The ancient concept of law enforcement was fundamentally different from today.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The maintenance of public order and the enforcement of laws have been essential functions of organized societies in civilized history. In many ancient civilizations, the military—primarily designed for defense and warfare—also played a critical role in law enforcement. This dual role emerged from the need to maintain internal stability, suppress rebellions, protect elite interests, and uphold the authority of rulers in environments where formal police forces either did not exist or were underdeveloped. Here I explore the ancient use of the military in law enforcement across various civilizations, examining the reasons for this overlap, its mechanisms, and its implications for governance and social control.

The Concept of Law Enforcement in the Ancient World

In the ancient world, the concept of law enforcement was fundamentally different from the modern understanding of policing and justice. Unlike today’s specialized police institutions, many ancient societies lacked a formalized or professional law enforcement body dedicated solely to upholding laws and maintaining public order. Instead, the enforcement of laws was often intertwined with the authority of rulers, local elites, religious institutions, and the military. This overlap was partly due to the scale and structure of ancient societies, where centralized bureaucracies were limited, and local governance relied heavily on personal authority and social hierarchies. As a result, law enforcement was as much about maintaining the ruler’s power and social order as it was about administering justice or protecting citizens.1

One core aspect of ancient law enforcement was its strong connection to political authority. Kings, emperors, or city-state rulers were the ultimate source of law and order, often issuing decrees or codes that defined acceptable behavior and punishments for transgressions. These rulers commonly employed military forces or appointed officials who acted as their agents to enforce laws. In many cases, the military played a dual role: defending the territory against external threats and policing the population internally. This militarized approach to law enforcement reflected the precariousness of ancient states, which frequently faced rebellions, banditry, and internal instability. The use of force to maintain social control was not only accepted but expected, as it was seen as essential to preserving the divine or political order.2

Religious institutions also played a crucial role in the enforcement of law in ancient societies. Many early legal codes were intertwined with religious beliefs, and priests or religious officials often acted as judges or enforcers of divine law. For example, in Mesopotamia, laws were presented as decrees from the gods, and temples served as centers of legal authority and social order. Punishments were not merely legal penalties but also carried spiritual consequences. The religious framing of law enforcement reinforced obedience not only to human rulers but also to divine mandates, lending an additional layer of legitimacy and moral authority. This blend of religion and law made law enforcement a sacred duty, with societal order reflecting cosmic harmony.3

Community and family also formed important units of law enforcement in many ancient cultures. In the absence of professional police, local communities took responsibility for policing behavior through social norms, kinship ties, and collective action. This included informal mechanisms such as public shaming, compensation, or feuding to address crimes or disputes. Tribal and clan-based societies often relied on elders or chiefs to adjudicate conflicts and enforce decisions. While these localized systems lacked the centralized power of state-run law enforcement, they were effective in maintaining order within small groups and ensuring social cohesion. However, as societies grew larger and more complex, these community-based enforcement mechanisms became insufficient, prompting rulers to increasingly rely on military or bureaucratic structures to maintain control.4

Law enforcement in the ancient world was a multifaceted and often decentralized process, reflecting the social, political, and religious complexities of early civilizations. It was deeply embedded in the broader functions of power, justice, and social order rather than seen as a distinct profession or institution. The military’s role as an enforcer of laws, the intertwining of religion with legal authority, and the reliance on local communities all shaped how societies regulated behavior and resolved conflicts. Understanding these ancient concepts of law enforcement provides valuable insight into the foundations of modern legal systems and the historical evolution of policing and justice. It reveals how societies have continually adapted their approaches to maintaining order in response to changing social and political realities.5

