Ancient healers laid the groundwork for systematic approaches to health and disease.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

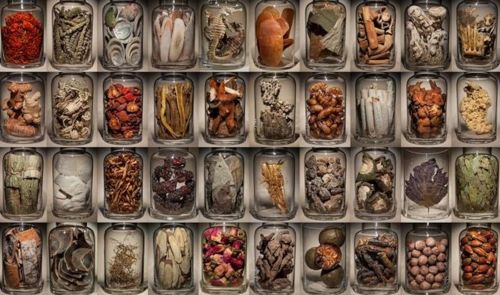

Herbal medicine, the practice of using plants for therapeutic purposes, represents one of the oldest and most widespread forms of healing known to humankind. In the ancient world, where spiritual belief, empirical observation, and rudimentary science intertwined, the use of herbs for medicinal purposes formed the foundation of medical practice across civilizations. From the organized pharmacopeias of Mesopotamia and Egypt to the elaborate treatises of Greco-Roman scholars and the holistic traditions of ancient China and India, herbal medicine was both a pragmatic response to illness and a reflection of a culture’s worldview. This essay explores the development, transmission, and cultural significance of herbal medicine in the ancient world, highlighting major civilizations and their contributions to the enduring legacy of phytotherapy.

Before the Written Word: Unearthing the Prehistoric Roots of Herbal Medicine

The use of herbs for healing in the prehistoric world long predates written history and reflects humankind’s earliest attempts to understand and manipulate the natural environment for survival. Anthropological and archaeological evidence suggests that early hominins may have possessed an instinctive awareness of the medicinal properties of certain plants. Observations of modern primates, such as chimpanzees self-medicating with particular leaves to expel parasites, support the hypothesis that early humans learned through observation and mimicry of animal behavior.1 This proto-pharmacological knowledge likely formed the basis for rudimentary herbal medicine, passed down orally across generations and integrated into the spiritual and social fabric of early hunter-gatherer communities.

The archaeological record provides striking examples of early herbal use, dating as far back as the Upper Paleolithic period. Excavations at Shanidar Cave in modern-day Iraq uncovered the remains of a Neanderthal burial site, dating to approximately 60,000 years ago, that contained traces of pollen from several medicinal plants, including yarrow (Achillea millefolium) and ephedra (Ephedra sinica).2 While the interpretation of this evidence remains contested—some argue it may have been introduced by burrowing animals—the concentration and variety of the pollen suggest intentional placement, possibly for ritual or medicinal purposes.3 If correct, this would mark one of the earliest known examples of phytotherapeutic knowledge in hominin history.

As humans transitioned from nomadic lifestyles to settled agricultural societies during the Neolithic Revolution (c. 10,000 BCE), their interaction with the plant world intensified. The domestication of both crops and medicinal herbs allowed for greater control over therapeutic resources and led to more sustained experimentation.4 Archaeobotanical finds from Neolithic sites across Europe, the Near East, and South Asia show that herbs such as poppy (Papaver somniferum), flax (Linum usitatissimum), and garlic (Allium sativum) were already in use, possibly for their analgesic, antiseptic, and nutritional properties.5 This period marks the genesis of more complex ethnobotanical traditions, wherein healing practices were increasingly formalized and intertwined with emerging religious and social hierarchies.

The spiritual dimensions of early herbal medicine cannot be understated. For many prehistoric societies, illness was not solely a biological phenomenon but also a metaphysical disturbance, requiring the intervention of shamans or ritual specialists. These figures combined empirical plant knowledge with trance, incantation, and symbolic gesture to heal the sick, often attributing the success of herbal remedies to divine or ancestral spirits.6 The dual belief in physical and spiritual causation helped cement the role of herbalists and shamans as crucial intermediaries between the human and the natural (or supernatural) world. This worldview persisted in later civilizations and influenced the syncretic development of medicine in cultures such as ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Mesoamerica.

Despite the lack of written records from prehistory, the enduring presence of specific plants in later pharmacological texts suggests a continuity of herbal knowledge across millennia. Ethnobotanical studies have shown that numerous herbs used by contemporary indigenous communities have roots in prehistoric use, preserved through oral tradition and communal memory.7 The long arc of herbal medicine’s development in the prehistoric world reveals a profound human desire to harness nature for healing—a desire that shaped the trajectory of ancient medical systems and continues to inform modern alternative therapies. By piecing together archaeological data, comparative ethnographies, and evolutionary biology, scholars can begin to reconstruct the foundational stages of one of humanity’s most ancient sciences.

