By the 19th century, American historiography began to professionalize and diversify.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The development of American historiography in the 18th and 19th centuries mirrors the evolution of the United States itself—from a collection of disparate colonies to an expansive, ideologically driven republic. In the early stages of the 18th century, American historical writing was largely derivative, shaped by colonial chroniclers and clerical figures who framed the American past in providential terms, seeing the New World as a divine extension of European destiny. As the Revolution approached and the nation emerged, however, historians increasingly turned to narratives that emphasized liberty, republican virtue, and the unique character of the American experiment. Figures such as David Ramsay and Mercy Otis Warren used history to solidify national identity, framing the struggle for independence as part of a broader Enlightenment vision of human progress.

By the 19th century, American historiography began to professionalize and diversify. The rise of Romantic nationalism infused historical writing with mythic qualities, most famously in the work of George Bancroft, who cast the nation’s expansion as both inevitable and divinely sanctioned. Simultaneously, historians such as William H. Prescott, John Lothrop Motley, and Francis Parkman applied literary flair and archival research to international subjects, helping establish American history writing as both erudite and imaginative. Yet this period also saw the exclusion of many voices—particularly those of women, Indigenous peoples, African Americans, and working-class individuals—from mainstream historical narratives. As sectional tensions mounted in the antebellum period and culminated in the Civil War, historiography itself became a battleground over memory and meaning, with competing visions of the American story emerging along regional, ideological, and racial lines. Together, the historians of the 18th and 19th centuries laid both the intellectual foundation and the contested terrain upon which modern American historical scholarship would continue to build.

Chronicling a Nation Born

David Ramsay (1749–1815)

David Ramsay stands as one of the earliest and most influential American historians, whose work helped shape the emerging national identity in the aftermath of the Revolutionary War. A physician by training and a statesman by experience, Ramsay brought both analytical rigor and patriotic fervor to his historical writings. His most notable work, The History of the American Revolution (1789), was among the first attempts by an American-born writer to produce a comprehensive, two-volume account of the Revolution.1 Rather than merely recounting events, Ramsay aimed to provide a philosophical and political interpretation of the conflict, aligning the American cause with Enlightenment ideals of liberty, self-governance, and human progress. Influenced by the Scottish Enlightenment, Ramsay framed the Revolution not as a rebellion but as a rational and moral struggle against tyranny—a necessary step in the advancement of civil society.2 In doing so, he sought to cultivate civic virtue and national unity, offering Americans a usable past rooted in reason, sacrifice, and collective destiny. His writing eschewed the florid embellishments of earlier colonial chroniclers in favor of a more structured, analytical approach, helping to establish history as a tool for moral instruction and political cohesion in the nascent republic.

Yet Ramsay’s historiographical legacy is also shaped by the limitations and complexities of his time. While his work was groundbreaking in its ambition and scope, it reflected the prevailing assumptions of elite white male thinkers in the post-revolutionary era. His histories largely ignored or marginalized the experiences and perspectives of Native Americans, enslaved Africans, and women, reinforcing a narrative of republican virtue that centered on Anglo-American political actors.3 Ramsay’s portrayal of African Americans, particularly in his History of South Carolina (1809), was paternalistic at best, and he often justified slavery as a pragmatic necessity for Southern stability.4 Moreover, his writing was deeply tied to the project of national mythmaking, privileging consensus over conflict and continuity over disruption. Nevertheless, Ramsay’s emphasis on rational analysis, empirical evidence, and narrative clarity laid the groundwork for future historians. His efforts marked a pivotal shift from providential interpretations to Enlightenment-inflected narratives, and his work serves as a vital link between the political culture of the Founding generation and the professionalization of American historiography in the nineteenth century.

