The desire for equitable health services and the realities of geographic and economic challenges.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Rural health care in the United States has been shaped by unique challenges and historical developments that differ markedly from urban health systems. Geographic isolation, limited infrastructure, and a lower density of medical professionals have long defined the health care experience for rural Americans. This essay traces the evolution of rural health care from the early colonial period through the twentieth century, highlighting key policies, technological advancements, and social movements that influenced its development. Understanding this history is essential to addressing ongoing disparities in rural health care access and outcomes today.

Early Colonial and 19th Century Health Care in Rural America

The earliest forms of health care in rural colonial America were characterized by a combination of Indigenous knowledge, folk practices, and rudimentary European medical theory. Colonists settling in the New World encountered an unfamiliar environment and diseases to which they had limited immunity. Without formal infrastructure or trained physicians in many rural areas, early settlers often turned to Indigenous peoples for remedies, many of which proved effective in treating local illnesses. Herbalism, poultices, and spiritual rituals influenced settler practices, creating a hybrid form of medicine that relied heavily on plants such as willow bark, sassafras, and echinacea.1 In these isolated communities, midwives, family members, and local healers were the primary care providers, with women playing a central role in community health. The absence of hospitals or formal clinics meant that health care was a home-centered endeavor, often inseparable from daily domestic life.2

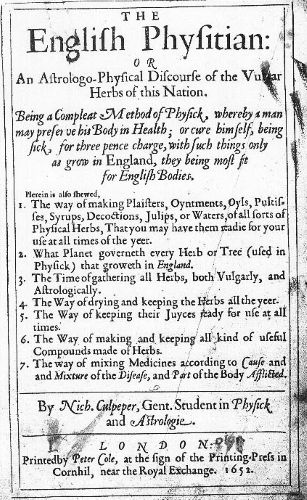

As the 18th century progressed, formal medicine began to take root in the urban centers, but rural regions remained largely dependent on informal care. The American Revolution further disrupted medical progress, as shortages of supplies and trained personnel exacerbated conditions in the countryside. Rural doctors, if present, were usually generalists with minimal training—often apprentices rather than formally educated professionals. Their therapeutic arsenal was limited and frequently harmful, including bloodletting, purging, and the use of toxic substances like mercury.3 Moreover, the geographic isolation of rural areas meant that even the dissemination of updated medical knowledge lagged behind urban counterparts. Medical journals and lectures were often inaccessible, and many rural practitioners relied on outdated texts such as Nicholas Culpeper’s The English Physician or domestic medical guides that emphasized self-treatment.4 The lack of licensing standards allowed charlatans and “quack” doctors to operate freely, contributing to a widespread mistrust of formal medicine among rural populations.

The 19th century saw significant, albeit uneven, improvements in rural health care, shaped largely by social reform movements, advances in transportation, and the spread of medical education. The rise of the Second Great Awakening and its associated reform impulses fostered a spirit of civic responsibility that led to the creation of voluntary health organizations, including those aimed at sanitation and temperance. The expansion of railroads helped to bridge the urban-rural divide, enabling doctors and medications to travel farther and faster than before. Simultaneously, the proliferation of medical schools—although varying greatly in quality—meant that more physicians were practicing in rural areas, though their standards of training remained inconsistent well into the mid-century.5 The Civil War served as a catalyst for both innovation and dissemination of medical practices, and postbellum rural America began to see the emergence of more structured care systems, including the occasional rural hospital or dispensary, often affiliated with religious or philanthropic groups.6

Despite these advances, many rural Americans continued to depend on home remedies, self-treatment, and the assistance of midwives and herbalists. The 19th century was also the golden age of patent medicine, and rural consumers were prime targets for its promises of cure-alls, distributed via traveling salesmen and increasingly persuasive advertising in almanacs and newspapers. These products were rarely regulated and often contained alcohol, opium, or other addictive substances.7 Trust in institutional medicine was slow to grow, and the gap between urban and rural health care remained substantial. Access to reliable medical care was often determined not only by geography but also by socioeconomic status, with poorer rural families disproportionately affected by epidemics and chronic illnesses. The persistence of diseases such as cholera, tuberculosis, and diphtheria in rural communities underscored the limited reach of public health initiatives during this period.8

