and even their species could carry different meanings. This practice was vital in making decisions related to military campaigns, elections, and state rituals. If the auspices were unfavorable, actions might be postponed, or plans altered to appease the gods. Augury was so significant that it became an integral part of Roman political and military life, with officials often awaiting the approval of the gods before making major decisions.

Another important form of Roman divination was haruspicy, the examination of the entrails of sacrificed animals, particularly the liver. The haruspices, who specialized in this practice, believed that the gods revealed their will through the physical characteristics of the animal’s organs. For instance, the size, shape, and color of the liver could indicate the gods’ favor or displeasure. Haruspicy was especially important in times of crisis, such as during wars or before battles, when the outcome was uncertain and the need for divine guidance was paramount. The practice was not restricted to the Roman state; private citizens also engaged in haruspicy to ensure personal success or protection from misfortune. Haruspicy, along with augury, helped to create a society in which divine signs were continually sought to justify decisions and actions, whether in public or private life.

In addition to augury and haruspicy, the Romans also practiced a form of divination known as extispicy, which involved the examination of the internal organs of animals used for sacrifice. The Romans believed that the gods communicated their will not just through omens but also through the very flesh of the animals they offered. This form of divination was often used in conjunction with other rituals, such as the reading of the entrails of chickens, pigs, or sheep. The Romans also placed great importance on the appearance of certain natural phenomena, such as eclipses, comets, and thunderstorms, which were viewed as significant omens from the gods. Public events, including military campaigns and state rituals, were often delayed or altered based on these signs. The significance placed on interpreting natural phenomena shows how superstition and divination were tightly woven into the fabric of Roman religion and governance.

Superstition in ancient Rome extended beyond formal religious practices and permeated the everyday lives of individuals. Romans were highly superstitious, with a wide range of rituals and beliefs aimed at protecting themselves from misfortune and ensuring success. For example, many Romans wore amulets or charms to ward off the evil eye, a concept that was widely believed to cause harm through envy or malevolent intent. These charms were often inscribed with protective spells or symbols, and they were worn by both adults and children. Additionally, Romans frequently engaged in rituals to secure good fortune, such as performing specific actions on certain days of the week or during particular phases of the moon. Certain numbers, such as three, five, and seven, were considered particularly lucky, while others, like the number four, were seen as unlucky. The Romans’ devotion to omens and superstitions demonstrates how they viewed the world as an interconnected web of signs and symbols, where the gods’ will could be understood and shaped through careful attention to the world around them.

Mysticism and Proto-Science in the Medieval Period

Medieval Chemistry and Astrology

Medieval alchemy and astrology were central to both the Islamic and Christian worlds, where they played vital roles in shaping intellectual and spiritual life. In the Islamic world, alchemy was deeply intertwined with the rich legacy of Greco-Roman thought, Persian traditions, and early Islamic philosophy. Alchemists like Jabir ibn Hayyan (Geber), who lived during the 8th century, were crucial in developing early alchemical theories that sought to transmute base metals into gold, discover the philosopher’s stone, and understand the spiritual nature of substances. Alchemists in the Islamic world believed that physical transformation was closely linked with spiritual enlightenment, and many viewed alchemy not just as a science but as a path toward achieving divine wisdom. They were particularly influenced by the Neoplatonism of thinkers like Plotinus and the mystical traditions of Sufism, which emphasized the inner, transformative journey of the soul. Alchemical texts were translated into Latin, significantly influencing medieval European alchemy and astrology, where many of these ideas would later merge with Christian thought.

Astrology, similarly, had a profound impact on the Islamic intellectual tradition. Islamic scholars during the medieval period viewed astrology as both a science and an art, one that could reveal the divine order of the universe through the movements of the stars and planets. Islamic astrologers, such as al-Kindi and al-Battani, made significant contributions to astrological theory and practice, including refinements to the Ptolemaic system of astronomy. Islamic astrologers believed that the positions of celestial bodies could influence events on Earth, including the destinies of individuals and the fortunes of nations. In the Islamic world, astrology was frequently used in the courtly and political realm, helping rulers make decisions about war, governance, and personal matters, such as marriage and childbirth. Much like alchemy, astrology in the Islamic world was an intersection of scientific inquiry and mystical speculation, with the cosmos seen as a reflection of divine order and harmony.