Military and Law Enforcement in Ancient Mesopotamia

Ancient Mesopotamia, often regarded as the cradle of civilization, developed some of the earliest known legal codes and complex governmental systems. The region’s city-states, such as Ur, Uruk, and Babylon, operated within highly stratified societies where rulers wielded immense power backed by military forces. Law enforcement in Mesopotamia was inseparable from the authority of the king and his military apparatus. The king was not only the political leader but also the chief lawgiver and military commander, whose power was legitimized by divine sanction. This close intertwining of religious authority, law, and military power ensured that law enforcement was a matter of state control, with the military often serving as the king’s instrument to enforce laws, collect taxes, and maintain public order.6

The military in Mesopotamia served both external and internal functions. While legions and conscripted soldiers defended the city-states from invading armies and rival powers, they were also mobilized to suppress internal dissent, banditry, and civil unrest. In many cases, soldiers were stationed at strategic points such as city gates, markets, and temples, functioning as a form of policing force to prevent crimes and uphold the king’s decrees. Military commanders often held judicial authority, enabling them to carry out arrests, detain suspects, and implement punishment. This fusion of military and legal authority reflects the precarious political environment of Mesopotamian city-states, where threats could come not only from outside but also from within the population.7

The famous Code of Hammurabi, dating to around 1754 BCE, codified the laws of Babylon and exemplified how law enforcement was structured within a militarized society. The code prescribed strict punishments for offenses ranging from theft to assault, many of which involved capital or corporal penalties. Enforcement of these laws relied heavily on the authority of the king and his military enforcers. The presence of detailed laws also underscores the state’s effort to assert control over diverse populations by clearly defining offenses and their consequences. Soldiers and officials acted as executors of this legal code, using force when necessary to deter crime and maintain order, illustrating the ancient Mesopotamian principle that law and violence were closely linked in governance.8

Temples and religious institutions further reinforced the connection between law enforcement and divine order in Mesopotamia. Temples were not only centers of worship but also hubs of economic activity and legal administration. Priests and temple officials often collaborated with military authorities to enforce laws, particularly in matters relating to property, commerce, and religious observance. The military’s role extended into protecting temple property and personnel, thereby securing the sacred order alongside the secular legal framework. This blend of the sacred and the secular in law enforcement underscored the belief that maintaining order was both a political necessity and a divine imperative, blurring the lines between civil governance and religious duty.9

Despite the reliance on military power, Mesopotamian law enforcement also incorporated local administrative officials who oversaw daily legal matters. These officials, sometimes drawn from the military ranks or the bureaucracy, acted as judges, tax collectors, and enforcers of royal edicts in provincial towns and villages. Their role was critical in extending the king’s authority beyond the capital cities. However, when local enforcement failed or large-scale disturbances arose, the military was again called upon to restore order. This system of layered authority, combining military power with administrative governance, highlights the complexity of law enforcement in ancient Mesopotamia, where maintaining social order required a delicate balance of force, legal codification, and bureaucratic control.10

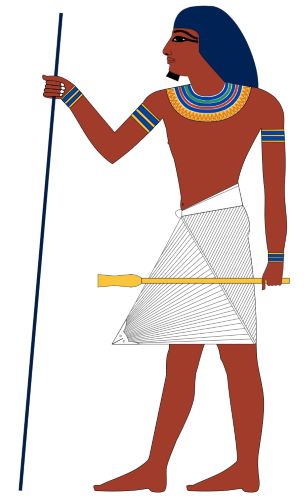

Soldiers as Law Enforcers in Ancient Egypt

In Ancient Egypt, the military was an essential instrument not only in defending the kingdom’s borders but also in maintaining internal law and order. Soldiers were frequently employed as law enforcers, tasked with upholding the pharaoh’s authority throughout the vast territories of the Nile Valley. The Egyptian state was highly centralized, with the pharaoh viewed as both a divine ruler and the ultimate guarantor of maat—the concept of cosmic order, truth, and justice. Soldiers, therefore, did not merely act as warriors but as protectors of this divine order, enforcing laws that ensured stability and harmony within society. Their presence in towns and along key transportation routes was critical to suppressing crime, controlling rebellion, and ensuring compliance with royal decrees.11

