Law enforcement in medieval England was a patchwork of local officials.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Law enforcement in medieval England was a decentralized and community-based system that evolved gradually from early medieval times through the later Middle Ages. Unlike modern professional police forces, medieval law enforcement relied heavily on local officials and ordinary citizens to maintain order, reflecting the social and political structures of the time.

Tenfold Trust: The Power of Tithings

The system of tithings was a fundamental component of community-based law enforcement in medieval England, emerging from Anglo-Saxon traditions and persisting well into the later Middle Ages. A tithing was a group of ten households collectively responsible for each other’s behavior, especially in terms of ensuring that members adhered to the law and appeared in court when summoned. This collective responsibility created a form of mutual surveillance and accountability, wherein the failure of one member to comply with legal demands risked penalties on the entire group. By organizing society in these small units, medieval authorities sought to promote order and reduce crime through communal cooperation rather than through a centralized police force.1

The origins of the tithing system trace back to the early English kingdom’s need for local enforcement mechanisms that could operate in a decentralized society. Without a standing army or professional police, the Anglo-Saxon legal framework depended heavily on local participation in maintaining peace. The term “tithing” itself reflects the numeric organization—ten households grouped together—and its enforcement was closely linked to the concept of the frankpledge, an arrangement where groups pledged to keep the peace and bring offenders to justice. This system was codified in several laws, including those issued by King Alfred the Great and later Norman rulers who retained and adapted these practices after the Conquest.2

Functionally, tithings operated as units of collective suretyship. If one member of the group committed a crime or failed to present himself to the court, the other members were responsible for apprehending the offender or paying fines. This created a strong incentive for members to police each other’s conduct and to discourage antisocial behavior. The mutual accountability of tithings also meant that the community itself played an active role in law enforcement, thereby reducing the burden on sheriffs and other royal officials. The system’s efficiency lay in its ability to harness local social bonds and responsibilities rather than relying solely on external enforcement.3

However, the effectiveness of the tithing system varied depending on the social and political context. In more tightly knit rural communities, tithings could enforce order effectively because social pressure and communal ties were strong. In contrast, in larger or more diverse towns and cities, the system was less practical due to the complexity and anonymity of urban life. Over time, as royal authority increased and more formalized institutions like justices of the peace and paid constables were introduced, the importance of tithings diminished. Yet, the concept of collective responsibility influenced English legal culture long after the medieval period.4

In summary, the tithing system was a key example of communal law enforcement in medieval England, grounded in the principle that neighbors bore mutual responsibility for one another’s conduct. It reflected the decentralized nature of medieval governance and the reliance on local communities to maintain order. While eventually supplanted by more centralized institutions, the legacy of tithings remains an important chapter in the history of English legal development, illustrating the balance between communal obligation and royal authority in medieval society.5

Raise the Alarm: The Hue and Cry as the Original Neighborhood Watch

The hue and cry was a vital legal mechanism in medieval England designed to mobilize the community’s collective responsibility to pursue and apprehend criminals. When a crime was witnessed, the victim or bystanders were expected to raise a loud public outcry—often literally shouting “hue and cry”—to alert nearby residents and summon assistance. This communal call to action obligated all able-bodied men in the vicinity to join the pursuit of the suspect. Failure to respond to the hue and cry could result in fines or penalties, reflecting the system’s importance in maintaining public order in a time before professional police forces existed.6

This practice was rooted in Anglo-Saxon law and was formalized in the legal codes of the period. The principle behind hue and cry was based on the idea that maintaining peace was a shared responsibility among the community, not just the concern of local officials. According to the laws set forth in the Laws of Alfred and later reiterated in the Statute of Winchester (1285), once a hue and cry was raised, all members of the community were legally bound to assist in apprehending the alleged offender.7 This collective obligation extended beyond simple vigilance; it was an active form of community policing that relied on immediate and coordinated action.

