The story of Shiloh is a somber testament to the peril of blind obedience.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

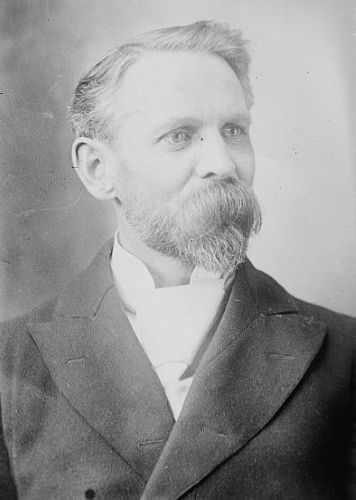

In the landscape of American religious history, apocalyptic movements have repeatedly surfaced, driven by charismatic leaders convinced of an impending eschaton—the end of the world. Among the more enigmatic and tragic of these figures is Frank W. Sandford (1862–1948), a self-proclaimed prophet whose radical millennialist vision gave rise to a sectarian Christian community known as “The Kingdom.” Sandford’s movement exemplified the dangers of unchecked spiritual authority, extreme asceticism, and the dark allure of apocalyptic certainty.

This essay explores the origins, beliefs, practices, and historical significance of Frank Sandford’s apocalyptic sect, focusing on its theological foundations, communal experiments, and eventual collapse. In doing so, it highlights broader themes in American religious culture, including millennialism, charismatic leadership, and the complex intersection between spirituality and authoritarianism.

Origins and Early Life of Frank Sandford

Frank Weston Sandford was born on October 2, 1862, in Bowdoinham, Maine, a small New England town situated in the conservative religious culture of rural postbellum America. Raised in a devout Baptist household, Sandford was exposed early to the rigid piety and evangelical fervor characteristic of northeastern Protestantism in the second half of the nineteenth century. His upbringing was deeply influenced by the region’s tradition of revivalism and the residual energies of the Second Great Awakening, which had only recently subsided. These early religious experiences cultivated in Sandford a sense of divine purpose and a vision of moral order rooted in scriptural literalism and spiritual striving. As a boy, he was said to exhibit a precocious intensity in matters of faith, often engaging in fervent prayer and scriptural study beyond what was typical for a child his age.1

Sandford’s formal education began at Bates College in Lewiston, Maine, an institution affiliated with the Free Will Baptist tradition. There he studied liberal arts with a focus on theology and classical languages, further sharpening his scriptural literacy and public speaking skills. However, his intellectual trajectory was soon shaped less by academic inquiry and more by the emergent Holiness and Higher Life movements gaining traction among evangelical Protestants in the late 19th century. These movements emphasized sanctification as a second work of grace, divine healing, and a personal, emotional experience of God—all elements that would become central to Sandford’s later ministry.2 Disillusioned with the perceived spiritual complacency of denominational religion, Sandford increasingly embraced the belief that God was calling him to a special work of restoration and prophecy.

Following his graduation, Sandford enrolled in Cobb Divinity School, also associated with Bates College, where he studied for the Baptist ministry. Yet even here he found the theological instruction too cautious and overly academic. During this period, he encountered texts and sermons by figures such as Charles Finney and A.J. Gordon, whose emphasis on revivalism and immediate divine action inspired in him a desire for direct spiritual leadership.3 In 1893, Sandford was ordained as a Baptist minister, but within a few years he had already begun to distance himself from institutional church structures. He began preaching independently, drawing crowds with his fiery sermons and prophetic tone. His preaching increasingly emphasized themes of repentance, spiritual warfare, and apocalyptic imminence, foreshadowing the more radical theology he would later articulate.

Sandford’s shift from traditional Baptist minister to prophetic leader was marked by a dramatic spiritual experience in 1893, which he claimed constituted a divine calling to build the Kingdom of God on earth. According to his own testimony, he heard the audible voice of God instructing him to separate from the worldly church and prepare a people for the Second Coming of Christ.4 This experience became the foundational moment of his later sectarian movement. He began referring to himself in messianic terms, adopting titles like “Elijah” and “God’s Anointed,” and saw himself as the last-day prophet who would restore apostolic Christianity before the return of Jesus. His earliest followers were drawn to his confidence, charismatic authority, and uncompromising spirituality—traits that distinguished him from more moderate evangelical leaders of his time.