The dual role of soldiers as both defenders against external threats and internal law enforcers is evident in Egyptian texts and administrative records. Military garrisons were established not only along border fortifications but also within major cities and strategic locations to serve as deterrents against disorder. Soldiers could arrest criminals, guard prisoners, and execute punishments as authorized by local officials or the pharaoh’s representatives. In some cases, soldiers were directly involved in judicial proceedings, serving as the pharaoh’s agents who enforced verdicts and maintained public security. This militarized approach to law enforcement was vital in a kingdom that spanned diverse ethnic groups and expansive geographic regions, requiring a strong, mobile force to project royal power and law uniformly.12

Pharaohs often emphasized the link between military might and the enforcement of justice in royal propaganda and inscriptions. Kings such as Ramses II portrayed themselves as warriors who crushed chaos and upheld maat through both battlefield victories and domestic governance. Monumental reliefs depict soldiers capturing rebels or criminals, symbolizing the suppression of disorder that threatened the social fabric. The military was thus ideologically intertwined with the legal system and the moral order, serving not only practical functions but also legitimizing the pharaoh’s role as the protector of Egypt’s harmony. This ideological framework reinforced the acceptance of soldiers as rightful enforcers of law and order, blending divine authority with the pragmatic needs of governance.13

Temples and religious institutions also relied on military forces to safeguard their assets and enforce religious law. Temples were economic powerhouses that controlled vast tracts of land, wealth, and labor. Soldiers were often stationed at temple precincts to protect these valuable resources from theft or disruption and to maintain order during religious festivals and ceremonies. Additionally, temples themselves functioned as centers of local governance and justice, with priests acting as judges in many civil and criminal matters. When disputes or disturbances escalated beyond the authority of temple officials, soldiers were called in to restore order, demonstrating the military’s crucial role in supporting both secular and religious law enforcement in Ancient Egypt.14

Despite the reliance on soldiers for enforcement, Ancient Egypt also maintained a complex bureaucratic system that integrated military and civil authority. Officials such as the mayor (haty-a) or nomarch governed provinces and coordinated with military commanders to ensure law enforcement aligned with royal policies. The Egyptian state’s ability to mobilize soldiers quickly across the kingdom allowed it to respond to crises ranging from local insurrections to large-scale rebellions. This coordination between military power and administrative governance exemplifies the sophisticated nature of Ancient Egyptian law enforcement, where soldiers were indispensable agents in maintaining the pharaoh’s peace and justice throughout the land.15

From Hoplites to Urban Policing in Ancient Greece

In Ancient Greece, the concept of law enforcement evolved significantly over time, reflecting the city-states’ shifting political landscapes and social structures. Early Greek warfare relied heavily on the hoplite soldier—a heavily armed infantryman who fought in close formation to defend his polis (city-state). While hoplites were primarily military fighters tasked with defending the polis against external enemies, their role occasionally extended to maintaining internal order, particularly during times of civil unrest or rebellion. However, because the hoplite was a citizen-soldier drawn from the property-owning class, there was limited institutionalization of policing as a separate function. Instead, law enforcement was largely a communal responsibility, tied to citizenship and collective defense.16

As Greek city-states grew more complex, particularly Athens during its classical period, more formal mechanisms for maintaining public order emerged. The Athenians developed a system of urban policing that included specialized groups such as the Scythian Archers, a force employed by the city to enforce laws, execute court orders, and maintain general security. These archers were often non-citizens or slaves, which underscored the growing professionalization and separation of policing from the citizen militia. The Scythian Archers patrolled the streets, guarded public buildings, and supported magistrates in executing their duties. This marked a significant shift from earlier reliance on citizen-soldiers toward a distinct enforcement body focused on internal security.17