In the Christian medieval world, alchemy and astrology had a somewhat different trajectory, shaped by theological concerns and the Church’s role in the regulation of knowledge. Christian alchemists, such as Thomas Aquinas and Albertus Magnus, were heavily influenced by the works of Islamic alchemists, especially through Latin translations of Arabic texts. Alchemy in the Christian world was initially pursued with the same goal as in the Islamic world: to transmute base metals into gold and to uncover the hidden mysteries of creation. However, Christian alchemists were also concerned with the relationship between material and spiritual transformation. The idea of achieving salvation through the purification of the soul was often paralleled with the purification of substances in alchemical processes. The philosopher’s stone, which could supposedly turn lead into gold, became symbolic of spiritual enlightenment and the quest for eternal life. Alchemy in this context was a blend of proto-science and mysticism, often guided by Christian concepts of redemption, purification, and divine intervention.

Astrology in medieval Christianity was a more contentious practice, especially as the influence of the Church grew during the Middle Ages. While astrology was respected and studied by many scholars, including figures like Roger Bacon and Richard of Wallingford, it was also often viewed with suspicion. The Church maintained that astrology, particularly when it was used to predict events and control human affairs, was contrary to the teachings of the Bible and the sovereignty of God’s will. However, medieval Christians did incorporate astrology into their understanding of the natural world, with many scholars seeing it as a way to interpret divine influence in the cosmos. Christian astrology was often viewed as compatible with Christian teachings when it was used in moderation, particularly when it was employed to understand the natural world rather than to control or predict human behavior. Nonetheless, the Church periodically issued edicts against astrology, and it remained a practice that was both respected and feared in medieval society.

Despite these tensions, the influence of both alchemy and astrology in medieval Christianity and Islam cannot be overstated. The integration of these practices with religious and philosophical systems helped to foster a broader view of the cosmos, one that blended material science with metaphysical and spiritual dimensions. In both the Islamic and Christian worlds, the pursuit of alchemical and astrological knowledge was seen as a means of uncovering divine truths, whether through the transformation of matter or the interpretation of celestial movements. In the Islamic world, this pursuit was more aligned with the intellectual exploration of natural philosophy, while in the Christian world, it was often framed within the context of the soul’s salvation and the divine plan. The cross-cultural exchange of alchemical and astrological knowledge between these two worlds helped shape the intellectual currents of the Middle Ages and laid the groundwork for the scientific and mystical explorations of the Renaissance.

Hermeticism and Neoplatonism

Hermeticism, named after the god Hermes Trismegistus, represents a complex tradition of spiritual, philosophical, and mystical teachings that emerged in the Hellenistic period, particularly around the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE. It is often regarded as a syncretic system, blending Greek philosophical ideas, particularly from Platonism and Stoicism, with Egyptian religious thought. Hermeticism places a strong emphasis on esoteric knowledge, or the pursuit of hidden wisdom that leads to spiritual enlightenment. Central to Hermetic thought is the belief in a divine source or One, from which all things emanate, and the goal of the Hermetic practitioner is to return to this source through intellectual, spiritual, and alchemical practices. Hermetic texts, such as the Corpus Hermeticum, a collection of writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, are filled with dialogues, prayers, and aphorisms that discuss the nature of the universe, the human soul, and the path to divine understanding. These texts became highly influential in both the development of medieval alchemy and the Renaissance revival of mystical and philosophical thought.

One of the core teachings of Hermeticism is the idea of divine unity and the relationship between the macrocosm (the universe) and the microcosm (the individual). According to Hermetic principles, the structure of the universe is mirrored in the structure of the human being, and by understanding oneself, one can understand the divine and the cosmos. This idea reflects the Hermetic axiom “As above, so below,” meaning that the spiritual realities of the universe are reflected in the physical world and vice versa. Hermeticism stresses the importance of personal transformation through the acquisition of secret knowledge (often through initiation or mystical practices), purification of the soul, and understanding the symbolic meanings of natural phenomena. The emphasis on hidden wisdom and its potential to achieve spiritual enlightenment has made Hermeticism one of the most enduring mystical traditions in Western esotericism, influencing later movements like Gnosticism, the Renaissance magical revival, and even the development of modern occultism.

Neoplatonism, which developed through the teachings of philosophers such as Plotinus, Porphyry, Iamblichus, and Proclus during the 3rd to 6th centuries CE, represents a philosophical system that builds upon the ideas of Plato but also incorporates elements of mysticism and metaphysical speculation. Neoplatonism posits the existence of a single, ultimate principle called the One, or the Good, from which all of reality emanates. This One is beyond being and cannot be comprehended by the human mind but is the source of all existence. Neoplatonic cosmology describes a hierarchy of being, with the One at the highest level, followed by the divine intellect (nous), the world soul, and the material world. According to Neoplatonism, everything in the universe is connected through this chain of emanation, and the ultimate goal of human life is to return to the One by transcending the material world and uniting the soul with divine intellect.