The hue and cry was not only a practical tool for catching criminals but also served a symbolic function in reinforcing communal bonds and social order. By requiring neighbors to band together, the practice fostered a sense of mutual responsibility and vigilance that was essential in rural and small-town contexts. However, the system also had limitations, particularly in urban areas where anonymity and population density complicated collective action. Additionally, the efficacy of the hue and cry depended heavily on the community’s willingness and ability to respond, which could be influenced by local allegiances, social hierarchies, or fear of reprisal.8

Legal records from the medieval period indicate that sheriffs and other officials often relied on the hue and cry to supplement their limited resources. The sheriff, responsible for enforcing the king’s peace, had the authority to mobilize the posse comitatus—essentially a temporary militia of local men—to pursue criminals when the hue and cry was initiated. The promptness and volume of the public outcry could greatly affect the chances of capturing a fugitive, demonstrating the practical importance of communal participation in law enforcement during this era.9

Over time, the hue and cry gradually lost its prominence as more formalized policing institutions developed. The establishment of justices of the peace, watchmen, and constables in the late medieval and early modern periods began to professionalize law enforcement. Nevertheless, the hue and cry’s legacy is significant as an early example of community-based policing and legal responsibility. It exemplifies how medieval society balanced individual liberty with communal obligation to uphold justice and social stability.10

The Quiet Power of Medieval England’s Constables

Constables were key figures in the law enforcement system of medieval England, serving as the most local and accessible officers of the law. Their origins can be traced back to the Anglo-Saxon period, where they emerged as officials appointed by local communities or lords to maintain order and enforce legal decisions. Unlike sheriffs, whose authority was county-wide and often more politically charged, constables operated at the parish or village level, making them essential to everyday justice and public safety. They were responsible for tasks such as summoning juries, supervising the watch, and pursuing wrongdoers within their jurisdiction.11

The role of the constable was deeply embedded in the communal and feudal nature of medieval society. Often unpaid or minimally compensated, constables were typically chosen from among respected members of the local population and served for a limited term, sometimes as short as a year. Their duties required balancing the demands of royal justice with the interests of their neighbors, which could be challenging in small communities where personal relationships complicated law enforcement. Nevertheless, constables were expected to uphold the king’s peace by organizing local men for the posse comitatus and ensuring that crimes were reported and punished.12

One of the primary responsibilities of constables was to oversee the night watch, a system where local men patrolled the streets to deter crime and disorder. Constables coordinated these patrols, making sure that watchmen fulfilled their duties and that suspicious activity was reported promptly. This duty was vital in medieval towns and boroughs, where growing populations and increasing commerce brought heightened risks of theft, violence, and disorder. By supervising the watch, constables helped establish a visible presence of authority and contributed to the prevention of crime before it occurred.13

The legal authority of constables expanded significantly following the Statute of Winchester in 1285, which formalized many aspects of local law enforcement. The statute codified the obligation of constables to raise the hue and cry, organize the posse comitatus, and ensure that weapons were kept in check. It also required constables to keep order during local courts and to arrest those suspected of crimes. This legislation marked a critical step toward the professionalization of local law enforcement and underscored the constable’s pivotal role in bridging the gap between royal justice and community enforcement.14

Despite their importance, constables often faced difficulties in carrying out their duties, including resistance from local inhabitants, limited resources, and occasional corruption. The position required a delicate mix of authority, diplomacy, and persistence. Over time, as England’s legal and administrative systems evolved, the constable’s role became more formalized and institutionalized, eventually laying the groundwork for modern policing structures. The legacy of medieval constables remains significant in understanding the development of English law enforcement and community governance.15

