A right that must be claimed, defended, and continuously redefined in each generation.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

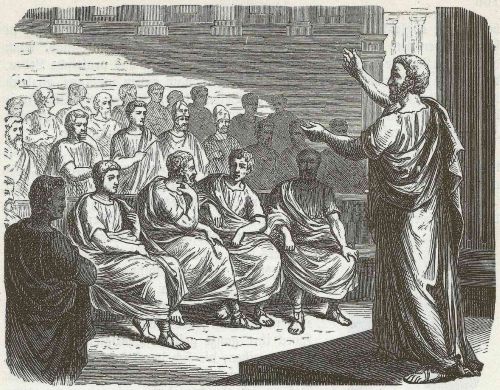

The ancient Greek foundations of free speech were embodied primarily in two powerful and distinct concepts: isegoria and parrhesia. These terms, though often conflated in modern interpretations, represented different but complementary dimensions of what we now call freedom of speech. Isegoria (ἰσηγορία), “equal speech,” was a political principle that emerged most clearly in democratic Athens during the late sixth and fifth centuries BCE. It guaranteed all male citizens the right to speak in the ekklesia, the public assembly where major policy decisions were debated and enacted. This concept was integral to the Athenian democratic ideal, rooted in the belief that political legitimacy depended on the equal participation of citizens in the decision-making process.1 Isegoria functioned as both a right and a mechanism for public deliberation, reinforcing the notion that no single citizen’s voice should hold undue precedence over another’s within the civic sphere.

Greek Foundations: Isegoria and Parrhesia

Parrhesia (παρρησία), usually translated as “frankness,” extended beyond the institutional boundaries of the assembly to encompass a broader ethical and philosophical commitment to truth-telling. Unlike isegoria, which was a procedural right tied to citizenship and the assembly, parrhesia could be exercised in various contexts, including the theater, the courts, philosophical discourse, and even private life. The term connoted a willingness to speak openly and candidly, often in defiance of conventional wisdom or popular opinion. Michel Foucault has argued that parrhesia carried with it a degree of moral risk; the speaker assumed personal danger by speaking truth to power, especially when such truth was unwelcome.2 In this sense, parrhesia was not merely about permission to speak, but about the courage and ethical responsibility to do so honestly. It was celebrated by philosophers like Socrates and Diogenes, who modeled this virtue in their engagements with the public and authority figures.

The practice of parrhesia was vividly illustrated in Athenian drama and philosophical life. Comic playwrights like Aristophanes used the stage as a platform for parrhesiastic critique, often targeting politicians, generals, and even religious practices. In The Clouds, he famously satirized Socrates, while in Lysistrata and The Knights, he ridiculed the Peloponnesian War and its proponents with biting humor.3 These performances were sanctioned by the state and performed during civic festivals, indicating that Athens, for a time, tolerated and even valued such public criticism. However, the limits of this tolerance were exposed in the trial of Socrates in 399 BCE. Although not officially prosecuted for his speech, Socrates’ relentless questioning of authority and his promotion of philosophical inquiry were central to the charges of “impiety” and “corrupting the youth.”4 His execution revealed that while Athens endorsed parrhesia in principle, its practice could become politically explosive when it undermined the foundations of civic and religious consensus.

Philosophers such as Plato and later the Stoics elaborated on parrhesia as an ethical ideal, often contrasting it with sycophancy or rhetorical manipulation. In the Apology, Plato presents Socrates as a paragon of parrhesia, someone who speaks candidly not for applause, but from a sense of divine duty to truth and moral clarity.5 This emphasis on speech as a form of ethical life was further developed by Hellenistic philosophers. The Cynics, such as Diogenes of Sinope, made parrhesia central to their lifestyle, using shameless honesty to challenge social norms and political hypocrisy. Later, the Stoics—particularly Epictetus—framed free speech as a sign of inner freedom, insisting that the wise person must speak the truth fearlessly, regardless of consequence. Thus, in the philosophical tradition, parrhesia evolved from a democratic practice into a model of personal authenticity and virtue, distinct from rhetorical persuasion or institutional privilege.