While both Hermeticism and Neoplatonism share a belief in a divine, transcendent source and the possibility of human spiritual ascent, they differ in their approach to achieving this ascent. Neoplatonism is more systematic and philosophical, focusing on the intellectual purification of the soul through contemplation and the cultivation of virtues. For Neoplatonists, philosophical reasoning and meditation on the nature of the One are the primary means of achieving union with the divine. Plotinus, for example, emphasized the practice of introspection, where the soul reflects on its own nature and its connection to the divine order. This inner contemplation allows the soul to transcend the material world and reunite with the divine. In contrast, Hermeticism is more eclectic, combining philosophical ideas with practical spiritual exercises such as rituals, prayers, alchemical transformations, and astrological practices. While Hermeticism also stresses intellectual enlightenment, it places greater emphasis on mystical experience and transformation, often involving an engagement with the natural world through symbolism and ritual.

Both traditions played pivotal roles in the development of Western esotericism, influencing early Christian mysticism, medieval alchemy, and Renaissance thinkers like Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola. In the context of early Christianity, Neoplatonism influenced Christian theological thought, particularly in the works of thinkers like Augustine of Hippo, who integrated Neoplatonic ideas with Christian doctrine. Meanwhile, Hermeticism, with its emphasis on hidden knowledge and the pursuit of divine wisdom, became a key source for later occult traditions and influenced Renaissance philosophers who sought to revive ancient mystical teachings. The shared emphasis on spiritual ascent, the interplay between the physical and spiritual worlds, and the belief in a hidden, transcendent reality made both Hermeticism and Neoplatonism foundational to the development of mystical and esoteric traditions in the West. These teachings continue to resonate in modern philosophical and spiritual movements, where their exploration of divine unity, the nature of existence, and the potential for personal transformation remains deeply relevant.

Divination and Scholasticism

In medieval Europe, divination was practiced widely and was considered an important means of understanding divine will and predicting the future. Common forms of divination included astrology, chiromancy (palmistry), geomancy, and the reading of omens. Astrology, in particular, became highly developed during this period, with scholars such as Geoffrey Chaucer in his Treatise on the Astrolabe helping to popularize the practice. Medieval Christians were deeply influenced by the classical works of Ptolemy, who combined astronomy with astrology in a way that provided a framework for predicting events and understanding cosmic influences. Astrological knowledge was applied to a wide range of concerns, from determining the most auspicious dates for important events, such as weddings and battles, to understanding the impact of celestial movements on personal fortunes and health. Despite the strong link between astrology and ancient wisdom, the practice of divination during the medieval period was not universally accepted and often found itself in tension with both Christian theological doctrines and the emerging scholastic tradition.

Alongside astrology, other forms of divination, such as the use of dice, the interpretation of dreams, and even the observation of birds’ flight patterns (a practice known as auspicy), were commonplace in medieval society. These practices were often viewed as means to access hidden knowledge or predict future events. The popularity of divination was not restricted to the lay population; even clergy and royalty often sought the counsel of astrologers and diviners. In particular, royal courts were known to employ astrologers to choose auspicious times for battles or political decisions, while ordinary people sought guidance from fortune-tellers to predict their future. Despite the prominence of divination in daily life, it often faced opposition from religious authorities who saw it as incompatible with Christian doctrine. Divination was frequently associated with the “occult” and viewed as a form of superstition, especially when practiced by non-Christian or pagan practitioners, though even Christian theologians employed astrological or divinatory methods to a certain extent.

The rise of Scholasticism in the medieval period, particularly in the 12th and 13th centuries, brought about a critical reassessment of divination and the occult arts. Scholasticism was a method of intellectual inquiry that sought to reconcile faith with reason, drawing heavily on the works of Aristotle and other classical philosophers. Prominent scholastic thinkers, such as Thomas Aquinas and Albertus Magnus, sought to clarify the relationship between divine will and human agency, and their critiques of divination were based on theological and philosophical grounds. For instance, Aquinas, in his Summa Theologica, argued that divination, when it relied on knowledge of hidden causes (such as astrological influences), undermined the sovereignty of God. According to Aquinas, God alone possessed knowledge of the future, and any attempt by humans to predict or influence the future through divination was a challenge to God’s omniscience and divine plan. Moreover, scholastic philosophers like Aquinas emphasized the importance of free will in human decision-making, and they believed that relying on divination could encourage fatalism, undermining moral responsibility.