Early colonial and 19th-century rural American health care was defined by its adaptability, resilience, and tension between tradition and emerging professional standards. The legacy of informal caregiving, the influence of Indigenous and African American healing traditions, and the evolving role of women in medical care all contributed to a uniquely American approach to rural health. Though the formalization of medicine would eventually dominate the 20th century, the foundations laid in earlier centuries remained evident in the communal and often improvisational character of rural care. Understanding this evolution reveals how deeply medical practice is embedded in cultural, social, and environmental contexts. The rural experience stands as a testament to the ingenuity of communities faced with profound challenges and limited resources, and it invites continued scholarly attention to the intersections of medicine, geography, and identity in American history.9

The Rise of Public Health and Rural Medicine in the Early 20th Century

The early 20th century marked a transformative period in American health care, particularly in the development of public health and rural medicine. Spurred by the urban Progressive reform movement of the late 19th century, the new century saw these reforms extend into the rural hinterlands. Central to this development was the belief that the state had a responsibility to ensure the health of its citizens, regardless of location. This was a radical departure from earlier laissez-faire attitudes. The Progressive Era’s emphasis on scientific management, education, and social responsibility was evident in emerging public health campaigns aimed at eradicating infectious diseases and improving sanitation in rural regions. Organizations such as the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS), state health departments, and philanthropic foundations like the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission played crucial roles in institutionalizing rural public health infrastructure.10 These agencies emphasized the prevention of disease through community-level initiatives rather than individual medical care, a shift that would redefine public health in the countryside.

The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission’s hookworm eradication campaign from 1909 to 1914 was a landmark initiative that brought national attention to the poor health conditions in the rural South. This campaign combined education, sanitation improvement, and medical intervention to combat what was then a widely underestimated parasite causing anemia and lethargy among millions.11 The success of the campaign not only validated the utility of public health outreach in rural regions but also set a precedent for future collaborations between private philanthropy and public health institutions. Furthermore, it demonstrated the efficacy of combining scientific research with grassroots mobilization. Nurses, educators, and field agents were deployed to even the most remote communities to build latrines, promote personal hygiene, and collect epidemiological data.12 The campaign’s legacy extended beyond hookworm, catalyzing broader health reforms including the establishment of county health departments and the training of local health officers throughout the South and beyond.

Alongside these developments, the emergence of the rural visiting nurse and county health nurse programs became essential components of early 20th-century rural health care. These nurses were often the sole health professionals regularly seen by rural families. Funded by state governments, private donations, and local community efforts, they traveled long distances to provide vaccinations, prenatal and infant care, and basic medical treatments. Their work was deeply personal, rooted in trust and community engagement, and often included health education initiatives designed to instill habits aligned with modern medical standards.13 These nurses functioned as intermediaries between isolated communities and the growing field of professional medicine, and their success helped justify broader public investment in rural health. Moreover, they offered a model for how public health principles could be applied on a household level in communities that had long been disconnected from urban medical institutions.14

Another significant development was the passage of the Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Act of 1921, the first major federal welfare program focused on maternal and child health. Though ultimately short-lived, repealed in 1929, the act had a substantial impact on rural medicine. It funded health clinics, provided salaries for rural health workers, and supported public health education materials targeting new mothers.15 These interventions lowered infant and maternal mortality rates in rural areas and increased the visibility of women’s health as a public concern. It also helped normalize government involvement in personal health, paving the way for later federal programs such as the New Deal’s health initiatives and, eventually, Medicaid and Medicare. Though controversial at the time, opposed by the American Medical Association and conservative lawmakers, the program nonetheless revealed how federal-state partnerships could address regional disparities in health care access and outcomes.16

Despite these advancements, structural barriers to health equity remained entrenched throughout much of rural America. Geographic isolation, poverty, racial segregation, and underfunded infrastructure continued to limit the effectiveness of public health programs. However, the early 20th century laid the groundwork for a more integrated and professionalized approach to rural health care. The period witnessed the gradual transition from individualized, folk-based medicine to a coordinated system emphasizing disease prevention, standardized care, and governmental responsibility. By 1930, most states had established county health departments, and public health nursing was recognized as a vital component of rural health delivery.17 These achievements were not merely the product of government policy but the result of sustained advocacy by reformers, educators, and health professionals dedicated to improving the lives of rural Americans. Their legacy is evident in the foundational public health structures still in place today.

