In a nation historically suspicious of standing armies and centralized power.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The term Posse Comitatus—Latin for “power of the county”—has played a complex and evolving role in American history. Originally a feudal English legal concept referring to the authority of sheriffs to conscript able-bodied men to keep the peace, Posse Comitatus in the American context has undergone significant transformation. Its most prominent contemporary incarnation is the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, which limits the use of the U.S. military in domestic law enforcement. Over the past century and a half, Posse Comitatus has been invoked in legal, political, and even extremist ideological contexts. Here I trace the origins, evolution, and enduring legacy of Posse Comitatus in the United States, exploring its significance in shaping the boundaries between military and civilian power.

Origins of ‘Posse Comitatus’ in Medieval English Common Law

The origins of posse comitatus trace back to early medieval England, where it emerged as a critical legal mechanism embedded within the evolving structure of common law. Rooted in the authority of the local sheriff, the concept provided for the mobilization of able-bodied men to preserve public order and enforce the law when necessary. This authority was not merely discretionary but codified through both customary practice and statutory development. As early as the Assize of Arms in 1181, King Henry II required freemen to maintain arms for defense of the realm and, implicitly, for service in such local levies.1 The sheriff, as the king’s representative in each county, held the right to summon these men—forming a posse—to chase down criminals, quell riots, or ensure the execution of court orders. In this context, posse comitatus was both a practical necessity and a manifestation of royal authority delegated to local actors.

Throughout the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, English monarchs continued to refine and reinforce the concept through statutes aimed at maintaining public order. The Statute of Winchester in 1285, for example, mandated the establishment of a “hue and cry” system whereby citizens were obligated to pursue wrongdoers.2 This communal responsibility directly intersected with the sheriff’s right to call a posse comitatus, highlighting the symbiotic relationship between community obligation and official enforcement. The failure of able-bodied men to respond to such summonses was treated as a serious dereliction of duty, reflecting the importance placed on public participation in law enforcement during a period when no standing police force existed.3 In this sense, posse comitatus was not just a legal tool but also a cultural expectation: law and order were collective enterprises.

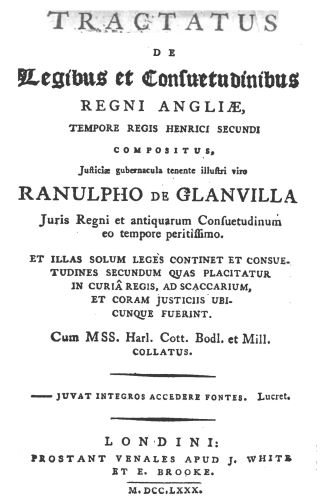

The rise of common law courts and the increasing bureaucratization of royal governance during the late Middle Ages helped formalize the sheriff’s role and his power to summon a posse. Legal treatises such as Bracton’s De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae articulated the rights and responsibilities of sheriffs, reinforcing their central place in both law enforcement and community administration.4 The power of the posse comitatus was understood not as an extraordinary measure but as a routine function of maintaining civil order. This development occurred in tandem with the growing perception of crime and disorder as threats not just to individuals but to the stability of the realm itself. In many respects, the sheriff’s ability to raise a posse was emblematic of medieval England’s hybrid governance model—combining royal prerogative with local enforcement.

Moreover, the use of the posse comitatus helped to blur the line between civil and military authority in medieval society. While the posse was composed of civilians, its organization and function bore striking similarities to military levies. In times of unrest, such as during the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, sheriffs and justices of the peace could employ the posse to protect property and suppress rebellion, effectively militarizing local civil society.5 Yet the legitimacy of the posse comitatus derived not from martial prowess but from its roots in the common law tradition and its endorsement by statutory authority. This dual identity—simultaneously a civic obligation and a coercive force—illustrates the complexities inherent in medieval governance, where power was both dispersed and hierarchical.

By the early modern period, the concept of posse comitatus had become deeply embedded in English legal consciousness. It was referenced in legal commentaries such as Sir Edward Coke’s Institutes of the Lawes of England, which affirmed the sheriff’s right to call upon the community in the service of the king’s peace.6 This enduring tradition would eventually cross the Atlantic with English colonists, who brought with them not only common law principles but also institutional expectations regarding the relationship between authority and public participation in law enforcement. Thus, the medieval origins of posse comitatus would continue to exert influence in the development of American legal thought and practice well into the modern era.

‘Posse Comitatus’ in Colonial and Early America

In Colonial America, the English tradition of posse comitatus was not only retained but became a vital part of early law enforcement infrastructure in a society with minimal formal policing. Sheriffs in colonial counties wielded broad powers similar to their English counterparts, including the ability to summon the posse comitatus—able-bodied male citizens over the age of fifteen—to aid in arresting fugitives, suppressing riots, and executing writs. This communal approach to policing was not merely pragmatic but also ideological, reflecting the colonial belief in civic duty and participatory governance. The concept was deeply embedded in statutes across the colonies, such as the Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641) and the Virginia Laws of 1662, which codified public responsibility in maintaining law and order.7 In frontier regions especially, where the thin presence of formal authority rendered sheriffs highly dependent on local assistance, the posse became an indispensable tool for civil enforcement.

