One legacy of perseverance and productivity, and another of profound injustice.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Shirley Plantation stands not only as a relic of early American history but also as a complex symbol of continuity, privilege, and moral contradiction. Located on the banks of the James River in Charles City County, Virginia, it is the oldest active plantation in the United States and the oldest family-owned business, having operated continuously since its establishment in 1613. Owned and managed by eleven successive generations of the Hill-Carter family, the plantation represents one of the earliest examples of Anglo-American agribusiness, surviving revolutions, civil war, and modern economic upheaval.

But beneath the graceful Georgian architecture and manicured grounds lies a legacy inextricably bound to the institution of slavery. Shirley Plantation was not merely a home and business—it was a site of forced labor, racial exploitation, and human suffering. Any honest appraisal of its history must fully engage with this dual legacy: one of perseverance and productivity, and another of profound injustice.

Founding and Early Colonial Years

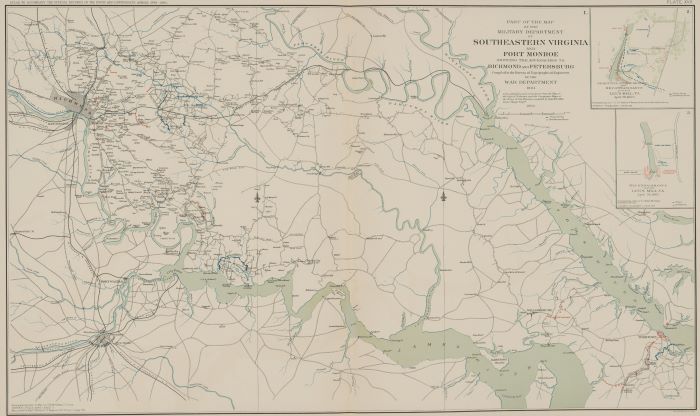

Shirley Plantation’s history begins in the earliest decades of English colonization in North America. Situated along the James River in what became Charles City County, Virginia, the plantation was established in 1613, just six years after the founding of Jamestown. It emerged out of the Virginia Company of London’s efforts to encourage settlement and economic exploitation of the Chesapeake region through land grants and corporate models of governance. These incentives were designed not only to populate the struggling colony but to ensure returns for investors in England. One such grant was issued to Captain Edward Hill I, who received a patent for land that would become the foundation of Shirley Plantation. The choice of location—on fertile lowland near a navigable river—was strategic, enabling access to transatlantic trade routes and productive agricultural soil ideal for tobacco cultivation.1

The early decades of Shirley Plantation coincided with the volatile and often violent process of English colonial expansion, including tense and frequently hostile relations with the Powhatan Confederacy. The surrounding area saw repeated cycles of conflict, especially during the Anglo-Powhatan Wars (1610–1646), which significantly shaped settlement patterns and colonial survival strategies. Like other plantations in the Tidewater region, Shirley was fortified and developed as both a residence and a production center. Edward Hill I’s leadership within the colonial political and military hierarchy—serving as Speaker of the House of Burgesses and briefly as acting governor—secured the Hill family’s status as part of Virginia’s emerging elite.2 In this role, Hill helped shape the colonial political economy, reinforcing a system that tied land ownership, agriculture, and political power together in a mutually reinforcing loop.

Labor on Shirley Plantation in its formative years was drawn primarily from indentured servants, a system common throughout the English Atlantic world during the 17th century. These servants, often poor and landless men from England and Ireland, agreed to years of service in exchange for passage to the colonies. This system, however, proved insufficient for the plantation’s long-term labor demands, especially as the profitability of tobacco increased and the mortality rate among indentured servants remained high. By the late 1600s, African laborers were increasingly imported, initially under ambiguous legal status but gradually transformed into chattel slaves through evolving colonial legislation. This shift was part of a broader trend throughout the Chesapeake, where the racialization of labor became a cornerstone of plantation economics.3 Shirley thus transitioned from a mixed labor system to one increasingly defined by permanent racial slavery by the early 18th century.

