The legacy of the early American partisan press is complex.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The press in the early American republic played a crucial and controversial role in shaping political culture, influencing public opinion, and framing the boundaries of acceptable political discourse. Far from being a neutral or disinterested observer of public affairs, the early American press was a deeply partisan institution. Newspapers served as instruments of political parties and were pivotal in the formation of the nation’s first party system. The rise of partisan media in the late 18th and early 19th centuries exemplified both the promise and peril of a free press in a republican society. This essay explores the development of partisan media in early America, its entanglement with the emerging party system, and its broader implications for democratic discourse and political legitimacy in the fledgling republic.

The Origins of the Partisan Press

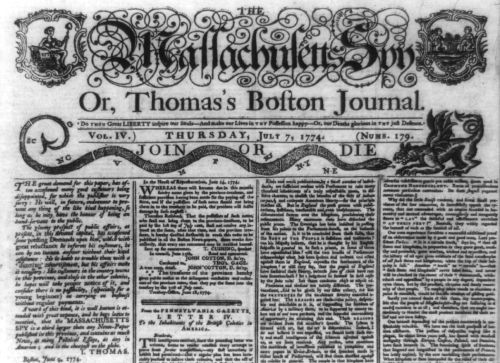

In the immediate aftermath of the American Revolution, newspapers were few in number and largely focused on commercial news, reprinted essays, and foreign affairs. However, as the new republic began to take shape, the press quickly assumed a more overtly political function. The 1790s witnessed the formation of the first American political parties: the Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton and John Adams, and the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. These emerging factions utilized newspapers as ideological weapons in an increasingly contentious political landscape.

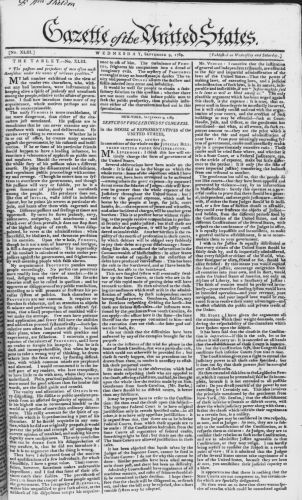

The Gazette of the United States, founded by John Fenno in 1789, was arguably the first national partisan newspaper. It functioned as the semi-official mouthpiece of the Washington administration and closely aligned with Federalist ideology. Fenno’s paper emphasized national unity, support for the Constitution, and deference to central authority—core Federalist values.1 Jefferson, alarmed by the influence of this Federalist press, responded by supporting Philip Freneau’s National Gazette, established in 1791, which became the leading Democratic-Republican organ.2 These papers did not pretend to impartiality. Instead, they unabashedly served the interests of their respective factions, often attacking their opponents in scathing and personal terms.

Media as Party Machinery

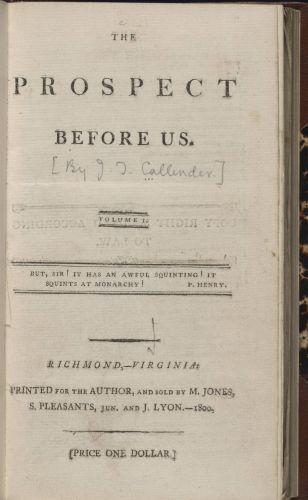

The relationship between the press and party politics in early America was symbiotic. Political leaders provided financial support, insider access, and ideological direction to sympathetic editors, who in turn used their newspapers to rally supporters, attack opponents, and define the public agenda. Editors such as Benjamin Franklin Bache, William Duane, and James Callender became prominent figures in their own right, often blurring the lines between journalism and political activism.

This partisan ecosystem was sustained by a system of government printing contracts, partisan patronage, and even direct subsidies. For instance, Jefferson, while Secretary of State, arranged for Freneau to be appointed as a translator at the State Department, a sinecure intended to support his journalistic endeavors.3 Meanwhile, Federalist newspapers received lucrative contracts for printing laws and government documents, reinforcing their loyalty to the administration.4

The content of these newspapers reflected their partisan orientation. Editorials, essays, and letters were often polemical and inflammatory. Accusations of tyranny, sedition, and corruption were commonplace. The press portrayed political opponents not merely as mistaken, but as existential threats to the republic. This climate of intense political polarization contributed to a volatile and often violent public sphere.

