The Industrial Revolution gave rise to some of the most egregious labor abuses in the nation’s history.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The American Industrial Revolution, spanning roughly from the late 18th century through the early 20th century, was a period of profound transformation. It ushered in unprecedented economic growth, technological innovation, and urban expansion. Factories, railroads, and mechanized agriculture revolutionized the means of production and increased the nation’s wealth. However, this progress came at a steep human cost. Beneath the glossy veneer of industrial prosperity lay a dark undercurrent of labor exploitation. The rapid shift from agrarian to industrial labor created a vast working class subjected to dire conditions, minimal legal protections, and systemic abuse. Labor abuses during the Industrial Revolution in America were pervasive and multifaceted, encompassing long hours, unsafe working environments, child labor, gender discrimination, and the suppression of labor organization efforts.

The Nature of Industrial Work

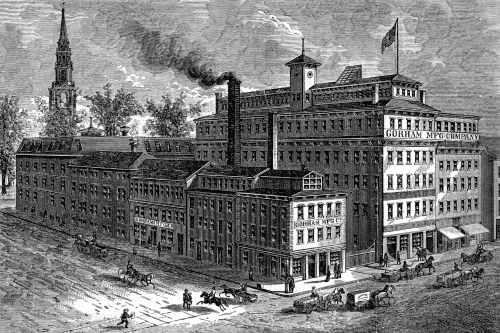

The shift from artisanal and agrarian labor to factory work marked a significant transformation in American labor patterns. Prior to industrialization, many Americans worked on farms or in small family-run businesses, where the rhythm of labor was often tied to natural cycles and personal discretion. Industrialization, however, imposed a rigid, clock-driven schedule that prioritized production over well-being.1

Factory labor was characterized by monotonous, repetitive tasks often performed for 10 to 16 hours a day, six days a week. Workers were typically paid by the piece or by the hour, and wages were meager, often insufficient to support a family.2 Factory owners justified low pay and long hours with the belief that laborers were replaceable and unskilled. The mechanization of labor devalued individual craftsmanship, reducing workers to mere cogs in the industrial machine.

Conditions within factories, mills, and mines were deplorable. Poor ventilation, inadequate lighting, and the constant presence of dangerous machinery made injuries commonplace.3 There were no standards for workplace safety, and employers bore no responsibility for accidents. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911, which claimed the lives of 146 garment workers—mostly immigrant women and girls—highlighted the lethal consequences of unregulated industrial workplaces.4

Child Labor

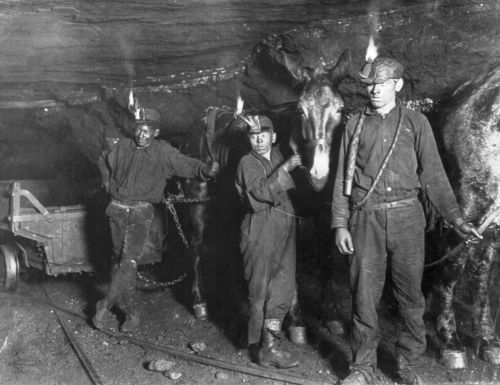

One of the most egregious aspects of labor exploitation during the Industrial Revolution was the widespread use of child labor. Children as young as five were employed in factories, mines, and textile mills. Employers favored children because they could be paid less, were more compliant, and could access small spaces in machinery or underground.5

Children worked grueling hours—often the same as adults—with minimal breaks and no access to education. In textile mills, they inhaled cotton fibers that led to chronic respiratory conditions.6 In coal mines, they performed the backbreaking and dangerous work of “breaker boys,” sorting coal and clearing debris, frequently under the threat of physical punishment for mistakes or slow performance.

Although some reformers, such as Lewis Hine and members of the National Child Labor Committee, exposed the horrors of child labor through photography and investigative reporting,7 meaningful change was slow. It wasn’t until the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 that significant restrictions on child labor were codified into federal law.8

Immigrant and Minority Labor

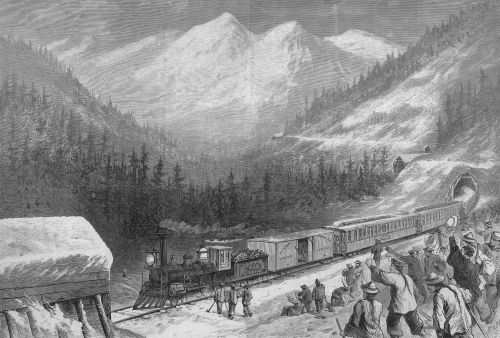

The labor abuses of the Industrial Revolution disproportionately affected immigrants and racial minorities. Waves of immigrants from Ireland, Italy, Eastern Europe, and later China and Mexico provided a steady supply of cheap labor. These groups were often segregated into the most menial and dangerous jobs, facing both workplace exploitation and social discrimination.9

Chinese laborers, for instance, were instrumental in building the transcontinental railroad but were subjected to extreme racism, low wages, and perilous working conditions.10 African American workers, freed after the Civil War, found few opportunities outside of sharecropping in the South or low-paid industrial labor in the North.11 Racial segregation in unions and hiring practices ensured that non-white workers remained at the bottom of the labor hierarchy.

