No evidence has been found for a large-scale migration of Israelites from Egypt.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The Exodus story stands as one of the most dramatic and influential narratives in the Hebrew Bible. According to the Book of Exodus, a large population of Israelite slaves escaped from Egypt under the leadership of Moses, wandered in the desert for forty years, and eventually conquered Canaan, the land promised to them by their God. For centuries, this account was taken as historical fact by Jews, Christians, and Muslims alike. However, over the past century, advances in archaeology, Egyptology, and biblical scholarship have challenged the historicity of the Exodus narrative. Despite exhaustive efforts, scholars have found no archaeological or historical evidence that convincingly supports the biblical account. Here I examine the lack of evidence for the Exodus from archaeological, historical, and textual standpoints, and explores alternative theories that explain the origins of the narrative.

The Biblical Account of the Exodus

The Exodus has traditionally been dated to somewhere between the 15th and 13th centuries BCE, depending on the interpretation of biblical chronologies and synchronisms with Egyptian history. The most commonly suggested dates are around 1450 BCE (based on 1 Kings 6:1, which states the Exodus happened 480 years before the construction of Solomon’s Temple) or around 1250 BCE (based on archaeological interpretations and references to the construction of the city of Pi-Ramesses).

The Exodus narrative, found primarily in the second book of the Hebrew Bible, is one of the most defining stories in Jewish tradition and a central motif in Christian theology. It begins with the Israelites’ enslavement in Egypt, where they are subjected to harsh labor under a Pharaoh who fears their growing numbers. The figure of Moses emerges as the divinely appointed leader who, after a dramatic personal calling at the burning bush, becomes the intermediary between God and Pharaoh. Through Moses, Yahweh delivers ten devastating plagues upon Egypt, each designed to demonstrate divine supremacy over Egyptian deities and to compel Pharaoh to release the Israelites. The narrative climaxes in the miraculous parting of the Red Sea, where the Israelites escape and the Egyptian army perishes. The text presents these events not merely as historical but as theological truths, highlighting divine intervention, judgment, and deliverance.1

Following their departure, the Israelites embark on a forty-year journey through the wilderness, guided by a pillar of cloud by day and fire by night. This period of wandering is framed as a time of testing, purification, and covenantal reaffirmation. At Mount Sinai, the Israelites receive the Law, including the Ten Commandments, which serve as the foundation for Israelite religious and ethical life. The narrative thus shifts from liberation to legislation, emphasizing the establishment of a people set apart by divine law. God’s presence is manifest not only through dramatic events but also in the meticulous instructions for constructing the Tabernacle, a mobile sanctuary symbolizing God’s dwelling among His people. This legal and liturgical structure reinforces the identity of the Israelites as a chosen people in covenantal relationship with Yahweh.2

The Exodus story also includes detailed genealogies, census data, and descriptions of tribal arrangements, giving the impression of a well-organized nomadic population. These details, however, are often at odds with what is known from archaeology and ancient Near Eastern history. The text claims that over 600,000 men, not counting women and children, left Egypt—a figure which would suggest a migrating population of over two million people.3 Such numbers would have had a massive demographic and ecological impact, yet no corresponding evidence has been found in the Sinai Peninsula or surrounding regions. While these figures may reflect theological symbolism rather than historical reality, they serve within the narrative to emphasize the scale of divine deliverance and the birth of a nation from bondage.