Jeremy Belknap (1744–1798)

Jeremy Belknap was a pioneering figure in early American historiography whose work blended clerical discipline with Enlightenment rigor, marking a transition toward a more methodical and source-driven practice of historical writing. A Congregational minister in New Hampshire, Belknap is best known for his History of New Hampshire (1784–1792), a three-volume work that exemplified his commitment to factual accuracy, comprehensive documentation, and critical inquiry.5 Unlike many of his contemporaries who relied heavily on rhetorical flourish or providential interpretation, Belknap grounded his narrative in primary sources, correspondence, and public records, signaling a deliberate move toward historical professionalism. He meticulously gathered data from town records, letters, and oral accounts, often appending notes and citations—an uncommon practice at the time, but one that foreshadowed modern academic standards.6 His work not only chronicled political developments but also included economic, religious, and cultural observations, illustrating a holistic vision of regional history that sought to integrate the complexity of lived experience into the broader national narrative.

Belknap’s historical philosophy was deeply influenced by Enlightenment ideals of rationality and empirical inquiry, but it was also shaped by his theological convictions and civic engagement. As the founder of the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1791—the first such institution in the United States—Belknap institutionalized the collection and preservation of historical documents, reflecting his belief that history was essential to the moral and political health of the republic.7 His approach to history was neither purely antiquarian nor narrowly celebratory; instead, he saw it as a means of moral instruction and civic education, capable of guiding future generations through the lessons of the past. Belknap was also notable for his restrained and honest treatment of controversial topics, including Native American relations and slavery, although his perspective remained largely shaped by the racial and cultural assumptions of his time.8 Nonetheless, his insistence on accuracy, documentation, and intellectual independence set a new standard for American historians, and his legacy endures in the archival and methodological practices he helped establish.

Hannah Adams (1755–1831)

Hannah Adams was a groundbreaking figure in early American intellectual history and one of the first professional female writers in the United States. Her contributions to historiography were both innovative and courageous, emerging at a time when few women had access to scholarly circles or publication opportunities. Best known for her A Summary History of New-England (1799) and her earlier A View of Religions (1784), Adams carved a unique space in historical writing through her impartial, comparative method and her meticulous attention to religious and cultural diversity.9 Trained informally by her father and largely self-educated, Adams developed a methodical and analytical approach to history that eschewed sectarian bias—an especially bold stance in the religiously charged atmosphere of post-Revolutionary New England.10 Her View of Religions, which cataloged and summarized global religious denominations with remarkable neutrality, was praised for its breadth and objectivity, and it challenged prevailing assumptions about both religious orthodoxy and women’s intellectual capabilities. In A Summary History, she extended her careful documentary approach to regional history, demonstrating the same commitment to accuracy, balance, and moral clarity that characterized her earlier work.

Adams’ role as a female historian in the early republic was profoundly shaped by both societal constraints and personal perseverance. Unlike many of her male contemporaries, she did not benefit from institutional affiliation or public office; instead, she relied on the patronage of sympathetic readers and literary societies, including the Massachusetts Historical Society, which granted her rare access to its archives.11 Her participation in that institution—at a time when women were largely excluded from formal intellectual life—was a quiet but powerful assertion of scholarly legitimacy. Adams also faced direct challenges to her work, most notably in a public dispute with Rev. Jedidiah Morse, who accused her of plagiarism despite her clear methodological independence.12 That controversy, while difficult, underscored the gendered terrain of early American letters, where female authors were often scrutinized more severely than their male peers. Yet Adams remained committed to historical inquiry and continued to publish throughout her life, contributing not only to historiography but also to the broader struggle for intellectual recognition of women. Her balanced tone, documentary rigor, and pioneering spirit make her a critical—if often overlooked—figure in the evolution of American historical thought.

Chronicling a Nation Growing

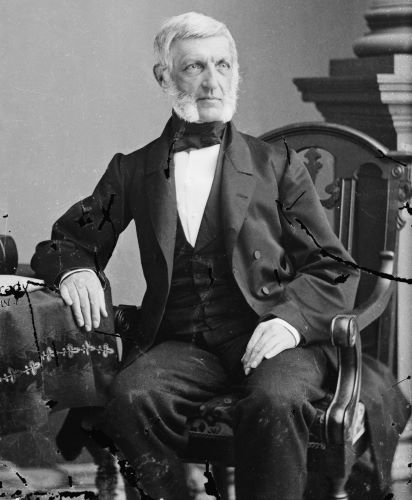

George Bancroft (1800-1891)