Elixirs of the Euphrates: Herbal Healing in Ancient Mesopotamia

The cradle of civilization, ancient Mesopotamia, saw some of the earliest recorded developments in medicine, particularly herbal healing. Situated between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Mesopotamian societies—especially the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians—crafted a complex medical tradition that merged empirical observation with spiritual belief. Cuneiform tablets dating to the third millennium BCE reveal that Mesopotamian healers used a wide array of plants for treating diseases, including licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra), thyme (Thymus vulgaris), and juniper (Juniperus communis).8 These remedies were often combined with prayers, rituals, and incantations, illustrating the dualistic Mesopotamian view of illness as both physical and supernatural in origin.

The practitioners of medicine in Mesopotamia were divided into distinct roles: the āšipu, or exorcist-priest, and the asû, or physician. The āšipu primarily addressed spiritual causes of disease through ritual and magic, while the asû engaged in empirical treatment, frequently utilizing herbs and other natural substances.9 The collaboration between these two roles underscores a sophisticated understanding of illness that recognized both psychological and physical dimensions. Many therapeutic texts, such as those found in the Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh, contain extensive herbal formularies that suggest systematic experimentation and the development of materia medica. Tablets often provided instructions on how to prepare and administer remedies—whether as infusions, poultices, or salves.10

Mesopotamian herbal medicine was deeply embedded in religious and cosmological belief systems. Illness was frequently attributed to divine wrath, sin, or malevolent spirits. Consequently, medical texts were replete with prayers to gods such as Ea (the god of wisdom and magic) and Gula (the goddess of healing), who were invoked to sanctify and potentiate herbal treatments.11 Ritual purity was crucial to the preparation and administration of herbal concoctions, often requiring ceremonial cleansing or the utterance of sacred words. This fusion of pharmacology and spirituality provided psychological reassurance for the patient while reinforcing the social authority of the healer.

The Mesopotamians also demonstrated a remarkable degree of botanical knowledge and experimentation. Over 250 plant substances are identified in surviving texts, including opium poppy, myrrh, mandrake, henbane, and various resins and barks.12 These materials were imported from distant regions as part of a larger trade in exotic medicinal goods, underscoring the cosmopolitan nature of Mesopotamian medicine. Moreover, their use suggests a detailed awareness of plant morphology and efficacy. For example, licorice was used to soothe coughs and treat inflammation—uses consistent with its pharmacological properties confirmed by modern science.13 Such examples reveal that Mesopotamian herbalism was not merely mystical, but often based on keen empirical observation.

Though the medical theories of ancient Mesopotamia were eventually overshadowed by Greco-Roman traditions, their foundational contributions endured. Babylonian and Assyrian texts influenced later medical compendia in the Hellenistic and Islamic worlds, especially through their preservation and transmission via the libraries of Persia and the Near East.14 The herbal legacy of Mesopotamia illustrates the enduring human quest to understand and manipulate the natural world for healing. It represents one of the earliest chapters in the global history of medicine, where empirical insight and sacred tradition coalesced to forge a system of healing that would resonate through millennia.

Nile Remedies: Unveiling the Herbal Healing Traditions of Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt stands as one of the most influential cradles of early medicine, where herbal practices were deeply interwoven with religion, ritual, and empirical healing. The Egyptian worldview considered health a state of harmony among the body, the spirit (ka), and the cosmic order (ma’at). Illness, accordingly, was seen as a disruption of this balance, and healing involved restoring that equilibrium through various means, including the administration of medicinal plants. Egyptian physicians—some of the earliest known by name, such as Imhotep—were highly respected professionals who drew upon extensive formularies of herbs to treat a wide range of ailments.15 These practices were not merely instinctive or mystical; they were codified in medical papyri that represent some of the oldest extant medical texts in human history.

Among the most important of these documents is the Ebers Papyrus, dating to around 1550 BCE, which contains over 700 remedies and prescriptions, many of which center on herbal treatments. It details the use of plants such as garlic (Allium sativum) for cardiovascular health, aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis) for skin conditions, and willow bark (Salix spp.) for inflammation and pain—an early use of what would later be identified as salicylic acid, the precursor to aspirin.16 The Edwin Smith Papyrus, though focused more on surgical practices, also references herbal applications for wound care. These texts illustrate a high degree of specialization, where herbal knowledge was not isolated but integrated with anatomy, prognosis, and procedure.17 Notably, these remedies were prepared in specific forms such as poultices, tinctures, pills, and suppositories, indicating a sophisticated understanding of pharmacological delivery.