Embedded within the Exodus narrative are theological themes that have resonated through millennia. Chief among them is the motif of liberation: God hears the cries of the oppressed and acts decisively to free them. The story is not merely about escape from physical bondage but about transformation into a people bound by divine law and purpose. The language of covenant, promise, and divine fidelity ties the Exodus to earlier promises made to the patriarchs—Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—and projects forward to the conquest and settlement of Canaan. This theological arc provides a foundational myth that explains not only the origins of the Israelite nation but also its ethical obligations and special status among the nations.4

In its final chapters, the book of Exodus transitions into more priestly concerns, outlining the construction of the Tabernacle and the institution of religious rituals. These passages, often seen as tedious by modern readers, were central to ancient Israelite religion and identity. They reflect a shift from narrative to instruction, indicating that the Exodus was not merely about deliverance but about the formation of a liturgical community. The instructions regarding the Ark of the Covenant, priestly garments, and sacrificial rituals underscore the sacred order that must be maintained in response to divine presence. In this way, the Exodus account serves multiple functions: it is a story of liberation, a charter for national identity, and a guide for religious practice. Its enduring power lies not in historical precision, but in its profound narrative and theological coherence.5

Lack of Archaeological Evidence

Despite the centrality of the Exodus story in the Hebrew Bible, archaeologists have not uncovered any direct evidence supporting the narrative’s historicity. For over a century, systematic excavations throughout Egypt, the Sinai Peninsula, and the southern Levant have failed to reveal material traces of a large-scale Israelite migration from Egypt. The biblical text describes hundreds of thousands of people journeying through the desert for forty years, constructing temporary camps and leaving behind a trail of movement and settlement. Yet surveys conducted by archaeologists such as Israel Finkelstein and others have turned up no signs—no pottery shards, no burial grounds, no shelters, and no refuse deposits—indicative of such a vast population living nomadically in the wilderness.6 This absence of evidence has led many scholars to conclude that if an Exodus occurred, it did not happen on the scale or in the manner described in the Bible.

Compounding the issue is the lack of mention in Egyptian sources. The Egyptians, known for their prolific and detailed record-keeping, never recorded an event resembling the Exodus—no indication of a massive slave population fleeing, no economic disruption, and no defeat of the Egyptian army by natural or supernatural forces. Documents from the New Kingdom period, especially during the reigns of Seti I and Ramesses II (commonly associated with the Exodus story by some scholars), are silent on such matters. While it is conceivable that a humiliating loss might be omitted from royal inscriptions, Egypt’s administrative papyri and bureaucratic records are also devoid of such a reference. Kenneth Kitchen, a conservative scholar often defending the general reliability of biblical texts, acknowledges this absence but attempts to explain it as a consequence of Egyptian ideological biases, arguing that historical defeats were routinely omitted.7 Still, the magnitude of the Exodus described in the Bible makes its total absence from Egyptian sources a profound historical problem.

Equally problematic is the biblical claim that over 600,000 Israelite men—plus women and children—fled Egypt, which would indicate a population of at least two million people. Such a demographic shift would have required a logistical and ecological framework that seems implausible in the arid terrain of the Sinai. As William G. Dever notes, even allowing for hyperbolic biblical numbers, there is no archaeological footprint of a substantial transitory population in the wilderness, nor is there evidence of the infrastructure required to support it.8 Sites such as Kadesh-barnea, identified as a key Israelite encampment, show only limited occupation layers that do not support the claim of prolonged, large-scale habitation during the Late Bronze Age. Similarly, no evidence of sudden, widespread cultural or ethnic shifts exists in the Levantine archaeological record at the time traditionally associated with the conquest following the Exodus.

Furthermore, cities said to have been conquered by the Israelites shortly after the Exodus—such as Jericho, Ai, and Hazor—do not exhibit destruction layers corresponding with the biblical chronology. Excavations at Jericho, conducted by Kathleen Kenyon in the mid-twentieth century, revealed that the city had been largely uninhabited around the time the Exodus would have occurred, contradicting the biblical account of its walls miraculously falling after Joshua’s siege.9 Ai, another city said to have been utterly destroyed by the Israelites, was found to have been abandoned centuries before the alleged conquest. Only Hazor shows evidence of destruction, but the dating of this event is inconsistent and could relate to broader regional upheavals unrelated to any Israelite campaign.10 These archaeological findings suggest that the biblical conquest narratives, closely tied to the Exodus story, are theological constructs rather than accurate historical accounts.