The role of law enforcement in Ancient Greece was closely connected to the judicial system and the democratic institutions that characterized some city-states, especially Athens. Magistrates (archons) and other officials were responsible for overseeing legal proceedings and ensuring that verdicts were carried out. However, they did not personally enforce laws; instead, they relied on these specialized police forces or public slaves to execute punishments, arrest suspects, and maintain order. Public participation in legal processes, combined with the delegation of enforcement to designated groups, created a layered approach to law enforcement that balanced citizen oversight with practical enforcement capabilities.18

Beyond Athens, other Greek city-states exhibited varied approaches to policing and law enforcement depending on their political structure. In more oligarchic or monarchic regimes, military forces or appointed officials often fulfilled policing roles, blending military and civil authority. Sparta, for example, relied on a strict military discipline and a system of secret police known as the krypteia to control its large population of helots (serfs) and prevent rebellion. This demonstrates how the militarized enforcement of laws and social order could serve not only to maintain internal security but also to uphold systems of social hierarchy and control.19

Overall, Ancient Greek law enforcement evolved from a citizen-based defense system into more specialized and institutionalized forms, reflecting broader social and political developments. The emergence of urban policing forces like the Scythian Archers and the integration of enforcement with judicial and military institutions highlight the Greek approach to maintaining order within diverse and often fractious city-states. These developments laid important groundwork for later policing systems in the Western tradition, illustrating how ancient societies adapted their methods of law enforcement in response to changing urban realities and political ideologies.20

The Army as Internal Police in Ancient Rome

In Ancient Rome, the army played a critical dual role that extended far beyond the battlefield; it also functioned as a key instrument of internal law enforcement and public order. While the Roman legions were primarily designed for external conquest and defense of the empire’s vast borders, they were frequently called upon to quell civil disturbances, suppress rebellions, and enforce the authority of the state within Roman territories. This internal policing role was especially pronounced during periods of political instability, civil war, or social unrest. The presence of disciplined military forces within urban centers acted as both a deterrent against disorder and a mechanism through which the ruling elite could assert control over increasingly complex and diverse populations.21

Unlike the citizen militias of earlier republics or Greek city-states, the Roman army was a professional, standing force, loyal primarily to its commanders and ultimately to the emperor during the imperial era. This professionalization allowed the military to function effectively as an internal policing body capable of rapid response to riots, conspiracies, or other threats to public security. The urban cohorts (cohortes urbanae) and the Praetorian Guard (cohortes praetoriae), elite units stationed in Rome, were specifically tasked with maintaining public order, guarding important political figures, and enforcing the emperor’s directives. These units operated alongside the vigiles, a more civilian-oriented fire and police force, to create a multi-tiered system of law enforcement where military muscle backed civil authority.22

The Roman army’s involvement in policing also included actions in provincial cities, where legions were often the sole organized force capable of maintaining order. Provincial governors frequently relied on military units to enforce tax collection, suppress banditry, and prevent uprisings among local populations. The blurred line between military and police functions became particularly evident during crises such as the numerous Jewish revolts in Judea or the chaotic Year of the Four Emperors (69 CE), when legions deployed to restore order often operated as agents of state security rather than mere foreign invaders. Such deployments underscored the army’s critical role in sustaining imperial governance through direct enforcement of law and order.23

In addition to forceful interventions, the Roman military’s presence in cities served symbolic and psychological functions. Soldiers marching through urban streets, manning checkpoints, and overseeing public assemblies projected an image of imperial power that reinforced the legal and political status quo. Military discipline, hierarchy, and organization were mirrored in the enforcement of laws, where obedience to authority was paramount. Emperors and magistrates used the army not only to suppress crime but also to intimidate political rivals and prevent sedition, demonstrating how the army as internal police was deeply entwined with the mechanisms of power in Rome.24