The necessity of the posse comitatus in the colonies was heightened by the volatility of early American society, characterized by geographic dispersion, conflicts with Indigenous peoples, and limited military protection. The decentralized nature of colonial governance meant that sheriffs often stood as the only agents of law enforcement across vast territories. When pursuing escaped indentured servants, capturing accused criminals, or enforcing judicial decisions, sheriffs called on citizens to serve in the posse as a civic obligation akin to jury duty or militia service.8 Failure to respond could result in fines or imprisonment, demonstrating the seriousness with which colonial authorities regarded the practice. Furthermore, the role of the posse in public life reflected the broader republican ethos of shared responsibility—a notion that would later underpin Revolutionary thought and the framing of American civil institutions.9

While the posse comitatus was grounded in civil authority, it sometimes operated in a gray area between civilian and military power, particularly in instances of large-scale disorder. During episodes such as Bacon’s Rebellion (1676) or the Stamp Act protests in the 1760s, colonial sheriffs and governors occasionally attempted to use posse power to restore order, often with mixed results. The reliance on a posse in these moments exposed both the strengths and limitations of decentralized law enforcement. In some cases, members of the community were unwilling to suppress movements they sympathized with, rendering the posse ineffective.10 These failures underscored the need for more formalized policing systems, a trend that began to emerge in the 18th century but would not come to full fruition until the 19th. Nevertheless, the posse continued to function as a key mechanism through which authority was asserted in colonial and early national settings.

After the American Revolution, the concept of posse comitatus remained a fixture of the legal and civic landscape, reinforced by the new nation’s aversion to standing armies and centralized executive power. The early republic saw the continuation of this tradition in local and state laws, which preserved the sheriff’s authority to raise a posse as a defense against tyranny and lawlessness. This was particularly evident in the Whiskey Rebellion of the 1790s, where federal and state officials initially attempted to use civil means—including posse comitatus—to quell tax resistance before ultimately resorting to federal troops under President George Washington’s command.11 The reluctance to involve the military reflected a deeply held belief in the supremacy of civil authority—a principle rooted in English law and transplanted into the American legal consciousness. The reliance on posse comitatus in these early moments of federal crisis reflected not only practical concerns but also philosophical commitments to republican governance.

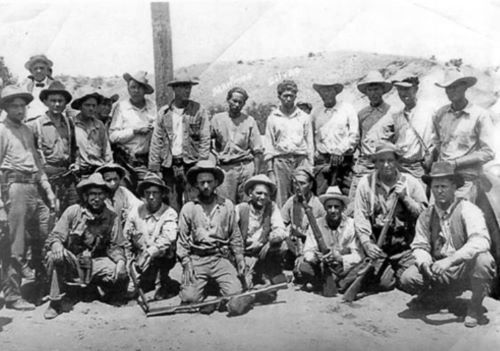

As the United States expanded westward during the early 19th century, the use of the posse comitatus persisted in frontier justice systems, becoming an icon of American legal culture. Popular representations of the sheriff and his posse in Western folklore and literature helped mythologize the institution, casting it as a symbol of localized justice and community vigilance.12 Yet beneath the myth lay a complex reality. The posse was frequently used not only for legitimate law enforcement but also to enforce racial hierarchies and suppress resistance by enslaved people, Indigenous groups, or marginalized communities. While it retained its legal basis and democratic aura, posse comitatus was also a tool of coercion and exclusion. Its legacy in Colonial and Early America thus reveals the dual nature of communal enforcement—at once a practice of civic solidarity and a potential instrument of oppression.

Civil War and Reconstruction: Shifting Boundaries

The Civil War marked a major turning point in the interpretation and application of posse comitatus in the United States, as the boundaries between civil and military authority became increasingly blurred. Prior to the war, the use of posse comitatus remained largely a local matter, with sheriffs relying on citizens to enforce the law and maintain public order. However, the national crisis of secession forced the federal government to assert new forms of authority, particularly through military means. President Abraham Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus and deployment of federal troops within the Union and border states raised concerns among civil libertarians about the encroachment of military power into civilian life.13 While posse comitatus traditionally symbolized local, civilian enforcement, the exigencies of war introduced a new model: the use of military personnel for civil governance in occupied Confederate territories, effectively supplanting the sheriff’s posse with armed soldiers acting under executive authority.14

During Reconstruction, the conflict over civil versus military jurisdiction intensified, particularly in the former Confederate states. Federal troops were stationed throughout the South to enforce civil rights laws, protect freedpeople, and support the Reconstruction governments established by Congress. The presence of these troops—often performing duties historically assigned to civilian law enforcement—sparked political backlash, especially among white Southern Democrats who viewed this intervention as both unconstitutional and oppressive. In this context, posse comitatus became a rhetorical and legal battleground. Radical Republicans argued that federal enforcement was essential to protect the rights of newly freed African Americans, especially in areas where local sheriffs and posses were complicit in racial violence or unwilling to uphold federal law.15 Conversely, Southern elites framed the use of federal troops as a violation of local sovereignty and an overreach of federal power—effectively a military occupation under the guise of civil administration.

The rise of the Ku Klux Klan and other paramilitary groups during Reconstruction further complicated the legal landscape. These organizations often mimicked or usurped the role of the posse comitatus, claiming to act in defense of local order while in reality terrorizing freedpeople and undermining Reconstruction governments. In response, Congress passed the Enforcement Acts between 1870 and 1871, which allowed the president to use federal troops and marshals to suppress insurrection and enforce civil rights.16 The acts implicitly challenged traditional notions of posse comitatus by elevating federal military enforcement over local, citizen-based enforcement systems. At the same time, they reflected a broader shift in legal thinking: that the state’s monopoly on legitimate violence could no longer be trusted to local actors in regions where law and justice were racially and politically compromised.

The culmination of this transformation came in 1878 with the passage of the Posse Comitatus Act, which, paradoxically, restricted the use of the military in civil law enforcement—a direct reaction to the perceived abuses of federal power during Reconstruction. Sponsored by Democratic Congressman J. Proctor Knott of Kentucky, the act prohibited the use of the Army (and later the Air Force) to execute domestic laws unless expressly authorized by Congress.17 This legislation formalized a key shift in American legal doctrine: while posse comitatus had once signified the obligation of civilians to enforce the law under a sheriff’s command, it now came to represent the boundary line between military and civilian spheres of governance. The Act thus embodied a post-Reconstruction consensus that sought to restore traditional federalism and limit centralized authority—especially the presence of federal troops in local jurisdictions.