One of the key concerns of the scholastics regarding divination was its potential to lead people away from true religious devotion. While the Church officially condemned forms of divination that sought to control or manipulate the future, it also recognized the need for a certain level of understanding of natural events, including astrology, for practical purposes. As a result, there was a nuanced approach to divination within the intellectual framework of the Middle Ages. For example, the study of the heavens was not entirely rejected by the scholastics, as astrology was often integrated into the natural philosophy of the time. However, it was important for scholars to distinguish between astrology as a science of celestial bodies and astrology as a form of divination that attempted to foretell human affairs in a deterministic manner. This was particularly evident in the works of philosophers like Albertus Magnus, who treated astrology as a legitimate scientific pursuit but maintained that its predictive claims should be examined with skepticism, particularly when they conflicted with Christian teachings on divine providence.

The tension between medieval divinatory arts and scholastic critiques continued throughout the Middle Ages, culminating in the later Renaissance, when the study of astrology, alchemy, and magic was often pursued by both intellectuals and mystics. While the Church did not fully condemn the study of the natural world through astrology or other divinatory practices, it did demand that such practices be rooted in an understanding of divine order, rather than being used as a tool for personal gain or as an attempt to control the divine. The scholastic critique of divination ultimately led to a more cautious and intellectual approach to astrology and other mystical practices, with figures such as Giovanni Pico della Mirandola seeking to reconcile ancient knowledge with Christian theology. Despite this intellectual rapprochement, the age-old allure of divination persisted, and the medieval period saw a continued coexistence of religious orthodoxy and esoteric knowledge, paving the way for the more robust exploration of astrology and alchemy during the Renaissance.

Renaissance and Early Modern Esotericism

Paracelsian Medicine

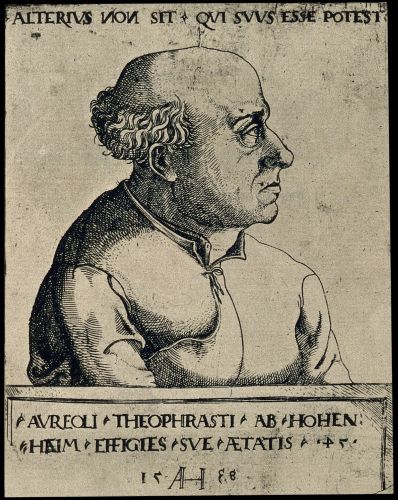

Paracelsian medicine, named after the Swiss physician and alchemist Paracelsus (born Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, 1493–1541), represents a radical departure from the traditional humoral and Galenic medical theories that dominated Europe for centuries. Paracelsus challenged the longstanding authority of Hippocratic and Galenic medicine by advocating for a more empirical, experimental approach to healing, one that was grounded in a deep understanding of chemistry, alchemy, and the natural world. Unlike his predecessors, Paracelsus rejected the idea that disease was primarily caused by imbalances in the four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile) and instead proposed that diseases were the result of external, material causes, such as poisons, infections, and environmental factors. His approach focused on understanding the specific causes of disease at a molecular or elemental level, and he emphasized the importance of individualized treatments rather than the one-size-fits-all remedies prescribed by Galenic medicine.

Central to Paracelsian medicine was the belief in the healing power of chemicals and minerals, which Paracelsus famously referred to as the “spirit of the age.” Unlike traditional medicine, which relied heavily on herbal remedies and natural substances, Paracelsus advocated for the use of minerals and metals as medicinal substances. He believed that these substances had inherent healing properties that could be harnessed for therapeutic purposes. Paracelsus’s use of chemicals and minerals was groundbreaking, as he promoted the idea of using substances like mercury, sulfur, and arsenic in controlled dosages to treat a wide variety of ailments. He was the first to introduce the concept of “dose” in medicine, emphasizing that the right dosage of a substance could heal, while an excessive dose could harm or poison the patient. His ideas about the medicinal use of minerals laid the groundwork for later developments in pharmacology and chemistry, influencing both the study and application of medicinal chemistry in the centuries that followed.

Another key aspect of Paracelsian medicine was its focus on the concept of the “microcosm” and “macrocosm,” drawing on mystical and alchemical ideas that linked human beings to the natural world. Paracelsus believed that the human body was a reflection of the universe, and that a deep understanding of nature and the cosmos was essential for understanding human health. He proposed that each person had an “astral” body, governed by cosmic forces, which was connected to the physical body in a complex, spiritual relationship. This notion of a mystical connection between the body and the cosmos shaped Paracelsus’s approach to healing, as he believed that understanding the spiritual and elemental nature of a disease was just as important as understanding its physical symptoms. He also argued that the physician must not only treat the body but also the spirit, highlighting the importance of mental and emotional health in healing. This holistic view of the body as part of a larger cosmic order was an integral part of Paracelsus’s medical philosophy, setting him apart from more mechanistic views of the body and disease.