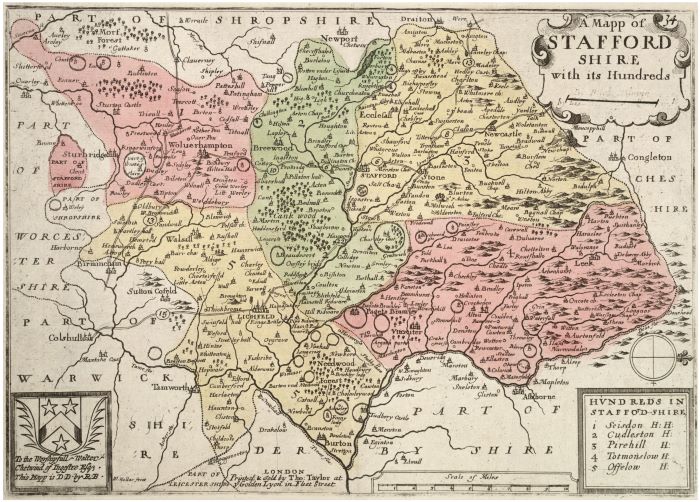

Shire Reeves and Sheriffs: Lawmen before the Badge

The office of the shire reeve, later known as the sheriff, was one of the most significant positions in medieval England’s local government and law enforcement. The term “shire reeve” originates from the Old English “scīrgerēfa,” meaning the royal official responsible for a shire, or county. This official acted as the king’s chief representative at the local level, overseeing the administration of justice, the collection of royal revenues, and the maintenance of law and order. The role was crucial in bridging the gap between the central monarchy and the localities, especially in a period where communication and transportation were limited and royal power depended heavily on delegation.16

Historically, the shire reeve’s duties encompassed a broad spectrum of responsibilities, including convening the shire court, executing writs, supervising the local militia, and collecting taxes and fines owed to the Crown. Unlike constables or tithings, who operated on a more localized or communal level, sheriffs had jurisdiction over the entire shire and wielded considerable power. They were appointed by the king and were often drawn from the local nobility or landed gentry. Their authority, however, was not absolute, as sheriffs were subject to oversight by royal justices and the crown’s bureaucracy, especially after reforms in the 12th and 13th centuries aimed at curbing abuses.17

One of the defining features of the sheriff’s office was its role in law enforcement and criminal justice. Sheriffs were responsible for organizing the posse comitatus—a force of able-bodied men summoned to assist in pursuing and apprehending criminals. They also managed the county jail and were tasked with ensuring that judgments handed down by the king’s courts were carried out. The sheriffs were instrumental in implementing the Statute of Winchester (1285), which formalized many aspects of local law enforcement and required sheriffs to ensure that weapons were kept under control and that the hue and cry was raised when necessary.18

Despite the official powers granted to sheriffs, the office was not without controversy. Sheriffs frequently faced accusations of corruption, abuse of power, and extortion, partly because the position was lucrative and allowed for the collection of fees and fines. The crown occasionally replaced sheriffs who were found guilty of such misconduct, and reforms were introduced to regulate the office more strictly. Nonetheless, the sheriff remained a pivotal figure in medieval English governance, balancing royal authority with local interests and maintaining public order in a period marked by frequent unrest and shifting power dynamics.19

The shire reeve or sheriff was a cornerstone of medieval English administration and law enforcement. The office embodied the delegation of royal authority to the local level and was essential to the functioning of justice, fiscal administration, and security in the counties. While the role evolved over time, its legacy is evident in the continued use of the term “sheriff” in modern English-speaking legal systems and the enduring concept of county-level law enforcement officials representing state authority.20

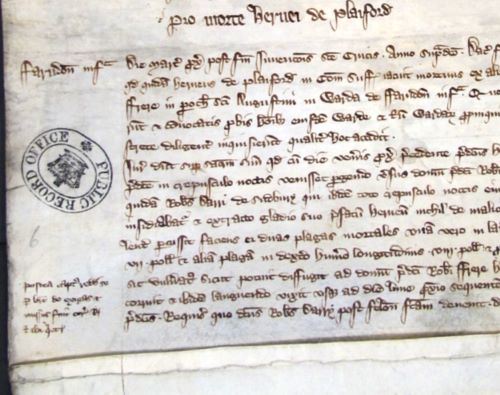

Coroners of the Crown: The First Death Investigators

The office of the coroner in medieval England was established in the late 12th century under the reign of King Richard I, with the primary role of safeguarding the financial interests of the Crown in matters of sudden or suspicious deaths. The coroner, originally called the “crowner,” derived their name from their duty to protect the king’s “crown” or revenue. Unlike modern-day coroners who focus mainly on the investigation of causes of death, medieval coroners had a broader remit, including holding inquests to determine not only the cause of death but also whether fines or forfeitures were due to the Crown as a result of criminal activity or negligence.21

