The dead did not vanish but were transformed.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Across the high plains of the Andes, the dense jungles of the Yucatán, and the imperial heart of the Valley of Mexico, three great civilizations carved their place into the stone and soil of the ancient Americas. The Inca, Maya, and Aztec empires—each distinct in language, architecture, and political order—nonetheless shared a profound and unyielding preoccupation with death. To them, death was no mere terminus, no simple cessation of breath, but a threshold to realms more enduring than flesh, governed by gods, stars, ancestors, and the sacred rhythms of the cosmos. Their rituals for the dead were acts of cosmic diplomacy, entwining the destinies of the living with those of the departed, and anchoring empires in metaphysical continuity.

This study journeys into the ceremonial and symbolic heart of these ancient cultures, where the dead did not vanish but were transformed—into ancestors, divine emissaries, and celestial travelers. It explores the funerary rites of Inca nobility whose mummies walked among the living; the intricate Maya conception of the soul’s descent into the watery underworld of Xibalba; and the blood-soaked Aztec sacrifices that fed the sun and sustained the world. Each tradition, in its own way, sought to negotiate the terror and transcendence of death through ritual, architecture, and myth.

What emerges is not merely a catalog of funerary customs, but a comparative portrait of civilizations that saw in death the possibility of permanence—an ember that, if properly tended through rite and reverence, could burn beyond mortality. In the interplay between ritual and belief, body and cosmos, the Inca, Maya, and Aztec peoples fashioned sacred worlds where the dead were not lost, but lit the way forward.

Veil of the Xibalban Twilight: Death and Ritual in the Maya World

Overview

To the ancient Maya, death was not an extinguishing of light, but a descent into shadow—a perilous, sacred passage into the underworld realm of Xibalba, where the soul’s fate hung in the balance. Far from a final rupture, death in Maya cosmology constituted a liminal state, a threshold between worlds and a critical moment in the cyclical rhythms of time, kingship, and cosmic renewal. The funerary practices and death rituals of the Maya—expressed through elaborate tombs, intricate mythology, ritual art, and calendrical precision—reveal a civilization deeply attuned to the spiritual topography of mortality.

This essay explores the central themes and practices of Maya death rituals: the journey through Xibalba; the roles of kings, ancestors, and gods; the physical preparation of the dead; and the ceremonial logic by which the Maya sought not only to understand death, but to manipulate its power and preserve the eternal balance of the cosmos.

The Cosmology of Death: Life as Cycle, Death as Passage

In the worldview of the ancient Maya, death was not an end but a critical transition in a grand cosmic cycle. Life and death were interwoven aspects of an eternal process, governed not by a linear progression of time, but by cyclical recurrence and divine orchestration. The Maya conceived of the cosmos as a three-tiered structure: the heavens above, the earthly plane in the middle, and the watery underworld, known as Xibalba, below. Each of these realms was populated by gods and spirits, and each played a vital role in shaping both existence and the afterlife. This cosmology framed death as a journey into another phase of being, with the soul traversing dangerous spiritual terrains before either being reborn or integrated into the ancestral world. Such a vision marked a departure from the binary moral categories of salvation and damnation found in later Western religious thought and emphasized instead the natural rhythm of transformation and return.1