As Shirley grew in prosperity, so did its integration into the Atlantic economy. Tobacco, the colony’s primary export, was shipped directly to England, often in exchange for finished goods, textiles, and other commodities unavailable in the colonies. The plantation’s riverfront location was essential to this economy, as it allowed direct loading of hogsheads of tobacco onto ships bound for London and other ports. Records from the period show that Shirley participated in both legal and gray-market trading networks, a common practice among elite planters who exploited gaps in imperial oversight.4 This economic success, however, was precarious and vulnerable to fluctuations in market demand, weather, and war. Nonetheless, by the end of the 17th century, the Hill family had firmly entrenched itself as one of the First Families of Virginia, a social designation that reinforced both inherited wealth and political influence.

By the early 18th century, Shirley Plantation’s transformation from a frontier outpost to a dynastic estate was well underway. The initial wooden structures were replaced with more permanent buildings, culminating in the construction of the current Georgian mansion in the 1720s under Edward Hill III and his daughter Anne Hill, who married Charles Carter of the powerful Carter family.5 This union symbolized the fusion of two prominent dynasties and ensured the continuation of the estate under a consolidated lineage. The plantation had by then become a microcosm of Virginia’s colonial society—stratified, agrarian, and racially divided. Though the Hill-Carter family would later play prominent roles in the American Revolution and beyond, their ascent was rooted in the colonial era’s violent dispossession of Native lands and the commodification of human beings. The early colonial years of Shirley Plantation thus encapsulate the broader patterns of settler colonialism, economic ambition, and racialized labor that defined early Virginia.

The Hill-Carter Dynasty and Architectural Development

Shirley Plantation had become not only a profitable agricultural enterprise in the early 18th century but also the seat of an emerging dynastic power. The union of Anne Hill, daughter of Edward Hill III, with Charles Carter of Corotoman, one of the wealthiest and most politically connected planters in colonial Virginia, fused two of the colony’s most prominent families. The Carters descended from Robert “King” Carter, a former acting governor and land magnate whose descendants intermarried extensively with other First Families of Virginia. This strategic marriage ensured Shirley’s continued prominence, transferring both material assets and political capital into the Hill-Carter line.6 Charles and Anne’s son, Charles Carter of Shirley (1732–1806), inherited the estate and began to transform it into a lasting symbol of gentry power and architectural refinement. As much as Shirley was a working plantation, it also became a performative space of authority, legitimacy, and inherited status in colonial society.7

The most enduring symbol of the dynasty’s legacy is the Georgian-style Great House at Shirley, constructed between 1723 and 1738. The house remains one of the finest surviving examples of 18th-century plantation architecture in North America. Its proportions, symmetry, and brick construction reflect the aesthetic principles of Palladian classicism, which had been disseminated among the Virginia gentry through English architectural pattern books such as those by James Gibbs and Colen Campbell.8 The house’s hipped roof, large chimneys, and balanced façade reflected not only a growing colonial sophistication but also aspirations toward an English aristocratic ideal. Unlike many plantation homes that were constructed in piecemeal fashion, Shirley’s mansion was clearly conceived as a unified design, incorporating a formal entrance court and carefully aligned outbuildings, including kitchens, smokehouses, and stables. These features were intended to broadcast order, control, and permanence.

A particularly notable feature of the mansion is its so-called “flying staircase”—a double-helix, open-riser stairwell that appears to float upward without visible support. This architectural marvel, constructed without nails, relied on precisely fitted wooden joints and was likely inspired by contemporary British designs, though few examples survive in colonial America.9 The staircase served a symbolic function as much as a practical one: it was a physical demonstration of engineering mastery and elite taste, reinforcing the Carters’ cultural fluency and wealth. Inside the house, the layout followed the typical Georgian plan with a central passage flanked by rooms of equal size, further embodying Enlightenment ideals of balance and rational design. The ornamentation, from paneling to fireplaces, suggests that Shirley was a domestic theater of elite identity as much as a family residence.10

The plantation itself was organized around this architectural nucleus, reinforcing the hierarchical logic of Virginia’s slaveholding society. While the main house stood at the apex of the landscape—both physically and socially—the enslaved population who built, maintained, and labored on the estate remained relegated to peripheral quarters and fields. The Carters owned dozens of enslaved people throughout the 18th century, many of whom were skilled artisans—blacksmiths, carpenters, coopers—whose labor enabled the construction and operation of Shirley’s buildings and agricultural infrastructure.11 The house’s grandeur, then, cannot be disentangled from the coerced labor and racial violence that underwrote its creation. As with other Tidewater plantations, Shirley’s architectural elegance masked the brutal realities of slavery that sustained its opulence and dynastic ambitions.