In light of this evidence—or rather, lack thereof—many scholars propose that the Exodus story is a retrospective national myth, developed centuries later to provide a shared origin narrative for the diverse tribes of ancient Israel. Rather than emerging as a foreign group entering from Egypt, the early Israelites are now widely thought to have developed indigenously within Canaan itself. This view is supported by the continuity of material culture in early Israelite settlements, which closely resemble Canaanite patterns rather than those of a migrant or invading group.11 The Exodus story, therefore, functions more effectively as theological and political mythmaking—reaffirming divine deliverance, identity, and covenant—than as a literal historical account. While this interpretation challenges traditional readings, it enriches our understanding of how ancient societies constructed sacred history from fragments of memory, trauma, and ideology.

Egyptian Records and Silence

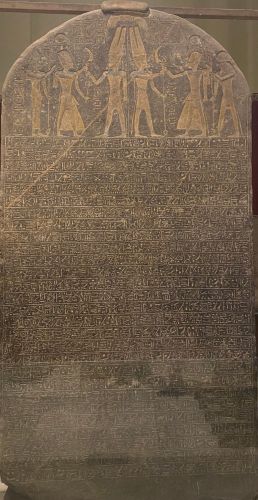

The absence of any direct reference to the Exodus in ancient Egyptian records has long been one of the most challenging issues for those seeking to historicize the biblical narrative. Given the scale and significance of the Exodus story—plagues, mass departure of slaves, and the drowning of Pharaoh’s army—one might expect some mention of these events in Egyptian administrative, monumental, or religious texts. However, a thorough review of extant inscriptions from the New Kingdom period, especially from the reigns of Pharaohs often associated with the story (such as Ramesses II or Merneptah), reveals no such acknowledgment. This silence is not only conspicuous but deeply problematic for efforts to correlate the biblical story with historical events.12 Ancient Egypt was a literate civilization with an obsession for recording its victories, religious observances, and state affairs, making the lack of reference to a national catastrophe particularly telling.

Apologists for the biblical narrative often argue that the Egyptians, like many ancient monarchies, only recorded events that enhanced the prestige of the pharaoh and his regime. According to this view, a massive slave rebellion and military defeat would have been intentionally omitted to preserve the king’s image as a divine and invincible ruler. While there is merit to the argument that ancient propagandistic traditions suppressed undesirable truths, the completeness of the silence remains troubling. Even in less official records—such as private tomb inscriptions, court documents, or administrative papyri—there is no allusion to widespread upheaval, economic distress, or mass flight of laborers, which would surely have had economic and social consequences.13 Instead, the records from this era often emphasize prosperity, military strength, and ritual stability, further distancing themselves from the implications of the Exodus narrative.

In contrast to the biblical portrayal of an oppressed Israelite population enslaved for centuries, Egyptian records do contain references to Asiatic (i.e., Semitic) populations living and working in Egypt. These groups, generally referred to as “Aamu” or “Shasu,” are depicted in a variety of roles—as laborers, traders, herders, and even soldiers—especially in the eastern Delta region. The famous tomb paintings at Beni Hasan (from the Middle Kingdom) and inscriptions from the city of Avaris (Tell el-Dab‘a) demonstrate that Semitic peoples entered Egypt over many generations, often through peaceful means and not in the dramatic terms suggested by the Exodus.14 Some scholars have suggested that the biblical Exodus may reflect a cultural memory of these migrations or even the expulsion of the Hyksos, a Semitic ruling class driven out of Egypt around 1550 BCE. However, the Hyksos were not slaves but foreign rulers, and their departure occurred centuries earlier than the traditional dating of the Exodus, raising questions about any direct continuity between the two episodes.15