Paracelsus’s teachings on medicine were revolutionary, but they were met with strong resistance from the established medical community. The university-trained physicians, who adhered to the humoral theory of Galen, rejected Paracelsus’s unconventional ideas. Paracelsus was a staunch critic of the medical establishment, famously declaring that the work of physicians who followed Galen was nothing more than “bookish medicine” that lacked true understanding of the natural world. He believed that the reliance on ancient texts and theoretical knowledge was insufficient for treating actual patients. Instead, he advocated for an experiential approach to medicine, where the physician should be trained in observation, experimentation, and practical application. Paracelsus’s critiques of established medical practices and his unconventional methods led to his marginalization, and many of his ideas were dismissed as heretical or quackery by the academic medical community. Nevertheless, his influence began to grow, especially among later generations of physicians, alchemists, and chemists, who saw the potential in his approach to medicine.

Despite the initial resistance, the legacy of Paracelsian medicine endured, especially as the field of chemistry and pharmacology began to emerge in the early modern period. His emphasis on the use of minerals and chemicals in medicine laid the foundation for the development of modern pharmaceutical practices. Paracelsus’s belief in the importance of individualized treatment and the role of the physician as both a scientist and a healer became integral to the practice of medicine in the subsequent centuries. In the 17th and 18th centuries, many physicians and chemists began to experiment with Paracelsus’s ideas, leading to advancements in drug development and the eventual creation of more systematic approaches to the use of medicinal substances. Paracelsus’s contributions to medical theory, including his understanding of disease as the result of external causes, were pivotal in moving away from the ancient humoral theory and toward a more scientifically grounded approach to medicine. Though controversial in his time, Paracelsus’s emphasis on empirical observation and his integration of alchemical, spiritual, and naturalistic ideas set the stage for the eventual transformation of Western medicine from medieval to modern practices.

Occult and Magic

During the Renaissance, a profound shift occurred in Western intellectual and cultural life, characterized by a revival of interest in classical antiquity, especially the mystical and esoteric traditions that had been suppressed or marginalized during the medieval period. This period saw the resurgence of occult philosophy, a broad category encompassing the study of hidden or arcane knowledge, which sought to uncover the secret forces governing the cosmos and human existence. Occult philosophy was deeply influenced by the works of ancient Greek and Roman philosophers, particularly Neoplatonism, as well as the rediscovery of ancient Egyptian, Chaldean, and Hermetic texts. These texts, including the Corpus Hermeticum, were thought to contain esoteric wisdom that could unlock the mysteries of the universe and provide spiritual and practical guidance. The rebirth of magic during the Renaissance was intricately connected to this rediscovery of ancient occult traditions, as scholars, alchemists, and mystics began to combine intellectual inquiry with spiritual and supernatural practices.

One of the key figures in this resurgence of occult thought was Marsilio Ficino, an Italian philosopher and translator who is credited with reviving Neoplatonism and integrating it with Christian theology. Ficino’s works, especially his translations of Plato and Plotinus, laid the foundation for much of Renaissance occultism. Ficino viewed magic as a legitimate part of human inquiry, arguing that it was an aspect of divine philosophy, with its origins in the “light” of the One or the Good (the highest principle in Neoplatonism). He famously emphasized the idea that humans could access divine knowledge through intellectual and spiritual practice, linking the human soul to the divine through the contemplation of celestial order. Ficino’s belief in the efficacy of astrology, alchemy, and theurgy—rituals designed to invoke divine beings—was central to Renaissance occultism, as he believed these practices could elevate the soul and bring it closer to the divine.

Ficino was not alone in his enthusiasm for occult practices. Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, another prominent Italian Renaissance thinker, expanded upon Ficino’s work by synthesizing elements of Jewish Kabbalah, Christian mysticism, and Neoplatonism. Pico’s famous work, the Oration on the Dignity of Man, reflects his belief in the potential of human beings to transcend their earthly limitations through the pursuit of hidden knowledge. He argued that humans, as creatures endowed with both material and divine nature, had the unique ability to ascend toward the divine through the study of the occult sciences. Pico’s Kabbalistic and Hermetic teachings were particularly influential in the development of Renaissance magic, as he believed that the use of symbols and rituals could align humans with the higher cosmic order. His fusion of ancient mysticism with Renaissance humanism further reinforced the notion that the pursuit of occult knowledge could be a means of spiritual elevation and self-improvement.