However, this reliance on military enforcement came with risks, as soldiers often pursued their own political agendas or were drawn into factional conflicts. Throughout the late Republic and Imperial periods, military commanders with loyal legions could challenge civilian authority, leading to civil wars and usurpations. The very instrument meant to uphold law and order sometimes became a destabilizing force, illustrating the complexities of using an army as internal police. Nevertheless, the integration of military and policing functions was a hallmark of Roman statecraft, reflecting the empire’s pragmatic approach to governance and control over vast and diverse populations.25

Military and Law Enforcement in Ancient China’s Imperial Dynasties

In ancient China, the military and law enforcement functions were closely intertwined under the framework of imperial rule, where maintaining social order and political stability was paramount to the legitimacy of the emperor’s authority. From the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE) onward, the centralization of power led to the establishment of bureaucratic systems designed to control the vast territories and diverse populations of the empire. The imperial military was not only tasked with defending the borders and expanding the empire but also with suppressing internal rebellions, enforcing laws, and supporting local magistrates in maintaining civil order. This blending of military and police roles was essential in a state where legalist principles emphasized strict enforcement and hierarchical control.26

The Qin dynasty’s military reforms laid the foundation for how armies would be utilized in law enforcement in subsequent dynasties. Soldiers were stationed strategically across provinces not only as a deterrent against external invasion but also as a rapid response force against banditry, peasant uprisings, and political dissidents. Imperial officials often relied on military units to implement the harsh legal codes that characterized the Qin legalist system, which demanded strict punishment for infractions to reinforce state authority. This militarized approach to law enforcement persisted in the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), which balanced Confucian ideals with pragmatic governance by using military force as a means to uphold imperial order.27

Law enforcement at the local level involved a complex network of officials, including magistrates and their assistants, who wielded administrative and judicial powers. However, these civil officials often lacked the manpower to enforce laws directly. The imperial military supplemented this gap by providing soldiers who could be called upon to arrest criminals, break up riots, or enforce tax collection. In many cases, the line between soldier and law enforcer was blurred, as garrison troops performed policing duties within cities and rural districts alike. The establishment of the baojia system, a community-based mutual responsibility network introduced during the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE), further integrated civilian and military roles in maintaining local security and public order.28

Throughout imperial history, the military’s involvement in law enforcement was balanced by the development of specialized civil police forces. For example, during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties, the government established the wei and ting systems, which were administrative units responsible for local governance and security. The wei system employed yamen runners and constables, who carried out daily policing functions under magistrates’ supervision. While these constables were civilians, they often coordinated with military units during major disturbances. This dual structure reflected the pragmatic Chinese approach to governance, where civil administration was preferred for routine law enforcement, but military intervention was readily available for crises.29

The symbiotic relationship between the military and law enforcement in ancient China was integral to imperial stability and governance. While the military maintained order and defended the realm from external and internal threats, civil institutions focused on judicial administration and community oversight. This dynamic balance, shaped by changing dynastic policies and philosophies, allowed Chinese rulers to govern effectively over millennia despite frequent social upheavals, rebellions, and invasions. The Chinese experience illustrates the historical complexity of law enforcement as a function embedded within broader political and military systems, combining coercion, bureaucracy, and community responsibility in innovative ways.30

Conclusion

In ancient societies, the military was indispensable not only for defending territories but also for enforcing laws and maintaining public order. The absence of specialized police forces, combined with political centralization and social challenges, made the military the default tool for law enforcement. While this system was effective for maintaining control, it also raised issues related to militarization and the balance between order and justice. The legacy of the ancient military’s role in law enforcement can be traced through history, influencing medieval and early modern governance structures where armies continued to serve dual purposes. Understanding this ancient interplay enriches our perspective on the evolution of policing and civil-military relations in societies worldwide.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Keith Wrightson, Earthly Necessities: Economic Lives in Early Modern Britain (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 15–20.

- Karen Radner, The Trials of Esarhaddon: The Conspiracy of 670 BCE (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 88–90.

- Martha T. Roth, Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1997), 45–47.

- E.P. Thompson, Customs in Common (New York: The New Press, 1991), 55–57.