Yet even as the 1878 Act constrained military involvement in civil affairs, it did not abolish the principle of posse comitatus itself. Sheriffs and U.S. Marshals retained the right to summon private citizens to form a posse, and the federal government could still authorize military involvement under specific conditions, such as enforcing federal court orders or suppressing insurrection.18 The real change lay in the redefinition of posse comitatus from a broad civic duty rooted in common law to a narrowly construed legal doctrine governing the limits of federal power. In the aftermath of the Civil War and Reconstruction, posse comitatus no longer stood primarily for communal participation in local justice. Instead, it became a symbol—invoked both in legal texts and political rhetoric—for the protection of civil society from military interference. This transformation would continue to influence debates about federalism, civil liberties, and the militarization of law enforcement into the twentieth century and beyond.

The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878

The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 (PCA) emerged from the ashes of Reconstruction as a legislative attempt to limit federal military involvement in domestic law enforcement and restore a balance between civil and military authority. Passed as an amendment to the Army Appropriations Bill, the Act was championed by Southern Democrats who were eager to prevent further federal intervention in Southern political and racial affairs. Its original language prohibited the use of the Army to “execute the laws” of the United States within its borders unless expressly authorized by the Constitution or an act of Congress.19 While the Act did not outlaw the use of federal troops in every civil context, it symbolized a turning point in American federalism—one that marked a retreat from the strong federal presence that had characterized Reconstruction. The legislation was intended to curtail the executive branch’s capacity to unilaterally deploy troops for civilian law enforcement and to restore local control, particularly in the former Confederate states.

The Act’s passage was driven by political fatigue with the militarization of Southern life during Reconstruction and by growing fears of federal overreach. For over a decade, federal troops had served not only to enforce civil rights laws but also to suppress resistance to Reconstruction governments. The disputed presidential election of 1876 and the subsequent Compromise of 1877—through which Rutherford B. Hayes secured the presidency in exchange for the withdrawal of remaining federal troops from the South—created the political context in which the Posse Comitatus Act could be passed with bipartisan support.20 For Southern Democrats, the Act represented a legislative capstone to their broader campaign of “Redemption,” aimed at ending Reconstruction and reasserting white supremacy. For many Northern Republicans, it was an acceptable concession in the interest of national reconciliation, even as it effectively signaled the federal government’s abandonment of its commitment to Black civil rights.

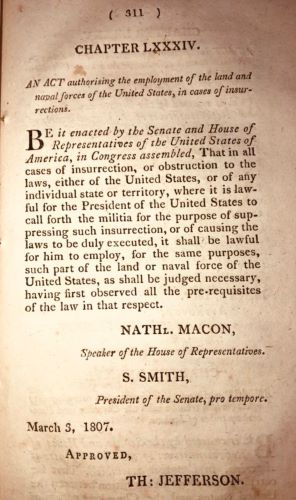

Although often viewed as a categorical prohibition, the PCA included significant exceptions that left open avenues for military participation in civil affairs. The most important caveat was that Congress could still authorize military involvement explicitly through legislation. Moreover, the Act initially applied only to the Army; it would not be extended to the Air Force until 1956, and it has never formally covered the Navy or Marine Corps, although Department of Defense policy voluntarily applies its restrictions to all branches.21 Further, the president retained constitutional authority to invoke the Insurrection Act of 1807, which permits the use of military force in cases of rebellion, obstruction of justice, or civil disorder.22 These exceptions demonstrate that while the Act was a powerful symbolic affirmation of civil primacy, it was not a blanket prohibition but rather a procedural constraint requiring legislative authorization for military deployment in domestic law enforcement.

Legal interpretations of the PCA have evolved over time, particularly in response to emergencies such as labor unrest, natural disasters, and civil rights protests. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, federal troops were deployed on several occasions to suppress strikes and riots, often under congressional or presidential authority, raising ongoing questions about the scope and enforceability of the Act. In United States v. Red Feather (1975), a federal court emphasized that the Act was not violated when military forces provided logistical support or training to law enforcement, as long as they did not directly engage in civilian policing.23 This and other rulings have clarified that the Act restricts “direct active participation” in law enforcement but allows for supportive roles. Thus, the Act has been interpreted not as an absolute wall but as a filter—designed to limit, but not eliminate, military involvement in domestic affairs.

Despite its historical roots, the PCA remains a central reference point in contemporary debates over militarization, homeland security, and the balance of civil liberties. The post-9/11 era, in particular, has witnessed renewed scrutiny of the Act, as the federal government has expanded domestic surveillance and counterterrorism programs that sometimes blur the lines between military and police functions.24 While Congress and courts have generally upheld the Act’s restrictions, various administrations have sought ways to adapt or work around them, especially through the National Guard (which is not bound by the Act when operating under state authority). The ongoing tension between national security imperatives and civil liberties ensures that the PCA remains not only a historical artifact of the Reconstruction era but also a living legal doctrine with profound implications for American governance.

Exceptions, Ambiguities, and Evolving Interpretations

Overview

Despite its clear intent, the PCA is not absolute. Over time, numerous exceptions and qualifications have developed.