Taken together, isegoria and parrhesia provided the twin pillars of free speech in ancient Greece—one rooted in civic equality, the other in moral responsibility. Their coexistence highlights the Athenian belief that democratic life depended not only on the legal right to speak, but also on the cultivation of a citizenry willing to speak honestly and thoughtfully. Nonetheless, these ideals were never universally applied. Women, slaves, and metics were excluded from political participation, and even citizens could face punishment if their speech was deemed subversive. The tension between these ideals and their limitations remains relevant today. The ancient Greek experience reveals that free speech is not merely a legal construct but a lived practice, continually shaped by political power, social norms, and ethical commitments. Understanding the Greek origins of these concepts reminds us that freedom of speech has always been both a collective achievement and an individual risk.

Rome: Libertas, Law, and Censorship

The Roman concept of libertas was central to the Republic’s political identity and underpinned Roman ideas about speech and citizenship. Unlike the Greek notion of isegoria, which emphasized equality in public speech, libertas encompassed a broader sense of political and personal autonomy—freedom from domination by a monarch or magistrate. Cicero defined libertas as the condition in which one lives under the law, not the will of another, and for him, the ability to speak freely (libere dicere) was an essential element of civic life.6 In the Senate and law courts, oratory was not only permitted but revered, and prominent statesmen such as Cicero, Cato the Younger, and Julius Caesar built their reputations on rhetorical skill. However, this freedom existed within a highly stratified and oligarchic framework. While senators and elite citizens enjoyed relative latitude in political discourse, the lower classes had few formal venues for public speech, and their expressions of dissent—such as plebeian protests—were often constrained or co-opted by institutional power.

Roman law offered certain protections for speech, particularly in the context of forensic oratory and political debate, but these were far from absolute. The Twelve Tables, Rome’s earliest codified laws (ca. 450 BCE), contained injunctions against slander (maledicere) and the public dissemination of libelous verses—reflecting an early concern for balancing speech with public order and reputation.7 Later legal texts and commentaries reinforced this tension. The jurist Ulpian, writing in the third century CE, acknowledged a limited tolerance for offensive speech if spoken in the heat of passion, but repeated or malicious speech could warrant punishment.8 Moreover, laws against maiestas (treason) expanded dramatically under the Empire, particularly during the reigns of Tiberius and Domitian, when vague accusations of disloyalty could result in execution or exile. Under such regimes, the boundary between free speech and political crime grew dangerously thin, turning legal institutions into instruments of repression rather than protection.

The Roman Republic tolerated a relatively robust culture of political criticism, especially through satire and rhetorical contestation. Writers such as Plautus and Terence in the early Republic, and later Horace and Juvenal in the Imperial period, used theatrical and poetic satire to comment on social mores, corruption, and elite excess. Satire, as a literary genre, became a uniquely Roman medium for indirect parrhesia—a way to veil criticism in wit and ambiguity. However, the satirist’s position was precarious. Juvenal’s biting critiques of imperial decadence had to be cloaked in historical or mythological allusions to avoid reprisal.9 Similarly, the poet Ovid was exiled by Augustus for reasons that remain unclear, though scholars often speculate it was due to the perceived political and moral implications of his Ars Amatoria or an unspecified indiscretion (“carmen et error”).10 These episodes reveal that while artistic expression was nominally free, it remained vulnerable to political sensitivities, especially under the principate when emperors sought to manage public discourse.

Censorship in Rome was institutionalized through the office of the censor, a magistracy established in the mid-fifth century BCE with responsibilities that included conducting the census, overseeing public morality, and maintaining the senatorial rolls. Though not originally conceived as a tool of speech suppression, the censores wielded significant influence over public expression, especially in determining who could speak authoritatively in the Senate and hold office. They could issue nota censoria—moral judgments that damaged reputations and careers. In the Empire, censorship evolved from a civic institution into a more covert and coercive mechanism of imperial control. Augustus pioneered the use of auctoritas (authority) rather than formal censorship to shape cultural output, rewarding compliant writers and punishing dissenters through patronage or exile.11 Later emperors, like Nero and Domitian, were less subtle, targeting authors, philosophers, and senators who dared voice opposition. The public sphere contracted under the weight of imperial paranoia, turning freedom of speech into a dangerous liability.