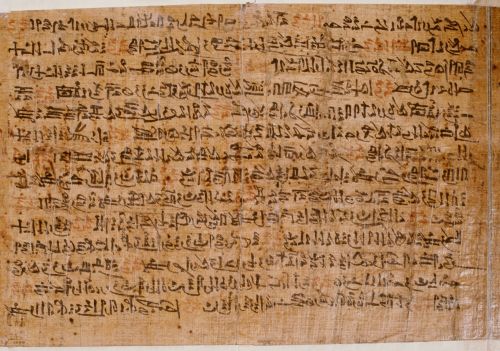

One Egyptian document that has sometimes been linked to the Exodus story is the “Admonitions of Ipuwer,” a poetic lament describing chaos, social upheaval, and natural disaster. This text, preserved in a single copy from the New Kingdom but thought to be a copy of a Middle Kingdom original, includes references to the Nile turning to blood and slaves fleeing their masters. While these details have led some to draw parallels with the biblical plagues and the escape of the Israelites, scholarly consensus holds that the Ipuwer Papyrus is a literary and rhetorical composition reflecting general themes of disorder, not a historical record.16 Its dating, ambiguity, and lack of specific geographic or cultural markers prevent it from being a reliable corroborative source for the Exodus account.

The silence of the Egyptian record must be weighed alongside the nature of ancient historiography and the purposes such records served. Egyptian texts were primarily theological and propagandistic, intended to reinforce cosmic order (ma’at) and royal legitimacy. In this light, one might expect unfavorable events to be minimized or omitted. However, even negative episodes—such as the Amarna Period’s religious upheaval or military defeats against foreign enemies—are sometimes acknowledged, albeit reframed. That no version of the Exodus appears, even in polemical or dismissive form, suggests either that the event never happened in the manner described, or that it was so minor that it failed to register in Egypt’s extensive bureaucratic and religious archives. This silence does not, in itself, disprove the Exodus narrative, but it seriously undermines its historical plausibility as a literal mass departure of enslaved Israelites from Egypt.17

Population in Canaan

One of the most significant problems with the historicity of the Exodus lies in the discrepancy between the biblical narrative and what the archaeological record reveals about population patterns in Canaan during the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages. The Bible describes a mass migration of Israelites from Egypt, their forty-year wandering in the wilderness, and their subsequent conquest and settlement of Canaan. According to this account, the Israelites arrived as a foreign people and displaced the existing Canaanite populations. However, archaeological data from the hill country of Canaan suggest a very different scenario: rather than showing signs of sudden invasion or resettlement by an external group, the evidence points to a gradual development of new settlements in the highlands by people who were likely indigenous to the region.18 These Iron Age I settlements (ca. 1200–1000 BCE) number over 200, and they show signs of continuity with Late Bronze Age Canaanite culture, rather than the cultural rupture one would expect from an influx of outsiders.

Excavations in key sites such as Ai, Jericho, and Lachish have failed to support the biblical conquest narrative that is supposed to follow the Exodus. For example, the city of Ai—claimed in the Book of Joshua to have been conquered and burned by the Israelites—was already abandoned centuries earlier and thus could not have been a target of conquest.19 Similarly, the destruction of Jericho, famously attributed to the Israelites through divine intervention, occurred well before the presumed time of the Exodus and conquest. Kathleen Kenyon’s mid-20th century excavations at Jericho revealed that the city was largely unoccupied during the Late Bronze Age, directly contradicting the biblical story.20 Moreover, the few Canaanite cities that do show signs of destruction around 1200 BCE—such as Hazor—were the exception rather than the rule and may be more reasonably attributed to regional conflicts, social upheaval, or internal rebellion rather than to a unified Israelite military campaign.