During the Renaissance, the rebirth of magic was also closely tied to the practice of alchemy, which was seen not just as a precursor to modern chemistry, but as a sacred science that could transform both materials and the alchemist’s soul. Paracelsus, the Swiss physician and alchemist, is often considered a key figure in the magical and alchemical traditions of the Renaissance. Paracelsus rejected traditional medical theory and instead advocated for the use of minerals and chemicals as tools for healing, with the underlying belief that these substances had hidden, magical properties. His approach to medicine was part of a larger Renaissance interest in understanding the hidden forces of nature, which included an intense curiosity about the spiritual and material worlds. Alchemists believed that through experimentation and spiritual refinement, they could uncover the secrets of the universe, such as the creation of the philosopher’s stone, which was believed to have the power to turn base metals into gold and grant immortality. This mystical pursuit of alchemy, with its focus on hidden knowledge, made it a crucial part of Renaissance magic.

The rebirth of magic during the Renaissance was also marked by the development of astrology as both a scientific and mystical discipline. Renaissance astrologers, who were heavily influenced by Ptolemaic astronomy, combined the study of celestial movements with the belief that the stars and planets had a direct influence on earthly events. Johannes Kepler, the famous astronomer, is often seen as an example of this blend of astrology and emerging science. Although Kepler later distanced himself from astrology, he was initially drawn to it, and his early work reflects the Renaissance ideal that cosmic harmony could reveal spiritual truths. For many Renaissance scholars, astrology was a tool for understanding the divine order, and it was frequently used in conjunction with other forms of occultism, such as alchemy and magic, to help interpret the will of the heavens and guide human affairs. This worldview held that by understanding and manipulating cosmic forces, individuals could gain insight into the divine plan and achieve spiritual or material goals.

The rebirth of magic during the Renaissance represented a synthesis of mysticism, science, and philosophy, blending ancient occult traditions with the intellectual currents of the period. It was a time when human beings sought to bridge the gap between the material and spiritual worlds, using occult knowledge to unlock hidden truths about the universe and their place within it. While the church often viewed such practices with suspicion, regarding them as potentially heretical or dangerous, many Renaissance thinkers saw magic as a means of achieving enlightenment and spiritual transformation. The flourishing of occultism during this period laid the groundwork for later mystical movements and influenced the development of Western esotericism, setting the stage for a continuing exploration of magic, alchemy, and astrology in the centuries to come.

Skepticism and Rational Pushback

During the Renaissance, the revival of classical antiquity brought with it not only a flourishing of new ideas in art, science, and philosophy, but also a renewed examination of the intellectual foundations of Western thought. The period, which was marked by an increased focus on human reason and empirical inquiry, saw the rise of early forms of skepticism—a philosophical stance that questioned the reliability of human knowledge and emphasized the limitations of reason. Skeptical thinkers challenged the prevailing religious and medieval scholastic doctrines, which had been heavily based on authority and theological interpretation. Figures like Michel de Montaigne, whose work Essays laid the foundation for modern skepticism, argued that human knowledge was inherently limited and that reason was often unreliable. Montaigne’s skepticism was not so much a rejection of reason but rather a caution against its overreach, urging intellectual humility and the acceptance of the uncertainty of human existence. Montaigne’s insistence on the complexity of human perception and the variability of experience reflected a growing concern about the limits of what could be known with certainty.

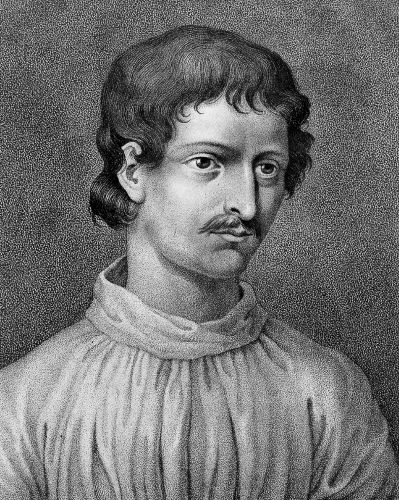

Skepticism during the Renaissance also had significant implications for theology and the ongoing tensions between reason and faith. While the Catholic Church continued to dominate religious thought, there was an increasing questioning of traditional religious authorities and doctrines, spurred by the intellectual movements of the time. Renaissance thinkers, influenced by the revival of Greek and Roman thought, began to emphasize the importance of individual inquiry and personal judgment over institutional dogma. Giordano Bruno, for example, was a philosopher and cosmologist who argued for a more expansive, empirical approach to understanding the universe, rejecting the geocentric model of the universe espoused by the Church. Bruno’s views on the infinity of the universe and the multiplicity of worlds were radical for his time and led to his eventual execution for heresy. His ideas represented a challenge not only to the religious orthodoxy of the Church but also to the broader Aristotelian and scholastic philosophy that had dominated the intellectual world of the medieval period.