The New Deal and Rural Health Care Expansion

The Great Depression devastated rural America, exacerbating already precarious health conditions in farming communities, mining towns, and remote settlements. Malnutrition, inadequate sanitation, and a collapse in income left rural populations vulnerable to disease and premature death. The New Deal, introduced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in response to this national crisis, marked a turning point in the federal government’s role in rural health care. While the New Deal’s primary focus was economic recovery, several of its programs laid essential groundwork for the expansion of health services in underserved areas. Agencies such as the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) included health care components that delivered direct services to impoverished communities and promoted preventative medicine.18 For many rural Americans, these initiatives represented their first contact with organized, government-sponsored medical care.

The Public Works Administration (PWA) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) played a vital role in building the physical infrastructure necessary for rural health improvement. These agencies funded the construction and renovation of hospitals, clinics, sanitation systems, and water treatment facilities in small towns and agricultural regions.19 This development was critical in an era when many rural communities lacked even basic plumbing or waste management systems. In tandem, the CCC provided physical examinations, vaccinations, and medical care to young men working in remote camps, introducing public health as a facet of civic service.20 The Health Division of the WPA hired thousands of unemployed medical professionals—including nurses, dentists, and physicians—who brought clinical services to schools and homes in isolated rural areas. These efforts contributed not only to improved health outcomes but also to the normalization of public health intervention as a legitimate and beneficial presence in rural life.

The Social Security Act of 1935 institutionalized this shift by embedding public health in the fabric of federal policy. Title VI of the Act allocated federal funds to state health departments for the development of rural health programs, especially maternal and child health services.21 This represented a significant advancement over earlier piecemeal efforts, enabling states to hire staff, expand health education, and provide clinical services on a more sustained basis. Although the Act did not establish a national health insurance program—something Roosevelt’s administration briefly entertained—it fundamentally changed the relationship between rural citizens and the federal government regarding health. By making health services a function of state responsibility supported with federal dollars, the New Deal laid the administrative and ideological foundation for postwar health initiatives such as the Hill-Burton Act and Medicare.22

Despite these achievements, the New Deal’s health reforms were unevenly implemented and often constrained by local political dynamics, including racial segregation in the South and resistance to federal authority in many western and Appalachian communities. Nevertheless, the period saw the growth of an ethos that public health was a national concern. Rural communities increasingly participated in public health programs, with an expanding workforce of public health nurses and county health officers bringing preventive care to areas that had once been left to self-treatment and folklore. Partnerships between local governments, land-grant universities, and federal agencies proliferated, promoting public health campaigns against tuberculosis, syphilis, and nutritional deficiency diseases like pellagra.23 Health fairs, mobile clinics, and school-based programs became commonplace, reinforcing the idea that medicine and citizenship were interlinked.

By the end of the 1930s, the New Deal had made an indelible mark on rural health care by connecting federal resources with local needs. Though still far from equitable or comprehensive, rural health infrastructure had improved dramatically compared to the 1920s. Importantly, these gains were achieved not merely through bricks-and-mortar investments, but through the transformation of rural Americans’ expectations. The concept of health as a public good and a shared responsibility began to displace older, more individualistic views of medical care. While World War II would soon divert attention and resources, many of the professionals, institutions, and policy mechanisms created during the New Deal era would persist and evolve, ultimately feeding into the postwar expansion of American health care.24 This period stands as a crucial chapter in the historical trajectory that led from isolated, informal rural health traditions to a more integrated and federally-supported system of care.

Conclusion

The history of rural health care in America reveals a persistent tension between the promise of equitable health services and the realities of geographic and economic challenges. From informal colonial-era remedies to modern telemedicine innovations, rural health care has evolved through a complex interplay of social, economic, and political factors. Continued investment in infrastructure, workforce development, and technology will be essential to addressing the enduring disparities faced by rural Americans.

Appendix

Endnotes

- William G. Rothstein, American Physicians in the Nineteenth Century: From Sects to Science (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985), 12.

- Elaine G. Breslaw, Lotions, Potions, Pills, and Magic: Health Care in Early America (New York: NYU Press, 2012), 45–47.

- James H. Cassedy, Medicine in America: A Short History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), 28–30.

- Steven Stowe, Doctoring the South: Southern Physicians and Everyday Medicine in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 58–60.

- Charles E. Rosenberg, The Care of Strangers: The Rise of America’s Hospital System (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987), 78–79.

- John Duffy, The Healers: A History of American Medicine (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1979), 210–12.