Further complicating the biblical picture is the continuity of material culture between Canaanite and early Israelite settlements. Pottery styles, architectural forms, and agricultural tools found in early Israelite villages are remarkably similar to those of their Canaanite neighbors. This continuity suggests not a dramatic cultural replacement, as one might expect following a foreign conquest, but rather an evolution of existing Canaanite society into what would later be called “Israelite.”21 The absence of pig bones in many of these highland sites has often been used to argue for a distinct Israelite identity, yet even this is debated, as dietary habits alone cannot account for complex ethnic distinctions. The broader picture is one of cultural overlap, adaptation, and endogenous development, not a sharp break caused by a migrating population from Egypt.

The settlement pattern in the highlands of Canaan also contradicts the Exodus story’s chronology. The dramatic increase in small, unwalled villages in the hill country during the late 13th and early 12th centuries BCE corresponds more closely with a period of regional collapse and decentralization throughout the eastern Mediterranean, rather than with the organized invasion described in the Book of Joshua. Scholars like Israel Finkelstein argue that these settlements were likely founded by displaced rural Canaanites responding to environmental, economic, and political pressures, not by a horde of liberated Egyptian slaves.22 These early Israelites appear to have emerged from within Canaanite society itself, part of a larger transformation in response to the fall of major city-states and the weakening of Egyptian imperial control in the region.

The cumulative weight of archaeological data strongly suggests that the Exodus story, as presented in the Bible, does not align with the known history of population movement, settlement, and material culture in Canaan. Rather than a miraculous escape and conquest, the emergence of Israel was a complex, gradual process involving indigenous Canaanite groups developing a new socio-political identity during a time of regional instability. The biblical narrative, therefore, is likely a retrojection—a theological origin myth composed centuries after the events it claims to recount, meant to forge a shared memory and national identity for disparate tribal groups.23 This does not diminish the power or cultural significance of the Exodus story, but it does call into question its literal historical accuracy when compared with the archaeological and demographic record.

Internal Origins of Israel

The theory of the internal origin of Israel posits that the early Israelites did not enter Canaan as an external, conquering group, but rather emerged from within the indigenous Canaanite population during the collapse of the Late Bronze Age social and political order. This view challenges the traditional biblical account of the Exodus, which portrays Israel as a people forged in Egypt, liberated by divine intervention, and introduced into Canaan by conquest. Instead, the internal emergence model holds that the early Israelites were Canaanites who gradually differentiated themselves through new social, economic, and religious practices in response to the breakdown of urban life and imperial control in the region around 1200 BCE.24 The archaeological evidence increasingly supports this view, revealing a high degree of cultural continuity between Late Bronze Age Canaanite settlements and the early Iron Age sites attributed to the Israelites.

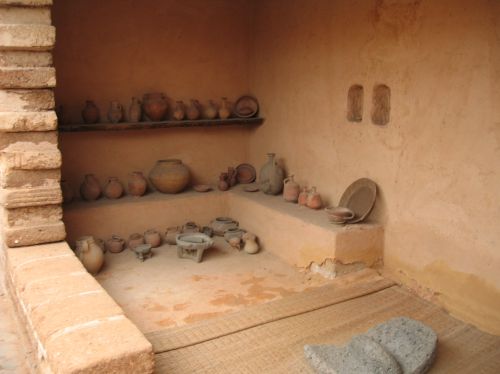

The settlement patterns of early Israelite communities bolster the case for internal development. In the central hill country of Canaan, archaeologists have uncovered numerous small, unwalled villages that began to appear in the late 13th century BCE. These sites differ from the large, fortified cities of the previous age and suggest a significant demographic shift toward more egalitarian, subsistence-level living. The architecture and material culture of these sites—such as pottery styles, storage silos, and house layouts—indicate a break with the elite-driven urbanism of the Canaanite city-states but do not suggest the arrival of a foreign people with a radically different cultural toolkit.25 These communities appear to have evolved organically as part of a local process of adaptation and reorganization, likely involving displaced peasants, pastoralists, and lower-class Canaanites seeking refuge from political and economic turmoil.