Coroners were royal officers elected in each county and granted significant authority to investigate deaths, particularly those deemed suspicious, violent, or unnatural. They conducted formal inquests with juries to establish facts surrounding deaths and related crimes such as homicide or accidental deaths where negligence was suspected. The coroner’s duties extended beyond death investigations; they were responsible for securing the king’s property rights, including seized goods from criminals, and ensuring the proper administration of justice in cases involving royal interests. This dual role positioned coroners as important figures linking local communities with the royal government.22

The establishment of the coroner’s office reflected the Crown’s growing need to exert control over local jurisdictions, particularly to increase royal revenues and enforce the king’s peace. Before coroners, sheriffs handled many such duties, but concerns over sheriffs’ corruption and inefficiency led to the creation of this separate office. Coroners acted as a check on sheriffs by independently investigating deaths and crimes, thus providing an additional layer of accountability in local governance. Over time, coroners developed distinct procedures, including summoning juries and maintaining records, which contributed to the early development of English common law.23

Medieval coroners frequently faced practical challenges in carrying out their duties. Travel across large rural counties could be difficult, and cooperation from local officials or witnesses was not always forthcoming. The coroner’s success depended heavily on the community’s participation in the inquest process, especially the willingness of jurors to provide truthful testimony under oath. Coroners also had to navigate the complex social hierarchies and local politics of their counties, balancing loyalty to the Crown with relationships in their communities. Despite these challenges, the office persisted and became a fundamental part of England’s legal infrastructure.24

Coroners in medieval England played a critical role at the intersection of law enforcement, judicial inquiry, and fiscal administration. Their establishment enhanced royal authority, improved local accountability, and contributed to the evolution of legal procedures concerning death and crime. Although their functions have evolved significantly since the medieval period, coroners’ origins underscore the historical ties between law, governance, and revenue collection in England’s development as a centralized state.25

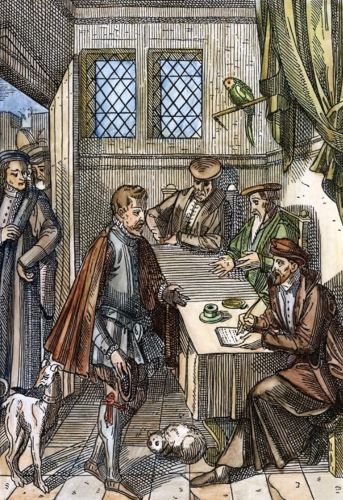

Bailiffs: The King’s Enforcers and Debt Collectors Extraordinaire

Bailiffs in medieval England were important officials responsible for enforcing the legal and economic interests of manorial lords, the Crown, and sometimes ecclesiastical authorities. Originating from the Old French baillif, the role of the bailiff was to act as a manager or overseer of estates and to carry out the lord’s commands in both administrative and judicial matters. Bailiffs were often appointed to oversee the collection of rents, fines, and taxes from tenants, ensuring that dues were paid on time. In this capacity, they were the critical link between the lord’s household and the peasantry, balancing authority and practical management in a feudal economy.26

In their judicial role, bailiffs were frequently involved in manorial courts, where they summoned tenants, maintained order, and sometimes acted as officers executing court judgments. They could be responsible for carrying out evictions, managing distraints (the seizure of goods for unpaid debts), and ensuring compliance with local customs and laws. The bailiff’s authority was limited geographically to the manor or estate they served, but within that jurisdiction, they held considerable power and influence, often acting as the lord’s representative in daily governance.27

The position of bailiff varied widely depending on local customs and the nature of the lord’s holdings. Some bailiffs were full-time, salaried officials, while others were selected from among local free tenants or even peasants who demonstrated administrative aptitude. In some regions, bailiffs played a quasi-police role, organizing the local watch and assisting in the enforcement of law and order alongside constables. They might also oversee agricultural operations, supervise labor services owed by tenants, and manage the lord’s demesne lands directly.28

