Humanity has always lived in the shadow—and under the influence—of changing skies.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Long before the modern scientific consensus on anthropogenic climate change, ancient thinkers were already observing and theorizing about the relationship between environmental conditions and human life. Among these early intellectuals, Aristotle, Vitruvius, and Shen Kuo stand out for their writings that, while not addressing climate change as we define it today, reflect a keen awareness of climatic variation and its broader implications. Aristotle, in works such as Meteorologica, explored weather patterns and environmental zones, linking them to the habits and characteristics of different peoples. Vitruvius, the Roman architect and engineer, emphasized in De Architectura how climate influenced urban planning, health, and architectural design. Centuries later, the Chinese polymath Shen Kuo documented geological and climatic changes with a scientific curiosity that foreshadowed later environmental thought. Though separated by time and geography, all three shared a proto-scientific concern with how shifting natural conditions affect human society—an intellectual legacy that resonates in contemporary conversations about climate change.

Aristotle and Climatic Zones

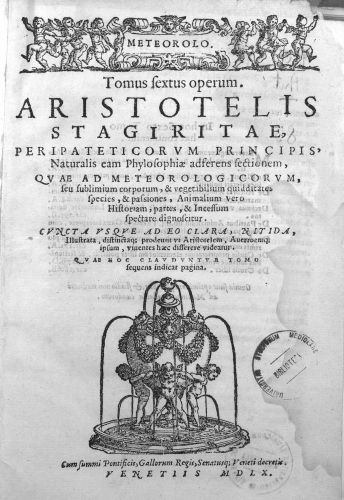

Aristotle’s investigations into natural phenomena laid early foundations for what would become scientific discourse on climate and environmental patterns. His most significant work on these topics appears in Meteorologica, where he sought to explain atmospheric processes in a rational and systematic manner. Aristotle did not consider climate change in the modern sense of long-term, human-driven shifts, but he was deeply concerned with the natural variability of weather and regional climates. He recognized patterns in winds, rains, and temperature, attributing them to the movements and interactions of the four classical elements—earth, air, fire, and water. His theory of exhalations—dry and moist vapors rising from the Earth—was central to his explanation of weather phenomena, including the formation of clouds, winds, and precipitation.1 Though lacking our contemporary tools and data, Aristotle’s attempts to generalize about climatic zones and their characteristics reflect a proto-climatological method.

Aristotle also categorized the Earth into three major climatic zones: the frigid zones near the poles, the torrid zone near the equator, and the temperate zones lying in between. This tripartite division helped him theorize about the suitability of different regions for human habitation and political development. In Politics, he linked climate to the disposition and capabilities of peoples, asserting, for example, that those in temperate zones were the most balanced in character and thus best suited for cultivating civic life.2 These theories exhibit a deterministic streak—suggesting that environmental conditions directly influence human behavior and societal organization. While today such views are rightly challenged for their reductionism, they represent one of the earliest attempts to tie climate to sociopolitical outcomes, a theme that recurs in later environmental and geographical thought.

Importantly, Aristotle also recognized that climatic conditions were not entirely static. He made passing references to local changes in geography and weather patterns, which he attributed to both natural and human causes. For instance, he noted that the silting of rivers and the drainage of marshes could change the local climate over time.3 Although Aristotle did not conceptualize these changes on a planetary scale, his awareness that environmental conditions could shift, and that such shifts had practical consequences, shows a sensitivity to ecological transformation. His recognition of anthropogenic landscape changes affecting local weather patterns is an important antecedent to later environmental studies and even the modern notion of localized climate impacts.

Aristotle’s approach to climate was fundamentally holistic, integrating observations of weather with broader theories of nature and the cosmos. He believed that understanding the heavens and the Earth required a unified natural philosophy, where climate phenomena were linked to astronomy, physics, and biology. In Meteorologica, he connected seasonal changes to celestial cycles, particularly the sun’s motion along the ecliptic, and how these influenced rainfall and winds.4 This cosmological framing underscores how climate, in Aristotle’s worldview, was deeply embedded in a broader metaphysical order. Such a perspective contrasts sharply with today’s data-driven climate science, yet it illustrates how ancient thinkers sought explanatory coherence across domains of natural inquiry.