Religious belief and magical practice were also integral to Egyptian medicine. Herbs were not only physical treatments but sacred substances imbued with divine power. Healing rituals often invoked deities such as Sekhmet, the goddess of plague and healing; Isis, associated with maternal care and magic; and Thoth, god of knowledge and medicine.18 Many herbal prescriptions were recited with incantations or accompanied by amulets, underscoring the belief that spiritual and physical treatment were inseparable. For example, a concoction made with frankincense (Boswellia sacra) or myrrh (Commiphora myrrha) might be used to purify both the body and soul. This spiritual dimension elevated the physician to a priestly role and cast the act of healing as a moral and cosmological duty.

The Nile River and its surrounding ecology provided a rich botanical landscape that sustained Egypt’s herbal tradition. The annual flooding deposited nutrient-rich silt that fostered the growth of native medicinal plants, while Egypt’s extensive trade networks brought exotic substances from as far as Nubia, the Levant, and even India.19 Papyrus reeds, fenugreek, coriander, castor, and senna were among the plants commonly used. The Egyptian pharmacopoeia was remarkable not only in its diversity but in its empirical refinement; herbs were often tested and combined in ways that reveal an experimental, proto-scientific approach. This knowledge was carefully guarded and transmitted through temple schools, especially in centers like Heliopolis and Per-Bast, where priest-physicians were trained in the arts of diagnosis and healing.

The legacy of Egyptian herbal medicine extended far beyond the banks of the Nile. As Greek and Roman scholars visited and studied Egyptian temples and libraries, they absorbed this medical wisdom into their own systems. Notably, Hippocrates, Galen, and Dioscorides all referenced Egyptian practices and remedies in their works.20 Through the translation of Egyptian medical texts into Greek, Coptic, and eventually Arabic, the ancient herbal tradition continued to influence Islamic medicine and, later, medieval European practices. The enduring relevance of Egyptian plant medicine—even echoed in modern naturopathy—speaks to its foundational place in the global history of healing. It is a testament to the ingenuity of early human attempts to understand the body and harness nature’s remedies.

Healing Herbs of Antiquity: The Greco-Roman Legacy of Herbal Medicine

Greco-Roman herbal medicine represents a critical juncture in the history of healing, where natural philosophy, empirical observation, and inherited traditions from earlier civilizations converged into a more formalized medical system. The Greeks inherited much from Egyptian and Mesopotamian practices but developed a distinct theoretical framework based on humoral theory. This paradigm, attributed to Hippocrates and later systematized by Galen, posited that health depended on the balance of four bodily humors—blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile—and that herbal remedies could help restore this balance.21 For example, herbs with heating or cooling properties were used to counteract excesses of cold or hot humors. Plants thus became categorized not only by their physiological effects but also by their “temperaments”—a classification that would shape pharmacology for centuries.

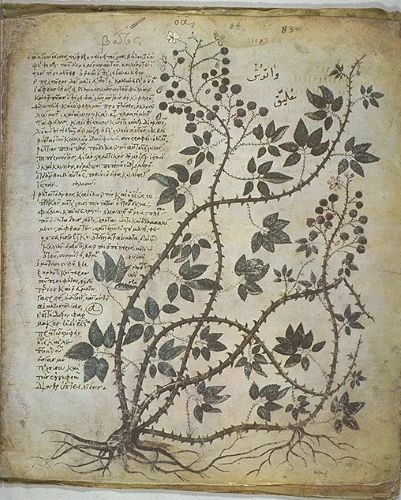

Hippocrates (c. 460–370 BCE), often called the “Father of Medicine,” laid the groundwork for Greek medical ethics and clinical observation. Though his surviving corpus mentions a limited number of herbs, he emphasized dietary and botanical remedies over magical or supernatural ones.22 It was, however, the physician Dioscorides in the 1st century CE who produced the most influential pharmacological text of antiquity: the De Materia Medica. This five-volume compendium described over 600 plants, along with their uses, preparations, and effects.23 Dioscorides traveled extensively as a military physician in the Roman Empire, and his observations were practical, organized, and enduring; his work remained a standard reference in both the Islamic world and medieval Europe for over 1,500 years.

Galen of Pergamon (129–c. 216 CE), a towering figure in Roman medicine, expanded on Hippocratic and Dioscoridean traditions by synthesizing theory with clinical application. He codified the four-humor system and used herbal medicines extensively to modify bodily imbalances.24 Galen emphasized compound remedies—often complex mixtures of multiple herbs and minerals—which he believed acted synergistically. His development of theriaca, an elaborate antidote composed of dozens of ingredients, including opium, myrrh, and cinnamon, epitomizes the Greco-Roman fascination with panaceas. These formulations were popularized in Roman apothecaries and continued to influence medical practice in Byzantine and Islamic contexts.