Bailiffs sometimes encountered tensions in their role due to their position as enforcers of unpopular demands, particularly concerning rent collection and the imposition of fines. This could lead to conflicts with tenants and occasionally local unrest, as bailiffs were viewed as agents of oppression or exploitation by peasants. Despite this, the bailiff’s office was essential to the economic sustainability of medieval estates and the implementation of feudal obligations, making them indispensable figures in rural governance during the Middle Ages.29

Over time, the role of the bailiff evolved with broader legal and administrative changes in England. As royal justice and centralized government expanded, some functions of bailiffs were absorbed or superseded by other officials such as sheriffs or coroners, especially in urban areas. Nevertheless, the bailiff remained a fundamental part of manorial administration well into the late medieval period, embodying the complex relationship between lord, tenant, and the law in England’s feudal society.30

Chief Constables of the Hundred: Local Law Keepers on the Frontline

The office of the Chief Constable of the Hundred played a vital role in the local law enforcement and administration of medieval England. The Hundred was a key administrative division, typically consisting of several villages or parishes, and the Chief Constable was responsible for maintaining order within this jurisdiction. Acting under the authority of the sheriff and the lord of the manor, the Chief Constable organized and led the local constables—often unpaid men drawn from the community—to enforce the law, raise the hue and cry, and gather the posse comitatus when necessary. This position was a crucial link between royal authority and local communities, helping implement justice on a practical, everyday level.31

Chief Constables were typically appointed from among prominent local men who commanded respect and had a degree of social standing. Their duties included overseeing the watch and ward system, ensuring that the community adhered to curfew and other regulations, and dealing with petty crimes and disturbances. Unlike sheriffs, who had county-wide jurisdiction and broader fiscal responsibilities, Chief Constables operated at a more localized level, focusing on the enforcement of law and order within the Hundred. Their role often required balancing community interests with the demands of the Crown and local lords, sometimes placing them in difficult social and political positions.32

One of the most important functions of Chief Constables was their leadership in mobilizing the posse comitatus—a group of able-bodied men summoned to assist in pursuing criminals or suppressing disorder. The Chief Constable was tasked with rallying this force promptly and effectively, a duty that was critical in an era before formalized police forces. They also managed the hue and cry, ensuring that when a crime was committed, the community was alerted and legally obligated to assist in capturing offenders. These responsibilities made Chief Constables central figures in the enforcement of communal justice and the preservation of the king’s peace.33

Despite their important role, Chief Constables often faced challenges in executing their duties. Because they depended on local men who were not professional law enforcement officers, enforcing laws could be inconsistent and subject to local allegiances or conflicts. Furthermore, the position was unpaid and sometimes seen as a burden, leading to difficulties in recruiting capable individuals. Nevertheless, their work was indispensable for maintaining order in the fragmented and decentralized political landscape of medieval England, especially in rural areas far from royal courts.34

Over time, the office of Chief Constable evolved alongside broader changes in English governance and law enforcement. While their specific powers and duties varied across regions and centuries, their role in organizing local law enforcement remained a constant feature of medieval administration. The legacy of the Chief Constable of the Hundred can be seen as a precursor to more centralized and professional police forces in later English history, reflecting the gradual institutionalization of law and order from local communal responsibilities to state-administered policing.35

The King’s Justice: Inside the Royal Courts

The royal courts of medieval England were central institutions for the administration of justice and governance, embodying the authority of the monarch throughout the kingdom. Unlike local manorial courts or hundred courts that dealt with more limited and community-based matters, the royal courts had jurisdiction over a wide range of cases, particularly those involving serious criminal offenses, disputes over land and property, and matters affecting the Crown’s interests. These courts evolved significantly from the Norman Conquest onward, becoming more structured and formalized under successive monarchs, especially during the 12th and 13th centuries.36