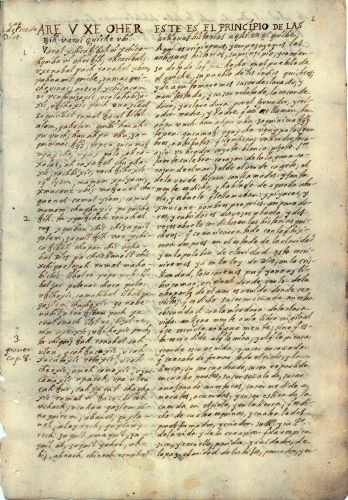

The mythological narrative that most powerfully encodes this cosmology is the Popol Vuh, the K’iche’ Maya creation epic. At its heart is the tale of the Hero Twins, Hunahpu and Xbalanque, who descend into Xibalba to confront the Lords of Death. Through cunning and divine favor, they defeat the powers of the underworld and are transformed into celestial bodies—the sun and the moon. This myth served not merely as entertainment or moral instruction but as a metaphysical blueprint. The journey of the Hero Twins reflected the soul’s path after death and informed the funerary and sacrificial practices of the Maya elite. Kings, in particular, often staged their deaths as reenactments of the Hero Twins’ descent, signaling their transformation from mortal rulers into divine ancestors and cosmic intercessors.2 Their sarcophagi, tomb art, and hieroglyphic texts reinforced this mythic script, providing visual and textual guides for the soul’s journey through death to apotheosis.

For ordinary Maya as well, death was part of a sacred continuum rooted in the agricultural and calendrical cycles that governed daily life. The planting and harvesting of maize—the central sacred crop—was ritually paralleled with human life and death. Just as maize kernels were buried in the earth to be reborn in the rainy season, so too were human bodies interred in the soil to await spiritual renewal. This association is vividly depicted in Maya iconography, such as the maize god emerging from a turtle shell (symbolizing the earth), evoking rebirth from the underworld.3 The burial of individuals beneath family homes further symbolized this integration, keeping ancestors physically close and spiritually active within the domestic sphere. These practices emphasized death not as exile but as rootedness—a return to the sustaining source of life, both literal and mythic.

Maya afterlife beliefs did not promise a universal paradise but instead described a variegated spiritual geography. The soul’s destination and experience were shaped by the manner of death rather than moral conduct. Warriors who died in battle, women who died in childbirth, and those sacrificed in rituals were believed to ascend directly to the heavens, joining the sun and stars. Others, particularly those who died of illness or old age, entered Xibalba, a dark and dangerous underworld filled with trials. Yet even Xibalba was not a place of eternal punishment—it was a realm of transformation, fertility, and renewal. Navigating it successfully did not depend solely on one’s actions in life but on proper funerary rites, offerings, and spiritual assistance, including spirit companions like dogs, which were often buried alongside the deceased to serve as guides.4 The underworld thus embodied not condemnation but necessity: a site of struggle, yes, but also of cosmic purpose.

These cosmological ideas persisted even after the Spanish conquest, subtly surviving beneath the surface of imposed Catholic doctrine. In modern Maya communities, vestiges of ancient death rituals continue in the form of Day of the Dead celebrations, household altars, and agricultural ceremonies dedicated to ancestors. The ancient notion that the dead dwell among the living, guiding and sustaining them, remains central to Maya spirituality. This continuity underscores the resilience of a worldview in which life and death are not opposites, but reflections—where each death is a return, each burial a planting, and each passage through darkness a step toward renewal. In the Maya cosmos, death is not feared as final, but revered as essential, reminding us that to die is to rejoin the cycle from which all life flows.5

Royal Death: Tombs, Sacral Kingship, and Apotheosis

Among the ancient Maya, kingship was not merely a political institution—it was a sacred vocation embedded within the divine structure of the cosmos. The ruler, or k’uhul ajaw (“holy lord”), was considered the earthly manifestation of divine authority and the living axis between gods, ancestors, and people. His death, therefore, was not a disappearance but a transformation, an act of cosmic reintegration. Maya royal funerary practices reflected this understanding by staging death as a rite of apotheosis. The tomb was not simply a resting place—it was a stage upon which the final sacred drama of kingship unfolded, wherein the deceased lord ascended (or descended) into the divine realms to become an ancestor-god. This theological framing of death reinforced dynastic continuity and sacral authority, as the dead king was believed to intercede from the spirit world and sustain the legitimacy of his successors.6

The structure and symbolism of royal tombs embodied these cosmological ideas with precision. Typically located deep within pyramid-temples—architectural metaphors for the sacred mountain or Witz—tombs were built to evoke the cave, the underworld, and the womb. This spatial orientation reflected the mythic journey of the maize god, who was buried in the earth and reborn in glory. In Palenque, the tomb of K’inich Janaab’ Pakal, one of the most famous Maya rulers, illustrates this cosmological theatre. Discovered in the Temple of the Inscriptions, his sarcophagus lies at the base of a long staircase, symbolizing descent into Xibalba. The lid of the sarcophagus is intricately carved with an image of Pakal poised between the jaws of the underworld and the World Tree, signifying his apotheosis and ascent into the celestial sphere.7 Far from portraying decay, the tomb architecture and iconography emphasized transformation—death as divinization.