By the end of the 18th century, Shirley Plantation had become not just a familial estate but a symbol of the enduring power of Virginia’s planter aristocracy. During the American Revolution, members of the Carter family supported independence, but the plantation economy they defended remained rooted in unfree labor and social stratification.12 The continuity of the Hill-Carter dynasty across centuries—and through wars, economic shifts, and political upheavals—was materially embodied in the mansion they constructed. Remarkably, the estate has remained in the hands of Hill-Carter descendants to this day, making it not only the oldest family-owned business in the United States but also a case study in the durability of elite continuity. In this way, Shirley Plantation stands as both architectural achievement and historical artifact, revealing the intertwined legacies of family, power, and exploitation at the heart of the American colonial experience.

Slavery at Shirley Plantation

From the late 17th century onward, Shirley Plantation developed into a thriving agricultural estate whose profitability was increasingly tied to the institution of slavery. Like most Tidewater plantations, Shirley relied on enslaved African labor to produce its primary cash crop—tobacco—and to manage every aspect of its domestic and agricultural operations. As the plantation economy matured, the racialization of labor became entrenched, and Shirley, like other Virginia estates, shifted from a mixed labor system to one that relied almost exclusively on chattel slavery. Enslaved people were not only the backbone of the plantation’s labor force but also integral to the growth of the Hill-Carter dynasty’s wealth, influence, and cultural standing. Inventories and tax records from the 18th and early 19th centuries reveal that Shirley’s owners regularly held between 40 and 90 enslaved people at any given time.13 These individuals were treated as both property and capital—assets to be bought, sold, mortgaged, and inherited.

The enslaved community at Shirley Plantation performed a wide array of tasks that extended beyond field labor. While many were tasked with cultivating, harvesting, and processing tobacco, others were artisans, blacksmiths, coopers, and carpenters, providing essential skills that maintained the plantation’s self-sufficiency. Domestic slaves worked within the main house, cooking meals, cleaning rooms, laundering linens, and caring for the children of the Carter family.14 Enslaved individuals were also responsible for operating ferries, maintaining livestock, repairing buildings, and crafting barrels used in tobacco storage. These laborers often possessed technical proficiency and expertise, yet they lived under the constant threat of violence, separation from family, and complete lack of autonomy. Their skills, while crucial to the plantation’s function, were not rewarded with freedom or recognition, only deeper entrenchment in a system that commodified their very existence.

The living conditions for enslaved individuals at Shirley were harsh and dehumanizing. Housing consisted of small, one-room cabins, often located in peripheral areas of the estate, hidden from the aesthetic center represented by the mansion and its gardens. These dwellings, made from logs or brick with dirt floors and minimal furnishings, offered scant protection from the elements.15 Enslaved families frequently lived in overcrowded conditions, and their diets were poor—typically consisting of cornmeal, salt pork, and seasonal vegetables, supplemented by foraged foods or what they could grow in small personal plots. Despite these challenges, the enslaved population at Shirley, like those elsewhere, built complex social and cultural lives. They formed kinship networks, practiced religious rituals—both African-derived and Christianized—and found ways to resist the psychological and physical constraints of bondage, even if only in subtle acts of defiance or self-preservation.

The Carter family, like many Virginia planters, rationalized their ownership of enslaved people through a blend of economic self-interest, paternalistic ideology, and racial prejudice. Family letters and plantation records reflect a worldview in which enslaved labor was seen as both a birthright and a necessity. Some Carters viewed themselves as benevolent masters, believing that their treatment of slaves was “kind” or “Christian,” even while they participated in practices such as the breakup of families through sale or the violent punishment of runaways.16 Instances of resistance—such as work slowdowns, tool-breaking, escape attempts, and the establishment of clandestine religious gatherings—challenged the planter class’s illusion of control and exposed the constant tensions underlying the plantation order. Enslaved people were not passive victims but active agents who navigated a world of oppression with resilience and ingenuity.