- Sarah W. Tracy, Alcoholism in America: From Reconstruction to Prohibition (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005), 95.

- Nancy Tomes, The Gospel of Germs: Men, Women, and the Microbe in American Life (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998), 102–105.

- Breslaw, Lotions, Potions, Pills, and Magic, 173–76.

- Elizabeth Fee and Theodore M. Brown, Making Medical History: The Life and Times of Henry E. Sigerist (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 122–24.

- John Ettling, The Germ of Laziness: Rockefeller Philanthropy and Public Health in the New South (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981), 5–8.

- Nancy Tomes, Remaking the American Patient: How Madison Avenue and Modern Medicine Turned Patients into Consumers (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 112–14.

- Tomes, Remaking the American Patient.

- Susan M. Reverby, Ordered to Care: The Dilemma of American Nursing, 1850–1945 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 178–82.

- Molly Ladd-Taylor, Raising a Baby the Government Way: Mothers’ Letters to the Children’s Bureau, 1915–1932 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1986), 67–70.

- Robyn L. Rosen, Reproductive Health, Reproductive Rights: Reformers and the Politics of Maternal Welfare, 1917–1940 (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2003), 53–56.

- John Duffy, From Humors to Medical Science: A History of American Medicine (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 212–15.

- Nancy E. Rose, Put to Work: The WPA and Public Employment in the Great Depression (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2009), 115–17.

- John Duffy, From Humors to Medical Science, 220–22.

- Otis L. Graham, The New Deal: The Depression Years, 1933–1940 (New York: Krieger, 1983), 154–56.

- Karen Tice, Tales of Wayward Girls and Immoral Women: Case Records and the Professionalization of Social Work (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 92–94.

- Beatrix Hoffman, The Wages of Sickness: The Politics of Health Insurance in Progressive America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 139–42.

- David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz, Deadly Dust: Silicosis and the On-Going Struggle to Protect Workers’ Health (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006), 90–93.

- Alan Derickson, Health Security for All: Dreams of Universal Health Care in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005), 73–76.

Bibliography

- Breslaw, Elaine G. Lotions, Potions, Pills, and Magic: Health Care in Early America. New York: NYU Press, 2012.

- Cassedy, James H. Medicine in America: A Short History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

- Derickson, Alan. Health Security for All: Dreams of Universal Health Care in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005.

- Duffy, John. From Humors to Medical Science: A History of American Medicine. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

- Duffy, John. The Healers: A History of American Medicine. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1979.

- Ettling, John. The Germ of Laziness: Rockefeller Philanthropy and Public Health in the New South. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981.

- Fee, Elizabeth, and Theodore M. Brown. Making Medical History: The Life and Times of Henry E. Sigerist. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

- Graham, Otis L. The New Deal: The Depression Years, 1933–1940. New York: Krieger, 1983.

- Hoffman, Beatrix. The Wages of Sickness: The Politics of Health Insurance in Progressive America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

- Ladd-Taylor, Molly. Raising a Baby the Government Way: Mothers’ Letters to the Children’s Bureau, 1915–1932. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1986.

- Reverby, Susan M. Ordered to Care: The Dilemma of American Nursing, 1850–1945. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- Rose, Nancy E. Put to Work: The WPA and Public Employment in the Great Depression. New York: Monthly Review Press, 2009.

- Rosen, Robyn L. Reproductive Health, Reproductive Rights: Reformers and the Politics of Maternal Welfare, 1917–1940. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2003.

- Rosenberg, Charles E. The Care of Strangers: The Rise of America’s Hospital System. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987.

- Rosner, David, and Gerald Markowitz. Deadly Dust: Silicosis and the On-Going Struggle to Protect Workers’ Health. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006.

- Rothstein, William G. American Physicians in the Nineteenth Century: From Sects to Science. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985.

- Stowe, Steven. Doctoring the South: Southern Physicians and Everyday Medicine in the Mid-Nineteenth Century. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

- Tice, Karen. Tales of Wayward Girls and Immoral Women: Case Records and the Professionalization of Social Work. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998.

- Tomes, Nancy. Remaking the American Patient: How Madison Avenue and Modern Medicine Turned Patients into Consumers. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

- Tomes, Nancy. The Gospel of Germs: Men, Women, and the Microbe in American Life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Tracy, Sarah W. Alcoholism in America: From Reconstruction to Prohibition. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.20.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.