Roman experiences with free speech, libertas, and censorship illustrate a complex and often contradictory dynamic. In the Republic, speech flourished within elite institutions but was hedged by social hierarchy and legal restriction. Under the Empire, rhetorical and literary expression persisted but became increasingly surveilled and politicized. The ideal of libertas remained a powerful rhetorical motif—invoked by Cicero and revived by Tacitus—but its substance eroded in the face of autocracy. Yet, the Roman tradition left a lasting legacy. Later political theorists, from Renaissance humanists to Enlightenment thinkers, drew on Roman models to articulate ideals of republican liberty and civic discourse. Rome’s history thus provides both a warning and a resource: it shows how free speech can thrive in civic institutions but also how it may be curtailed when power becomes concentrated and intolerant of dissent.12

Near Eastern Contexts: Speech under Kingship and Religion

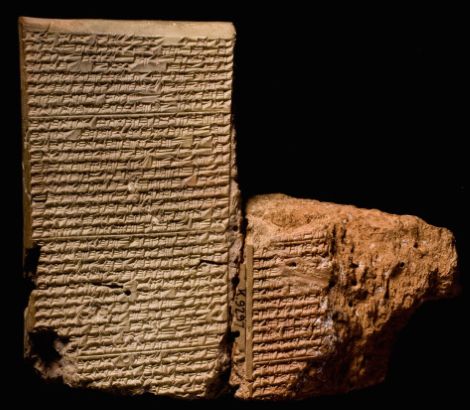

In the ancient Near East, freedom of speech as a formalized legal or political concept did not exist in the same way it later developed in the Greco-Roman world. Instead, speech was framed within a hierarchical structure where kingship and divinely sanctioned authority limited the scope of public expression. Kings, who were often regarded as earthly representatives or even manifestations of the divine, maintained tight control over speech that could be seen as subversive or disrespectful. In Mesopotamian city-states like Ur and Babylon, the king was not merely a political figure but also a judicial and religious one, expected to uphold mīšarum—a concept of justice and social harmony. While royal inscriptions often claimed to represent the voice of truth and justice, dissenting voices were rarely preserved in the textual record, likely due to either suppression or selective archival practices.13 Nevertheless, the presence of literary works such as The Dialogue of Pessimism and The Babylonian Theodicy suggests that philosophical questioning and criticism could be articulated indirectly through fictional or poetic forms.14

These literary texts offer rare glimpses into controlled forms of critical discourse. The Babylonian Theodicy, a dialogic poem written in Akkadian around the late second millennium BCE, stages a conversation between a sufferer and his friend, where the former protests the apparent injustices of the gods and the world.15 Although ultimately reaffirming divine justice, the text daringly gives voice to the questioner’s grievances, including the futility of piety and the suffering of the innocent. The fact that such a text was copied and preserved suggests that elite scribal audiences may have found space within the religious and philosophical tradition for questioning divine order—so long as it remained within a prescribed literary frame. This textual strategy resembles a kind of sanctioned dissent, one that critiques the gods or the cosmos only to reaffirm their authority by the end. It reflects a cautious balance between expression and orthodoxy, shaped by both theological boundaries and political prudence.

In Egypt, similar dynamics prevailed under pharaonic rule. The Pharaoh was considered the physical embodiment of ma’at, the divine principle of truth, order, and justice. As such, his word carried both political and cosmic authority. While direct criticism of the king was unthinkable, certain Middle Kingdom texts reveal an undercurrent of social anxiety and criticism. The Admonitions of Ipuwer, for example, laments a world turned upside down—where the poor have become rich and chaos reigns over order.16 Though the text is often interpreted as royal propaganda intended to justify strong rule, it nonetheless preserves a voice of lament and critique. Egyptian scribal culture permitted, even encouraged, literary exploration of disorder, provided it ultimately served to reinforce the need for centralized authority. This form of controlled expression, mediated through elite literature, suggests that what we might call “free speech” in the ancient Near East was permissible only within circumscribed ideological boundaries.

Religion in the ancient Near East both constrained and enabled speech. Temples were not only religious centers but also major economic and administrative institutions, and priests were among the most literate and powerful members of society. In Sumerian and Akkadian literature, wisdom texts and proverbs often promoted humility in speech, warning against rash words and disrespect toward the gods or superiors. For instance, the Sumerian proverb “Do not speak arrogantly to your god” reflects the underlying principle that speech must always conform to religious decorum.17 Prophets, however, could serve as sanctioned truth-tellers. In the Hebrew Bible, figures like Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Amos spoke out against kings and social injustices with divine authority. Their speech was not “free” in the modern sense, but it derived legitimacy from the claim to be voicing the will of Yahweh rather than personal opinion.18 The prophetic tradition thus allowed a unique space for criticism—contingent on divine endorsement—but also made such speech dangerous and often resisted by the powerful.