The Renaissance also saw a rationalist pushback against mystical and occult traditions, which had flourished alongside the resurgence of occult philosophy and magic. The rise of empiricism and a more scientific approach to knowledge led many thinkers to question the validity of mystical practices like alchemy, astrology, and divination. One of the key figures in this movement was Francis Bacon, an English philosopher who is often credited with laying the groundwork for modern scientific methodology. Bacon’s emphasis on inductive reasoning, observation, and experimentation marked a decisive break from medieval modes of thought, which often relied on deductive reasoning from established principles. Bacon’s writings, especially his work Novum Organum, called for a rigorous, empirical approach to understanding the natural world, which he believed could only be achieved through systematic observation and the collection of data, rather than relying on ancient authorities or esoteric traditions. His rationalist perspective offered a stark contrast to the mystical and speculative ideas that had gained traction in the Renaissance, arguing that knowledge should be built from the ground up rather than based on abstract or mystical theories.

Another influential figure in the rationalist pushback was René Descartes, whose philosophical and scientific writings laid the foundation for modern philosophy and the scientific revolution. Descartes is best known for his famous dictum, Cogito, ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”), which encapsulates his belief in the primacy of reason and the ability of human thought to achieve certainty. Descartes’s skepticism was profound and systematic; in his Meditations on First Philosophy, he doubted everything that could possibly be doubted, including the existence of the external world and his own body. His goal was to arrive at an indubitable foundation for knowledge, which he ultimately found in the certainty of his own existence as a thinking being. Descartes’s approach to skepticism was grounded in rationalism, as he believed that human reason could achieve absolute certainty, in contrast to the Renaissance emphasis on subjective perception and the mystical aspects of knowledge. Descartes’s philosophy was a direct challenge to both the mystical elements of Renaissance thought and the medieval reliance on authority and tradition, offering a vision of knowledge that was based on clear, logical reasoning and doubt-free certainty.

The skepticism and rationalism of the Renaissance had lasting implications for the intellectual climate of the early modern period. As the period progressed, the ideas of early skeptics and rationalists laid the foundation for the scientific revolution, which would forever change the trajectory of Western thought. Thinkers like Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, and Isaac Newton would build upon the foundations of empirical inquiry and rational analysis laid by figures like Bacon and Descartes. The growing emphasis on empiricism, mathematics, and natural philosophy gradually displaced the speculative and mystical approaches to knowledge that had dominated the medieval period. The rationalist pushback of the Renaissance, with its focus on reason, evidence, and critical inquiry, helped to shift the focus of intellectual life away from religious and esoteric explanations of the world and toward scientific methods that sought to explain natural phenomena through observation, experimentation, and mathematical reasoning. This intellectual transformation would become the hallmark of the Enlightenment and ultimately the modern world, shaping the way we understand knowledge, science, and human progress.

The Enlightenment and the Boundaries of Science

Mesmer’s Vitalism

Mesmerism, named after the German physician Franz Anton Mesmer, was a highly influential and controversial system of thought that emerged in the late 18th century and would go on to inspire both medical and mystical ideas. Mesmer’s central theory was that the human body was influenced by an invisible natural force, which he called “animal magnetism” or simply “mesmerism”. According to Mesmer, the body contained an energy force that could be manipulated through various techniques, most notably the application of magnets and the act of “mesmerizing” a patient. Mesmer believed that imbalances or blockages in the flow of this energy caused illness, and that by restoring its balance through controlled influence, he could cure a range of physical and psychological ailments. While his theories were often seen as pseudoscientific, Mesmerism gained widespread popularity in Europe, particularly in France, where it became a sensation among both the medical community and the general public. The famous case of the “Baquet” (a device that supposedly harnessed animal magnetism to cure illness) and Mesmer’s highly publicized demonstrations contributed to the rise of mesmerism as a form of medical therapy, despite the skepticism and criticism it faced from established medical authorities.