By the time of the Civil War, slavery had become not only central to Shirley’s economy but deeply interwoven with its social identity. The Hill-Carter family, like many of their peers, supported the Confederacy, seeing the war as a defense of their way of life, which included the right to own human beings. Shirley, however, was spared physical destruction during the war, in part due to the Union Army’s recognition of its historical significance and its strategic location along the James River.17 After emancipation, many formerly enslaved individuals remained on or near the estate, continuing to work the land under new exploitative systems such as sharecropping or tenant farming. Yet the trauma of slavery at Shirley left a deep and lasting imprint, one that has only recently begun to be publicly acknowledged through historical interpretation and preservation efforts. The elegant façade of Shirley’s architecture cannot obscure the brutal reality that it was built, sustained, and enriched by the labor of enslaved people whose voices are only now being more fully recovered.

The Revolutionary and Antebellum Periods

During the Revolutionary War, Shirley Plantation, like many elite estates in Virginia, found itself caught between economic instability and shifting political loyalties. Although the Carters had long benefited from the British mercantile system and aristocratic privileges, members of the family, including Charles Carter of Shirley, supported the cause of American independence.18 This allegiance, however, was pragmatic as much as ideological. The Revolution threatened the financial basis of the plantation economy by disrupting transatlantic trade and depreciating currency. Moreover, enslaved people at Shirley, as elsewhere, interpreted the revolutionary rhetoric of liberty and natural rights in their own terms. British military proclamations, such as Lord Dunmore’s 1775 offer of freedom to slaves who joined royal forces, incited unrest and posed both moral and material threats to Virginia planters.19 There is no direct documentation of mass flight from Shirley during the war, but its proximity to the James River made it particularly vulnerable to raids and evacuations.

Following the Revolution, Shirley Plantation entered the antebellum period marked by a dual effort to restore economic prosperity and reassert social dominance. The new American republic did not fundamentally alter the planter aristocracy’s grip on political power or their reliance on enslaved labor. The Carters, through shrewd land management and social alliances, remained one of the region’s most influential families.20 Agricultural production gradually diversified beyond tobacco into wheat and corn, a shift driven by soil exhaustion, market conditions, and transportation innovations. The James River and Kanawha Canal system expanded economic access and integrated Shirley into broader national markets. But despite these adaptations, the plantation retained its feudal-like structure: a core of elite white landowners, supported by a deeply entrenched and racially stratified labor system.

The antebellum period was also a time of reinvention and historical curation at Shirley. As romanticized notions of the “Old South” began to circulate in literature and public discourse, the Hill-Carter family began consciously preserving the estate’s colonial-era appearance.21 This act of architectural and landscape conservation served to root the family’s authority in a tangible and idealized past, emphasizing continuity and legitimacy. Even as other planters modernized or demolished their homes to reflect newer styles, Shirley retained its Georgian character, projecting a kind of timeless authority. Visitors to the plantation were often impressed by its stately proportions and aura of tradition. These aesthetics, however, were carefully maintained through the constant labor of enslaved people, who repaired buildings, tended gardens, and ensured that the estate’s presentation aligned with its master’s social image.

At the same time, tensions simmered beneath this patina of antebellum grandeur. Enslaved people at Shirley endured the contradictions of a society proclaiming liberty while denying them basic humanity. The growing abolitionist movement in the North and rising sectional tensions nationally brought renewed scrutiny to the slaveholding class.22 Though the Carters were not politically radical, they were aware of the rising threat to their way of life. Like other Virginia planters, they supported efforts to defend slavery through legislation and moral argument, framing themselves as paternalistic guardians rather than exploiters. Yet internal plantation records—such as overseer reports and family letters—betray the fragility of this self-conception. Resistance among enslaved people, declining soil fertility, and increasing debt were symptoms of a system that was morally and economically untenable, even if it persisted.