Greco-Roman medicine also benefited from the Roman Empire’s vast botanical diversity and trade networks, which allowed access to plants from regions as far-flung as India, Egypt, Gaul, and North Africa. The Romans cultivated numerous medicinal herbs in household gardens and formal horti medici (medical gardens), such as those overseen by Roman military camps or temple complexes.25 Commonly used herbs included fennel, sage, rosemary, thyme, mint, and valerian, as well as imported substances like cinnamon, ginger, and frankincense. Roman authors such as Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, compiled encyclopedic knowledge about plants, blending medicinal uses with folklore and anecdotal evidence.26 While less systematically rigorous than Dioscorides, Pliny’s work reflects the Greco-Roman desire to document and organize natural knowledge.

The legacy of Greco-Roman herbal medicine is vast and enduring. Medical texts by Dioscorides and Galen were translated into Arabic, Latin, and Syriac, forming the backbone of medical curricula in the Islamic Golden Age and the European Middle Ages. These herbal traditions laid the groundwork for Renaissance botany and the emergence of pharmacognosy in the modern period.27 The Greco-Roman approach to medicine, blending rational theory with practical herbalism, created a template for integrating empirical observation with systematic classification. Even today, many herbal remedies in Western alternative medicine—such as chamomile for sleep or peppermint for digestion—can trace their origins back to the prescriptions of Hippocratic and Galenic medicine.

Timeless Healing: The Living Traditions of Ayurveda and Chinese Herbal Medicin

Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) are two of the world’s oldest and most comprehensive systems of herbal medicine, each with unique philosophies and methods that have evolved over millennia. Ayurveda, meaning “science of life,” originated in the Indian subcontinent around 1500 BCE with roots in the Vedic tradition. It is grounded in the belief that health arises from the balance of three vital energies or doshas: Vata (air and ether), Pitta (fire and water), and Kapha (earth and water). Herbal medicine in Ayurveda aims to restore harmony among these doshas through personalized treatments that include plant-based formulations, diet, and lifestyle changes.28 The Charaka Samhita and Sushruta Samhita, two foundational Ayurvedic texts, describe hundreds of medicinal plants and their therapeutic applications, ranging from turmeric (Curcuma longa) for inflammation to neem (Azadirachta indica) for infections.29

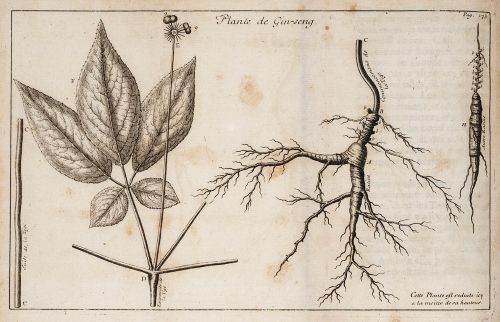

Similarly, Traditional Chinese Medicine traces its origins back over 2,000 years, drawing on an extensive philosophical framework based on Qi (vital energy), Yin and Yang balance, and the Five Elements (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water). TCM herbalism employs complex prescriptions, combining multiple herbs to correct internal imbalances and restore the flow of Qi through the body’s meridians. Classic texts like the Shennong Bencao Jing (Divine Farmer’s Materia Medica) catalog hundreds of medicinal substances, including ginseng (Panax ginseng), licorice (Glycyrrhiza uralensis), and astragalus (Astragalus membranaceus), which are still widely used today.30 TCM practitioners assess symptoms in the context of systemic disharmony, using herbal formulas tailored to individual constitution and condition, reflecting a highly holistic approach.

Both systems emphasize the importance of individualized treatment and preventative care, but they differ in their conceptualizations of disease and treatment strategies. Ayurveda integrates spiritual, physical, and psychological elements, emphasizing detoxification (panchakarma), rejuvenation (rasayana), and diet as therapeutic pillars. Herbal remedies are often prepared as powders, oils, decoctions, or pastes, and they play a central role in daily life and rituals.31 Conversely, TCM’s focus is on restoring balance within a dynamic system through harmonizing Yin and Yang and unblocking Qi. TCM herbs are combined in specific ratios to enhance efficacy and reduce side effects, reflecting an intricate knowledge of herb-herb interactions. This complex formulation practice demonstrates an empirical understanding of pharmacodynamics long before modern pharmacology.32

The transmission and preservation of Ayurvedic and Chinese herbal knowledge were deeply embedded in cultural, religious, and scholarly traditions. In India, Ayurveda was transmitted orally and through manuscripts, with physicians known as vaidyas often belonging to family lineages. The practice was closely linked to Hinduism and later incorporated Buddhist influences.33 In China, TCM was institutionalized through imperial medical colleges and classical texts, with herbal medicine being a fundamental component alongside acupuncture and massage. Both traditions faced periods of suppression and revival, especially during the colonial era and modernization efforts but have experienced significant global resurgence since the 20th century. Today, both Ayurveda and TCM are recognized by the World Health Organization as valuable complementary medical systems.34