By 1896, Sandford had attracted a significant number of adherents and had begun laying the groundwork for what would become “The Kingdom,” a utopian Christian community governed by strict spiritual discipline and total submission to divine authority—as mediated through Sandford himself.5 That same year, he and his followers established the community of Shiloh in Durham, Maine, which would serve as the geographical and spiritual heart of the movement. The origins of Shiloh were rooted not only in Sandford’s radical eschatology but also in his early experiences of dissatisfaction with mainstream Protestantism. His upbringing in a morally rigid yet spiritually dry environment, combined with his exposure to revivalist impulses during his education, forged the psychological and theological basis for his sectarian break. Sandford’s early life thus provides critical insight into the spiritual extremism that would define his later career—a potent blend of sincere conviction, authoritarian temperament, and apocalyptic vision.

The Founding of “The Kingdom” and Shiloh

After his decisive spiritual awakening in 1893, Sandford fully embraced his perceived divine mission to establish a purified, end-times community of believers. He began preaching across New England with increasing urgency, proclaiming the imminent return of Christ and calling for the restoration of apostolic Christianity. Drawing from premillennialist theology and his belief in direct divine revelation, Sandford argued that God had chosen him to lead a new spiritual order, one not bound by denominational structures but wholly submissive to divine guidance. This conviction culminated in the founding of “The Kingdom,” an informal yet rigidly theocratic organization that rejected all worldly affiliations. Sandford’s followers were required to renounce their former lives, sever ties with traditional churches, and submit wholly to what he declared was God’s plan for a last-days remnant.6

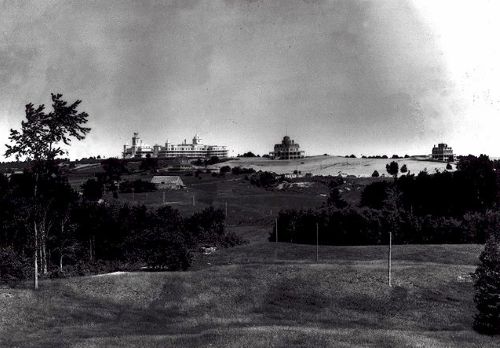

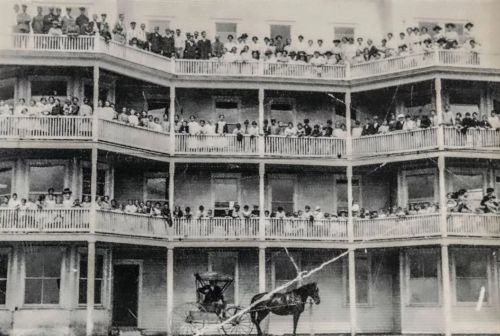

The physical manifestation of “The Kingdom” was Shiloh, a religious community constructed in Durham, Maine, beginning in 1896. Sandford selected the location for its seclusion, which he saw as essential to spiritual purification and communal discipline. Over time, Shiloh grew into a complex of dormitories, chapels, classrooms, and agricultural facilities, housing as many as 600 people at its peak. Sandford named the community after the biblical city of Shiloh, where the Ark of the Covenant once resided—implying that his compound, too, was a vessel of divine presence.7 The architectural center of Shiloh was a massive wooden temple known as “The Temple,” which could hold over 1,000 congregants and served as the site of daily worship, prayer vigils, and prophetic declarations. From this headquarters, Sandford exercised total authority over his followers, claiming that every decision was divinely inspired and required no human accountability.

Life at Shiloh was characterized by rigorous spiritual discipline, communal living, and a pervasive atmosphere of eschatological expectation. Residents lived under a strict schedule of prayer, fasting, Bible reading, and physical labor. Sandford emphasized spiritual “cleansing” through suffering and sacrifice, sometimes ordering extended fasts lasting several days or weeks.8 Medical treatment was eschewed in favor of divine healing, and any dissent or questioning of Sandford’s leadership was considered rebellion against God himself. He maintained a doctrine of absolute spiritual hierarchy, with himself as the mouthpiece of divine will and his inner circle acting as enforcers of spiritual and social conformity. Over time, Shiloh developed into a self-contained theocracy, complete with its own internal judiciary, school system, and ecclesiastical rites—all orchestrated by Sandford’s vision of a restored biblical order.9

While Sandford’s rhetoric often invoked love, holiness, and devotion, life within Shiloh was frequently harsh and authoritarian. Food shortages, poor sanitation, and medical neglect were common. Children and elderly followers were not exempt from the demanding lifestyle. Punishments for perceived spiritual failings included isolation, public humiliation, or expulsion from the community. Sandford’s theology increasingly stressed obedience and spiritual warfare, casting external society—and often even family members outside the community—as under Satan’s control.10 He frequently preached about the need to “separate the wheat from the chaff,” using this motif to justify purges within the community. As Shiloh grew, it began sending missionaries across the United States and abroad, further spreading Sandford’s vision of a purified Kingdom people. Yet the expanding mission also placed considerable strain on the community’s finances and infrastructure, problems exacerbated by Sandford’s extravagant and often arbitrary projects, which he insisted were divinely mandated.