By the 1850s, Shirley Plantation stood as a symbol of both endurance and impending crisis. The estate was still inhabited by multiple generations of the Hill-Carter family, who continued to host political and social gatherings, reinforcing their elite status.23 Yet even as they clung to a nostalgic vision of aristocratic Virginia, the nation was barreling toward civil war. Shirley, like many Tidewater plantations, was deeply embedded in the Confederate vision of a rural, slaveholding republic. The antebellum decades thus represent a paradoxical chapter in the plantation’s history: a period of cultural consolidation and imagined permanence shadowed by the deepening moral contradictions and unsustainable economics of slavery. As the 1860s approached, Shirley remained beautiful, dignified—and increasingly out of time.

Civil War and Emancipation

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Shirley Plantation stood as a symbol of the entrenched Southern aristocracy and the contradictions that would soon engulf the nation in bloodshed. The Hill-Carter family, like many elite Virginian dynasties, supported the Confederacy both ideologically and materially. Shirley’s geographic location on the James River placed it near key theaters of war, and although it was never burned or ransacked, the war deeply disrupted its economy, labor system, and social order.24 Union troops, recognizing the historical significance of the estate and possibly swayed by the Carters’ dignified appeals for its protection, spared the house from destruction. Nevertheless, its fields lay fallow for seasons, river trade was choked off, and many of the enslaved laborers who once sustained the estate took the opportunity to flee toward Union lines as emancipation drew closer.25

Despite Confederate sympathies, Shirley found itself within Union-controlled territory after the Peninsula Campaign of 1862. The Union Army, having captured strategic points along the James River, used nearby Berkeley Plantation as General McClellan’s headquarters, and Shirley became a zone of relative calm amid broader turmoil. This ironic preservation—Confederate planter homes protected under Union occupation—was not uncommon, especially in areas considered tactically neutral or historically significant.26 Even as Union forces patrolled the area, however, the plantation’s economic model had been fundamentally broken. With enslaved people fleeing or being conscripted for labor by Union soldiers, the Carters struggled to maintain agricultural productivity. Letters from family members reflect a mixture of bewilderment and fear, as they watched their old world disintegrate and faced the impending loss of their enslaved workforce, long the foundation of their prosperity.

The legal abolition of slavery through the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 transformed Shirley and other plantations from centers of forced labor into battlegrounds of labor renegotiation. Like many planters, the Hill-Carters attempted to secure labor through sharecropping arrangements and wage labor contracts with formerly enslaved individuals, some of whom remained on the land due to lack of alternatives.27 These agreements were often exploitative, favoring landowners in disputes over wages, debts, and housing. While some freedpeople tried to claim greater autonomy by working independently or moving to nearby towns like Hopewell or Petersburg, others stayed on plantations like Shirley, either out of familial connection to the land or lack of viable economic alternatives. The transition was not smooth; it involved constant negotiation over freedom’s meaning, rights, and the structure of rural Southern labor.

In the immediate postwar years, Shirley faced steep economic decline, a common fate for once-prosperous estates across the defeated South. The loss of enslaved labor, Confederate currency, and access to national markets devastated planter incomes. The Hill-Carter family, like many others, resorted to selling land, leasing properties, and forming new economic strategies simply to remain solvent.28 For a time, Shirley functioned more as a struggling farm than a thriving plantation. The post-emancipation transformation of Shirley was less about ideological reformation than about survival. The Carters sought to preserve their legacy and land even as they adjusted—often reluctantly—to a new world in which they no longer held complete power over the labor force. This was a time of profound disorientation, particularly for white elites who had long conflated land ownership with authority over human lives.

Despite economic hardship, the Hill-Carter family remained on the property, and Shirley’s preservation into the 20th century owes much to their continuity of residence. The plantation house stood as a relic of the antebellum world even as its foundation had irrevocably shifted.29 The legacy of slavery lingered in the structures and social dynamics of the region; while slavery had formally ended, the racial hierarchies it established were deeply embedded in Virginia’s political and cultural systems. For those formerly enslaved at Shirley, emancipation did not bring instant equality or opportunity, but it marked the beginning of a long and unfinished struggle toward self-determination. The Civil War and emancipation had reshaped Shirley Plantation profoundly—destroying its old economic model, altering its labor structure, and transforming it from a bastion of aristocracy into a symbol of survival and transition in the New South.