One of the most important royal courts was the King’s Bench, which originally traveled with the monarch and dealt with cases concerning breaches of the king’s peace, such as felonies and riots. The King’s Bench had supervisory authority over lower courts and was a key instrument in extending royal justice across England. Another significant court was the Court of Common Pleas, which handled civil disputes between private individuals, often relating to land ownership and contracts. Both courts were staffed by professional judges appointed by the Crown, signaling the increasing professionalization of English law during the medieval period.37

Royal courts operated with elaborate procedures, including the use of writs—formal written orders—to initiate cases. These writs became the foundation of English common law, allowing plaintiffs to bring claims before the king’s judges. The royal courts relied on juries composed of local men to determine facts, particularly in criminal cases and land disputes. This jury system was a vital innovation that contributed to the fairness and consistency of medieval English justice. Moreover, royal courts maintained detailed records, such as plea rolls and court rolls, which have become invaluable sources for modern historians studying medieval legal culture.38

The royal courts also played a significant role in the political and financial affairs of the kingdom. They enforced royal authority by adjudicating cases involving the Crown’s rights and revenues, including disputes over feudal dues, fines, and privileges. By ensuring that justice was administered in the king’s name, these courts reinforced the centralization of power and helped to integrate diverse local customs into a unified legal system. The presence of royal justices across England also promoted stability and deterred lawlessness by providing a consistent forum for dispute resolution.39

Despite their importance, royal courts faced challenges such as delays, costs, and accusations of corruption. Access to royal justice was often limited by geography and expense, prompting the development of alternative legal mechanisms, including local courts and royal commissions. Nonetheless, the legacy of medieval royal courts is profound, as they laid the foundations for the modern English legal system, emphasizing rule of law, centralized judicial authority, and procedural regularity that continued to influence English law for centuries.40

Sanctuary and Salvation: The Church’s Refuge

The concept of sanctuary in medieval England was rooted in a longstanding tradition of offering protection to fugitives within sacred spaces. Churches were considered inviolable under both canon and common law, and those accused of crimes—ranging from theft to homicide—could claim asylum by reaching the altar of a church and invoking the right of sanctuary. This practice reflected the medieval belief that sacred space was immune from secular violence and was overseen by ecclesiastical authorities who often clashed with royal officials over jurisdiction. Sanctuary provided a temporary reprieve from immediate punishment, offering the accused time to seek a more merciful resolution.41

Sanctuary had both practical and spiritual dimensions. A fugitive could remain in sanctuary for up to 40 days, during which time they had to decide whether to stand trial or confess and “abjure the realm”—formally renounce their homeland and go into permanent exile. This process required the individual to swear an oath of abjuration before a coroner and then depart for a designated port, often barefoot and carrying a cross, symbolizing penitence and spiritual rebirth. While sanctuary was not meant to absolve guilt, it was viewed as an opportunity for repentance and divine judgment, rooted in Christian notions of mercy and forgiveness.42

The Church’s power to grant sanctuary was at times a source of tension with the Crown. Monarchs viewed sanctuary as an impediment to their authority and a loophole through which criminals could escape justice. However, kings also recognized its utility in diffusing violent retribution and preserving social order. By allowing sanctuary, the Church acted as a mediator between secular vengeance and spiritual redemption. As a result, sanctuary was both tolerated and regulated. By the 13th century, statutes began limiting sanctuary privileges to certain churches and excluding repeat offenders or those accused of particularly egregious crimes like treason.43

Sanctuary was also subject to abuse and manipulation. Powerful churches and monasteries sometimes protected individuals for political or economic gain, and urban sanctuaries such as Westminster Abbey and St. Martin-le-Grand became notorious for harboring criminals. Some fugitives even used sanctuary strategically, knowing they could confess and opt for exile to avoid execution. This led to increasing pressure from secular rulers to reform or abolish the practice. By the later Middle Ages, the right of sanctuary had become more contentious, viewed by some as undermining royal justice and by others as a necessary counterbalance to harsh legal penalties.44