Burial goods further reinforced the sacred status of the deceased king. Rulers were interred with jade masks (symbolizing breath and divine essence), elaborate headdresses, scepters, stingray spines used in bloodletting rituals, and items of cosmological symbolism such as shells, obsidian blades, and miniature effigies of gods. These offerings were not ornamental—they were tools and markers of divine identity, aiding the ruler in his journey through the underworld and his elevation among the gods. In some cases, human sacrifices were included, likely intended as attendants in the afterlife or as ritualized captives fulfilling martial obligations. The funerary ensemble served to reinforce the king’s role not only in life but in perpetuity, reestablishing his connection to the cosmos even in death.8 Through these carefully curated symbols, the deceased was transformed into a potent ancestor spirit (wayob)—a force not lost to time, but active in the maintenance of divine order.

The performance of royal funerary rites was also a public reaffirmation of power. These ceremonies often coincided with calendrical events and were recorded in stone inscriptions, stelae, and codices, preserving not only the death but the transformation of the ruler as mythic narrative. His life and deeds were retroactively inscribed into sacred time, aligning his personal biography with cosmic cycles. In Copán, for example, the death of Waxaklajun Ubaah K’awiil (18 Rabbit) and the construction of his tomb beneath Temple 16 were framed within a broader program of dynastic monumentality. Successor kings invoked his apotheosis to reinforce their own legitimacy, using the image of the divinized ancestor as a symbol of political and cosmic continuity.9 Thus, death did not diminish royal authority—it transfigured it, embedding it deeper into the metaphysical structure of Maya kingship.

This integration of royal death into theology, architecture, and political ritual underscores the profound interdependence of sacred and secular power in Maya civilization. The king’s body became a symbolic site—his tomb a conduit between worlds, his death a regenerative sacrifice, and his memory a source of legitimacy for generations. Through this sacralization of death, Maya kingship achieved a kind of temporal elasticity: the ruler, though physically gone, remained spiritually present, accessible through ritual and inscription. In such a cosmology, death was not absence but amplification—a luminous emergence into the cosmic order from which the sacred majesty of kings was perpetually drawn.10

Mortuary Practices among the Common Maya

While the royal and elite funerary traditions of the ancient Maya have captured scholarly attention for their monumental scale and ideological significance, the mortuary practices of commoners offer an equally vital, though more modest, window into Maya cosmology and social life. Far from being uniform or simplistic, commoner burials were shaped by localized traditions, community identity, and the household’s position within the broader sacred landscape. Most non-elite Maya were buried in or near their homes, often beneath the floors of domestic structures or within the patios of family compounds. This intramural burial practice reflected a deeply rooted belief in the enduring presence of ancestors within the daily rhythms of life, not as abstract spirits but as active members of the living lineage.11 The dead were not exiled to distant necropolises but kept close, reinforcing familial continuity and spiritual proximity across generations.

The preparation of the body itself followed ritual patterns that mirrored the cosmological understanding of death as a return to origin. Bodies were typically placed in a crouched or fetal position, oriented toward specific cardinal directions depending on local customs and time period. This fetal posture symbolized the return to the womb of Pachamama—in Maya terms, the Earth Mother—and signified that death was not an ending but a regeneration. The grave was often lined or covered with stones, pottery sherds, or plaster, and in some cases, contained charcoal or cinnabar, suggesting symbolic purification or transformation.12 Grave goods, though less opulent than those of elite tombs, were still thoughtfully selected: ceramic vessels, spindle whorls, obsidian blades, food offerings, personal ornaments, and occasionally miniature figurines. These objects were not merely sentimental—they were functional, intended to provide the deceased with the necessities for the journey through the underworld, or to serve as symbols of identity, occupation, and spiritual affiliation.

