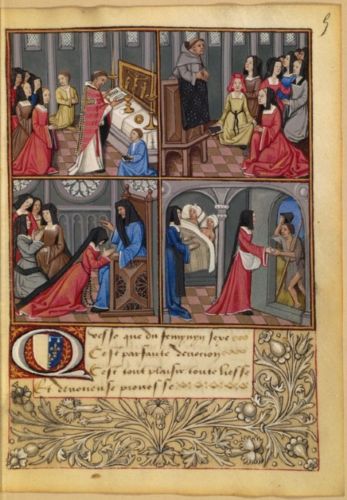

Women were active participants in agriculture, urban crafts, trade, and services.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The position of women in medieval European society was complex, nuanced, and varied significantly based on region, social class, urban versus rural settings, and historical period. While the dominant narrative often emphasizes the subordination of women under patriarchal systems, a closer examination of economic life in the Middle Ages reveals that women played indispensable roles as workers and merchants. Their contributions to the economic fabric of medieval society were multifaceted, extending from domestic production to participation in guilds, trade, and even long-distance commerce. This essay explores the diverse roles women played in the medieval European economy, highlighting their labor contributions, commercial enterprises, legal rights, and limitations, while also challenging oversimplified assumptions about gender roles during this period.

Plows, Profits, and Power: Unraveling Medieval Europe’s Economic Web

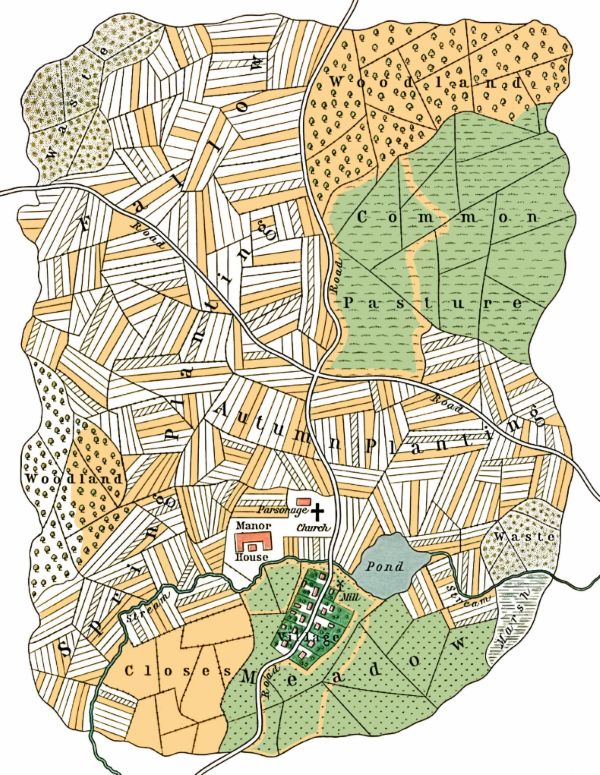

To understand women’s roles in the economy, it is essential to contextualize the broader economic structures of medieval Europe. It was characterized by a deeply stratified and diversified economic landscape that evolved considerably between the early and late Middle Ages. At the heart of the early medieval economy was manorialism, a system rooted in agrarian production and the reciprocal obligations between lords and peasants. Most of the population lived in rural villages and worked on manorial estates where the land was divided into demesne (lord’s land) and peasant holdings. In exchange for access to land, peasants—whether serfs or free tenants—owed labor services, rents, or a combination of both. This localized, subsistence-oriented economy was largely self-sufficient, and long-distance trade was limited in the immediate aftermath of the Western Roman Empire’s collapse. However, even in these early centuries, small-scale barter, village markets, and local fairs enabled the circulation of goods and surplus produce among communities and regions.1