National Guard and State Militias

One of the most significant complexities of the 1878 Posse Comitatus Act lies in its exceptions and the evolving interpretations regarding the role of the National Guard and state militias. Although the Act restricts the use of the U.S. Army—and later, the Air Force—from participating in domestic law enforcement without explicit congressional authorization, it does not apply to the National Guard when it is under state authority (Title 32) or to state militias, which remain under the command of governors.25 This legal distinction has allowed governors to deploy the Guard during emergencies—such as natural disasters, civil unrest, or public health crises—without violating federal restrictions. However, once federalized under Title 10, the National Guard becomes subject to the Act, and its use in law enforcement roles becomes constrained by the same legal boundaries that apply to active-duty forces.²⁶ These dual statuses introduce a layer of ambiguity that has led to considerable debate over where military support ends and law enforcement begins. For instance, during Hurricane Katrina, Guard troops operated in both state and federal roles, raising questions about command structures and legal authority.²⁷ Similarly, the deployment of National Guard troops to Washington, D.C., during the January 6 Capitol riot response in 2021 prompted scrutiny over the limits of executive power and the invocation of the Insurrection Act.²⁸ Courts and legal scholars have generally upheld a flexible interpretation that allows military logistical support—such as intelligence sharing, transportation, and crowd control equipment—as long as direct participation in arrests or searches is avoided.²⁹ These evolving interpretations reflect broader tensions between public safety needs, the constitutional separation of powers, and the preservation of civil liberties in the face of national emergencies

Insurrection Act (1807)

The PCA, while establishing a strong legal boundary between civilian and military jurisdictions, contains several critical exceptions and ambiguities—particularly in its relationship with the Insurrection Act of 1807—that have allowed for evolving interpretations over time. The Insurrection Act serves as the most prominent statutory exception to the PCA, permitting the president to deploy military forces domestically to suppress rebellion, insurrection, or civil disorder when state authorities are unable or unwilling to maintain public order.30 This Act, invoked during historical crises such as the 1957 Little Rock desegregation and the 1992 Los Angeles riots, allows military involvement in civil affairs without violating the PCA.31 However, its vague language and broad grant of presidential discretion have raised alarms among legal scholars and civil libertarians, particularly in the post-9/11 era and during periods of political unrest.32 Compounding the ambiguity is the fact that the PCA never defined what constitutes “executing the laws,” leading courts to interpret the statute narrowly, permitting indirect military support like logistics or surveillance while prohibiting direct participation in arrests, searches, or evidence collection.33 Moreover, the PCA does not apply to state National Guard units operating under a governor’s command (Title 32), nor to military forces acting under express congressional authorization, creating multiple pathways for federal or quasi-military intervention that can bypass PCA constraints.34 These interpretive gaps have led to increased calls for reform, especially in light of controversial military deployments during domestic protests and emergencies, highlighting the urgent need to clarify the legal boundaries between military power and civil authority in modern American governance.35

Military Support Roles

Though the PCA restricts direct military involvement in civilian law enforcement, numerous exceptions, ambiguities, and evolving interpretations have allowed a wide range of military support roles to persist under its framework. The Act specifically prohibits active-duty Army and Air Force personnel from “executing the laws” unless expressly authorized by the Constitution or Congress, but it does not clearly define what constitutes execution, leading courts and policymakers to draw a crucial distinction between direct and indirect involvement.36 As a result, military personnel have routinely provided support functions—such as logistical assistance, transportation, training, intelligence-sharing, surveillance, and the loaning of equipment—without being considered in violation of the PCA.37 For example, during counterdrug operations, the Department of Defense has long provided equipment and training to civilian agencies under statutes like the Defense Authorization Act, which Congress has used to carve out specific exceptions to PCA restrictions.38 Moreover, evolving doctrines such as “military assistance to civil authorities” (MACA) and “military assistance for civil disturbances” (MACDIS) allow for a wide spectrum of activity, provided that military personnel do not perform arrests, searches, or direct enforcement actions.39 These practices have drawn scrutiny in contexts such as the 1992 Los Angeles riots, post-9/11 homeland security operations, and more recently, federal responses to civil unrest during protests in 2020, all of which pushed the boundaries of what indirect military involvement might entail.40 Critics argue that these blurred lines can effectively circumvent the spirit of the PCA by enabling military influence in civilian affairs under the guise of support, raising ongoing concerns about the militarization of domestic policing and the erosion of civil-military boundaries.41

War on Drugs and Homeland Security

The PCA has faced substantial reinterpretation and redefinition since the 1980s, particularly during the War on Drugs and the post-9/11 expansion of Homeland Security operations, both of which have significantly blurred the boundaries between military and law enforcement roles.42 In response to rising drug-related violence, Congress enacted statutory exceptions throughout the 1980s, including provisions in the 1981 Military Cooperation with Civilian Law Enforcement Agencies Act, which authorized the Department of Defense to share intelligence, loan equipment, and train civilian agencies for drug interdiction.43 These exceptions enabled military entities, particularly the National Guard under state authority, to participate actively in counternarcotics missions while technically remaining within the PCA’s legal framework.44 The trend accelerated after 9/11, when homeland security initiatives further expanded military-civilian cooperation under the umbrella of national defense. The establishment of U.S. Northern Command (USNORTHCOM) in 2002 institutionalized the military’s domestic support role, and legislative tools like the USA PATRIOT Act and the Homeland Security Act of 2002 facilitated broader surveillance, intelligence sharing, and operational coordination between federal military and civilian law enforcement agencies.45 While direct military involvement in arrests or searches remained restricted, these evolving legal interpretations allowed the military to engage deeply in domestic operations that would have previously raised concerns under the PCA.46 Critics argue that this expansion—often justified by crises—has undermined the core principle of civilian supremacy and eroded constitutional protections by militarizing domestic policing through proxy and support roles.47 As a result, the PCA’s limitations have become increasingly porous, functioning more as a symbolic barrier than a practical restraint in the modern security landscape.