George Bancroft was one of the most prominent and influential American historians of the nineteenth century, widely regarded as the “father of American history” for his monumental and ideologically charged History of the United States, from the Discovery of the American Continent. A product of elite education, Bancroft studied at Harvard and later in Germany, where he absorbed the historical methods of German idealism, particularly the philosophies of Herder and Hegel.13 These influences shaped his vision of history as a purposeful, moral drama culminating in the progress of liberty and democratic self-government—an interpretation he applied to the American past with evangelical zeal. His multivolume work, first published in 1834 and expanded over the decades, presented the United States as the destined vehicle of human freedom, framing its origins and growth in near-sacred terms.14 Bancroft’s prose was rich, rhetorical, and often heroic, portraying historical actors as embodiments of grand moral principles. His portrayal of the Revolution, the Founding Fathers, and westward expansion cast the American project as not only historically inevitable but also divinely sanctioned—a teleological narrative aligned with the romantic nationalism of his era.

Despite its enduring influence, Bancroft’s historiography was not without significant limitations. His work was deeply shaped by a Whiggish framework, emphasizing linear progress and national unity while minimizing or ignoring internal conflict, dissenting voices, and the darker consequences of expansion and empire. He offered little critical reflection on slavery, Indigenous displacement, or the growing sectional divide that would culminate in civil war—realities that did not fit easily within his triumphant vision of national destiny.15 Moreover, Bancroft’s historical practice, though grand in scope, lacked the rigorous source criticism that would later characterize professional academic history. His legacy is therefore twofold: on the one hand, he elevated American historical writing to a level of national prestige and literary grandeur; on the other, he exemplified the mythmaking tendencies of nineteenth-century historiography, sacrificing complexity and conflict for coherence and purpose. Still, Bancroft’s influence was vast—shaping public understanding of American identity well into the twentieth century—and his efforts to enshrine the nation’s past in a sweeping, cohesive narrative established the foundation for both popular and professional historical discourse in the United States.

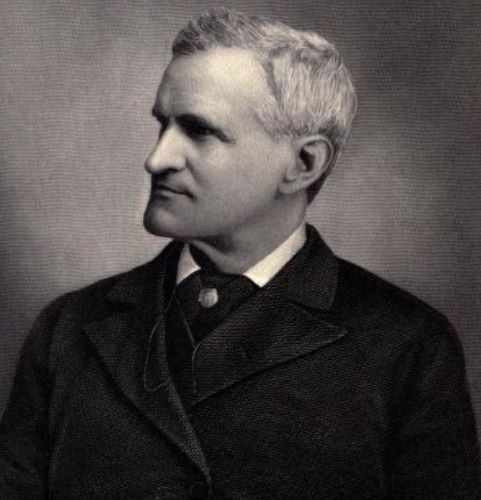

Francis Parkman (1823-1893)

Francis Parkman was one of the most celebrated narrative historians of the nineteenth century, renowned for his vivid prose and epic portrayals of colonial conflict in North America. Educated at Harvard and influenced by both romanticism and classical historiography, Parkman devoted his life to chronicling the struggle between France and Britain for dominance in the New World. His most acclaimed work, France and England in North America, a multi-volume series published between 1865 and 1892, offered a sweeping, dramatized account of imperial rivalry, frontier warfare, and cultural encounter.16 Parkman approached history as both literature and moral parable, bringing a novelist’s sensibility to the structure, pacing, and character development of his narratives. His portrayal of figures such as La Salle, Montcalm, and Wolfe imbued historical actors with dramatic intensity, casting their actions as part of a grand civilizational contest. At the same time, his rigorous use of archival sources, including documents from French and British repositories, marked a significant advancement in historical method, blending romantic style with empirical discipline.