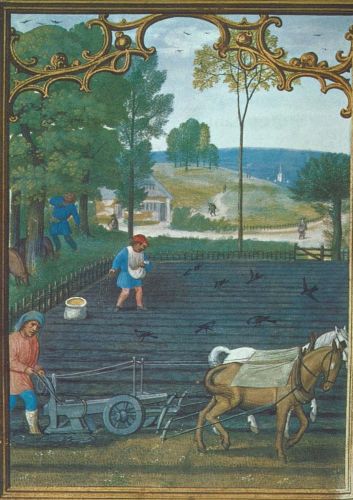

Over time, demographic growth, agricultural innovations, and political stabilization—especially from the 11th century onward—led to significant changes in European economic structures. The adoption of the three-field system, the widespread use of the heavy plough, and improvements in harnessing techniques increased agricultural productivity and allowed for surplus production. This agricultural surplus became the foundation for urban growth and the re-emergence of towns, which began to serve as centers of trade, craft production, and administration. These towns often developed around castles, monasteries, or river crossings and became increasingly autonomous from feudal lords, often acquiring charters of liberty that allowed self-governance and market rights. In this increasingly monetized economy, a burgeoning middle class of merchants and artisans emerged to play a vital role in regional and long-distance commerce.2

The rise of guilds in the 12th and 13th centuries formalized economic activity in towns. Guilds regulated production standards, labor practices, prices, and competition within specific crafts or trades. They also acted as mutual aid societies for their members and wielded significant political influence in municipal governance. While often restrictive and conservative in their regulations, guilds helped stabilize economic practices and ensured the quality of goods. Merchant guilds and, later, craft guilds created a cohesive structure within which medieval townspeople could organize their work and livelihoods. Meanwhile, merchant capitalism flourished in port cities such as Venice, Genoa, and Bruges, where large-scale commercial ventures, investment partnerships (known as commenda), and rudimentary banking institutions emerged. This proto-capitalist economic framework allowed merchants to accumulate wealth and engage in long-distance trade across the Mediterranean, the Baltic, and beyond.3

International commerce also played a growing role in reshaping the medieval economy. The Commercial Revolution of the High Middle Ages saw the expansion of trade routes and the development of new markets across Europe. Italian city-states like Florence and Venice dominated Mediterranean trade, importing luxury goods such as spices, silk, and glassware from the Islamic world and the Byzantine Empire. In northern Europe, the Hanseatic League, a federation of merchant towns, facilitated trade across the North Sea and Baltic, moving goods like wool, timber, salt, and fish. These expanding networks helped link regional economies into a more integrated European marketplace. Trade fairs, particularly in Champagne, France, became crucial hubs for merchants from across the continent. The use of credit instruments like bills of exchange and letters of credit increasingly replaced barter, reflecting a growing sophistication in financial practices and commercial law.4

Despite these developments, the medieval economy remained vulnerable to crises and was marked by persistent inequality. The late 13th and early 14th centuries brought overpopulation, soil exhaustion, and diminishing returns in agriculture, which culminated in the Great Famine (1315–1317). The Black Death (1347–1351) further disrupted economic structures by decimating the population, causing severe labor shortages and economic contraction. Yet paradoxically, these disasters also produced structural changes that, in the long run, benefited survivors. Wages rose due to labor scarcity, and serfdom declined in many regions as peasants gained more bargaining power. This shift, combined with the continuing growth of towns and trade, laid the groundwork for the transition toward a more market-oriented and urban-based economy by the late Middle Ages. In this sense, medieval economic structures were not static but dynamic systems that evolved in response to both innovation and catastrophe.5

Harvesting Silence: Women’s Hidden Hands in Medieval Agrarian Life

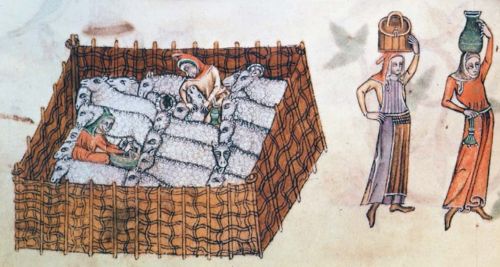

In medieval Europe, women played a central—though often underrecognized—role in agrarian labor, participating in nearly every aspect of rural production. The manorial economy, which dominated much of medieval Europe, relied heavily on peasant labor, and women worked alongside men in the fields, especially during planting and harvest seasons. Women’s agricultural duties included weeding, harvesting grain, threshing, and gleaning—the latter being especially common among poorer women who gathered leftover crops after the primary harvest. These tasks were physically demanding and time-consuming, yet they were essential to the subsistence of peasant households and the economic viability of estates. Despite their substantial contributions, medieval legal and economic texts often overlooked women’s labor, reflecting broader gender biases in historical documentation.6