By the early 1900s, Shiloh had become a prominent—and increasingly controversial—religious commune. It drew intense scrutiny from local authorities, the press, and disaffected former members, many of whom accused Sandford of spiritual abuse, coercive control, and negligence. Reports of child deaths, malnourishment, and forced fasting began to surface in the media.11 Nevertheless, Sandford refused to compromise or alter his practices, insisting that all opposition was evidence of persecution and proof of his divine mission. His control over The Kingdom remained absolute, and his apocalyptic proclamations grew ever more urgent. In many ways, the founding and rise of Shiloh represent the high point of Sandford’s religious influence: a rare and radical attempt to construct an end-times theocracy on American soil, built on biblical literalism, charismatic authority, and millennial expectation.

Theological Beliefs and Millennialism

Sandford’s theological worldview was rooted in a radical form of biblical literalism, deeply influenced by Holiness teachings and the late 19th-century surge in premillennial dispensationalism. He believed that Scripture provided a direct, unmediated roadmap for life, prophecy, and divine governance, requiring no interpretation beyond what he declared was spiritually revealed truth. While originally trained in Baptist theology, Sandford increasingly rejected denominational frameworks in favor of a direct divine mandate. His doctrinal emphasis on personal holiness, spiritual warfare, and the absolute authority of God—as expressed through his own leadership—placed him at odds with mainstream Protestantism. Central to his theology was the conviction that he had been divinely chosen to lead a restored remnant of the true Church in preparation for Christ’s imminent return.12 This elect group, “The Kingdom,” would be purified through suffering and obedience and would usher in the millennial reign of Christ from a literal Mount Zion—spiritually prefigured in his Shiloh community.

Sandford’s millennialism was premillennial in structure but highly personalized in its prophetic details. Like many evangelicals of the era, he believed that the world was in moral and spiritual decline and that Christ would soon return to establish a literal thousand-year reign of peace, as described in Revelation 20. However, Sandford uniquely cast himself as a forerunner to Christ—an Elijah-like figure whose mission was to “prepare the way” for the Messiah by assembling a purified people.13 Drawing upon Old Testament imagery and New Testament prophecy, he developed a robust eschatology that included judgments upon sinful nations, the rise of spiritual Babylon (identified with the institutional church), and the persecution of the righteous remnant. Sandford often referred to current events—wars, famines, and natural disasters—as signs of the impending apocalypse, integrating newspaper headlines into his sermons as fulfillments of scriptural prophecy.14 This intense eschatological fervor fueled the strict lifestyle he demanded of his followers, whom he warned would be judged more harshly for their failure to remain spiritually vigilant.

A particularly distinctive feature of Sandford’s theology was his belief in “the Manchild Company,” a concept drawn from Revelation 12 and other apocalyptic texts. He interpreted the “manchild” born of the woman as a metaphor for a small, spiritually perfected group of believers—his followers—who would be caught up to God and become co-regents with Christ in the coming millennial kingdom.15 This elite company, he preached, would be invincible in spiritual warfare, protected from the wrath of Satan, and endowed with supernatural authority. He claimed that Shiloh was the womb in which this manchild company was being formed, purified through prayer, fasting, and submission to divine will. The implication, never far from the surface, was that Sandford himself was the spiritual father of this company and the sole human conduit of God’s revelatory authority. This theology served not only to legitimize his total control over the community but also to isolate his followers from outside influence or critique.

Another important aspect of Sandford’s belief system was his doctrine of divine healing and anti-medicalism. Influenced by the Holiness and Faith Cure movements, he taught that all physical ailments were either the result of sin or spiritual trial and that complete healing could be attained only through prayer and faith.16 Consequently, residents of Shiloh were forbidden to seek medical treatment; to do so was to lack faith in God’s provision. This theology of suffering as sanctification was particularly severe and sometimes fatal. Children, elderly individuals, and the infirm were denied basic medical care, and deaths were frequently explained away as part of God’s mysterious plan. Sandford extended this belief into a broader theology of martyrdom and purification, insisting that God allowed suffering to perfect His people and ready them for millennial glory. This emphasis on divine chastening reinforced the authoritarian nature of Sandford’s regime and provided theological justification for the extreme asceticism practiced at Shiloh.