- David J. Rothman, The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1971), 23–25.

- Marc Van De Mieroop, King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2005), 32–34.

- Harriet Crawford, Sumer and the Sumerians (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 79–81.

- Martha T. Roth, Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor, 98-101.

- Piotr Michalowski, “Religion and Law in Ancient Mesopotamia,” Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions 5, no. 2 (2005): 127–130.

- Jean Bottéro, Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 142–145.

- Toby Wilkinson, The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt (New York: Random House, 2010), 98–100.

- Rosalie David, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 203–205.

- Ian Shaw, Ancient Egypt: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 77–80.

- Richard H. Wilkinson, The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2000), 152–155.

- Donald B. Redford, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, vol. 2 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 230–232.

- Victor Davis Hanson, The Western Way of War: Infantry Battle in Classical Greece (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 45–48.

- Peter Hunt, Ancient Greek and Roman Slavery (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 112–115.

- Moses I. Finley, Democracy Ancient and Modern (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1985), 62–64.

- Paul Cartledge, Sparta and Lakonia: A Regional History 1300–362 BC (London: Routledge, 2002), 256–259.

- Thomas F. Scanlon, Eros and Polis: Desire and Community in Greek Political Theory (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 140–143.

- Adrian Goldsworthy, The Complete Roman Army (London: Thames & Hudson, 2003), 118–122.

- Pat Southern, The Roman Army: A Social and Institutional History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 175–180.

- Fergus Millar, The Roman Near East, 31 BC – AD 337 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), 210–215.

- Mary Beard, SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome (New York: Liveright, 2015), 400–405.

- Harold Whetstone Johnston, The Private Life of the Romans (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1903), 289–295.

- Mark Edward Lewis, The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007), 88–92.

- Li Feng, Bureaucracy and the State in Early China: Governing the Western Zhou (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 134–138.

- Patricia Ebrey, The Cambridge Illustrated History of China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 143–147.

- Frederic Wakeman Jr., The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-Century China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 234–240.

- Philip A. Kuhn, Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990), 89–94.

Bibliography

- Beard, Mary. SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. New York: Liveright, 2015.

- Bottéro, Jean. Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- Cartledge, Paul. Sparta and Lakonia: A Regional History 1300–362 BC. London: Routledge, 2002.

- Crawford, Harriet. Sumer and the Sumerians. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- David, Rosalie. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Ebrey, Patricia. The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Feng, Li. Bureaucracy and the State in Early China: Governing the Western Zhou. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Finley, Moses I. Democracy Ancient and Modern. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1985.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian. The Complete Roman Army. London: Thames & Hudson, 2003.

- Hanson, Victor Davis. The Western Way of War: Infantry Battle in Classical Greece. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

- Hunt, Peter. Ancient Greek and Roman Slavery. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- Johnston, Harold Whetstone. The Private Life of the Romans. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1903.

- Kuhn, Philip A. Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990.

- Lewis, Mark Edward. The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Michalowski, Piotr. “Religion and Law in Ancient Mesopotamia.” Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions 5, no. 2 (2005): 125–140.

- Millar, Fergus. The Roman Near East, 31 BC – AD 337. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

- Radner, Karen. The Trials of Esarhaddon: The Conspiracy of 670 BCE. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

- Redford, Donald B. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Roth, Martha T. Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1997.

- Rothman, David J. The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1971.

- Scanlon, Thomas F. Eros and Polis: Desire and Community in Greek Political Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

- Shaw, Ian. Ancient Egypt: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Southern, Pat. The Roman Army: A Social and Institutional History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Thompson, E.P. Customs in Common. New York: The New Press, 1991.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2005.

- Wakeman Jr., Frederic. The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-Century China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

- Wilkinson, Toby. The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. New York: Random House, 2010.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

- Wrightson, Keith. Earthly Necessities: Economic Lives in Early Modern Britain. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.16.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.