Yet Parkman’s work also reveals the deep ideological and cultural biases of his time. While he admired aspects of Native American cultures, he largely viewed them through a lens of primitivism and racial hierarchy, often contrasting what he saw as the savage wilderness with the march of European progress and Christian civilization.17 His accounts of Indigenous peoples, particularly the Iroquois and Algonquins, were shaped by a belief in Anglo-American superiority and a sense of manifest destiny that echoed the dominant ideologies of the Gilded Age. Moreover, Parkman’s anti-Catholicism and occasional glorification of imperial conquest reflected broader Protestant, Anglo-Saxon anxieties about national identity and religious authority.18 Despite these ideological limitations, his narrative artistry, attention to detail, and pioneering archival work earned him enduring praise. Parkman’s legacy lies in his synthesis of history as both scholarly endeavor and literary achievement—his ability to animate the past while laying the groundwork for more critical and inclusive approaches in the century to follow.

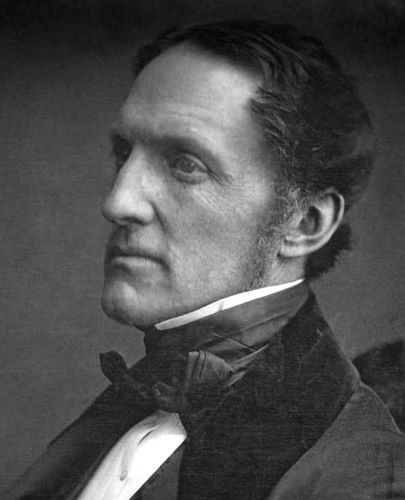

William H. Prescott (1796-1859)

William H. Prescott was a foundational figure in nineteenth-century American historiography, best known for his richly detailed and stylistically elegant histories of the Spanish Empire. Despite suffering from near-blindness throughout his adult life—a condition that forced him to rely on assistants and a noctograph for writing—Prescott produced monumental works that combined literary grace with scholarly rigor. His first major publication, History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella the Catholic (1837), was immediately acclaimed for its balance of narrative drive and critical analysis.19 Prescott followed this success with History of the Conquest of Mexico (1843) and History of the Conquest of Peru (1847), which cemented his reputation on both sides of the Atlantic. Drawing on a wide array of Spanish and Latin American sources, including manuscripts from the archives of Madrid and Seville, Prescott was among the first American historians to work with foreign-language primary materials on a large scale.20 His narrative voice was measured yet dramatic, evoking the grandeur and tragedy of empire while maintaining a commitment to factual fidelity and moral clarity. He treated history as both a literary and ethical pursuit, aiming not only to inform but also to elevate the reader through stories of heroism, ambition, and consequence.

However, Prescott’s legacy is also marked by the cultural assumptions and intellectual frameworks of his time. While he admired the achievements of the Aztecs and Incas and offered some critique of Spanish cruelty, his interpretation of conquest was still shaped by Eurocentric and romanticized notions of civilization and progress.21 Like his contemporary Francis Parkman, Prescott often framed indigenous societies as noble but ultimately doomed in the face of European superiority, reinforcing a teleological view of history aligned with nineteenth-century liberal imperialism. His work was less overtly nationalistic than George Bancroft’s, yet it still reflected an American fascination with empire and the moral drama of civilizational encounters. Moreover, Prescott’s method—though advanced for his era—was limited by the selectivity of his sources and the ideological filters through which he interpreted them. Nevertheless, his influence on the professionalization of American history writing was profound. He brought classical humanist sensibilities into dialogue with modern historiographical practice, setting a high standard for historical narrative that balanced scholarly depth with literary polish.

James Ford Rhodes (1848-1927)

James Ford Rhodes emerged as one of the leading historians of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, gaining national acclaim for his multivolume History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850, which chronicled the sectional crisis, Civil War, and Reconstruction from a Northern, conservative-liberal perspective.22 A wealthy industrialist turned self-taught historian, Rhodes brought a businessman’s efficiency and precision to historical writing. He drew extensively on government documents, speeches, newspapers, and private correspondence, and he was praised for the exhaustive nature of his research and his clear, direct prose. Rhodes’s historical philosophy emphasized causality and moral judgment, with slavery identified as the fundamental cause of the Civil War—a view that aligned with the postbellum Northern consensus.23 His work earned him the Pulitzer Prize in History in 1918 for Volume VII, which covered the presidency of Andrew Johnson, and it was widely used in both academic and popular settings throughout the early twentieth century. Though not formally trained in history, Rhodes’s writings were seen as authoritative and objective by his contemporaries, and his commitment to empiricism helped solidify the emerging standards of professional historiography in the United States.