In some instances, dogs—particularly the native Xoloitzcuintli—were buried alongside the dead, echoing beliefs held more broadly in Mesoamerica about canine psychopomps who guided souls through the dangers of the underworld. The presence of these animals in commoner graves, as well as in elite contexts, speaks to a widely held metaphysical understanding that cut across class lines. In contrast to hierarchical religious doctrines that reserved the sacred for the elite, Maya mortuary practices suggest a democratization of cosmological belief: even the humblest members of society participated in a spiritual framework that dignified death and envisioned an active afterlife.13 This belief also animated the ongoing care of the dead. Periodic offerings of food, drink, incense, and even blood were made at burial sites, which were often maintained as domestic shrines. These rituals not only honored the deceased but renewed the covenant between living and dead—ensuring protection, fertility, and ancestral favor.

Archaeological evidence also points to more dynamic post-burial relationships with the dead. In some cases, bones were exhumed, curated, and reburied, or incorporated into household altars and ritual caches. Skulls and long bones might be painted or displayed, and in certain contexts, these remains were treated as relics that conferred spiritual power on the household.14 These practices indicate that mortuary rites extended well beyond the moment of death, developing into long-term cycles of veneration. The household thus became both a spatial and spiritual unit, with the living and the dead occupying mutually sustaining roles. This arrangement parallels broader Maya concepts of cyclical time, in which past and present were never strictly divided but folded into each other through ritual and memory. In this sense, the common Maya dead were not passive recipients of ritual attention but ongoing agents within the cosmological and social order.

While the grandeur of elite tombs may appear more overtly theatrical, the mortuary practices of commoners were no less spiritually meaningful. These rites preserved ancestral memory, bound the household to the land, and encoded theological beliefs into the very foundations of domestic life. In the absence of monumental architecture, commoner families created sacred space beneath their feet. The persistence of these practices into the Postclassic and even colonial periods—albeit syncretized with Christian elements—attests to their deep cultural resilience.15 For the common Maya, death was not a rupture from the world but a relocation within it: from the center of the hearth to the heart of the earth, from the breath of life to the soil of renewal.

Human Sacrifice and Death as Offering

Human sacrifice among the ancient Maya was not an aberration of cruelty or superstition, but a ritual expression of cosmic reciprocity. In their theological worldview, the gods had themselves suffered and bled to create the world and sustain the cycles of nature; thus, human beings were bound by sacred obligation to reciprocate. Blood, considered the most potent form of life essence (k’uh), was the medium through which this reciprocal relationship was maintained. While bloodletting by elites—through piercing ears, tongues, or genitals—was a common form of devotion, human sacrifice occupied a higher ritual plane, reserved for exceptional ceremonies, calendrical rites, and crises such as droughts or political instability. These sacrificial acts were neither random nor savage—they were deliberate offerings meant to nourish the gods, restore cosmic balance, and ensure agricultural fertility and celestial order.16