Crucially, the early Israelite highland settlements demonstrate significant cultural overlap with their Canaanite neighbors. This includes shared ceramic forms, religious symbols, and agricultural practices. There is no sharp boundary in the material record that would suggest a sudden influx of a distinct group from outside the region. Even the oft-cited absence of pig bones in these sites—previously interpreted as a marker of Israelite ethnic identity—is now viewed by many scholars as an oversimplified and inconclusive indicator, given that similar abstentions are found in other regional populations and may have had dietary, ecological, or economic motivations rather than ideological ones.26 These continuities point to a scenario in which early Israelites were part of the broader Canaanite population, gradually coalescing into a new social identity over generations.

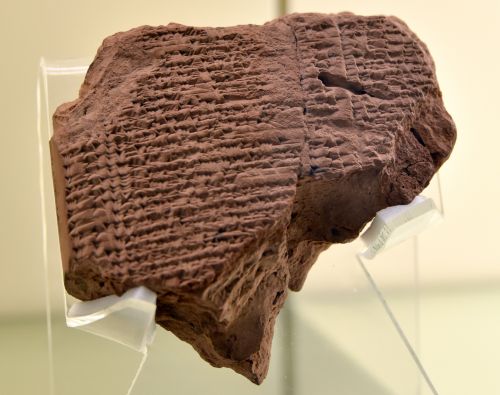

Linguistic and epigraphic evidence further supports the internal origin theory. The earliest inscriptions in the Hebrew language, including the Gezer Calendar and other Proto-Canaanite texts, do not reflect foreign influence but are rooted in the West Semitic language continuum native to Canaan. Additionally, the names of early Israelite figures, both in the Bible and in extrabiblical inscriptions, are often Canaanite in form and meaning.27 This linguistic continuity reinforces the archaeological picture: the Israelites did not bring a foreign tongue with them from Egypt but rather spoke a dialect of the languages already present in the region. The development of Israelite religion also seems to reflect a reformulation of existing Canaanite cultic practices, with the god Yahweh gradually assuming prominence, possibly as a synthesis of Canaanite and Midianite religious ideas, rather than a wholly imported deity introduced after the Exodus.

The internal origins model not only contradicts the Exodus story but also suggests that the narrative itself was likely a later ideological construct, developed in the Iron Age or later to provide a unifying national myth for a diverse and regionally scattered population. By presenting the Israelites as a people chosen by a powerful deity who liberated them from foreign bondage, the Exodus narrative helped forge a sense of identity and divine purpose. Yet from a historical perspective, this mythologized account obscures the more mundane but illuminating reality of sociopolitical evolution within Canaanite society. In this sense, the Israelites were not outsiders who invaded the land, but insiders who redefined it—and themselves—through centuries of adaptation, resistance, and memory.28

The Exodus as National Myth and Theological Construct

The Exodus narrative, as found in the Hebrew Bible, functions less as a reliable historical account and more as a foundational national myth that constructs a collective identity and theological framework for ancient Israel. Myths of national origin are a common feature among peoples seeking to explain their existence, purpose, and cohesion. For Israel, the Exodus story provided a powerful narrative of liberation from oppression, divine election, and covenantal destiny. In this sense, the story served as a unifying myth that offered both a shared past and a theological charter for a people often divided by tribal, regional, and political factions.29 The imagery of a journey from slavery to freedom under the leadership of a divinely appointed prophet resonated deeply, allowing for the development of a distinctive Israelite consciousness rooted in moral obligation and divine favor.

The Exodus story is also carefully constructed to affirm monotheism and to elevate Yahweh as the supreme deity who acts on behalf of His chosen people. This is evident in the repeated refrain that God delivered Israel “with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm,” emphasizing divine power and intentionality. The plagues against Egypt serve not just to punish Pharaoh, but to systematically dismantle the authority of Egyptian gods, thereby reinforcing Yahweh’s supremacy.30 The wilderness experience, in which Israel receives the Law at Sinai, further establishes a theological and moral framework that distinguishes Israel from surrounding nations. Thus, the Exodus functions as a theodicy—a narrative defense of divine justice—and a polemic against polytheism. The story becomes less about historical memory and more about theological messaging and spiritual formation.