Postbellum Continuity and Historical Memory

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Shirley Plantation confronted the same economic and social upheaval that plagued the wider South, but the Hill-Carter family maintained a rare continuity of ownership that would help shape both the property’s preservation and its evolving historical narrative. Stripped of enslaved labor and weakened by agricultural decline, the family adapted to the realities of the post-emancipation era by leasing portions of their land, experimenting with new crop models, and eventually capitalizing on the plantation’s historical value.30 While many neighboring estates fell into disrepair or changed hands, Shirley survived due to the family’s willingness to remain on the land and adjust their expectations. This endurance, however, came with a selective memory. The romanticized image of the antebellum South, sanitized of its dependence on slavery, became an increasingly dominant feature in how Shirley was presented to visitors and remembered by its stewards.31

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the plantation house and grounds had become symbolic of a “lost cause” mythology that celebrated Southern gentility while minimizing or erasing the brutality of slavery. Shirley was featured in regional travel guides, romantic literature, and eventually in national preservation circles as a pristine example of colonial architecture and continuity.32 The Hill-Carter family’s aristocratic lineage and support for the Confederacy were emphasized as marks of noble heritage, while the lives and labor of the hundreds of enslaved individuals who built and sustained the plantation remained largely absent from public-facing narratives. This selective storytelling mirrored broader patterns in the South, where memory became a battleground. Through reunions, local histories, and historical societies, elite white families constructed and reinforced a legacy of honor, rooted in architecture and bloodlines but divorced from the violence and inequality that underpinned that legacy.33

The rise of historical preservation in the 20th century offered the Hill-Carters an opportunity to reposition Shirley Plantation not just as a home, but as a cultural artifact. In 1960, it was designated a National Historic Landmark, a status that provided recognition and some federal protections but also reinforced prevailing narratives of elite continuity.34 The preservation movement often privileged architectural and genealogical elements over the complex realities of labor, race, and class. Tours emphasized Shirley’s Georgian brickwork, the hand-carved pine staircases, and the plantation’s role in the American Revolution, while omitting or downplaying its significance as a site of enslavement. The plantation became a site where public memory was curated, often to comfort and educate without discomforting the visitor. This approach, while financially beneficial in drawing tourists, delayed a more honest reckoning with the site’s full historical implications.

Recent decades have witnessed a gradual shift in how Shirley Plantation presents its history. Inspired by broader trends in public history and the influence of African American scholars and activists, some attempts have been made to include the stories of enslaved people in the plantation’s interpretation.35 These efforts remain incomplete and sometimes tentative, constrained by the family’s continued ownership and the challenges of disrupting long-held narratives. However, the inclusion of archaeological studies, reinterpretive signage, and oral history projects suggests a growing awareness of the plantation’s dual legacy—as both a monument of architectural beauty and a site of human suffering. While Shirley is still owned and operated by Hill-Carter descendants, the very fact of its continued existence now demands a deeper engagement with what that continuity represents, and how it has shaped historical memory.

In this sense, Shirley Plantation stands as a microcosm of the American South’s struggle with its past. Its endurance is remarkable—one of the few plantations in America to remain under the same family’s stewardship since the 17th century. Yet that endurance also embodies the unresolved tensions of Southern memory: the conflict between pride in heritage and the necessity of confronting injustice.36 As the nation continues to wrestle with issues of race, history, and identity, places like Shirley serve both as mirrors and as teachers. They reflect the stories we have long told ourselves and offer the possibility of telling new, fuller truths. Whether the plantation will fully embrace this role remains to be seen, but the conversation it provokes—about continuity, ownership, and remembrance—is essential to understanding America’s evolving relationship with its past.

Conclusion

Shirley Plantation stands today as a living monument to the complicated legacy of American history. It is a symbol of family endurance, architectural brilliance, and economic resilience. But it is equally, if not more importantly, a reminder of the brutal institution of slavery and the lives consumed by a system designed for profit and control.