Modern research has begun to validate many herbal remedies from Ayurveda and TCM, uncovering bioactive compounds that support traditional uses. Curcumin from turmeric exhibits anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties consistent with Ayurvedic claims, while ginsenosides in ginseng have been shown to modulate immune responses, echoing TCM’s emphasis on vitality.35 Despite this, challenges remain in standardizing herbal preparations and ensuring safety, as both systems rely on complex mixtures rather than isolated compounds. Nonetheless, Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine continue to inspire integrative approaches in global health, offering ancient wisdom alongside modern science in the ongoing quest for holistic well-being.

Sacred Remedies: Herbal Medicine and Healing Traditions of Ancient Mesoamerica

Ancient Mesoamerican civilizations, including the Maya, Aztec, and Olmec, developed rich and complex traditions of herbal medicine and healing deeply intertwined with their religious and cosmological beliefs. These cultures viewed health as a dynamic balance between the physical body, spiritual forces, and the natural world. Herbal remedies were not merely pharmacological agents but were often imbued with symbolic significance, used in ritual contexts to invoke divine protection or to restore harmony with nature.36 The Aztecs, in particular, compiled extensive botanical knowledge, categorizing hundreds of plants by their perceived powers and applications. Their herbalists, known as ticitl, combined botanical expertise with ritual practices, using plants to treat a wide array of ailments from fevers to spiritual maladies.

The codices and post-Conquest manuscripts, such as the Florentine Codex compiled by Bernardino de Sahagún in the 16th century, provide crucial insight into Mesoamerican herbal medicine. This work documents the use of more than 300 medicinal plants by the Aztecs, illustrating their methods of preparation—ranging from infusions and poultices to smoke inhalations—and their therapeutic purposes. For example, the Aztecs used peyotl (peyote cactus) for its psychoactive properties in healing ceremonies and cuetlaxochitl (the Mexican marigold) for treating wounds and inflammation.37 This blend of botanical knowledge with ritual efficacy illustrates how healing was as much about restoring spiritual equilibrium as physical health.

Maya herbal medicine was similarly sophisticated and integrated with spiritual beliefs. The Maya considered the jungle a living pharmacy, with shamans and healers, called ah-men or ajq’ij, employing a wide range of native plants for medicinal, magical, and divinatory purposes. Archaeological evidence from sites such as Copán reveals botanical remains suggesting the use of plants like chicatana ants and cacao, both for nutrition and therapeutic effects. Maya texts such as the Ritual of the Bacabs describe herbal treatments aimed at balancing bodily humors, alleviating pain, and protecting against malevolent spirits.38 The knowledge was passed down orally and through ritual instruction, emphasizing the interdependence of physical and spiritual health.

The Mesoamerican approach to herbal medicine was holistic and preventative as well as curative. Many plants were incorporated into daily diet or personal hygiene routines to maintain wellness and ward off illness. For instance, the Aztecs valued amaranth not only as a nutritious food but also for its medicinal properties in strengthening the body.39 Likewise, herbal baths, steam treatments, and fumigations with fragrant plants were common practices to cleanse and protect the body. These treatments reflect a deep understanding of the healing environment and its connection to social and cosmic order, demonstrating that health was inseparable from community and spirituality.

Despite the catastrophic disruptions caused by European colonization, many Mesoamerican herbal traditions have persisted and continue to influence modern herbalism in Mexico and Central America. Contemporary indigenous healers still use many plants documented in ancient codices, preserving their medicinal and ritual significance. Recent ethnobotanical research confirms the pharmacological efficacy of several traditional remedies, such as hierba del cancer (Cestrum nocturnum) and chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla), which validate centuries-old indigenous wisdom.40 Thus, ancient Mesoamerican herbal medicine represents not only a historical legacy but a living tradition that continues to enrich global knowledge of natural healing.