The Posse Comitatus Movement and Far-Right Extremism

The Posse Comitatus Movement (PCM) emerged in the United States during the late 1960s and early 1970s as a loosely organized far-right extremist ideology rooted in anti-government sentiment, white supremacy, and a rejection of federal authority.48 Drawing symbolic inspiration from the historic posse comitatus principle of local citizen militias assisting law enforcement, the movement co-opted the term to promote the idea that the “county sheriff” was the ultimate lawful authority within American jurisdiction, rather than federal officials or agencies.49 Adherents of the movement asserted that federal laws and taxes were illegitimate, often refusing to recognize the authority of federal courts, the IRS, and other government institutions.50 This radical rejection of federal authority was intertwined with conspiracy theories about the government’s overreach and perceived encroachments on individual freedoms, particularly those of white, rural Americans. The Posse Comitatus Movement was heavily influenced by earlier tax protest and sovereign citizen ideas, but it fused these with explicit racial and anti-Semitic rhetoric, frequently blaming Jewish financiers and federal agents for societal problems.51 The movement’s violent fringe engaged in armed standoffs, intimidation of public officials, and various forms of fraud and domestic terrorism, setting the stage for later far-right militancy in the U.S.

The legal and cultural underpinnings of the PCM drew selectively on obscure interpretations of American and English common law, often misunderstanding or deliberately misapplying the historical posse comitatus concept as a basis for their anti-government claims.52 Posse members believed that county sheriffs had sovereign power to nullify federal laws and protect citizens from government tyranny, a claim that courts consistently rejected.53 The movement’s anti-tax stance led to widespread confrontations with law enforcement and tax authorities, culminating in arrests, prosecutions, and sometimes violent resistance.54 This confrontational posture contributed to the movement’s classification by the FBI as a domestic extremist threat by the late 1970s.55 The movement’s ideology overlapped with militia and survivalist groups that proliferated in the 1980s and 1990s, as economic uncertainties and cultural anxieties fueled broader distrust in government institutions.56 Additionally, Posse Comitatus adherents were involved in early “sovereign citizen” activities, including filing frivolous liens, bogus legal documents, and bogus citizenship claims to obstruct legal processes.57

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the PCM waned in public visibility but left a lasting imprint on the far-right extremist landscape.58 Its core ideas diffused into a patchwork of related groups and individuals who continued to espouse anti-government, anti-tax, and racist ideologies.59 Some Posse affiliates were implicated in violent acts, including bombings, bank robberies, and assassinations of government officials, highlighting the dangerous potential of this extremist ideology.60 Moreover, Posse Comitatus principles inspired a resurgence of militia movements during the 1990s, notably during events such as the Ruby Ridge standoff (1992) and the Waco siege (1993), which further polarized public debate over government authority and individual rights.61 The Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, perpetrated by Timothy McVeigh, a militia sympathizer, echoed many themes championed by the Posse Comitatus Movement, underscoring the lethal consequences of its extremist rhetoric.62 Despite law enforcement efforts to dismantle these networks, the movement’s ideas persisted underground and later found new expression through online platforms.

In the 21st century, the PCM’s ideology has intertwined with broader far-right extremism, including sovereign citizen movements, anti-government militias, and white supremacist groups.63 The growth of the internet and social media has allowed adherents to disseminate their doctrines widely, recruit new members, and coordinate actions more effectively.64 Many sovereign citizen tactics—such as filing fraudulent liens and asserting immunity from law enforcement—trace their roots to Posse Comitatus ideology.65 Post-9/11 security measures and economic recessions have further fueled resentment among far-right activists, who perceive the federal government as oppressive and illegitimate.66 The FBI continues to monitor Posse Comitatus adherents as part of its domestic terrorism and counter-extremism efforts, recognizing the ongoing threat posed by their anti-government violence and conspiracy-driven worldview.67 Events such as the 2014 Bundy standoff in Nevada and the 2021 January 6 Capitol riot featured participants sympathetic to Posse Comitatus ideas, demonstrating the movement’s enduring influence in contemporary political violence.68

The legacy of the PCM raises profound challenges for law enforcement, policymakers, and civil society in addressing domestic extremism without infringing on constitutional rights.69 Efforts to counter the movement’s influence have included targeted investigations, prosecutions for violent crimes, public education campaigns about sovereign citizen fraud, and community engagement initiatives.70 Scholars argue that understanding the historical origins and ideological evolution of Posse Comitatus extremism is crucial for developing effective countermeasures that address the movement’s root causes—namely, deep-seated grievances about government legitimacy, racial and economic anxiety, and identity politics.71 At the same time, civil liberties advocates caution against overly broad surveillance or suppression measures that could infringe on lawful dissent or free speech.72 The persistence of Posse Comitatus-inspired ideas in the broader constellation of far-right extremism underscores the importance of nuanced, multifaceted approaches that combine legal, social, and educational strategies to safeguard democratic institutions while protecting fundamental rights.

Contemporary Relevance and Debate

The PCA remains a cornerstone of American legal doctrine limiting the domestic use of the U.S. military in civilian law enforcement.73 Yet, its relevance and application have been the subject of vigorous debate, particularly in the context of modern national security challenges and evolving definitions of “military” and “law enforcement.”74 Critics argue that the PCA’s original intent—to prevent federal military overreach and protect civilian sovereignty—faces unprecedented tests in an era marked by terrorism, cyber threats, and complex transnational crime.75 Supporters contend that the Act continues to provide an essential constitutional safeguard against militarization of domestic policing, preserving civil liberties and the separation of powers.76 The rise of unconventional threats, such as violent extremism and large-scale civil unrest, has prompted renewed scrutiny over how and when the military can be deployed on U.S. soil, exposing tensions between national security imperatives and constitutional protections.

