The real action in 2025 will come from the leaders of states and provinces.

By Mary D. Nichols, J.D.

Distinguished Counsel for the Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment

University of California, Los Angeles

Introduction

When the annual U.N. climate conference descends on the small Brazilian rainforest city of Belém in November 2025, it will be tempting to focus on the drama and disunity among major nations. Only 21 countries had even submitted their updated plans for managing climate change by the 2025 deadline required under the Paris Agreement. The U.S. is pulling out of the agreement altogether.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Chinese President Xi Jinping and the likely absence of – or potential stonewalling by – a U.S. delegation will take up much of the oxygen in the negotiating hall.

You can tune them out.

Trust me, I’ve been there. As chair of the California Air Resources Board for nearly 20 years, I attended the annual conferences from Bali in 2007 to Sharm el Sheikh, Egypt, in 2023. That included the exhilarating success in 2015, when nearly 200 nations committed to keep global warming in check by signing the Paris Agreement.

In recent years, however, the real progress has been outside the rooms where the official U.N. negotiations are held, not inside. In these meetings, the leaders of states and provinces talk about what they are doing to reduce greenhouse gases and prepare for worsening climate disasters. Many bilateral and multilateral agreements have sprung up like mushrooms from these side conversations.

This week, for example, the leaders of several state-level governments are meeting in Brazil to discuss ways to protect tropical rainforests that restore ecosystems while creating jobs and boosting local economies.

What States and Provinces Are Doing Now

The real action in 2025 will come from the leaders of states and provinces, places like Pastaza, Ecuador; Acre and Pará, Brazil; and East Kalimantan, Indonesia.

While some national political leaders are backing off their climate commitments, these subnational governments know they have to live with increasing fires, floods and deadly heat waves. So, they’re stepping up and sharing advice for what works.

State, province and local governments often have jurisdiction over energy generation, land-use planning, housing policies and waste management, all of which play a role in increasing or reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Their leaders have been finding ways to use that authority to reduce deforestation, increase the use of renewable energy and cap and cut greenhouse gas emissions that are pushing the planet toward dangerous tipping points. They have teamed up to link carbon markets and share knowledge in many areas.

In the U.S., governors are working together in the U.S. Climate Alliance to fill the vacuum left by the Trump administration’s efforts to dismantle U.S. climate policies and programs. Despite intense pressure from fossil fuel industry lobbyists, the governors of 22 states and two territories are creating policies that take steps to reduce emissions from buildings, power generation and transportation. Together, they represent more than half the U.S. population and nearly 60% of its economy.

Tactics for Fighting Deforestation

In Ecuador, provinces like Morona Santiago, Pastaza, and Zamora Chinchipe are designing management and financing partnerships with Indigenous territories for protecting more than 4 million hectares of forests through a unique collaboration called the Plataforma Amazonica.

Brazilian states, including Mato Grosso, have been using remote-sensing technologies to crack down on illegal land clearing, while states like Amapá and Amazonas are developing community-engaged bioeconomy plans – think increased jobs through sustainable local fisheries and producing super fruits like acaí. Acre, Pará and Tocantins have programs that allow communities to sell carbon credits for forest preservation to companies.

States in Mexico, including Jalisco, Yucatán and Oaxaca, have developed sustainable supply chain certification programs to help reduce deforestation. Programs like these can increase the economic value in some of foods and beverages, from avocados to honey to agave for tequila.

There are real signs of success: Deforestation has dropped significantly in Indonesia compared with previous decades, thanks in large part to provincially led sustainable forest management efforts. In East Kalimantan, officials have been pursuing policy reforms and working with plantation and forestry companies to reduce forests destruction to protect habitat for orangutans.

It’s no wonder that philanthropic and business leaders from many sectors are turning to state and provincial policymakers, rather than national governments. These subnational governments have the ability to take timely and effective action.

Working Together to Find Solutions

Backing many of these efforts to slow deforestation is the Governors’ Climate and Forests Task Force, which California’s then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger helped launch in 2008. It is the world’s only subnational governmental network dedicated to protecting forests, reducing emissions and making people’s lives better across the tropics.

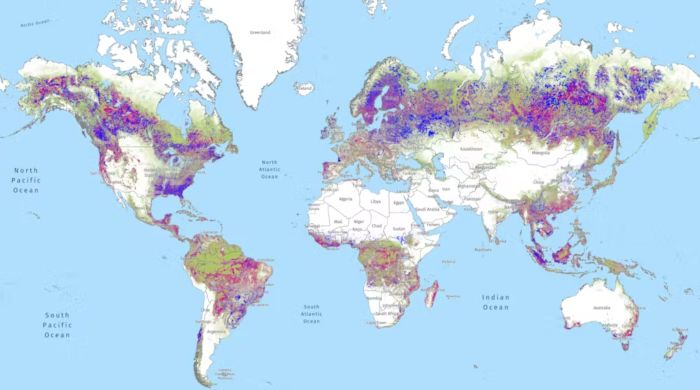

Today, the task force includes 43 states and provinces from 11 countries. They cover more than one-third of the world’s tropical forests. That includes all of Brazil’s Legal Amazon region, more than 85% of the Peruvian Amazon, 65% of Mexico’s tropical forests and over 60% of Indonesia’s forests.

From a purely environmental perspective, subnational governments and governors must balance competing interests that do not always align with environmentalists’ ideals. Pará state, for example, is building an 8-mile (13 kilometer) road to ease traffic that cuts through rainforest. California’s investments in its Lithium Valley, where lithium used to make batteries is being extracted near the Salton Sea, may result in economic benefits within California and the U.S., while also generating potential environmental risks to air and water quality.

Each governor has to balance the needs of farmers, ranchers and other industries with protecting the forests and other ecosystems, but those in the task force are finding pragmatic solutions.

The week of May 19-23, 2025, two dozen or more subnational leaders from Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Indonesia and elsewhere are gathering in Rio Branco, Brazil, for a conference on protecting tropical rainforests. They’ll also be ironing out some important details for developing what they call a “new forest economy” for protecting and restoring ecosystems while creating jobs and boosting economies.

Protecting tropical forest habitat while also creating jobs and economic opportunities is not easy. In 2023, data show the planet was losing rainforest equivalent to 10 soccer fields a minute, and had lost more than 7% since 2000.

But states and cities are taking big steps while many national governments can’t even agree on which direction to head. It’s time to pay attention more to the states.

Originally published by The Conversation, 05.19.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.