To truly appreciate Shirley Plantation’s place in American history, one must grapple with both its grandeur and its grim underpinnings. The site offers an opportunity not only to explore the past but to ask urgent questions about historical memory, racial justice, and the moral costs of economic success.

Only through such full engagement can we honor the whole truth—one that includes the triumphs of endurance and the tragedies of exploitation alike.

Appendix

Endnotes

- T. H. Breen, Tobacco Culture: The Mentality of the Great Tidewater Planters on the Eve of Revolution (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985).

- Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (New York: W. W. Norton, 1975).

- Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998).

- Allan Kulikoff, Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680–1800 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986).

- Martha W. McCartney, Virginia Immigrants and Adventurers, 1607–1635: A Biographical Dictionary (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2007).

- Emory G. Evans, A “Topping People”: The Rise and Decline of Virginia’s Old Political Elite, 1680–1790 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2009), 96–99.

- Rhys Isaac, The Transformation of Virginia, 1740–1790 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982), 44–47.

- Dell Upton, Holy Things and Profane: Anglican Parish Churches in Colonial Virginia (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), 168.

- William B. O’Neal, Architecture in Virginia: An Official Guide to the Old Dominion (New York: Walker and Company, 1968), 128.

- Cary Carson, Norman F. Barka, William M. Kelso, Garry Wheeler Stone, and Dell Upton, “Impermanent Architecture in the Southern American Colonies,” Winterthur Portfolio 16, no. 2/3 (Summer–Autumn 1981): 135–95.

- Lorena S. Walsh, Motives of Honor, Pleasure, and Profit: Plantation Management in the Colonial Chesapeake, 1607–1763 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 252–55.

- Drew Gilpin Faust, A Sacred Circle: The Dilemma of the Intellectual in the Old South, 1840–1860 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977), 9–11.

- Walsh, Motives of Honor, Pleasure, and Profit, 395-400.

- Jennifer L. Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 104–109.

- John Michael Vlach, Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 33–36.

- Charles B. Dew, Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001), 50–52.

- David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 78–82.

- Evans, A “Topping People”, 189-192.

- Sylvia R. Frey, Water from the Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), 81–86.

- Thad W. Tate, The Negro in Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1965), 67–70.

- Catherine Clinton, The Plantation Mistress: Woman’s World in the Old South (New York: Pantheon, 1982), 146–149.

- Eugene D. Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (New York: Vintage, 1976), 610–617.

- William W. Freehling, The Road to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 440–445.

- Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 144–147.

- Ira Berlin, Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 196–199.

- John Michael Priest, Antietam: The Soldiers’ Battle (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 322–325.

- Leon F. Litwack, Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (New York: Vintage Books, 1980), 248–254.

- Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 111–114.

- Blight, Race and Reunion, 117-122.

- Vlach, Back of the Big House, 198-201.

- Blight, Race and Reunion, 254-259.

- Clinton, The Plantation Mistress, 231.

- Gaines M. Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 132–136.

- Upton, Holy Things and Profane, 266.

- Toni Morrison, “The Site of Memory,” in Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, ed. William Zinsser (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1995), 83–102.

- Edward T. Linenthal, Sacred Ground: Americans and Their Battlefields (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 174–178.

- T. H. Breen, Tobacco Culture: The Mentality of the Great Tidewater Planters on the Eve of Revolution (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985).

- Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (New York: W. W. Norton, 1975).

- Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998).

- Allan Kulikoff, Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680–1800 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986).

- Martha W. McCartney, Virginia Immigrants and Adventurers, 1607–1635: A Biographical Dictionary (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2007).

- Emory G. Evans, A “Topping People”: The Rise and Decline of Virginia’s Old Political Elite, 1680–1790 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2009), 96–99.

- Rhys Isaac, The Transformation of Virginia, 1740–1790 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982), 44–47.

- Dell Upton, Holy Things and Profane: Anglican Parish Churches in Colonial Virginia (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), 168.

- William B. O’Neal, Architecture in Virginia: An Official Guide to the Old Dominion (New York: Walker and Company, 1968), 128.