There is also a strong case to be made that the Exodus narrative was composed or substantially shaped during the Babylonian exile or the early post-exilic period, when the Israelites were once again a displaced and oppressed people. Scholars like Michael Fishbane and Jon Levenson have argued that the story operates as a myth of hope, portraying a God who redeems and restores His people from bondage and chaos.31 In this context, the Exodus becomes a story not of the past but of the present and future—a theological template through which Israel could understand its suffering and anticipate its deliverance. The creation of such a myth served not only to bind the exilic community together, but also to assert that Israel’s God remained active, powerful, and faithful, even in foreign lands under foreign rule.

The Exodus also functions as an ideological critique of empire and human authority. Pharaoh is portrayed as the archetype of oppressive power, whose resistance to divine will leads to ruin. In contrast, Moses becomes a model of prophetic leadership, obedience, and moral courage. These portrayals align the story with broader themes of justice, liberation, and covenant responsibility. The narrative’s theological intent is evident in its dramatic contrasts: Egypt’s grandeur falls, while the powerless Israelites rise; divine law triumphs over human tyranny; and freedom is portrayed not as license but as obedience to God. These are not accidental features, but deliberate literary and theological constructs designed to shape the identity and ethos of a people in transition.32

While the historical Exodus as described in the Bible lacks direct archaeological corroboration, its enduring significance lies in its mythic and theological functions. It offers a narrative of national election, divine intervention, moral law, and hopeful deliverance that transcends historical verifiability. Much like the founding myths of other ancient cultures—such as Rome’s Aeneid or Athens’ autochthony—the Exodus shapes memory more than it reflects history. It articulates what Israel was meant to be, what its God demanded of it, and how it understood its place in the world. As such, the Exodus endures not because it is historically provable, but because it is theologically indispensable and symbolically powerful.33

Conclusion

Despite its profound cultural and theological significance, the Exodus story lacks corroboration from the archaeological and historical record. No evidence has been found for a large-scale migration of Israelites from Egypt, the wandering in the Sinai, or the conquest of Canaan. Egyptian records are silent on the matter, and the archaeological record of both Egypt and Canaan contradicts the biblical narrative.

Rather than discrediting the Exodus as meaningless, this lack of evidence invites a more nuanced understanding of ancient Israelite identity and memory. The Exodus, in this view, is a foundational myth—a symbolic narrative constructed from fragments of history, oral traditions, and theological ideals. It speaks to the human need to make sense of suffering, displacement, and hope through story. As such, the Exodus remains a central narrative not because it is historically true, but because it is spiritually resonant.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Nahum M. Sarna, Exploring Exodus: The Origins of Biblical Israel (New York: Schocken Books, 1986), 7–12.

- Richard Elliott Friedman, Who Wrote the Bible? (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1997), 114–120.

- Exodus 12:37 (New Revised Standard Version). See also Kenneth A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003), 245.

- Jon D. Levenson, Sinai and Zion: An Entry into the Jewish Bible (Minneapolis: Winston Press, 1985), 17–26.

- Carol Meyers, Exodus (New Cambridge Bible Commentary; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 321–336.

- Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts (New York: Free Press, 2001), 63–70.

- Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, 310-316.

- William G. Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001), 38–45.

- Kathleen M. Kenyon, Digging Up Jericho (London: Ernest Benn, 1957), 261–262.

- Amnon Ben-Tor, “Excavating Hazor, Part Two: Did the Israelites Destroy the Canaanite City?” Biblical Archaeology Review 25, no. 3 (1999): 26–39.

- Carol Meyers, Discovering Eve: Ancient Israelite Women in Context (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 45–47.

- Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 408–410.