Female labor was particularly significant within the structure of serfdom, where entire families, not just individual men, were obligated to fulfill labor dues owed to their lords. Manor court rolls and account books from England and elsewhere indicate that women, especially widows and single women, could be held responsible for maintaining plots of land and performing required services, sometimes substituting for absent male relatives.7 Many women participated in collective labor services—such as haymaking or reaping—in exchange for access to land, fuel, or protection. In certain cases, women even acted as heads of households and managed smallholdings, particularly when male relatives were deceased, incapacitated, or away. This autonomy, while constrained by patriarchal norms, reveals that women were not merely supplementary laborers but were embedded in the core structure of medieval rural economies.8

In addition to fieldwork, women engaged in domestic agricultural labor that was vital to peasant survival. Tasks such as dairying, poultry keeping, gardening, and brewing were primarily female responsibilities and had both subsistence and market value. Surplus eggs, butter, cheese, or ale could be sold at local markets or fairs, allowing women to contribute directly to household income. Women also played a central role in processing food, storing grain, and maintaining tools and equipment. These forms of labor, while often dismissed as extensions of household duties, were in fact economically productive and crucial to the survival of rural communities.9 In many regions, such labor was informal and difficult to quantify, which has contributed to the historical invisibility of women’s economic agency.

Religious and legal authorities simultaneously regulated and reinforced gendered labor divisions, though some space for negotiation existed. Canon law, for instance, acknowledged widows’ rights to property and labor in certain contexts, and customary law in many villages permitted women to inherit land or manage tenancies under specific conditions. Though women’s access to land was generally more limited than men’s, they could hold leases or bequeath small plots, particularly in regions like southern France and the Low Countries, where Roman legal traditions had a stronger influence.10 The practice of seasonal labor migration, especially in areas where men sought work outside their communities, also increased women’s responsibilities in managing land and resources, further entrenching their role in agrarian labor networks.

Women’s participation in medieval agrarian labor was both diverse and indispensable, encompassing fieldwork, domestic agriculture, and small-scale production. While shaped by feudal structures and gendered hierarchies, their labor formed the foundation of rural economies across Europe. The marginalization of women in contemporary records has long obscured their contributions, but close readings of manorial documents, wills, and ecclesiastical records reveal a more nuanced reality. Their efforts were critical not only to their own households but also to the functioning of the broader agrarian economy. As recent historiography has demonstrated, any comprehensive understanding of medieval rural life must place women’s labor at the center of the narrative.11

Merchants, Makers, and Mistresses: Women at Work in the Medieval City

The urbanization of Europe during the High and Late Middle Ages opened new opportunities for women’s economic participation beyond the confines of rural life. As towns and cities grew—often around cathedrals, castles, and crossroads—they became vibrant centers of production and commerce. Within these urban economies, women played a significant role, particularly in small-scale trade and craft production. Many women worked as vendors in marketplaces, selling goods such as vegetables, dairy products, cloth, and prepared foods. These roles were often extensions of domestic labor but took on public and commercial significance in the urban setting. Widows and single women, in particular, were frequently active in street markets and stalls, sustaining themselves through this informal but vital segment of the city’s economy.12