- Cary Carson, Norman F. Barka, William M. Kelso, Garry Wheeler Stone, and Dell Upton, “Impermanent Architecture in the Southern American Colonies,” Winterthur Portfolio 16, no. 2/3 (Summer–Autumn 1981): 135–95.

- Lorena S. Walsh, Motives of Honor, Pleasure, and Profit: Plantation Management in the Colonial Chesapeake, 1607–1763 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 252–55.

- Drew Gilpin Faust, A Sacred Circle: The Dilemma of the Intellectual in the Old South, 1840–1860 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977), 9–11.

- Walsh, Motives of Honor, Pleasure, and Profit, 395-400.

- Jennifer L. Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 104–109.

- John Michael Vlach, Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 33–36.

- Charles B. Dew, Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001), 50–52.

- David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 78–82.

- Evans, A “Topping People”, 189-192.

- Sylvia R. Frey, Water from the Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), 81–86.

- Thad W. Tate, The Negro in Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1965), 67–70.

- Catherine Clinton, The Plantation Mistress: Woman’s World in the Old South (New York: Pantheon, 1982), 146–149.

- Eugene D. Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (New York: Vintage, 1976), 610–617.

- William W. Freehling, The Road to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 440–445.

- Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 144–147.

- Ira Berlin, Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 196–199.

- John Michael Priest, Antietam: The Soldiers’ Battle (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 322–325.

- Leon F. Litwack, Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (New York: Vintage Books, 1980), 248–254.

- Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 111–114.

- Blight, Race and Reunion, 117-122.

- Vlach, Back of the Big House, 198-201.

- Blight, Race and Reunion, 254-259.

- Clinton, The Plantation Mistress, 231.

- Gaines M. Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 132–136.

- Upton, Holy Things and Profane, 266.

- Toni Morrison, “The Site of Memory,” in Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, ed. William Zinsser (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1995), 83–102.

- Edward T. Linenthal, Sacred Ground: Americans and Their Battlefields (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 174–178.

Bibliography

- Berlin, Ira. Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003.

- ———. Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Blight, David W. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Breen, T. H. Tobacco Culture: The Mentality of the Great Tidewater Planters on the Eve of Revolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985.

- Carson, Cary, et al. “Impermanent Architecture in the Southern American Colonies.” Winterthur Portfolio 16, no. 2/3 (Summer–Autumn 1981): 135–95.

- Clinton, Catherine. The Plantation Mistress: Woman’s World in the Old South. New York: Pantheon, 1982.

- Dew, Charles B. Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001.

- Evans, Emory G. A “Topping People”: The Rise and Decline of Virginia’s Old Political Elite, 1680–1790. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2009.

- Faust, Drew Gilpin. A Sacred Circle: The Dilemma of the Intellectual in the Old South, 1840–1860. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977.

- ———. This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008.

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

- Foster, Gaines M. Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Freehling, William W. The Road to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Frey, Sylvia R. Water from the Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

- Genovese, Eugene D. Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. New York: Vintage, 1976.

- Isaac, Rhys. The Transformation of Virginia, 1740–1790. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982.

- Kulikoff, Allan. Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680–1800. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986.

- Linenthal, Edward T. Sacred Ground: Americans and Their Battlefields. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991.

- Litwack, Leon F. Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery. New York: Vintage Books, 1980.

- McCartney, Martha W. Virginia Immigrants and Adventurers, 1607–1635: A Biographical Dictionary. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2007.

- Morgan, Edmund S. American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia. New York: W. W. Norton, 1975.

- Morgan, Jennifer L. Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

- Morrison, Toni. “The Site of Memory.” In Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, edited by William Zinsser, 83–102. Link. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1995.

- O’Neal, William B. Architecture in Virginia: An Official Guide to the Old Dominion. New York: Walker and Company, 1968.

- Priest, John Michael. Antietam: The Soldiers’ Battle. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Tate, Thad W. The Negro in Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg. Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1965.

- Upton, Dell. Holy Things and Profane: Anglican Parish Churches in Colonial Virginia. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

- Vlach, John Michael. Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

- Walsh, Lorena S. Motives of Honor, Pleasure, and Profit: Plantation Management in the Colonial Chesapeake, 1607–1763. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.17.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.