The Rich Legacy of Native American Herbal Medicine and Healing

Native American herbal medicine represents one of the most diverse and sophisticated bodies of traditional botanical knowledge in the world, deeply rooted in a spiritual understanding of nature and health. Indigenous peoples across North America developed distinct healing traditions that reflected their unique environments and cultural values. For Native communities, plants were not simply remedies but were considered gifts from the Creator, possessing both physical and spiritual healing powers. The role of the healer, often called a medicine person or shaman, was to mediate between the natural and spiritual worlds, using herbs in combination with ritual, prayer, and ceremonies to restore balance and well-being.41

The Cherokee, one of the most studied tribes for their herbal knowledge, utilized a wide variety of native plants such as Echinacea (purple coneflower) to boost immunity and treat infections, and black cohosh for women’s health. Their traditional pharmacopoeia also included yarrow for wound healing and willow bark as a natural pain reliever—an early form of aspirin.42 The Ojibwe, another prominent group, employed sweetgrass in purification rituals and used wild ginger and cedar for respiratory ailments. These plants were gathered and prepared with great respect, and knowledge was transmitted orally through generations, often in secret to preserve the sacredness of the practice.43

Healing in Native American culture was holistic, integrating mind, body, and spirit. Herbal treatments were often part of larger ceremonies designed to cleanse negative energies, foster community harmony, and connect with ancestral wisdom. Sweat lodges, vision quests, and healing dances accompanied the use of medicinal plants to amplify their curative effects.44 The Navajo, for instance, combined herbal remedies like yucca and sage with chants and sand paintings to heal physical and spiritual ailments. This integrative approach underscores the profound interconnectedness between people, land, and medicine that defines indigenous healing traditions.

The arrival of European settlers brought devastating disruptions to Native American herbal medicine through forced relocation, loss of habitat, and cultural suppression. Many plants crucial to indigenous pharmacopeias were displaced or overharvested, while traditional knowledge faced marginalization. Nevertheless, Native communities adapted and preserved much of their herbal wisdom, sometimes integrating European remedies without losing the core spiritual practices. In recent decades, there has been a resurgence of interest in Native herbal medicine both within indigenous communities and the wider world, emphasizing cultural revival and ecological stewardship.45

Contemporary research increasingly acknowledges the value of Native American herbal medicine. Scientific studies have confirmed the pharmacological properties of several traditional herbs, such as Echinacea’s immune-stimulating effects and willow bark’s analgesic compounds.46 Beyond the biochemical, Native healing practices emphasize sustainability, respect for biodiversity, and the sacredness of life, offering vital insights into holistic health. Today, Native American herbal medicine continues to be a living tradition, practiced by healers and honored as a vital part of cultural identity and resilience.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

Though the rise of modern pharmacology in the 19th and 20th centuries shifted focus to synthetic drugs and laboratory-based medicine, the legacy of ancient herbalism persists. Many modern pharmaceuticals are derived from compounds originally discovered in herbs used by ancient civilizations. For example, morphine derives from the opium poppy, and aspirin from willow bark—both with deep historical roots.

Contemporary interest in integrative and holistic medicine has led to renewed respect for traditional herbal practices, including Ayurveda and TCM. Archaeological discoveries continue to illuminate ancient medical practices, and interdisciplinary studies combining history, botany, and pharmacology offer insights into the efficacy and cultural context of historical remedies.

Conclusion

Herbal medicine in the ancient world was far more than a primitive forerunner to modern pharmacology—it was a rich, dynamic tradition informed by observation, spirituality, trial and error, and cultural exchange. Ancient healers laid the groundwork for systematic approaches to health and disease, many of which resonate in contemporary alternative and complementary medicine. As we continue to explore ancient texts and reevaluate natural remedies, the wisdom of past civilizations may yet offer valuable contributions to future healthcare.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Michael A. Huffman, “Animal Self-Medication and Ethnobotany: Exploration and Exploitation of the Medicinal Properties of Plants,” Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 62, no. 2 (2003): 371–381.

- Ralph S. Solecki, “Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal Flower Burial in Northern Iraq,” Science 190, no. 4217 (1975): 880–881.

- Jeffrey D. Sommer, “The Shanidar IV ‘Flower Burial’: A Reevaluation of Neanderthal Burial Ritual,” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 9, no. 1 (1999): 127–129.

- Deborah M. Pearsall, Paleoethnobotany: A Handbook of Procedures, 2nd ed. (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2008).

- Daniel Zohary, Maria Hopf, and Ehud Weiss, Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin, 4th ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

- Mircea Eliade, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, trans. Willard R. Trask (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1964).

- William Balée, Footprints of the Forest: Ka’apor Ethnobotany—The Historical Ecology of Plant Utilization by an Amazonian People (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994).

- Marten Stol, Women in the Ancient Near East (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016), 232.

- JoAnn Scurlock and Burton R. Andersen, Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005), 35–37.

- Irving L. Finkel, “On the Rules for the Preparation of Medicines in Ancient Mesopotamia,” Pharmaceutical Historian 28, no. 1 (1998): 3–6.

- Jean Bottéro, Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia, trans. Teresa Lavender Fagan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 146–148.