Ultimately, Aristotle’s reflections on climate, though grounded in pre-modern cosmology, reveal a remarkably perceptive effort to make sense of environmental regularities and their social ramifications. While he lacked the concept of global warming or carbon emissions, his writings exhibit an awareness of climatic variation, regional differentiation, and even human influence on environmental conditions. His method—blending empirical observation with theoretical speculation—set a precedent for future natural philosophers.5 For scholars tracing the genealogy of climate thought, Aristotle represents a critical early voice, framing the environment not as a static backdrop to human activity but as an active and mutable force in shaping civilization.

Building on Vitruvius

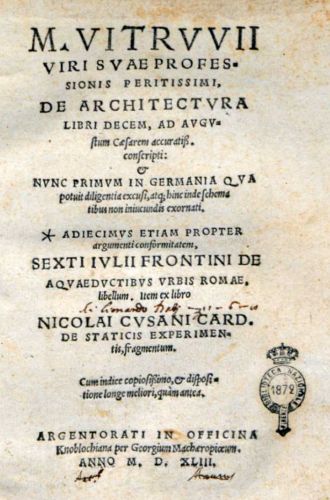

In De Architectura, Vitruvius presents a comprehensive vision of architecture that is deeply responsive to the natural environment, particularly to climate and geography. Though he did not speak of “climate change” in the modern, long-term, global sense, he repeatedly emphasized that different climates demanded different architectural responses—a recognition of regional environmental variability. In Book I, he lays out the principle that architecture must be informed by nature, “so that healthy conditions may result from the choice of site and orientation.”6 This environmental determinism shaped his belief that buildings, cities, and even the bodies of their inhabitants were affected by air quality, prevailing winds, and exposure to sunlight. His architectural theory thus hinged on the understanding that climate was not uniform and that designing with climate in mind was essential for the well-being of individuals and the longevity of human settlements.

Vitruvius offered detailed guidance on selecting city sites based on climate and prevailing winds. In Book I, Chapter 4, he explains how winds vary according to geography and topography, and how exposure to particular wind directions could cause illness or discomfort if not properly accounted for. He even prescribed angling city streets to deflect cold and harmful winds—an early recognition of what might be called microclimatic planning.7 Though he did not articulate a dynamic model of climate variation over time, his writing reveals a nuanced understanding of climatic diversity across space and its architectural implications. For Vitruvius, the environment was not static but rather something to be studied, interpreted, and adapted to. His geographical awareness of winds and weather phenomena reflects an empirical sensibility that places him at the forefront of environmentally responsive urban planning in antiquity.

Moreover, Vitruvius tied climate directly to human physiology and culture. In Book VI, he advances a theory that different climates produce different human characteristics. He argues that those living in northern, colder climates are physically stronger but intellectually less agile, while those in southern, hotter regions are more mentally acute but physically weaker.8 This theory, echoing elements of Hippocratic medicine and Aristotelian thought, positioned climate as a determinant not only of architectural form but also of cultural and racial attributes. While this environmental determinism has been critiqued for its simplistic correlations, it illustrates Vitruvius’s broader view that climate shapes civilization. He believed that successful societies and structures were those that harmonized with their environments, which were understood to be inherently diverse and subject to variation.

Though he did not explore long-term climate change, Vitruvius did recognize that environmental and topographical features could shift due to natural or human activity. He discusses, for example, the importance of understanding soil quality and water sources, noting how rivers can change course, springs can dry up, and marshes can form where once there was dry land.9 These observations, while framed primarily in terms of site planning, reflect a nascent awareness of landscape change and its impact on human habitation. Such changes, in turn, could subtly alter local climatic conditions—warmer air in cleared areas, stagnant humidity near marshes, and cooling near water bodies. This attentiveness to dynamic landscapes hints at an early understanding of the interconnectedness between environment and human intervention, though it stops short of a full theory of anthropogenic climate change.

Vitruvius’s lasting contribution lies in his insistence that climate and environment are essential considerations in architecture and urbanism. His methodical approach, integrating observation, empirical reasoning, and theoretical reflection, offers a holistic framework for understanding how built environments must respond to natural forces.10 In doing so, Vitruvius helped establish a tradition of environmental design that resonates with modern sustainable architecture. While his era lacked the concept of global climate systems or the anthropogenic impact on them, his emphasis on climatic responsiveness and regional adaptation constitutes a significant early engagement with environmental thinking. His work remains a vital historical resource for tracing the evolution of climate-conscious planning from antiquity to the present.