The practice of Mesmerism was deeply connected to the broader intellectual climate of the Enlightenment, an era in which reason and scientific inquiry were increasingly prized over superstition and mysticism. However, Mesmerism did not entirely conform to the rationalist ideals of the Enlightenment. While Enlightenment thinkers such as René Descartes and Isaac Newton sought to explain the natural world through reason, empirical observation, and scientific laws, Mesmer’s theory of invisible energies seemed to revert to a more mysterious, vitalistic understanding of nature. The French Enlightenment physician Denis Diderot, for example, was initially intrigued by Mesmer’s ideas but also critiqued the lack of empirical evidence behind his claims. The French Royal Commission, which was assembled in 1784 to investigate the validity of Mesmerism, included prominent thinkers such as Antoine Lavoisier and Benjamin Franklin, who concluded that Mesmer’s animal magnetism was not scientifically plausible. Despite this, Mesmerism’s popularity persisted, influencing both medical practice and the emerging field of hypnosis, which would become a significant area of study in the 19th century.

Mesmer’s ideas were part of a larger movement of vitalism, a theory in philosophy and biology that proposed that life was governed by a force distinct from the mechanical laws of physics. Vitalism posited that living organisms possessed an immaterial, “vital force” or “life force” that animated the body and governed its functions. This idea was particularly influential in the medical and biological sciences of the period. Vitalism can be seen as a response to the rise of mechanical philosophy (which viewed the body as a machine) and Newtonian physics, which applied mechanical laws to the workings of the universe. Vitalists, however, rejected the idea that life could be fully explained through mechanical processes alone. Instead, they suggested that living organisms were governed by an intangible force or energy that could not be explained by material science. Mesmerism, with its emphasis on a vital force influencing health and illness, was a practical application of this broader philosophical movement.

The notion of vitalism had roots in earlier philosophical traditions, particularly in the works of Rene Descartes, who believed that the body could be understood through mechanical principles, but that the soul, or “mind,” was a separate, non-material entity. However, vitalism took a more holistic turn during the Enlightenment, drawing on ideas from French medicine and German philosophy. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and other German idealists argued that the “life force” was a dynamic, organizing principle that was responsible for the unity of the organism. The idea of an invisible vital force was also reflected in the writings of Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta, whose experiments with electrical currents in living tissue hinted at the possibility of an unknown energy influencing biological processes. The notion of animal magnetism, introduced by Mesmer, was just one manifestation of this vitalistic thinking, linking invisible forces to physical health. While the exact nature of the “life force” remained unclear, vitalism opened up new avenues for thinking about the relationship between the body, mind, and nature, and it continued to influence medical theories until the development of cell theory and modern biochemistry in the 19th century.

Although Mesmerism and vitalism ultimately did not survive as dominant theories in medical practice, their legacy continued to shape the development of psychological and medical sciences. The work of Mesmer directly influenced the later development of hypnosis and psychosomatic medicine, areas that recognize the interplay between the mind and body in the treatment of illness. Furthermore, vitalist ideas contributed to the eventual birth of holistic health practices, which view the body as a complex system influenced by not just physical factors, but also mental, emotional, and spiritual forces. The Enlightenment’s emphasis on rationalism, scientific observation, and empirical evidence challenged and eventually replaced vitalist and mesmerist theories. Still, the early interest in unseen forces and the potential of the human mind to influence physical health foreshadowed future developments in psychology, neuroscience, and energy medicine, making Mesmerism and vitalism key precursors to modern explorations of the mind-body connection.

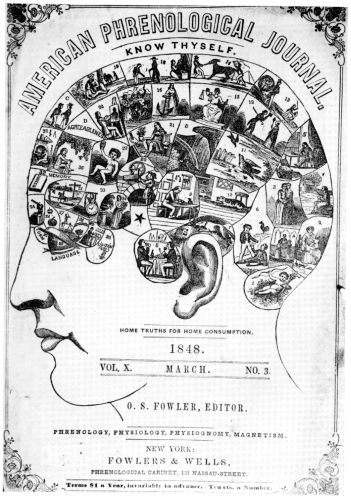

Head Shapes

Phrenology, a pseudoscience that claimed to determine an individual’s character, personality traits, and mental faculties based on the shape and size of the skull, emerged during the Enlightenment as a system that purported to blend scientific inquiry with social theory. Founded by Franz Joseph Gall in the late 18th century, phrenology argued that different areas of the brain were responsible for specific intellectual, emotional, and moral functions. Gall proposed that the shape of a person’s skull would reflect the development of these areas of the brain, and by measuring the contours and bumps on the skull, one could infer a person’s traits. While initially focused on the study of the human brain and its faculties, phrenology quickly took a turn toward racial and social classifications, which would come to have dangerous implications for the development of scientific racism. This theory, which claimed to explain differences in intelligence, behavior, and moral character, was widely accepted in Europe and the United States for much of the 19th century and became a cornerstone of pseudo-scientific attempts to justify racial hierarchies.