While the ancient Near East lacked institutional mechanisms for what modern societies recognize as freedom of speech, it cultivated various forms of expression that allowed for limited critique under the watchful eyes of kings and gods. Speech was always contextual—determined by one’s role in society, the nature of the message, and the medium through which it was conveyed. Scribal literature, religious prophecy, and poetic dialogue became tools through which dissent, ambiguity, or philosophical reflection could be explored without overtly challenging authority. These strategies of indirect speech reveal that intellectual life in the ancient Near East was not devoid of reflection or criticism, but it was profoundly shaped by a cultural matrix in which authority—both divine and royal—was paramount. This environment produced a sophisticated discourse in which speech could probe difficult questions, so long as it did not overtly threaten the prevailing order.

Speech in Religious Traditions: Prophets and Heretics

Throughout ancient religious traditions, speech was a sacred and powerful act—capable of revealing divine will, challenging injustice, or threatening orthodoxy. Prophets, in particular, occupied a paradoxical space: they were often celebrated as truth-tellers yet were also vulnerable to persecution when their messages clashed with religious or political authorities. In the Hebrew Bible, prophets such as Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Amos spoke uncompromising truths about idolatry, economic exploitation, and moral decay. Their words were not protected under any institutional notion of free speech, but they derived authority from the belief that they spoke for God, not themselves. Jeremiah, for instance, was beaten, imprisoned, and thrown into a cistern for his prophecies, which were deemed seditious by the ruling class.19 This dynamic underscores the tension between divine mandate and institutional control—a tension that allowed prophetic speech to flourish, but only within the volatile boundaries of charismatic legitimacy and institutional tolerance.

In Zoroastrianism, the prophet Zoroaster (Zarathustra) similarly challenged established religious norms. Speaking out against the prevailing polytheism of the Iranian plateau, he preached a monotheistic and ethical religion centered on Ahura Mazda and the cosmic struggle between truth (asha) and deceit (druj). Zoroaster’s reformist message likely provoked opposition from the religious and political elites of his time, and tradition holds that he was persecuted before finally gaining the patronage of King Vishtaspa.20 His teachings suggest that prophetic speech could serve a revolutionary function—subverting established priesthoods and dogmas in favor of new religious paradigms. Yet, like the Hebrew prophets, Zoroaster’s ability to speak freely was ultimately contingent upon political support. Without royal patronage, the boundaries of permitted religious speech were sharply constrained, and heterodoxy was typically silenced or absorbed only after political endorsement.

In ancient India, the religious marketplace was especially dynamic, offering space for various forms of speech—even those that directly challenged dominant Vedic orthodoxy. The Buddha, for example, famously rejected the authority of the Vedas and the ritual dominance of the Brahmins, advocating instead for a path based on individual ethical conduct, meditation, and insight. His teachings were revolutionary in their rejection of caste-based spiritual privilege, and yet he avoided persecution in part because of a long-standing Indian tolerance for renunciant traditions and spiritual debate.21 The Buddha’s dialogues (as preserved in the Nikāyas) often present him engaged in vigorous intellectual exchange with Brahmins, ascetics, and laypeople alike. This tradition of debate (vāda) provided a cultural space for philosophical dissent, though later sectarian developments and the formation of Buddhist orthodoxy would, in time, produce their own constraints on religious speech and practice.

By contrast, in ancient Christian traditions, the distinction between prophet and heretic became more sharply defined as ecclesiastical structures solidified. Early Christian communities tolerated a wide variety of teachings—Gnostic, Pauline, Petrine, and Johannine among them—but by the second and third centuries CE, Church authorities began to define orthodoxy more rigorously. Figures such as Marcion and Valentinus, who offered radically different cosmologies and scriptural interpretations, were eventually condemned as heretics.22 While early Christians had once praised their freedom to proclaim truth against Roman persecution, they gradually turned to suppress internal dissent in order to preserve doctrinal unity. The process of canonization and the formation of creeds, such as the Nicene Creed in the fourth century, further narrowed the range of acceptable speech within the Christian community. Thus, the prophetic voice, once a symbol of martyrdom and courage, became increasingly institutionalized and regulated by ecclesiastical hierarchy.