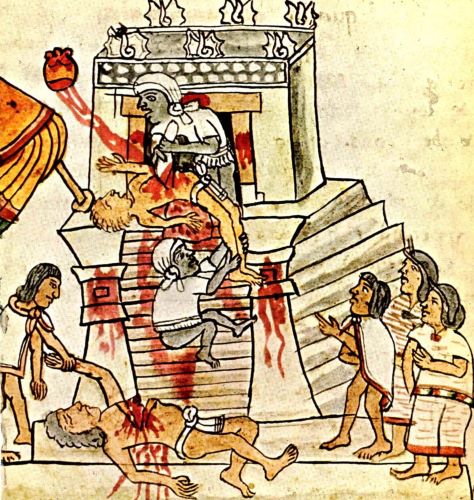

The act of sacrifice often took place in ceremonial centers atop pyramidal temples, transforming the built environment into sacred stages of cosmogenesis. The Popol Vuh narrates how the Hero Twins defeated the lords of the underworld through a sacrificial act of self-transcendence, a myth that framed human sacrifice as not merely death, but transformation. Victims—often war captives, but sometimes members of the community chosen for their purity or symbolic resonance—were treated as living embodiments of gods. Their deaths were ritual performances meant to mirror and re-enact divine myth. In some contexts, they were given ritual names and garb matching specific deities, highlighting their temporary elevation to divine status.17 Their hearts were sometimes extracted and offered to the sun, or their blood used to sanctify altars, maize fields, or idols. Far from acts of violence for its own sake, these sacrifices were understood as vital offerings that sustained the balance between the human and divine worlds.

The methods of sacrifice varied by region, occasion, and theological purpose. The most iconic method, heart extraction, involved the laying of the victim upon a stone altar, where the chest was cut open—likely with obsidian blades—to remove the still-beating heart. This act was performed by trained ritual specialists, often in public, before assembled elites and community members. Decapitation was another frequent method, associated especially with rain and fertility gods. Archaeological findings at sites like Chichen Itzá’s Sacred Cenote reveal that victims were sometimes cast into wells as offerings to Chaac, the rain god, particularly during times of drought.18 Other sacrificial rituals included dismemberment, burning, and ritual combat, where prisoners were forced to fight as gladiators against elite warriors. In each of these cases, death was not random but symbolically loaded—each form of killing matched a specific ritual logic rooted in myth, agricultural need, or divine imitation.

Children were sometimes selected for sacrifice, a practice shared with other Mesoamerican cultures but deeply imbued with Maya cosmology. Young boys and girls, considered untainted and spiritually powerful, were offered during rain ceremonies, agricultural festivals, and to placate angry or neglected deities. Their tears were believed to bring rain, their innocence acting as a pure conduit for divine communication. This was not viewed by the Maya as an act of brutality but as the highest form of spiritual gift—a gesture of selflessness and cosmic necessity.19 These sacrifices were not done lightly. They were theologically justified, ritually prepared, and socially sanctioned through collective memory and mythic precedent. Indeed, in Maya theology, death in sacrifice was not an end but a transformation—into a divine intercessor, an ancestral presence, or even a celestial body.

Ultimately, human sacrifice among the Maya reveals a culture in which death was imbued with purpose, framed not by horror but by sacrality. The sacrifice was a metaphysical transaction, a necessary rupture that maintained the flow of cosmic energy. The dead were not lost but consecrated, their blood woven into the fabric of creation itself. While modern sensibilities recoil at the violence of such acts, to the Maya, sacrifice was both a theological truth and a political tool—confirming elite power, sanctifying time, and sustaining life itself. In this way, the Maya joined many other ancient civilizations in ritualizing death not to glorify mortality, but to give it cosmic utility—to make of human death an offering not of despair, but of divine continuation.20