- Annette Imhausen and Tanja Pommerening, eds., Writings of Early Scholars in the Ancient Near East, Egypt, Rome, and Greece: Translating Ancient Scientific Texts (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2010), 59.

- John F. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996), 95.

- P. W. Singer, The Legacy of Mesopotamian Medicine (London: Routledge, 2003), 118–120.

- Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 11-13.

- Paul Ghalioungui, Magic and Medical Science in Ancient Egypt (New York: B. Franklin, 1963), 73–75.

- James P. Allen, The Art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005), 28–30.

- Rosalie David, Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt (London: Penguin Books, 2002), 97–99.

- Lisa Manniche, An Ancient Egyptian Herbal (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989), 14–16.

- Vivian Nutton, Ancient Medicine (London: Routledge, 2004), 97–100.

- Nutton, Ancient Medicine, 130-133.

- Wesley D. Smith, Hippocrates: Pseudepigraphic Writings (Leiden: Brill, 1990), 45–47.

- Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, trans. Lily Y. Beck (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005), xii–xvi.

- Owsei Temkin, Galenism: Rise and Decline of a Medical Philosophy (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1973), 55–58.

- Heinrich von Staden, “Botanical Medicine in the Roman World,” in Hortus Romanus: Gardens and Gardening in the Ancient World, ed. J. Wilkins (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2010), 92–95.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History, trans. H. Rackham (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1938), Book 20.

- John M. Riddle, Dioscorides on Pharmacy and Medicine (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985), 199–203.

- Dominik Wujastyk, The Roots of Ayurveda (New Delhi: Penguin Books India, 2003), 15–18.

- P.V. Sharma, Charaka Samhita (Varanasi: Chaukhambha Sanskrit Series, 1994), 42–45.

- B.J. Fruehauf, The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine: A New Translation of the Neijing Suwen with Commentary (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 75–78.

- C.P. Khare, Indian Herbal Remedies: Rational Western Therapy, Ayurvedic and Other Traditional Usage, Botany (Springer, 2007), 203–205.

- Giovanni Maciocia, The Foundations of Chinese Medicine: A Comprehensive Text (Churchill Livingstone, 1989), 118–121.

- Paul U. Unschuld, Medicine in China: A History of Ideas (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 93–95.

- World Health Organization, Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014–2023 (Geneva: WHO Press, 2013), 14–15.

- Aggarwal, Bharat B., and Prashasnika K. Harikumar. “Potential Therapeutic Effects of Curcumin, the Anti-Inflammatory Agent, Against Neurodegenerative, Cardiovascular, Pulmonary, Metabolic, Autoimmune and Neoplastic Diseases.” International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 41, no. 1 (2009): 40–59.

- H. B. Nicholson, “Aztec Herbal Medicine and Its Cultural Context,” Journal of Ethnobiology 12, no. 2 (1992): 145–147.

- Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, trans. Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble (Santa Fe: School of American Research, 1950–1982), Book 11, 210–220.

- Matthew G. Looper, “The Ritual of the Bacabs and Maya Healing Traditions,” Ancient Mesoamerica 23, no. 1 (2012): 77–80.

- Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, “Amaranth and the Aztec Herbal Tradition,” in Plants and Power: Ancient Links, ed. J. Hendon and B. N. Nelson (Los Angeles: UCLA Press, 1999), 135–138.

- Blanca León, et al., “Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in Oaxaca, Mexico,” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 120, no. 2 (2008): 331–337.

- Michael J. Balick and Paul Alan Cox, Plants, People, and Culture: The Science of Ethnobotany (New York: Scientific American Library, 1996), 112–114.

- Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland: Timber Press, 1998), 145–148.

- Frances Densmore, Chippewa Music (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1919), 232–235.

- Gary Witherspoon, “Healing Ceremonies and Herbal Medicine Among the Navajo,” American Indian Quarterly 12, no. 3 (1988): 205–210.

- Linda Black Elk and Rosemarie Dunbar-Ortiz, Native American Medicine and Healing (New York: Rosen Publishing, 2008), 70–72.

- Barbara S. Weeks, “Pharmacological Properties of Medicinal Plants Used by Native Americans,” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 35, no. 2 (1991): 123–130.

Bibliography

- Aggarwal, Bharat B., and Prashasnika K. Harikumar. “Potential Therapeutic Effects of Curcumin, the Anti-Inflammatory Agent, Against Neurodegenerative, Cardiovascular, Pulmonary, Metabolic, Autoimmune and Neoplastic Diseases.” International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 41, no. 1 (2009): 40–59.

- Allen, James P. The Art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.