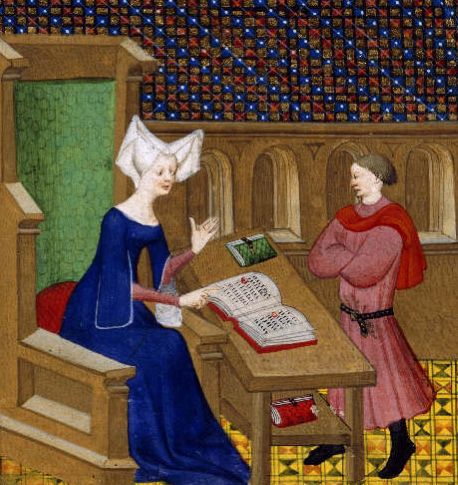

Craft production in medieval towns was typically organized through guilds, which regulated standards, prices, and access to professions. Although guilds were dominated by men, women did participate—sometimes as full members, but more often through informal or semi-official roles. In cities such as Paris, Cologne, and London, records indicate that women worked as seamstresses, silk workers, bakers, brewers, and textile finishers. In some trades, especially those associated with clothing and textiles, women were central to the production process. They frequently worked as assistants, apprentices, or family laborers in their husbands’ workshops. Occasionally, widows could inherit guild memberships or continue operating a workshop under their own names. The flexibility of these arrangements varied widely by region and by the particular guild’s customs and bylaws.13

Beyond their roles in trade and craft, some urban women became successful merchants and entrepreneurs, particularly in port cities and commercial hubs. In places like Venice, Bruges, and Lübeck, women from merchant families sometimes managed import-export businesses, acted as agents in financial transactions, or oversaw household firms. Wealthy widows occasionally invested in real estate or extended credit. Legal frameworks in cities like Florence and Barcelona allowed women—especially those of elite or bourgeois status—to exercise property rights and engage in contractual business, often with male family members serving as legal guarantors. Despite these limitations, urban economic life provided women of means with opportunities for financial autonomy and influence.14 While exceptional, such cases show that women could function as active players in the commercial economies of the Middle Ages, even within patriarchal constraints.

A significant aspect of women’s urban labor involved service work, including domestic service, caregiving, and hospitality. Urban households—particularly those of merchants, clergy, and officials—relied heavily on the labor of female servants. These women often migrated from rural areas in search of work and could comprise a substantial portion of the female urban population. In addition, many women ran or worked in taverns, inns, and bathhouses, which were important social and economic institutions in medieval cities. Some of these establishments were operated by women independently or jointly with spouses, and they served a wide clientele, including travelers, townspeople, and sometimes the clergy. However, such occupations also carried social risks; women working in these venues were frequently subject to moral scrutiny, and some cities imposed regulations to police their behavior, especially where such work overlapped with sex work or challenged gender norms.15

Religious institutions and charitable foundations also played a role in shaping women’s urban economic experiences. Convents offered some women—particularly those from noble or middle-class backgrounds—an alternative economic identity as members of a religious community with collective property and labor. Nunneries produced goods, educated girls, and engaged in land and rent management. In other cases, urban charitable institutions such as hospitals, almshouses, and beguinages employed women as caretakers, nurses, or administrators. These roles offered a measure of economic security and social respectability, especially for unmarried women.16 Collectively, these diverse forms of labor—ranging from market vending to caregiving and entrepreneurship—demonstrate that women in medieval urban economies were not peripheral figures but active participants in the economic life of their communities, albeit often within a framework of legal and cultural constraints.

From Dowry to Dower: Legal Status and Economic Rights of Women

The legal status of women in medieval Europe was shaped by a mosaic of overlapping legal traditions, including Roman law, canon law, feudal custom, and local urban statutes. These systems, often conflicting, determined the parameters of women’s economic and personal autonomy. Under Roman law, which was revived in parts of Europe from the 12th century onward, women were generally considered legally dependent on male guardians (tutela mulierum), yet could still own and manage property under certain conditions. In contrast, Germanic customary law, which persisted in northern and rural areas, often allowed women more informal rights within kin-based structures, particularly concerning movable property and dowries.17 Canon law, promulgated by the Church, reinforced the notion of female subordination within marriage but paradoxically also defended the rights of widows, especially regarding inheritance and dower. The interaction of these legal frameworks created a highly variable landscape in which a woman’s legal identity and economic rights could differ significantly depending on her marital status, location, and social class.¹⁸

Marriage was a critical determinant of a woman’s legal capacity. In most regions, a woman’s legal identity became subsumed under her husband’s through the doctrine of coverture, meaning that married women generally could not enter into contracts, own property independently, or appear in court without their husbands. However, this rule was not universally applied. Urban charters in cities like Barcelona, Paris, and London sometimes carved out exceptions, particularly for businesswomen or women of the merchant class. Widows, in particular, occupied a unique legal category. Upon their husbands’ deaths, they often regained legal independence and could administer estates, sue or be sued, and engage in commerce. In some parts of Europe, such as the Low Countries and parts of southern France, customs even allowed women to inherit land and pass on property in their own name.19 Thus, widowhood, while socially precarious, could also provide a window of legal and economic autonomy.