Perhaps most importantly, Sandford’s millennialism was not passive but profoundly active. Unlike earlier millenarians who withdrew from society to await divine intervention, Sandford believed that Christ’s return was contingent upon the faithful obedience of his chosen people.17 In other words, human action—guided by prophetic leadership—was a necessary precondition for the inauguration of the Millennium. This concept of “cooperation with the divine” gave Sandford’s theology an intensely urgent and mobilizing quality. His followers were not merely preparing for Christ’s return; they were participating in its realization. Shiloh was thus both a refuge from the corrupt world and a launching pad for a new spiritual order. Sandford’s theological framework blurred the lines between prophetic expectation and realized eschatology, presenting his own leadership and community not as a prelude to the Kingdom, but as its very foundation.

Missionary Zeal and Maritime Tragedy

Sandford’s apocalyptic vision extended far beyond the secluded hills of Maine. Convinced that he was raising up the final generation of God’s chosen people, he launched an aggressive missionary campaign to spread “The Kingdom” across the globe. Inspired by both the Great Commission and a self-fashioned sense of divine mandate, Sandford viewed missionary activity not merely as evangelical outreach but as an essential act of spiritual warfare in preparation for Christ’s return.18 He believed that the gospel must be proclaimed to all nations before the Second Coming could occur, and his followers—many of them young and fervently devoted—were trained to travel with minimal support, armed only with prayer and Scripture. This missionary zeal reached its apex with the commissioning of a schooner called the Coronet, a 130-foot vessel that Sandford purchased and renamed for God’s purposes. The ship, refitted to serve as a floating seminary and temple, became the centerpiece of Sandford’s maritime evangelism.

The Coronet was not simply a missionary vessel; it was a floating extension of Shiloh itself, governed by the same rigorous spiritual disciplines. Sandford declared that God had commanded him to sail around the world proclaiming the gospel and claiming territories for Christ. The voyage was framed as a prophetic act of spiritual conquest—a literal claiming of the nations in the name of God’s Kingdom.19 Life aboard the Coronet mirrored that of Shiloh: constant prayer, fasting, and unwavering obedience to Sandford’s divine revelations. The ship’s crew consisted of men, women, and children, all of whom were subjected to severe physical and spiritual demands during the voyage. Sandford insisted that he had no need for navigational training or medical supplies, for God would guide and sustain them. He called it a “faith voyage,” relying solely on divine provision and rejecting traditional planning or maritime prudence.

The missionary voyage, however, quickly turned perilous. Between 1905 and 1906, the Coronet traveled thousands of miles with minimal rations, no professional seamen, and without stopping at major ports for supplies or repairs. At one point, Sandford ordered the ship to sail across the Atlantic to Africa, despite signs of illness and dwindling provisions.20 Several crew members fell gravely ill, including children, and Sandford forbade the use of medicine or disembarkation for medical help. The result was a humanitarian disaster: six crew members died from scurvy and related complications. Rather than return home or seek outside assistance, Sandford interpreted the suffering as divine chastisement and spiritual testing. He frequently cited the biblical accounts of Job and Paul, insisting that the hardships only affirmed God’s hand in their journey. For Sandford, the voyage’s suffering was not a failure but a purifying crucible for a holy remnant.

News of the deaths aboard the Coronet and Sandford’s refusal to seek aid shocked the public and attracted national scrutiny. When the ship finally returned to port in 1906, media coverage portrayed the journey as a grotesque example of religious extremism and clerical tyranny.21 The U.S. government initiated an investigation, and Sandford was ultimately indicted on manslaughter charges for the deaths at sea. He was convicted in 1911 and sentenced to ten years in federal prison, though he served just under seven.22 The trial revealed disturbing details about life aboard the ship and the depth of Sandford’s control over his followers, many of whom defended him despite the suffering they endured. The Coronet voyage, once heralded by Sandford as a triumphant act of divine conquest, had become a symbol of religious fanaticism gone tragically awry.