- Balée, William. Footprints of the Forest: Ka’apor Ethnobotany—The Historical Ecology of Plant Utilization by an Amazonian People. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

- Balick, Michael J., and Paul Alan Cox. Plants, People, and Culture: The Science of Ethnobotany. New York: Scientific American Library, 1996.

- Black Elk, Linda, and Rosemarie Dunbar-Ortiz. Native American Medicine and Healing. New York: Rosen Publishing, 2008.

- Bottéro, Jean. Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia. Translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- David, Rosalie. Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt. London: Penguin Books, 2002.

- Densmore, Frances. Chippewa Music. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1919.

- Dioscorides. De Materia Medica. Translated by Lily Y. Beck. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005.

- Eliade, Mircea. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Translated by Willard R. Trask. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1964.

- Finkel, Irving L. “On the Rules for the Preparation of Medicines in Ancient Mesopotamia.” Pharmaceutical Historian 28, no. 1 (1998): 3–6.

- Fruehauf, B.J. The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine: A New Translation of the Neijing Suwen with Commentary. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

- Ghalioungui, Paul. Magic and Medical Science in Ancient Egypt. New York: B. Franklin, 1963.

- Huffman, Michael A. “Animal Self-Medication and Ethnobotany: Exploration and Exploitation of the Medicinal Properties of Plants.” Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 62, no. 2 (2003): 371–381.

- Imhausen, Annette, and Tanja Pommerening, eds. Writings of Early Scholars in the Ancient Near East, Egypt, Rome, and Greece: Translating Ancient Scientific Texts. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2010.

- Khare, C.P. Indian Herbal Remedies: Rational Western Therapy, Ayurvedic and Other Traditional Usage, Botany. Springer, 2007.

- León, Blanca, et al. “Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in Oaxaca, Mexico.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 120, no. 2 (2008): 331–337.

- Looper, Matthew G. “The Ritual of the Bacabs and Maya Healing Traditions.” Ancient Mesoamerica 23, no. 1 (2012): 77–80.

- Maciocia, Giovanni. The Foundations of Chinese Medicine: A Comprehensive Text. Churchill Livingstone, 1989.

- Manniche, Lisa. An Ancient Egyptian Herbal. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo. “Amaranth and the Aztec Herbal Tradition.” In Plants and Power: Ancient Links, edited by J. Hendon and B. N. Nelson, 135–138. Los Angeles: UCLA Press, 1999.

- Moerman, Daniel E. Native American Ethnobotany. Portland: Timber Press, 1998.

- Nicholson, H. B. “Aztec Herbal Medicine and Its Cultural Context.” Journal of Ethnobiology 12, no. 2 (1992): 145–147.

- Nunn, John F. Ancient Egyptian Medicine. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996.

- Nutton, Vivian. Ancient Medicine. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Pearsall, Deborah M. Paleoethnobotany: A Handbook of Procedures. 2nd ed. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2008.

- Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Translated by H. Rackham. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1938.

- Riddle, John M. Dioscorides on Pharmacy and Medicine. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985.

- Sahagún, Bernardino de. Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain. Translated by Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble. Santa Fe: School of American Research, 1950–1982.

- Scurlock, JoAnn, and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005.

- Sharma, P.V. Charaka Samhita. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Sanskrit Series, 1994.

- Singer, P. W. The Legacy of Mesopotamian Medicine. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Smith, Wesley D. Hippocrates: Pseudepigraphic Writings. Leiden: Brill, 1990.

- Solecki, Ralph S. “Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal Flower Burial in Northern Iraq.” Science 190, no. 4217 (1975): 880–881.

- Sommer, Jeffrey D. “The Shanidar IV ‘Flower Burial’: A Reevaluation of Neanderthal Burial Ritual.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 9, no. 1 (1999): 127–129.

- Stol, Marten. Women in the Ancient Near East. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016.

- Temkin, Owsei. Galenism: Rise and Decline of a Medical Philosophy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1973.

- Unschuld, Paul U. Medicine in China: A History of Ideas. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

- von Staden, Heinrich. “Botanical Medicine in the Roman World.” In Hortus Romanus: Gardens and Gardening in the Ancient World, edited by J. Wilkins, 85–105. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2010.

- Weeks, Barbara S. “Pharmacological Properties of Medicinal Plants Used by Native Americans.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 35, no. 2 (1991): 123–130.

- Witherspoon, Gary. “Healing Ceremonies and Herbal Medicine Among the Navajo.” American Indian Quarterly 12, no. 3 (1988): 205–210.

- Wujastyk, Dominik. The Roots of Ayurveda. New Delhi: Penguin Books India, 2003.

- World Health Organization. Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014–2023. Geneva: WHO Press, 2013.

- Zohary, Daniel, Maria Hopf, and Ehud Weiss. Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.30.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.