- James K. Hoffmeier, Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 83–85.

- Manfred Bietak, “The Hyksos and Their New Capital at Tell el-Dab‘a,” Biblical Archaeology Review 18, no. 3 (1992): 22–41.

- Eric H. Cline, From Eden to Exile: Unraveling Mysteries of the Bible (Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2007), 76–78.

- Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975), 149–163.

- Finkelstein and Silberman, The Bible Unearthed, 70-75.

- Finkelstein and Silberman, The Bible Unearthed, 103-106.

- William G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003), 46–49.

- Kenyon, Digging Up Jericho, 261-264.

- Ann E. Killebrew, Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, Philistines, and Early Israel, 1300–1100 B.C.E. (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2005), 179–183.

- Israel Finkelstein, The Archaeology of the Israelite Settlement (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1988), 340–348.

- Lester L. Grabbe, Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It? (London: T&T Clark, 2007), 52–56.

- William G. Dever, Did God Have a Wife? Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2005), 99–103.

- Finkelstein and Silberman, The Bible Unearthed, 107-111.

- Killebrew, Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity, 185-189.

- Mark S. Smith, The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2002), 36–39.

- Grabbe, Ancient Israel, 57-60.

- Jan Assmann, Moses the Egyptian: The Memory of Egypt in Western Monotheism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 5–8.

- Richard Elliott Friedman, The Bible with Sources Revealed (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2003), 94–97.

- Levenson, Sinai and Zion, 56-60.

- Michael Fishbane, Biblical Text and Texture: A Literary Reading of Selected Texts (New York: Schocken Books, 1979), 87–91.

- Thomas L. Thompson, The Mythic Past: Biblical Archaeology and the Myth of Israel (New York: Basic Books, 1999), 116–119.

Bibliography

- Assmann, Jan. Moses the Egyptian: The Memory of Egypt in Western Monotheism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Ben-Tor, Amnon. “Excavating Hazor, Part Two: Did the Israelites Destroy the Canaanite City?” Biblical Archaeology Review 25, no. 3 (1999): 26–39.

- Bietak, Manfred. “The Hyksos and Their New Capital at Tell el-Dab‘a.” Biblical Archaeology Review 18, no. 3 (1992): 22–41.

- Cline, Eric H. From Eden to Exile: Unraveling Mysteries of the Bible. Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2007.

- Dever, William G. Did God Have a Wife? Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2005.

- Dever, William G. What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001.

- Dever, William G. Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003.

- Finkelstein, Israel. The Archaeology of the Israelite Settlement. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1988.

- Finkelstein, Israel, and Neil Asher Silberman. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New York: Free Press, 2001.

- Fishbane, Michael. Biblical Text and Texture: A Literary Reading of Selected Texts. New York: Schocken Books, 1979.

- Friedman, Richard Elliott. The Bible with Sources Revealed. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2003.

- Friedman, Richard Elliott. Who Wrote the Bible? San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1997.

- Grabbe, Lester L. Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It? London: T&T Clark, 2007.

- Hoffmeier, James K. Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Kenyon, Kathleen M. Digging Up Jericho. London: Ernest Benn, 1957.

- Killebrew, Ann E. Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, Philistines, and Early Israel, 1300–1100 B.C.E. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2005.

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003.

- Levenson, Jon D. Sinai and Zion: An Entry into the Jewish Bible. Minneapolis: Winston Press, 1985.

- Lichtheim, Miriam. Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975.

- Meyers, Carol. Discovering Eve: Ancient Israelite Women in Context. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Meyers, Carol. Exodus. New Cambridge Bible Commentary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992.

- Sarna, Nahum M. Exploring Exodus: The Origins of Biblical Israel. New York: Schocken Books, 1986.

- Smith, Mark S. The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel. 2nd ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2002.

- Thompson, Thomas L. The Mythic Past: Biblical Archaeology and the Myth of Israel. New York: Basic Books, 1999.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.05.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.