Dowries and dower rights were among the most significant legal instruments affecting women’s economic position. A dowry was the property a woman brought into a marriage, typically provided by her natal family, while the dower was the portion of her husband’s estate legally reserved for her upon his death. These institutions functioned as both protection and limitation. A large dowry could enhance a woman’s social status and bargaining power within marriage, but it also often became her husband’s to control. Dower rights, however, were typically safeguarded by law; ecclesiastical courts in particular defended a widow’s right to her dower against male relatives or creditors of the deceased.20 These systems were not only expressions of familial and social expectations but also played central roles in structuring women’s ability to accumulate wealth and secure economic stability across generations.

Women’s access to property and credit varied widely across medieval Europe, often reflecting regional legal cultures. In England, for example, common law restricted married women’s economic actions, but through devices like the femme sole status—granted in some urban areas to single or widowed women—limited autonomy was permitted. In parts of Italy and southern France, notarial records show that women frequently participated in financial transactions, such as lending money, leasing land, or entering into apprenticeship contracts.21 The rise of notarial culture in Mediterranean cities, coupled with greater literacy among urban women, helped institutionalize their economic activity and left a rich documentary trail. In the northern commercial centers of Flanders and the Low Countries, women in merchant households often acted as business partners, managing accounts and negotiating trade on behalf of absent or deceased husbands.22 These practices underscore the adaptability of medieval legal structures to economic necessity, even when formal doctrine emphasized male dominance.

While medieval European legal systems imposed numerous constraints on women’s economic agency, the reality was more complex and negotiable. Legal theory often diverged from practice, and women, particularly those in urban or mercantile environments, frequently found ways to assert and exercise economic rights. Widowhood, familial networks, and customary exceptions allowed many women to navigate legal frameworks to their advantage. Nevertheless, these gains were uneven and frequently dependent on social class, geography, and life stage. Recent historiography has highlighted how women’s economic rights in the Middle Ages were not static but evolved in tandem with broader social, economic, and legal transformations.23 A nuanced view of medieval women’s legal and economic status must therefore balance doctrinal restrictions with the pragmatic flexibility evident in daily practice.

Piety and Productivity: Religious and Cultural Boundaries on Women’s Work in Medieval Europe

The pervasive influence of Christianity in medieval Europe profoundly shaped societal attitudes toward women’s labor. The Church was not monolithic in its views, and clerical opinions varied across regions and time periods, but key themes emerged from theological discourse. Rooted in the writings of Church Fathers such as Augustine and Jerome, women were often portrayed as morally weaker and spiritually inferior, which contributed to the perception that their activities—especially outside the home—required regulation and supervision.24 These theological interpretations justified a gendered division of labor, in which a woman’s ideal role was to remain within the domestic sphere, obedient to her husband and dedicated to motherhood and piety. Although work was not inherently sinful, it became suspect when it involved women acting independently or gaining economic power, especially if such activity brought them into public or male-dominated spaces.

Monastic teachings and hagiography further influenced medieval cultural expectations for women. Female saints were often celebrated for their chastity, humility, and withdrawal from worldly concerns—including labor—rather than for their economic contributions. Virgin martyrs, holy anchoresses, and nuns were models of feminine virtue who renounced worldly power and possessions.25 These ideals filtered into secular attitudes and were reflected in cultural productions such as sermons, religious plays, and moral treatises, which often warned against women seeking authority or financial independence. Nevertheless, the Church paradoxically acknowledged the necessity of women’s labor, especially among the poor. Religious writers and preachers tolerated, and occasionally praised, female work when it aligned with perceived virtues such as industriousness, charity, and obedience.26 This ambivalence meant that while women’s work could be morally acceptable, it was always culturally conditioned and subject to scrutiny.