Pool Dreams with Shen Kuo

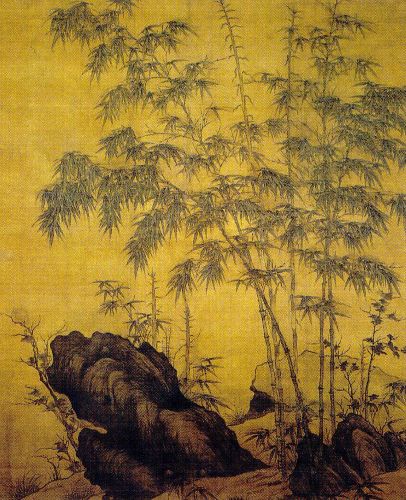

Shen Kuo (1031–1095), a polymath of China’s Northern Song dynasty, made significant contributions to early scientific thinking through his encyclopedic work, Dream Pool Essays (Mengxi Bitan). Among his many investigations, Shen recorded a series of empirical observations about environmental and geological phenomena that suggest a keen awareness of what we would now call climate variability. Though he did not articulate a unified theory of climate change in the modern sense, he did describe climatic anomalies, long-term environmental shifts, and geological transformations with remarkable insight. For instance, Shen noted changes in the position of rivers, the erosion and deposition of soil, and fossilized bamboo found in places far north of where bamboo normally grows.11 These examples demonstrate his understanding that the Earth’s surface and climate could alter significantly over time, challenging prevailing cosmological assumptions about a static, unchanging natural world.

One of the most cited examples of Shen Kuo’s proto-climatological insight is his account of fossilized bamboo discovered in the dry, northern region of Yanzhou, an area where bamboo could not then grow due to cold conditions. Shen hypothesized that the region must have once experienced a warmer climate that could support such vegetation.12 Rather than attributing this anomaly to a miraculous event or rejecting it as an error, he proposed a naturalistic explanation based on environmental change over geological time. This inference—that climates can shift and alter the biosphere of a given region—anticipates key ideas later developed in the earth sciences. While Shen did not speculate on the mechanisms driving such climatic shifts, his ability to connect geological and botanical evidence to climatic inference marks a sophisticated empirical methodology for his time.

Shen’s work also reflects an appreciation for the role of long-term environmental processes in shaping the physical world. In a passage describing how heavy rains could cause landslides and change the course of rivers, he draws attention to the cumulative power of slow-moving natural forces.13 This interest in gradual transformation rather than sudden catastrophe places Shen in the intellectual company of later thinkers such as James Hutton and Charles Lyell, who would pioneer geological uniformitarianism centuries later. Shen’s reflections suggest that climate and geography were not immutable, and that environmental forces shaped the world over extended periods. Although his observations were piecemeal rather than systematic, they illustrate a dynamic conception of nature—one in which both climate and terrain were subject to flux.

Moreover, Shen frequently engaged with the question of human interaction with the environment. He documented cases where irrigation, deforestation, and agricultural practices appeared to impact local ecological conditions.14 His recognition that human activities could exacerbate flooding, soil degradation, or microclimatic changes illustrates a nascent understanding of anthropogenic environmental effects. Though he did not describe a global or large-scale human impact on climate, his acknowledgment of human influence on environmental systems aligns with the broader theme in his work: that nature and human society are deeply interwoven. This holistic perspective reveals an early framework for what we might now call environmental history, where natural and human forces jointly shape the trajectory of change.

Shen Kuo’s Dream Pool Essays thus offers a rare and valuable pre-modern lens on environmental variability. While his framework was still shaped by traditional Chinese cosmology and lacked the formal scientific structures developed in Enlightenment Europe, his empirical approach, critical reasoning, and observational acumen distinguish him as an early pioneer in environmental science.15 His descriptions of past climate conditions, geological time, and anthropogenic landscape changes place him in the lineage of thinkers who have questioned the constancy of nature. For modern historians of climate science, Shen Kuo represents a significant voice from outside the Greco-Roman tradition—a testament to the global roots of environmental thought and a reminder that awareness of climatic change long predates the industrial era.