However, Rhodes’s legacy has been subject to critical reassessment, especially concerning his treatment of Reconstruction and race. While he denounced slavery as morally abhorrent and supported the Union cause, he harbored deeply paternalistic and racially biased views that shaped his interpretation of postwar events. His depiction of African Americans during Reconstruction echoed the stereotypes common in the late nineteenth century, portraying Black political participation as inherently corrupt and incompetent, and thus contributing to the “Dunning School” narrative that justified white Southern redemption and disenfranchisement.24 Rhodes regarded the Fifteenth Amendment as a mistake and viewed Radical Republican policies as excessively punitive and destabilizing. These perspectives reflect the racial attitudes of his time and reveal the ideological underpinnings of what was often framed as objective analysis. Nevertheless, his rigorous documentation and accessible style influenced generations of historians, and his effort to write a comprehensive, source-based political history set an important precedent. Rhodes thus occupies a paradoxical position: a progressive in method, but conservative in outlook—an emblem of both the strengths and blind spots of early twentieth-century American historiography.

Conclusion

Early American historians played a crucial role in shaping the intellectual and cultural foundations of the fledgling republic. Writing in a period marked by revolution, nation-building, and expanding democratic ideals, these historians sought to craft narratives that not only recorded events but also legitimized the American experiment. Figures like David Ramsay, Mercy Otis Warren, and Jeremy Belknap brought Enlightenment principles, civic virtue, and moral purpose to their historical writing, offering interpretations that framed the Revolution and its aftermath as both rational and providential. Their works served as instruments of national identity, constructing a shared past that reinforced political ideals and unified diverse populations under the banner of republicanism. Yet their histories were also reflective of their limitations—excluding marginalized voices, simplifying complex social dynamics, and often privileging myth over messy truth. Despite these constraints, the efforts of early American historians laid the groundwork for a distinctly American historiography. They transformed historical writing from a colonial practice of record-keeping into a conscious act of nation-making, establishing the foundation upon which later generations of scholars would build, challenge, and revise the ever-evolving story of the United States.

Appendix

Endnotes

- David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: R. Aitken & Son, 1789).

- Lester H. Cohen, “David Ramsay and the Politics of Historical Writing in the New Republic,” William and Mary Quarterly 49, no. 4 (1992): 573–596.

- Rosemarie Zagarri, Revolutionary Backlash: Women and Politics in the Early American Republic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), 17–19.

- David Ramsay, The History of South Carolina, 2 vols. (Charleston: David Longworth, 1809), 205–207.

- Jeremy Belknap, The History of New Hampshire, 3 vols. (Boston: Isaiah Thomas and Ebenezer T. Andrews, 1784–1792).

- John R. Gillis, “Memory and Naming in the History of the American Nation,” History and Memory 5, no. 1 (1993): 112–135.

- Louis Leonard Tucker, Clio’s Consort: Jeremy Belknap and the Founding of the Massachusetts Historical Society (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1970), 14–19.

- Robert Gross, “Cultural Capital and the History of the Early Republic,” William and Mary Quarterly 48, no. 2 (1991): 170–172.

- Hannah Adams, A Summary History of New-England (Dedham, MA: H. Mann and J.H. Adams, 1799).

- Zabelle Stodola, A Woman’s Work Is Never Done: Women, Religion, and Reform in Antebellum New England (New York: Garland Publishing, 1991), 17–21.

- Mary Kelley, Learning to Stand and Speak: Women, Education, and Public Life in America’s Republic (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 102–105.

- Mary Sarah Bilder, “The Lost Lawyers: Early American Legal Literates and Transatlantic Legal Culture,” Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities 11, no. 1 (1999): 51–53.

- Robert D. Richardson Jr., The Rise of American Philosophy: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1860–1930 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1997), 52–53.