Women, too, faced unique challenges. Female factory workers were often paid significantly less than their male counterparts, even for equivalent work. They were expected to perform domestic labor in addition to industrial labor, and they were routinely subjected to sexual harassment and exploitation by male supervisors.12 The concept of the “working woman” was stigmatized, despite women forming a substantial part of the industrial workforce, particularly in textiles and garment manufacturing.

Resistance and the Labor Movement

Despite these hardships, the American working class did not remain passive. Labor resistance began to coalesce in the form of strikes, mutual aid societies, and eventually labor unions. Early labor movements such as the Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor (AFL) sought to organize workers across industries and advocate for better wages, hours, and conditions.13

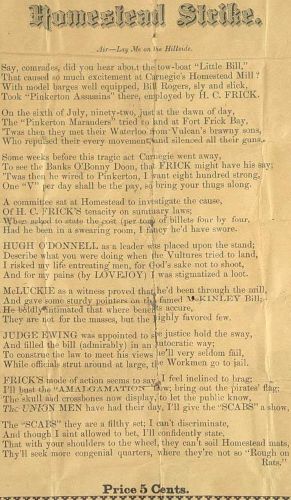

Labor organizing was often met with violent opposition. The Haymarket Affair of 1886, a peaceful rally in Chicago that turned deadly after a bomb was thrown at police, led to a national crackdown on labor radicals.14 The Pullman Strike of 1894 and the Homestead Strike of 1892 likewise ended in bloodshed and the suppression of union efforts.15

Private security forces like the Pinkertons were frequently employed to break strikes, and state militias were called in to suppress worker uprisings. Courts issued injunctions against union activity, and workers were blacklisted for participating in organizing efforts. Yet over time, persistent activism bore fruit. The establishment of the eight-hour workday, the legalization of unions, and the passage of labor laws in the 20th century were direct results of these early struggles.16

The Legacy of Labor Abuses

The legacy of labor abuses during the Industrial Revolution continues to shape American labor law and worker protections. The abuses of the period laid bare the consequences of unchecked capitalism and the necessity of government intervention in the labor market. Progressive Era reformers, influenced by the suffering of industrial workers, advocated for sweeping changes that culminated in landmark legislation such as the Fair Labor Standards Act, the National Labor Relations Act, and the Occupational Safety and Health Act.17

Moreover, the historical memory of labor exploitation has fueled subsequent social movements advocating for civil rights, gender equality, and economic justice. The fight for a living wage, paid family leave, and workplace equity draws on the same themes that animated labor struggles during the Industrial Revolution.

Conclusion

The Industrial Revolution in America was a period of remarkable innovation and growth, but it also gave rise to some of the most egregious labor abuses in the nation’s history. Exploited workers—men, women, and children—bore the burden of industrial progress under harsh and often inhumane conditions. Their struggles, sacrifices, and resistance helped shape a modern labor movement and brought about crucial reforms. Understanding this history is essential not only to honoring those who toiled and suffered but also to ensuring that the pursuit of progress never again comes at the expense of basic human dignity and rights.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Joshua B. Freeman, Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World (New York: W. W. Norton, 2018), 45.

- Walter Licht, Industrializing America: The Nineteenth Century (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 61.

- David Von Drehle, Triangle: The Fire That Changed America (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2003), 38–41.

- Von Drehle, Triangle, 72–75.

- Hugh D. Hindman, Child Labor: An American History (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2002), 57.

- Hindman, Child Labor, 60–63.

- Alexander Nemerov, Lewis Hine: Photographer of Americans (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2002), 44.

- U.S. Department of Labor, Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/flsa.

- John Bodnar, The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985), 101.

- Erika Lee, At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 87.

- Jacqueline Jones, Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family from Slavery to the Present (New York: Basic Books, 1985), 113–16.

- Alice Kessler-Harris, Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 96–99.

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, vol. 1 (New York: International Publishers, 1947), 289.

- James R. Green, Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement and the Bombing That Divided Gilded Age America (New York: Pantheon, 2006), 154–59.

- Richard White, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America (New York: W. W. Norton, 2011), 323.

- Melvyn Dubofsky, Industrialism and the American Worker, 1865–1920 (Arlington Heights, IL: Harlan Davidson, 1996), 108–10.

- David Brody, Workers in Industrial America: Essays on the Twentieth Century Struggle (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 137–42.

Bibliography

- Bodnar, John. The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985.

- Brody, David. Workers in Industrial America: Essays on the Twentieth Century Struggle. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Dubofsky, Melvyn. Industrialism and the American Worker, 1865–1920. Arlington Heights, IL: Harlan Davidson, 1996.

- Foner, Philip S. History of the Labor Movement in the United States. Vol. 1. New York: International Publishers, 1947.

- Freeman, Joshua B. Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World. New York: W. W. Norton, 2018.

- Green, James R. Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement and the Bombing That Divided Gilded Age America. New York: Pantheon, 2006.

- Hindman, Hugh D. Child Labor: An American History. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2002.

- Jones, Jacqueline. Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family from Slavery to the Present. New York: Basic Books, 1985.

- Kessler-Harris, Alice. Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Lee, Erika. At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- Licht, Walter. Industrializing America: The Nineteenth Century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995.

- Nemerov, Alexander. Lewis Hine: Photographer of Americans. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2002.

- U.S. Department of Labor. Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/flsa.

- Von Drehle, David. Triangle: The Fire That Changed America. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2003.

- White, Richard. Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America. New York: W. W. Norton, 2011.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.28.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.