One key point of contention is the broad array of statutory exceptions and interpretations that have evolved around the PCA, which some argue have effectively eroded its original restrictions.77 For instance, the National Guard, when activated by state governors, operates under state authority and is exempt from the PCA, allowing it to engage in law enforcement activities.78 Additionally, the Insurrection Act provides a legal mechanism for the president to deploy active-duty military forces domestically under certain circumstances, such as insurrection, rebellion, or when states request assistance.79 The increasing use of military assets in support roles—such as intelligence sharing, training, and logistics—further blurs the line between civilian law enforcement and military involvement.80 This ambiguity has led to calls for legislative clarity to better define permissible activities and avoid potential abuses or misunderstandings that could jeopardize civil liberties.81

The PCA’s contemporary relevance has been thrust into the spotlight during high-profile incidents involving domestic unrest, including the 1992 Los Angeles riots, the 2014 Bundy standoff, and the widespread protests following the killing of George Floyd in 2020.82 In these situations, the potential or actual deployment of federal troops raised significant public debate over the proper balance between maintaining order and respecting citizens’ rights to protest and assemble.83 The military’s role in these events often involved support to civilian law enforcement agencies rather than direct enforcement, highlighting the practical challenges in maintaining PCA compliance while addressing urgent security needs.84 The political polarization surrounding these incidents also fueled concerns about the military being used as a tool for political ends, exacerbating mistrust between government institutions and segments of the public.85 Consequently, the PCA functions not only as a legal boundary but as a symbol of democratic restraint and the principle of civilian control.

Legal scholars and policymakers have debated potential reforms to the PCA to reflect contemporary realities without undermining its fundamental protections.86 Some propose clearer statutory language to delineate the scope of permissible military support roles, aiming to reduce confusion and provide operational guidance to commanders and law enforcement officials.87 Others advocate for reinforcing the PCA’s restrictions to prevent incremental militarization of domestic policing, especially amid growing concerns about the militarization of police forces and use of military-grade equipment in local law enforcement.88 The challenges of cyber and information warfare also pose questions about how the military can lawfully support civilian agencies in non-traditional domains, such as cybersecurity defense and counterterrorism intelligence.89 Any reform efforts must balance effective security responses with preserving constitutional protections against military intrusion into civilian affairs.90

Ultimately, the Posse Comitatus Act continues to be a critical legal and cultural touchstone in the United States, symbolizing the nation’s commitment to civilian supremacy and the rule of law.91 Its ongoing relevance hinges on careful navigation of the evolving security landscape, democratic norms, and public trust in institutions.92 As the country confronts new and complex threats, the PCA remains a vital framework for ensuring that the military’s extraordinary power is exercised with restraint and accountability within the homeland.93 Robust public dialogue, transparent policymaking, and informed legal interpretation will be essential in maintaining the delicate balance that the PCA embodies—between safeguarding national security and protecting individual freedoms in a democratic society.94

Conclusion

The history of Posse Comitatus in the United States is one of legal boundaries, political anxieties, and evolving interpretations. From its roots in English law to its formal codification in 1878, and its contested role in modern governance and ideology, Posse Comitatus encapsulates America’s uneasy balance between liberty and security, civilian authority and military power. In a nation historically suspicious of standing armies and centralized power, the Posse Comitatus Act serves as both a safeguard and a symbol—a reminder of the delicate line between enforcement and enforcement by force, and of the enduring tension at the heart of democratic governance.

Appendix

Endnotes

- William Stubbs, Select Charters and Other Illustrations of English Constitutional History (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1900), 222.

- Henry Summerson, “Law and Order in the Medieval English Town: The Use of the ‘Hue and Cry’,” The English Historical Review 103, no. 407 (1988): 583–605.

- John Hudson, The Formation of the English Common Law: Law and Society in England from the Norman Conquest to Magna Carta (London: Routledge, 1996), 123–25.

- Henry de Bracton, On the Laws and Customs of England, trans. Samuel Thorne (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1968), 435–37.

- R.B. Dobson, The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 (London: Macmillan, 1970), 184–86.

- Sir Edward Coke, The Second Part of the Institutes of the Lawes of England (London: 1642), 52–53.

- William H. Nelson, The Common Law in Colonial America, vol. 1 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 57–60.

- Christopher Tomlins, Law, Labor, and Ideology in the Early American Republic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 71–72.

- Mary Sarah Bilder, The Transatlantic Constitution: Colonial Legal Culture and the Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 102–104.

- Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (New York: W.W. Norton, 1975), 276–79.

- Saul Cornell, The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788–1828 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 150–51.

- Richard Maxwell Brown, No Duty to Retreat: Violence and Values in American History and Society (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991), 94–96.

- Mark E. Neely Jr., The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 78–82.

- James G. Randall, Constitutional Problems under Lincoln (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1951), 130–34.

- Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 443–45.

- William Gillette, Retreat from Reconstruction, 1869–1879 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979), 113–16.

- Charles Doyle, The Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters: The Use of the Military to Execute Civilian Law (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2012), 3–4.

- Matthew C. Waxman, “Military Power and the Posse Comitatus Act,” Journal of National Security Law & Policy 2, no. 2 (2008): 295–310.

- Stephen I. Vladeck, “The Posse Comitatus Act Explained,” Texas Law Review 93, no. 5 (2015): 1171–1173.

- Heather Cox Richardson, The Death of Reconstruction: Race, Labor, and Politics in the Post-Civil War North, 1865–1901 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 212–14.

- Doyle, The Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters, 5-6.

- Jennifer K. Elsea, The Insurrection Act and Related Authorities: Background and Legislative Issues, Congressional Research Service Report R42659 (Washington, DC: CRS, 2020), 1–3.

- United States v. Red Feather, 392 F. Supp. 916 (D.S.D. 1975).

- Matthew C. Waxman, “The Use of Military Force in Homeland Defense: Law and Policy,” Columbia Journal of Transnational Law 43, no. 2 (2005): 438–41.

- Doyle, The Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters, 6-8.

- Elsea, The Insurrection Act and Related Authorities, 5-6.

- Matt Matthews, The Posse Comitatus Act and the United States Army: A Historical Perspective (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2006), 79–82.