Despite these constraints, the medieval Church also provided institutional spaces where women’s labor could be respected and even sanctified. Convents and beguinages, for example, served as centers of female labor and spirituality. Women in these communities engaged in education, manuscript production, textile work, and healthcare—all seen as extensions of their religious vocation.27 These institutions offered a sanctioned model of women’s labor that combined piety with economic productivity, creating a religious justification for work that would have been discouraged or restricted in secular society. Moreover, charitable labor, such as tending the sick or feeding the poor, was elevated in both religious and lay communities as spiritually meritorious. Thus, although much of the Church’s doctrine emphasized submission and domesticity, its practices often necessitated—and thereby implicitly endorsed—female economic agency under the right conditions.

Secular cultural attitudes, often intertwined with religious beliefs, were equally contradictory. On one hand, medieval literature, popular proverbs, and legal codes reflect a patriarchal worldview that regarded economically active women as threats to social order. Satirical poems, fabliaux, and didactic texts frequently portrayed working women—especially merchants, moneylenders, and tavern keepers—as greedy, shrewish, or sexually immoral.28 These portrayals reinforced social suspicion of women who engaged in public or economically visible roles. On the other hand, regional customs and economic necessity tempered these views. In towns and cities, especially in northern Europe, it was not uncommon for women to manage shops, participate in local markets, or oversee estates in the absence of their husbands. While culture often condemned such independence in theory, in practice it was both necessary and, at times, respected.

Ultimately, the interplay between religion and cultural attitudes created a framework of conditional acceptance for women’s labor. Work that reinforced gender norms—such as spinning, weaving, nursing, or baking—was more likely to be socially tolerated or even honored. Conversely, labor that blurred gender lines or suggested female autonomy—like money lending, running businesses, or speaking in public—was stigmatized.29 The medieval worldview was not static; it evolved with demographic shifts, economic demands, and religious reforms. The Black Death, for example, opened temporary opportunities for women to assume roles traditionally occupied by men, leading to momentary reevaluations of gender and labor. Nevertheless, cultural and religious norms remained powerful forces that both constrained and shaped the roles women could occupy in the medieval economy.

Conclusion

The economic life of women in medieval Europe was rich and varied. Far from being mere appendages to male labor, women were active participants in agriculture, urban crafts, trade, and services. Their roles as workers and merchants, while often circumscribed by legal and cultural barriers, reveal significant agency and adaptability. Though frequently overshadowed in traditional historical narratives, the economic contributions of medieval women were essential to the survival and prosperity of communities across Europe. Acknowledging their labor reshapes our understanding of gender, economy, and society in the medieval world, and calls for a more inclusive historical perspective that honors the complexity of women’s lives in the past.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Marc Bloch, Feudal Society: Vol. 1, The Growth of Ties of Dependence, trans. L.A. Manyon (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961), 59–73.

- Georges Duby, Rural Economy and Country Life in the Medieval West, trans. Cynthia Postan (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998), 132–151.

- Steven A. Epstein, An Economic and Social History of Later Medieval Europe, 1000–1500 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 78–85.

- Robert S. Lopez, The Commercial Revolution of the Middle Ages, 950–1350 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 45–61.

- John Aberth, An Environmental History of the Middle Ages: The Crucible of Nature (London: Routledge, 2013), 179–193.

- Judith M. Bennett, Women in the Medieval English Countryside: Gender and Household in Brigstock before the Plague (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 34–41.

- Barbara A. Hanawalt, The Ties That Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 89–93.

- Shulamith Shahar, The Fourth Estate: A History of Women in the Middle Ages, trans. Chaya Galai (London: Methuen, 1983), 105–108.

- Jane Tibbetts Schulenburg, Forgetful of Their Sex: Female Sanctity and Society, ca. 500–1100 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 212–215.

- Judith M. Bennett and Ruth Mazo Karras, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Women and Gender in Medieval Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 266–270.

- Eileen Power, Medieval Women (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1929), 74–80.