In each of these traditions, prophets and heretics reveal the fraught relationship between religious authority and the spoken word. Prophets were often revered posthumously, once their messages had been absorbed into the religious mainstream, while heretics were cast out or silenced to preserve unity and orthodoxy. Both figures illuminate the limits of tolerated speech in religious communities that prized revelation but feared discord. The institutionalization of religion invariably led to greater control over what could be said and by whom. While ancient traditions did not formally conceptualize freedom of speech, their internal debates and conflicts over prophecy, doctrine, and dissent suggest an enduring concern with the power of language to challenge, destabilize, or renew sacred authority. These traditions laid the groundwork for later theological and philosophical discussions about the boundaries of speech, belief, and conscience.

Comparative Reflections: Ancient Constraints, Modern Echoes

The concept of free speech as a universal human right is a relatively modern invention, but its roots lie in the ancient world’s varied and often precarious experiments with public discourse. In ancient Greece, particularly democratic Athens, the principles of isegoria and parrhesia embodied early attempts to institutionalize open speech. Yet even in this celebrated context, speech was never entirely free. While male citizens enjoyed a degree of freedom in the ekklesia and law courts, that liberty was confined to a small portion of the population and did not extend to women, slaves, or foreigners.23 Moreover, the case of Socrates—executed ostensibly for impiety and corrupting the youth—reveals that even in the birthplace of democracy, challenging core religious and moral assumptions could result in fatal consequences.24 This tension between the promise and limits of speech in Athens finds modern resonance in liberal democracies where legal protections for expression coexist with informal or institutional constraints, particularly in matters of religion, security, or social norms.

Rome, too, provided a complex environment for speech. The ideal of libertas implied not only personal freedom but the right to speak openly in political life. Republican Rome, particularly in the Senate, witnessed fierce oratory and debate, with figures like Cicero extolling libertas as the foundation of Roman greatness. Yet even in the Republic, laws against maiestas (treason) curtailed speech deemed offensive to the state or its leaders, and under the emperors these constraints grew more severe.25 The reign of Tiberius, for example, marked a dark period where speech became suspect, and informers thrived. Despite this, Roman jurisprudence and rhetoric continued to shape modern Western ideals of civic expression and the responsibilities of the speaker. The rhetorical tradition that trained Roman elites in careful, persuasive, and ethically aware speech remains influential in democratic societies today, especially in law, politics, and education.

Ancient Near Eastern and religious traditions offer an alternative view of speech as a sacred and dangerous power. Speech that challenged divine or royal authority was typically forbidden, yet within tightly controlled spaces—such as prophetic utterance or literary dialogues—critical or dissenting voices could emerge. The Hebrew prophets, the Buddha’s discourses, and Zoroaster’s reformist teachings all reflect ancient efforts to speak truth to power under the shield of divine legitimacy. Their stories have profoundly shaped how modern societies view the moral dimension of speech, particularly the courage of those who speak against injustice at personal cost. However, they also illustrate the fragility of such speech in the absence of institutional protections. Contemporary debates about whistleblowers, religious dissent, and moral conscience draw directly—if often unconsciously—on these ancient precedents.26

Modern liberal democracies claim to guarantee freedom of speech, but the boundaries of that freedom remain contested. From social media bans and cancel culture to national security laws and hate speech legislation, the scope of permissible expression is constantly renegotiated. In many ways, these debates echo ancient anxieties: What kinds of speech threaten social order? Who has the right to speak, and who must remain silent? Ancient societies answered these questions differently—through exclusion, divine mandate, or civic privilege—but the core issues endure. Just as parrhesia in Athens required the courage to risk ostracism, modern whistleblowers and activists often speak at great personal cost despite legal protections.27 The legacy of ancient speech cultures reminds us that the freedom to speak has always been intertwined with the willingness to endure consequences.

In reflecting on ancient and modern paradigms of speech, a paradox emerges: the most celebrated speech acts—Socrates before the jury, Cicero in the Senate, Jeremiah denouncing kings, the Buddha challenging Brahmins—occurred under the shadow of repression. Their voices endured not because they were protected but because they were courageous and compelling. Today’s legal frameworks offer more robust defenses for expression, but they cannot eliminate the social, political, and psychological pressures that shape who speaks and who is heard. Thus, the history of free speech is not simply a march toward greater liberty but a continual negotiation between power, truth, and voice. The ancient world, though lacking formal declarations of rights, offers enduring insights into this negotiation—insights that remain urgently relevant in our own contentious public sphere.