The decline of sanctuary coincided with the rise of centralized state power and a growing emphasis on uniform legal enforcement. The Tudor monarchs in particular saw sanctuary as an outdated privilege incompatible with their vision of royal supremacy. Henry VII restricted sanctuary rights after using the pretext of abuse to capture political enemies, and Henry VIII dramatically curtailed its use, eventually ending sanctuary for murder and other major crimes. By the early 17th century, the right of sanctuary had been effectively abolished, marking the end of an institution that had, for centuries, offered both hope and controversy in the tangled web of medieval English justice.45

Conclusion

Law enforcement in medieval England was a patchwork of local officials, community obligations, and royal authority. It was characterized by a reliance on communal responsibility and local courts rather than professional policing, laying early groundwork for the later development of the modern justice system.

Appendix

Endnotes

- J. H. Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History, 4th ed. (London: Butterworths, 2002), 45–47.

- Frank M. Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), 328–330.

- G. O. Sayles, The Medieval Foundations of England (London: Methuen, 1966), 102–104.

- H. R. Loyn, The Governance of Anglo-Saxon England, 500–1087 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1984), 145–148.

- Barbara A. Hanawalt, The Ties That Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 78–80.

- Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History, 52-54.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, 332-335.

- Sayles, The Medieval Foundations of England, 108-110.

- Loyn, The Governance of Anglo-Saxon England, 151-153.

- Hanawalt, The Ties That Bound, 82-85.

- Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History, 58-60.

- Sayles, The Medieval Foundations of England, 115-118.

- Hanawalt, The Ties That Bound, 87-90.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, 338-340.

- Loyn, The Governance of Anglo-Saxon England, 158-161.

- Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History, 62-64.

- Sayles, The Medieval Foundations of England, 120-123.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, 342-345.

- Loyn, The Governance of Anglo-Saxon England, 165-168.

- Hanawalt, The Ties That Bound, 90-93.

- Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History, 75-77.

- Sayles, The Medieval Foundations of England, 130-133.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, 350-353.

- Hanawalt, The Ties That Bound, 97-100.

- Loyn, The Governance of Anglo-Saxon England, 172-175.

- Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History, 80-82.

- Sayles, The Medieval Foundations of England, 140-143.

- Hanawalt, The Ties That Bound, 105-108.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, 360-363.

- Loyn, The Governance of Anglo-Saxon England, 180-183.

- Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History, 88-90.

- Sayles, The Medieval Foundations of England, 150-153.

- Hanawalt, The Ties That Bound, 115-118.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, 370-373.

- Loyn, The Governance of Anglo-Saxon England, 185-188.

- Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History, 120-125.

- Sayles, The Medieval Foundations of England, 160-165.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, 385-390.

- Hanawalt, The Ties That Bound, 130-135.

- Loyn, The Governance of Anglo-Saxon England, 195-200.

- Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History, 126-129.

- Karl Shoemaker, Sanctuary and Crime in the Middle Ages, 400–1500 (New York: Fordham University Press, 2011), 93–97.

- R. H. Helmholz, The Oxford History of the Laws of England, Volume I: The Canon Law and Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction from 597 to the 1640s (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 412–417.

- Barbara A. Hanawalt, Crime and Conflict in English Communities, 1300–1348 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979), 75–78.

- Sayles, The Medieval Foundations of England, 175-178.

Bibliography

- Baker, J. H. An Introduction to English Legal History. 4th ed. London: Butterworths, 2002.

- Hanawalt, Barbara A. Crime and Conflict in English Communities, 1300–1348. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979.

- Hanawalt, Barbara A. The Ties That Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Helmholz, R. H. The Oxford History of the Laws of England, Volume I: The Canon Law and Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction from 597 to the 1640s. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Loyn, H. R. The Governance of Anglo-Saxon England, 500–1087. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1984.

- Sayles, G. O. The Medieval Foundations of England. London: Methuen, 1966.

- Shoemaker, Karl. Sanctuary and Crime in the Middle Ages, 400–1500. New York: Fordham University Press, 2011.

- Stenton, Frank M. Anglo-Saxon England. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.16.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.