Despite the disaster, Sandford remained largely unrepentant. Even during his imprisonment, he continued to write to his followers, issuing spiritual directives and proclaiming that his suffering was part of God’s providential plan. After his release in 1918, he returned to Shiloh, though the community had drastically dwindled in size and influence. The Coronet voyage marked a turning point in the history of Sandford’s movement: from spiritual revival and community-building to decline and disillusionment.23 The missionary enterprise that had once energized Shiloh and inspired hundreds to sacrifice everything now stood as a cautionary tale. Yet for those who remained faithful to Sandford’s teachings, the voyage remained shrouded in divine mystery—a chapter of martyrdom in the unfolding drama of millennial redemption. The maritime tragedy served as both the zenith and unraveling of Sandford’s utopian project, forever linking his legacy with one of the most harrowing episodes in American religious history.

Decline and Legacy

Sandford’s movement, once bursting with millennial energy and divine certitude, began a slow but irreversible decline in the years following his imprisonment. After his release in 1918, Sandford returned to Shiloh only to find it a shadow of its former self. The community had been decimated by negative press, government scrutiny, and the loss of public trust after the Coronet tragedy.24 Many of his former followers had left, disillusioned by the suffering, legal consequences, and failed promises. Sandford, now physically weakened and increasingly authoritarian, continued to preach and write, but the magnetic fervor of his earlier years had faded. His attempts to reinvigorate “The Kingdom” fell flat in a postwar America increasingly skeptical of religious utopianism. The very attributes that had once defined Shiloh—self-sacrifice, separation, and apocalyptic expectation—had become liabilities in an era increasingly oriented toward secular modernity and institutional religion.

By the 1920s, Sandford’s leadership had taken on a more insular and esoteric character. He focused inward, writing long prophetic treatises and elaborating ever more complex revelations about his role in the end times.25 He began to distance himself from earlier claims of messianic identification, even as he subtly reaffirmed his role as the sole divine mouthpiece for the elect. While a core of loyalists remained, the community’s numbers dwindled. Financial strain, legal costs, and the reputational damage from the manslaughter conviction made it increasingly difficult to maintain the Shiloh complex. In 1920, the court seized the Shiloh property to satisfy debts, and the once-thriving commune was eventually dismantled.26 Its buildings were either abandoned or repurposed by local authorities, and the grand tabernacle—once a symbol of holy destiny—was torn down. Sandford relocated his remaining followers to smaller outposts, attempting to preserve what he now described as a “spiritual Shiloh,” no longer tied to place but to obedience.

Though Sandford died in 1948, the movement he founded did not vanish completely. His most faithful followers carried on his teachings under the name “The Kingdom,” preserving his writings and continuing a much-diminished form of the original community structure.27 These remnant groups remained committed to Sandford’s interpretation of biblical prophecy, his emphasis on holiness and suffering, and the notion of a spiritual remnant preparing for the Second Coming. While they did not attract many new converts, their survival demonstrates the powerful grip that apocalyptic leadership can exert on devoted followers. Some branches, such as the “Kingdom Christian Ministries,” continue to meet today, preserving elements of Sandford’s theological framework while distancing themselves from his more controversial actions and the maritime tragedy.28 In this way, Sandford’s legacy has been both repudiated and sustained—his errors acknowledged, yet his vision still regarded by some as divinely inspired.

Historiographically, Sandford has garnered increasing attention from scholars interested in religious utopianism, millennialism, and the darker dimensions of charismatic authority. Historians and sociologists alike have compared his movement to other apocalyptic sects of the era, noting both its similarities to and deviations from more mainstream evangelical currents.29 While groups like the Shakers or Oneida are often cited for their communal structures and social experimentation, Sandford’s Kingdom has been singled out for its intense authoritarianism and theological rigidity. His absolutist leadership, anti-medical stance, and fixation on divine punishment have invited comparisons to later religious leaders such as Jim Jones and David Koresh, although Sandford did not end in outright violence. Nonetheless, his life and ministry serve as a powerful case study in how sincere religious conviction, when fused with unchecked authority and eschatological urgency, can lead to physical, psychological, and spiritual harm.

In the broader landscape of American religious history, Frank Sandford represents a convergence of themes that continue to resonate: utopian idealism, charismatic control, radical literalism, and millennial expectation.30 While his movement ultimately collapsed under the weight of its own extremism, it also testifies to the enduring human hunger for meaning, purity, and cosmic purpose. Shiloh and the Coronet are now largely forgotten outside scholarly circles, but the questions Sandford raised—about divine authority, communal living, and spiritual destiny—remain potent. His legacy invites reflection on both the possibilities and perils of apocalyptic religion in the modern world. For some, he is a tragic cautionary tale of delusion and abuse; for others, a misunderstood prophet whose vision was never fully realized. Either way, Frank Sandford and the Apocalyptic Kingdom occupy a unique, if sobering, chapter in the story of American faith.