- Stephen I. Vladeck, “The National Guard, the Posse Comitatus Act, and the January 6 Insurrection,” Lawfare, January 10, 2021.

- Waxman, “Military Power and the Posse Comitatus Act,” 301-303.

- Elsea, The Insurrection Act and Related Authorities, 1-3.

- Waxman, “Military Power and the Posse Comitatus Act,” 302-305.

- Stephen I. Vladeck, “Emergency Power and the Militia Acts,” Yale Law Journal Forum 114 (2004): 152–158.

- United States v. Yunis, 924 F.2d 1086 (D.C. Cir. 1991).

- Doyle, The Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters, 6-9.

- Rachel E. VanLandingham, “Soldiers at the Gates: The Constitutional Dangers of Federalizing the Guard,” University of Illinois Law Review 2021, no. 1 (2021): 105–134.

- Doyle, The Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters, 6-8.

- Waxman, “Military Power and the Posse Comitatus Act,” 302-303.

- Jennifer K. Elsea, The Use of Federal Troops for Disaster Assistance: Legal Issues, Congressional Research Service Report RL33095 (Washington, DC: CRS, 2020), 4–6.

- U.S. Department of Defense, Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA), DoD Directive 3025.18 (Washington, DC: 2018), §§ 3.1–3.3.

- Stephen I. Vladeck, “The National Guard and the Posse Comitatus Act,” Texas National Security Review 3, no. 2 (2020): 89–92.

- VanLandingham, “Soldiers at the Gates,” 112-116.

- Doyle, The Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters, 10-13.

- Jennifer K. Elsea, Homeland Security: The Legal Authority of the Department of Defense to Respond to Domestic Emergencies, Congressional Research Service Report RL33095 (Washington, DC: CRS, 2016), 7–9.

- Matthews, The Posse Comitatus Act and the United States Army, 89-91.

- John R. Brinkerhoff, “The Role of the National Guard in National Defense and Homeland Security,” Journal of Homeland Security, February 2005.

- Stephen I. Vladeck, “Military Forces and the Domestic Enforcement of Law: The Constitutional and Statutory Framework,” Cardozo Law Review 29, no. 3 (2007): 678–684.

- VanLandingham, “Soldiers at the Gates,” 116-120.

- Jeffrey Kaplan, Radical Religion in America: Millenarian Movements from the Far Right to the Children of Noah (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1997), 83–88.

- Michael Barkun, Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 129–131.

- Pete Simi and Steven Windisch, American Militias: State-Level Organization and the Resurgence of Right-Wing Extremism (New York: Routledge, 2020), 44–46.

- Jeffrey Kaplan and Leonard Weinberg, The Emergence of a Euro-American Radical Right (New York: Rutgers University Press, 1998), 123–125.

- David T. Hardy, “The Misuse of Posse Comitatus by the Sovereign Citizen Movement,” Journal of Hate Studies 9, no. 2 (2012): 45–50.

- United States v. Meads, 655 F.3d 1035 (9th Cir. 2011).

- FBI, “Domestic Terrorism: A Chronology of Events and Cases,” FBI.gov, accessed June 14, 2025.

- Ibid.

- Kaplan, Radical Religion in America, 90–92.

- Mark Pitcavage, “The Sovereign Citizen Movement: A Comparative Analysis,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 38, no. 4 (2015): 275–276.

- Barkun, Culture of Conspiracy, 135–137.

- Simi and Windisch, American Militias, 59–61.

- FBI, “Domestic Terrorism: A Chronology.”

- Kaplan, Radical Religion in America, 95–97.

- John R. Schindler, “The Oklahoma City Bombing and the Militia Movement,” Terrorism and Political Violence 13, no. 3 (2001): 22–23.

- Pitcavage, “The Sovereign Citizen Movement,” 278–280.

- Kathleen Belew, Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018), 321–325.

- FBI, “Sovereign Citizens: An Emerging Domestic Threat to Law Enforcement,” FBI.gov, accessed June 14, 2025.

- Belew, Bring the War Home, 329–331.

- FBI, “Domestic Terrorism: A Chronology.”

- Stephen A. Hart and Benjamin P. Thomas, “Far-Right Extremism and the Capitol Attack,” Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 18, no. 2 (2021): 10–12.

- Rachel E. VanLandingham, “Countering Domestic Extremism: Challenges and Strategies,” Harvard Law & Policy Review 15, no. 1 (2021): 140–143.

- FBI, “Domestic Terrorism,” FBI.gov.

- Peter Simi, Steven Windisch, and Steven Chermak, Understanding Extremism: The Role of Identity, Ideology, and Grievance (New York: Routledge, 2017), 210–212.

- American Civil Liberties Union, “Balancing Security and Civil Liberties in Counterterrorism,” ACLU.org, accessed June 14, 2025, https://www.aclu.org/issues/national-security.

- Doyle, The Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters, 1-4.

- Elsea, Homeland Security, 5-7.

- Vladeck, “Military Forces and the Domestic Enforcement of Law,” 675-680.

- VanLandingham, “Soldiers at the Gates,” 110-115.

- Doyle, The Posse Comitatus Act, 10–12.

- Brinkerhoff, “The Role of the National Guard in National Defense and Homeland Security.”

- Elsea, Homeland Security, 12–15.

- Matthews, The Posse Comitatus Act and the United States Army, 95-98.

- VanLandingham, “Countering Domestic Extremism,” 140-142.

- FBI, “Domestic Terrorism: A Chronology of Events and Cases,” FBI.gov, accessed June 14, 2025.

- Vladeck, “Military Forces and the Domestic Enforcement of Law,” 681–683.

- Doyle, The Posse Comitatus Act, 15–17.

- VanLandingham, “Soldiers at the Gates,” 118–120.

- Simi, Windisch, and Chermak, Understanding Extremism, 215-220.