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, from the Discovery of the American Continent, 10 vols. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1834–1874).

- John Higham, History: Professional Scholarship in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983), 15–18.

- Francis Parkman, France and England in North America, 7 vols. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1865–1892).

- Richard White, “Frederick Jackson Turner and Buffalo Bill,” The American Historical Review 112, no. 4 (2007): 912–913.

- David Levin, History as Romantic Art: Bancroft, Prescott, Motley, and Parkman (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1959), 228–235.

- William H. Prescott, History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella the Catholic, 3 vols. (Boston: American Stationers’ Company, 1837).

- Cushing Strout, The Pragmatic Revolt in American History: Carl Becker and Charles Beard (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959), 18–20.

- Rolena Adorno, “The Colonial Origins of the Modern Mexican Historical Narrative,” A Companion to Latin American Literature and Culture, ed. Sara Castro-Klarén (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008), 70–72.

- James Ford Rhodes, History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850, 7 vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1893–1906).

- Michael Les Benedict, Preserving the Constitution: Essays on Politics and the Constitution in the Reconstruction Era (New York: Fordham University Press, 2006), 94–97.

- Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 608–610.

Bibliography

- Adams, Hannah. A Summary History of New-England. Dedham, MA: H. Mann and J.H. Adams, 1799.

- Adorno, Rolena. “The Colonial Origins of the Modern Mexican Historical Narrative.” In A Companion to Latin American Literature and Culture, edited by Sara Castro-Klarén, 66–77. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008.

- Bancroft, George. History of the United States, from the Discovery of the American Continent. 10 vols. Boston: Little, Brown, 1834–1874.

- Belknap, Jeremy. The History of New Hampshire. 3 vols. Boston: Isaiah Thomas and Ebenezer T. Andrews, 1784–1792.

- Benedict, Michael Les. Preserving the Constitution: Essays on Politics and the Constitution in the Reconstruction Era. New York: Fordham University Press, 2006.

- Bilder, Mary Sarah. “The Lost Lawyers: Early American Legal Literates and Transatlantic Legal Culture.” Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities 11, no. 1 (1999): 47–104.

- Cohen, Lester H. “David Ramsay and the Politics of Historical Writing in the New Republic.” William and Mary Quarterly 49, no. 4 (1992): 573–596.

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

- Gillis, John R. “Memory and Naming in the History of the American Nation.” History and Memory 5, no. 1 (1993): 112–135.

- Gross, Robert. “Cultural Capital and the History of the Early Republic.” William and Mary Quarterly 48, no. 2 (1991): 170–172.

- Higham, John. History: Professional Scholarship in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983.

- Kelley, Mary. Learning to Stand and Speak: Women, Education, and Public Life in America’s Republic. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- Levin, David. History as Romantic Art: Bancroft, Prescott, Motley, and Parkman. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1959.

- Parkman, Francis. France and England in North America. 7 vols. Boston: Little, Brown, 1865–1892.

- Prescott, William H. History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella the Catholic. 3 vols. Boston: American Stationers’ Company, 1837.

- Ramsay, David. The History of the American Revolution. 2 vols. Philadelphia: R. Aitken & Son, 1789.

- ———. The History of South Carolina. 2 vols. Charleston: David Longworth, 1809.

- Rhodes, James Ford. History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850. 7 vols. New York: Macmillan, 1893–1906.

- Richardson, Robert D., Jr. The Rise of American Philosophy: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1860–1930. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1997.

- Stodola, Zabelle. A Woman’s Work Is Never Done: Women, Religion, and Reform in Antebellum New England. New York: Garland Publishing, 1991.

- Strout, Cushing. The Pragmatic Revolt in American History: Carl Becker and Charles Beard. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959.

- Tucker, Louis Leonard. Clio’s Consort: Jeremy Belknap and the Founding of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1970.

- White, Richard. “Frederick Jackson Turner and Buffalo Bill.” The American Historical Review 112, no. 4 (2007): 851–872.

- Zagarri, Rosemarie. Revolutionary Backlash: Women and Politics in the Early American Republic. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.18.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.