Conclusion

The writings of Aristotle, Vitruvius, and Shen Kuo collectively offer a remarkable window into premodern understandings of climate and environmental variability. Though each thinker operated within distinct intellectual traditions—Greek, Roman, and Chinese respectively—they shared a commitment to observing nature and theorizing its influence on human life. Aristotle approached climate as part of a larger cosmological system, positing that environmental factors shaped both physical phenomena and the political temperament of peoples. Vitruvius extended this environmental determinism into practical architectural design, insisting that buildings and cities must respond to local climatic conditions for health and harmony. Shen Kuo, operating with an empirical bent characteristic of Song dynasty science, documented specific instances of environmental change, including fossil evidence and human impacts on landscape, suggesting an early recognition that climates and ecosystems could shift over time.

What unites these three thinkers is not a fully developed theory of climate change as we understand it today, but rather an awareness that the environment is neither fixed nor inert. All three recognized, in various ways, that natural forces—whether atmospheric, geological, or biological—interact with human systems in complex and sometimes unpredictable ways. Aristotle’s notion of exhalations, Vitruvius’s city-planning principles based on wind and sun, and Shen Kuo’s observations of fossilized flora in climatically implausible regions all reflect efforts to grapple with environmental variability over space and time. These early insights laid important conceptual groundwork for later developments in climatology, geography, and environmental science.

Their respective works also demonstrate that concern for the relationship between humans and their environments is not a modern invention but a deep-rooted intellectual tradition. Each thinker emphasized that understanding climate was crucial not only for interpreting the natural world but also for making decisions in governance, design, agriculture, and health. While their explanations were framed by the limitations of their eras, their underlying questions remain urgent today: How does climate shape the human experience, and how might human actions, in turn, reshape climate and landscape?

In revisiting the contributions of Aristotle, Vitruvius, and Shen Kuo, we see the early contours of a global history of environmental thought—one that stretches across continents and centuries. Their writings reflect an embryonic climate consciousness, grounded in empirical observation, philosophical reflection, and a sense of the profound entanglement between nature and culture. Recognizing this intellectual heritage enriches our understanding of the long arc of climate awareness and reminds us that current conversations about climate change are not unprecedented but rather the latest chapter in a very old story.

Thus, while these ancient and medieval scholars could not have foreseen anthropogenic climate change, their work underscores a timeless truth: humanity has always lived in the shadow—and under the influence—of changing skies.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Aristotle, Meteorologica, trans. H. D. P. Lee (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1952), I.3–I.4.

- Aristotle, Politics, trans. Carnes Lord (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), VII.7, 1327b.

- Aristotle, Meteorologica, II.3.

- Ibid., I.9–I.11.

- Daryn Lehoux, What Did the Romans Know?: An Inquiry into Science and Worldmaking (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 45–48.

- Vitruvius, De Architectura, trans. Ingrid D. Rowland and Thomas Noble Howe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), I.1.2.

- Ibid., I.6.5–7.

- Ibid., VI.1.10–13.

- Ibid., VIII.1.1–4.

- Lisa Landrum, “Vitruvius and the Environment: Reconsidering Climate in Classical Architecture,” Journal of Architectural Historiography 27, no. 1 (2015): 34–37.

- Shen Kuo, Dream Pool Essays (Mengxi Bitan), trans. Joseph Needham, in Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 3, ed. Joseph Needham (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1959), 614–617.

- Ibid., 615.

- Ibid., 611–612.

- Ibid., 609–610.

- Robert Temple, The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1986), 128–130.

Bibliography

- Aristotle. Meteorologica. Translated by H. D. P. Lee. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1952.

- Aristotle. Politics. Translated by Carnes Lord. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

- Landrum, Lisa. “Vitruvius and the Environment: Reconsidering Climate in Classical Architecture.” Journal of Architectural Historiography 27, no. 1 (2015): 31–48.

- Lehoux, Daryn. What Did the Romans Know?: An Inquiry into Science and Worldmaking. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- Shen Kuo. Dream Pool Essays (Mengxi Bitan). Translated by Joseph Needham. In Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 3. Edited by Joseph Needham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1959.

- Temple, Robert. The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1986.

- Vitruvius. Ten Books on Architecture. Translated by Ingrid D. Rowland and Thomas Noble Howe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.29.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.