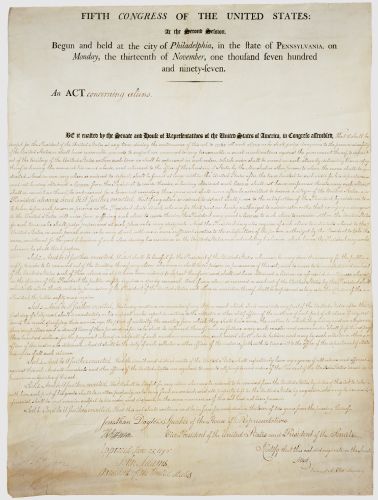

The Press and the Alien and Sedition Acts

The increasingly acrimonious tone of partisan journalism reached a crisis point with the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798. Enacted by the Federalist-controlled Congress, these laws criminalized criticism of the federal government and were clearly aimed at silencing Republican newspapers. The Sedition Act in particular made it a crime to “write, print, utter, or publish… any false, scandalous and malicious writing” against the government.5

Several Republican editors, including Bache and Callender, were prosecuted under the Sedition Act. These prosecutions galvanized public opinion and became a rallying point for the Democratic-Republicans, who portrayed the laws as a betrayal of the First Amendment and an authoritarian overreach. The controversy surrounding the Alien and Sedition Acts highlighted the central role of the press in defining the boundaries of legitimate dissent and underscored the high stakes of partisan journalism.6

Democratic Expansion and the Penny Press

By the 1820s and 1830s, the nature of American journalism began to shift with the emergence of the penny press. These newspapers, such as Benjamin Day’s New York Sun (founded in 1833), sought to appeal to a mass audience and often focused on sensational stories, crime reports, and human-interest features rather than overt political partisanship.7 However, partisan newspapers continued to flourish alongside these new outlets, particularly as the Second Party System coalesced around the Democrats and the Whigs.

Editors like Amos Kendall (for Andrew Jackson) and Horace Greeley (founder of the New-York Tribune and a Whig supporter) played prominent roles in party politics. Kendall even served as Postmaster General, using his position to favor Jacksonian newspapers through selective postal subsidies and distribution networks.8 While the tone and style of journalism evolved, the partisan function of much of the press remained entrenched well into the mid-19th century.

Conclusion

Partisan media in early America was not an aberration, but rather a defining feature of the nation’s political development. Far from undermining democratic norms, the partisan press helped to establish them by fostering political participation, articulating competing visions of governance, and holding power to account—albeit through highly combative means. At the same time, the often vitriolic nature of partisan journalism exposed the vulnerabilities of the republic’s democratic institutions and tested the limits of freedom of expression.

The legacy of the early American partisan press is complex. It laid the groundwork for modern political communication while also serving as a cautionary tale about the dangers of factionalism and the politicization of truth. In a modern media landscape increasingly characterized by ideological polarization, the experience of the early republic offers both historical precedent and enduring lessons.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Jeffrey L. Pasley, “The Tyranny of Printers”: Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001), 47–48.

- Marcus Daniel, Scandal and Civility: Journalism and the Birth of American Democracy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 87.

- James Morton Smith, Freedom’s Fetters: The Alien and Sedition Laws and American Civil Liberties (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1956), 98–99.

- Pasley, “The Tyranny of Printers”, 51.

- U.S. Congress, Alien and Sedition Acts, 1798, in The Founders’ Constitution, ed. Philip B. Kurland and Ralph Lerner (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), Vol. 5, Doc. 23.

- Smith, Freedom’s Fetters, 250–256.

- Michael Schudson, Discovering the News: A Social History of American Newspapers (New York: Basic Books, 1978), 24–27.

- David Greenberg, Republic of Spin: An Inside History of the American Presidency (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016), 33–34.

Bibliography

- Daniel, Marcus. Scandal and Civility: Journalism and the Birth of American Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Greenberg, David. Republic of Spin: An Inside History of the American Presidency. New York: W.W. Norton, 2016.

- Pasley, Jeffrey L. “The Tyranny of Printers”: Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001.

- Schudson, Michael. Discovering the News: A Social History of American Newspapers. New York: Basic Books, 1978.

- Smith, James Morton. Freedom’s Fetters: The Alien and Sedition Laws and American Civil Liberties. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1956.

- U.S. Congress. Alien and Sedition Acts. 1798. In The Founders’ Constitution, edited by Philip B. Kurland and Ralph Lerner. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.21.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.