Analysis: Charisma, Power, and the American Apocalyptic Imagination

Frank Sandford’s life and movement illustrate several recurrent patterns in American religious history. His rise coincided with a broader wave of religious enthusiasm at the turn of the 20th century, a time when many Americans felt disoriented by industrialization, immigration, and social change. Apocalyptic leaders like Sandford offered certainty, community, and purpose in an age of upheaval.

His appeal was also deeply psychological. For many, the rigor of Shiloh offered a sense of purity and direction. But Sandford’s charisma crossed into spiritual abuse, as his need for control and validation increasingly eclipsed the well-being of his followers.

Historically, Sandford’s movement also underscores the tension between individual religious freedom and societal protection. The U.S. has long championed religious pluralism, but the suffering and deaths at Shiloh and aboard the Coronet forced the state to intervene—revealing the limits of tolerance when religious authority becomes dangerous.

Conclusion

Frank Sandford’s apocalyptic sect stands as a striking example of how deeply held spiritual convictions can both inspire and devastate. His desire to build the Kingdom of God on Earth was rooted in a genuine religious longing, but distorted by authoritarianism, isolationism, and hubris.

In studying Sandford, we confront enduring questions: How should society respond to charismatic religious movements? What safeguards are necessary to protect the vulnerable? And how do spiritual ideals become corrupted when one man claims to speak for God? The story of Shiloh is a somber testament to the power of belief—and the peril of blind obedience.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Stephen J. Paterwic, The A to Z of the Shakers (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2009), 244.

- Edith L. Blumhofer, Restoring the Faith: The Assemblies of God, Pentecostalism, and American Culture (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 31–32.

- Barry Morton, “Kingdoms in Conflict: The Rise and Fall of Frank Sandford’s Shiloh,” Journal of Millennial Studies 2, no. 1 (Spring 1999): 7–8.

- John W. Crowley, Empty Houses: Theatrical Failure and the Novel (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991), 77.

- Donald E. Pitzer, ed., America’s Communal Utopias (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 405.

- Morton, “Kingdoms in Conflict,” 9.

- Pitzer, ed., America’s Communal Utopias, 408.

- Paterwic, The A to Z of the Shakers, 244.

- Blumhofer, Restoring the Faith, 36-37.

- Susan Juster, Doomsayers: Anglo-American Prophecy in the Age of Revolution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), 214.

- Morton, “Kingdoms in Conflict,” 12–13.

- Morton, “Kingdoms in Conflict,”, 14.

- Blumhofer, Restoring the Faith, 42-43.

- Pitzer, ed., America’s Communal Utopias, 412.

- Juster, Doomsayers, 215.

- Paterwic, The A to Z of the Shakers, 245.

- Morton, “Kingdoms in Conflict,” 17.

- Morton, “Kingdoms in Conflict,” 18.

- Pitzer, ed., America’s Communal Utopias, 414.

- Juster, Doomsayers, 216.

- Blumhofer, Restoring the Faith, 45-46.

- Paterwic, The A to Z of the Shakers, 246.

- Morton, “Kingdoms in Conflict,” 22.

- Morton, “Kingdoms in Conflict,” 23.

- Juster, Doomsayers, 217.

- Blumhofer, Restoring the Faith, 47.

- Paterwic, The A to Z of the Shakers, 247.

- Pitzer, ed., America’s Communal Utopias, 418.

- Timothy Miller, America’s Alternative Religions (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995), 332–35.

- Morton, “Kingdoms in Conflict,” 24.

Bibliography

- Blumhofer, Edith L. Restoring the Faith: The Assemblies of God, Pentecostalism, and American Culture. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

- Crowley, John W. Empty Houses: Theatrical Failure and the Novel. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991.

- Juster, Susan. Doomsayers: Anglo-American Prophecy in the Age of Revolution. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003.

- Miller, Timothy. America’s Alternative Religions. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995.

- Morton, Barry. “Kingdoms in Conflict: The Rise and Fall of Frank Sandford’s Shiloh.” Journal of Millennial Studies 2, no. 1 (Spring 1999): 1–25.

- Paterwic, Stephen J. The A to Z of the Shakers. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2009.

- Pitzer, Donald E., ed. America’s Communal Utopias. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.06.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.