Conclusion

To explore freedom of speech in the ancient world is to enter a space of paradox. Societies that extolled open dialogue could also execute their dissenters. Emperors who proclaimed libertas enforced censorship. Prophets who spoke divine truths were imprisoned. And yet, despite all this, individuals continued to speak—boldly, artfully, dangerously.

The ancient legacy of free speech is thus not one of perfect liberty, but of persistent resistance. It reminds us that speech is not only a right but also a responsibility—one that must be claimed, defended, and continuously redefined in each generation.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Josiah Ober, Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rhetoric, Ideology, and the Power of the People (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 112–17.

- Michel Foucault, Fearless Speech, ed. Joseph Pearson (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2001), 14–19.

- Kenneth J. Dover, Aristophanic Comedy (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972), 42–47.

- Robin Waterfield, Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009), 135–42.

- Plato, Apology, in Plato: Complete Works, ed. John M. Cooper (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1997), 17–36.

- Cicero, De Re Publica, trans. Clinton W. Keyes (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1928), 1.49.

- Allan Watson, The Law of the Ancient Romans (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1970), 17–18.

- Ulpian, Digest 47.10.15, in The Digest of Justinian, ed. Alan Watson, vol. 4 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985), 267–68.

- Satires of Juvenal, esp. Satire I, in Juvenal and Persius, trans. Susanna Morton Braund (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 3–7.

- Ovid, Tristia 2.207–212, trans. Peter Green (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

- Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Augustan Rome (London: Bristol Classical Press, 1993), 65–69.

- Quentin Skinner, Liberty Before Liberalism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 27–31.

- Benjamin R. Foster, Before the Muses: An Anthology of Akkadian Literature (Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 2005), 65–66.

- Wilfred G. Lambert, Babylonian Wisdom Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1960), 108–15.

- Ibid., 118–30.

- Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975), 149–63.

- Samuel Noah Kramer, The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963), 252–53.

- Abraham J. Heschel, The Prophets (New York: Harper & Row, 1962), 30–35.

- Jeremiah 38:6–13, in The HarperCollins Study Bible, ed. Harold W. Attridge (New York: HarperOne, 2006).

- Mary Boyce, Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices (London: Routledge, 2001), 19–24.

- Richard Gombrich, What the Buddha Thought (London: Equinox, 2009), 8–12.

- Elaine Pagels, The Gnostic Gospels (New York: Vintage, 1979), 31–44.

Bibliography

- Attridge, Harold W., ed. The HarperCollins Study Bible. New York: HarperOne, 2006.

- Boyce, Mary. Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. London: Routledge, 2001.

- Cicero. De Re Publica. Translated by Clinton W. Keyes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1928.

- Dover, Kenneth J. Aristophanic Comedy. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972.

- Foster, Benjamin R. Before the Muses: An Anthology of Akkadian Literature. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 2005.

- Foucault, Michel. Fearless Speech. Edited by Joseph Pearson. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2001.

- Gombrich, Richard. What the Buddha Thought. London: Equinox, 2009.

- Heschel, Abraham J. The Prophets. New York: Harper & Row, 1962.

- Juvenal and Persius. Satires. Translated by Susanna Morton Braund. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah. The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963.

- Lambert, Wilfred G. Babylonian Wisdom Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1960.

- Lichtheim, Miriam. Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975.

- Ober, Josiah. Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rhetoric, Ideology, and the Power of the People. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Ovid. Tristia. Translated by Peter Green. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

- Pagels, Elaine. The Gnostic Gospels. New York: Vintage, 1979.

- Plato. Plato: Complete Works. Edited by John M. Cooper. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1997.

- Skinner, Quentin. Liberty Before Liberalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Ulpian. The Digest of Justinian, Volume 4. Edited by Alan Watson. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985.

- Waterfield, Robin. Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths. New York: W. W. Norton, 2009.

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. Augustan Rome. London: Bristol Classical Press, 1993.

- Watson, Allan. The Law of the Ancient Romans. Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1970.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.27.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.