- Martha C. Howell, Women, Production, and Patriarchy in Late Medieval Cities (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 18–24.

- Caroline Barron, “The Regulation of Trade and the Role of Women in the Medieval Economy,” Historical Research 70, no. 173 (1997): 125–127.

- Bennett, Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England, 91-96.

- Sharon Farmer, Surviving Poverty in Medieval Paris: Gender, Ideology, and the Daily Lives of the Poor (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2002), 112–119.

- Walter Simons, Cities of Ladies: Beguine Communities in the Medieval Low Countries, 1200–1565 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 75–80.

- Susan Mosher Stuard, Women in Medieval Society (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1976), 14–19.

- James A. Brundage, Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 324–330.

- Jo Ann McNamara and Suzanne Wemple, “The Power of Women Through the Family in Medieval Europe: 500–1100,” Feminist Studies 1, no. 3/4 (1973): 126–127.

- Barbara Hanawalt, The Wealth of Wives: Women, Law, and Economy in Late Medieval London (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 77–80.

- Judith C. Brown and Robert C. Davis, eds., Gender and Society in Renaissance Italy (London: Longman, 1998), 43–47.

- Howell, Women, Production, and Patriarchy in Late Medieval Cities, 102-108.

- Bennett, Judith M. “History That Stands Still: Women’s Work in the European Past.” Feminist Studies 14, no. 2 (1988): 269–283.

- Caroline Walker Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 15–18.

- Schulenburg, Forgetful of Their Sex, 52-58.

- Dyan Elliott, Spiritual Marriage: Sexual Abstinence in Medieval Wedlock (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 113–117.

- Simons, Cities of Ladies, 144-150.

- Judith M. Bennett, Medieval Women in Modern Perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 62–66.

- Shahar, The Fourth Estate, 89-92.

Bibliography

- Aberth, John. An Environmental History of the Middle Ages: The Crucible of Nature. London: Routledge, 2013.

- Barron, Caroline. “The Regulation of Trade and the Role of Women in the Medieval Economy.” Historical Research 70, no. 173 (1997): 123–132.

- Bennett, Judith M. Women in the Medieval English Countryside: Gender and Household in Brigstock before the Plague. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Bennett, Judith M. Medieval Women in Modern Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Bennett, Judith M., and Ruth Mazo Karras, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Women and Gender in Medieval Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Bloch, Marc. Feudal Society: Vol. 1, The Growth of Ties of Dependence. Translated by L.A. Manyon. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961.

- Brown, Judith C., and Robert C. Davis, eds. Gender and Society in Renaissance Italy. London: Longman, 1998.

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

- Duby, Georges. Rural Economy and Country Life in the Medieval West. Translated by Cynthia Postan. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998.

- Elliott, Dyan. Spiritual Marriage: Sexual Abstinence in Medieval Wedlock. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Epstein, Steven A. An Economic and Social History of Later Medieval Europe, 1000–1500. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Farmer, Sharon. Surviving Poverty in Medieval Paris: Gender, Ideology, and the Daily Lives of the Poor. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2002.

- Hanawalt, Barbara A. The Ties That Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Hanawalt, Barbara. The Wealth of Wives: Women, Law, and Economy in Late Medieval London. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Howell, Martha C. Women, Production, and Patriarchy in Late Medieval Cities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

- Lopez, Robert S. The Commercial Revolution of the Middle Ages, 950–1350. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- McNamara, Jo Ann, and Suzanne Wemple. “The Power of Women Through the Family in Medieval Europe: 500–1100.” Feminist Studies 1, no. 3/4 (1973): 126–141.

- Power, Eileen. Medieval Women. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1929.

- Schulenburg, Jane Tibbetts. Forgetful of Their Sex: Female Sanctity and Society, ca. 500–1100. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- Shahar, Shulamith. The Fourth Estate: A History of Women in the Middle Ages. Translated by Chaya Galai. London: Methuen, 1983.

- Simons, Walter. Cities of Ladies: Beguine Communities in the Medieval Low Countries, 1200–1565. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

- Stuard, Susan Mosher. Women in Medieval Society. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1976.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.28.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.