- Elsea, Homeland Security, 18–20.

- Belew, Bring the War Home, 333-335.

- Vladeck, “Military and Law Enforcement Roles in Cybersecurity,” 400-405.

- VanLandingham, “Countering Domestic Extremism,” 143–145.

- Doyle, The Posse Comitatus Act, 22–25.

- Elsea, Homeland Security, 23–25.

- Matthews, The Posse Comitatus Act and the United States Army, 102–104.

- Simi, Windisch, and Chermak, Understanding Extremism, 222-225.

Bibliography

- American Civil Liberties Union. “Balancing Security and Civil Liberties in Counterterrorism.” Accessed June 14, 2025. https://www.aclu.org/issues/national-security.

- Barkun, Michael. Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

- Belew, Kathleen. Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018.

- Bilder, Mary Sarah. The Transatlantic Constitution: Colonial Legal Culture and the Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Bracton, Henry de. On the Laws and Customs of England. Translated by Samuel Thorne. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1968.

- Brinkerhoff, John R. “The Role of the National Guard in National Defense and Homeland Security.” Journal of Homeland Security, February 2005.

- Brown, Richard Maxwell. No Duty to Retreat: Violence and Values in American History and Society. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991.

- Coke, Sir Edward. The Second Part of the Institutes of the Lawes of England. London: 1642.

- Cornell, Saul. The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788–1828. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

- Dobson, R.B. The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. London: Macmillan, 1970.

- Doyle, Charles. The Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters: The Use of the Military to Execute Civilian Law. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2012.

- Elsea, Jennifer K. Homeland Security: The Legal Authority of the Department of Defense to Respond to Domestic Emergencies. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2016.

- —-. The Insurrection Act and Related Authorities: Background and Legislative Issues. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2020.

- —-. The Use of Federal Troops for Disaster Assistance: Legal Issues. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2020.

- FBI. “Domestic Terrorism: A Chronology of Events and Cases.” Accessed June 14, 2025.

- FBI. “Sovereign Citizens: An Emerging Domestic Threat to Law Enforcement.” Accessed June 14, 2025.

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

- Hardy, David T. “The Misuse of Posse Comitatus by the Sovereign Citizen Movement.” Journal of Hate Studies 9, no. 2 (2012): 45–50.

- Hart, Stephen A., and Benjamin P. Thomas. “Far-Right Extremism and the Capitol Attack.” Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 18, no. 2 (2021): 1–20.

- Gillette, William. Retreat from Reconstruction, 1869–1879. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979.

- Hudson, John. The Formation of the English Common Law: Law and Society in England from the Norman Conquest to Magna Carta. London: Routledge, 1996.

- Kaplan, Jeffrey. Radical Religion in America: Millenarian Movements from the Far Right to the Children of Noah. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1997.

- Kaplan, Jeffrey, and Leonard Weinberg. The Emergence of a Euro-American Radical Right. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1998.

- Matthews, Matt. The Posse Comitatus Act and the United States Army: A Historical Perspective. Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2006.

- Morgan, Edmund S. American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia. New York: W.W. Norton, 1975.

- Neely, Mark E. Jr. The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Nelson, William H. The Common Law in Colonial America. Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Pitcavage, Mark. “The Sovereign Citizen Movement: A Comparative Analysis.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 38, no. 4 (2015): 270–285.

- Randall, James G. Constitutional Problems under Lincoln. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1951.

- Richardson, Heather Cox. The Death of Reconstruction: Race, Labor, and Politics in the Post-Civil War North, 1865–1901. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Schindler, John R. “The Oklahoma City Bombing and the Militia Movement.” Terrorism and Political Violence 13, no. 3 (2001): 18–27.

- Simi, Pete, and Steven Windisch. American Militias: State-Level Organization and the Resurgence of Right-Wing Extremism. New York: Routledge, 2020.

- Simi, Pete, Steven Windisch, and Steven Chermak. Understanding Extremism: The Role of Identity, Ideology, and Grievance. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Stubbs, William. Select Charters and Other Illustrations of English Constitutional History. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1900.

- Summerson, Henry. “Law and Order in the Medieval English Town: The Use of the ‘Hue and Cry’.” The English Historical Review 103, no. 407 (1988): 583–605.

- Tomlins, Christopher. Law, Labor, and Ideology in the Early American Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- United States v. Meads, 655 F.3d 1035 (9th Cir. 2011).

- United States v. Red Feather, 392 F. Supp. 916 (D.S.D. 1975).

- United States v. Yunis, 924 F.2d 1086 (D.C. Cir. 1991).

- U.S. Department of Defense. Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA). DoD Directive 3025.18. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Defense, 2018.

- VanLandingham, Rachel E. “Countering Domestic Extremism: Challenges and Strategies.” Harvard Law & Policy Review 15, no. 1 (2021): 135–150.

- —-. “Soldiers at the Gates: The Constitutional Dangers of Federalizing the Guard.” University of Illinois Law Review 2021, no. 1 (2021): 105–134.

- —-. “Emergency Power and the Militia Acts.” Yale Law Journal Forum 114 (2004): 149–158.

- —-. “Military Forces and the Domestic Enforcement of Law: The Constitutional and Statutory Framework.” Cardozo Law Review 29, no. 3 (2007): 675–694.

- —-. “The National Guard and the Posse Comitatus Act.” Texas National Security Review 3, no. 2 (2020): 88–94.

- —-. “The Posse Comitatus Act Explained.” Texas Law Review 93, no. 5 (2015): 1171–1202.

- Waxman, Matthew C. “Military Power and the Posse Comitatus Act.” Journal of National Security Law & Policy 2, no. 2 (2008): 295–310.

- —-. “The Use of Military Force in Homeland Defense: Law and Policy.” Columbia Journal of Transnational Law 43, no. 2 (2005): 437–472.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.16.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.