Ritual Continuity and the Legacy of Maya Death Beliefs

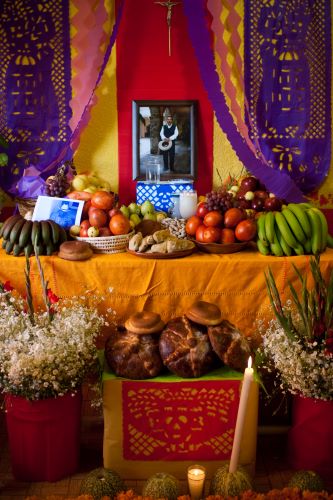

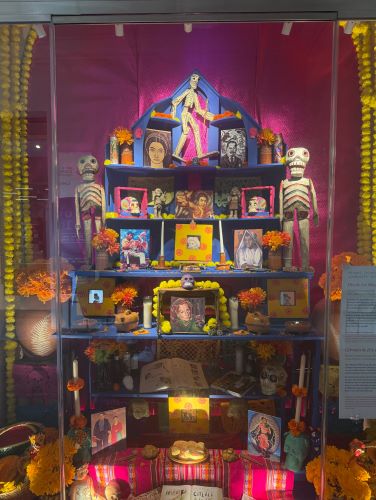

Despite the devastating disruption caused by Spanish colonization in the sixteenth century, Maya beliefs about death did not vanish; they evolved. Colonial authorities and Christian missionaries aggressively targeted indigenous mortuary customs, labeling them idolatrous and demonic. Nonetheless, the theological foundations of Maya death rituals proved resilient, adapting to survive beneath and within Catholic structures. Indigenous communities reinterpreted ancestral veneration through the lens of saints and Christian holidays, syncretizing their ancient cosmology with imposed doctrines. Particularly powerful was the adaptation of the Day of the Dead—now celebrated in early November and aligned with All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days—which became a socially accepted context for the continuation of pre-Hispanic rituals honoring the dead.21 Beneath the iconography of crosses and saints lay older patterns: food offerings, incense burning, altars within homes, and the belief that the dead return to commune with the living.

In many modern Maya communities, such as those in the highlands of Guatemala and Chiapas, these ancestral practices remain central to daily life. Household altars are common, often featuring photographs or relics of deceased family members, adorned with candles, flowers (especially marigolds), and food. Families speak to the dead, offer prayers, and share meals with them during festival times, gestures that mirror the ancient belief that the ancestors are both spiritually present and socially active. Burial locations also echo pre-Columbian preferences: while modern cemeteries may be used, burials near or around the home persist in more rural areas, sustaining the physical and spiritual intimacy between the living and the departed.22 These practices maintain the core tenet of Maya mortuary ideology—that death is not separation but a transformation of presence, and that the dead continue to shape the well-being of the living.

The cosmological symbolism surrounding death has also persisted in the ceremonial calendar and ritual landscape. In agricultural festivals, particularly those associated with planting and harvest, offerings are still made to ancestral spirits believed to inhabit mountains, caves, and other sacred sites. These rituals—often performed by community ritual specialists or ajq’ijab’—retain elements of the old tripartite cosmology: the earth as the body of the maize god, caves as entrances to the underworld, and mountaintops as places of divine communion. In these liminal zones, the boundaries between life and death, earth and spirit, continue to blur.23 Offerings of copal incense, alcohol, and food remain central to these ceremonies, reinforcing the view that spiritual nourishment and reciprocity are still essential to maintaining balance between worlds. Through such rites, the ancient logic of death as a generative and sustaining force endures, woven into contemporary Maya lifeways.

Perhaps most remarkably, contemporary Maya communities continue to hold conceptual frameworks that recall ancient afterlife beliefs. While some now articulate their views within a Christian eschatological vocabulary—speaking of heaven, hell, or purgatory—many still speak of the soul’s journey, of ancestors who “return” or dwell in specific landscapes, and of the importance of proper ritual care for the dead. The use of spiritual guides, dreams as mediums of communication with ancestors, and the maintenance of ritual obligations to the dead all reflect enduring ideas of the afterlife as interactive and localized rather than abstract and distant.24 These beliefs are less a survival of ancient religion than a living adaptation, in which Maya communities assert agency by reshaping the imposed Catholic framework to reflect their ancestral cosmology. In this way, Maya death beliefs persist not only through continuity but through creative resistance.

The legacy of Maya death rituals also lives on in artistic, linguistic, and scholarly expressions. Glyphs and iconography found on stelae, ceramics, and codices continue to be studied, remembered, and reinterpreted by modern Maya intellectuals and activists reclaiming cultural identity. The revival of traditional languages, ceremonies, and mortuary customs is part of a broader decolonial project in which the past is not buried but revitalized. Maya conceptions of death—as cyclical, reciprocal, and communal—offer a profound alternative to modern, often individualistic and linear models of mortality.25 In honoring the dead not merely as memory but as presence, and in viewing death not as an end but as a phase of cosmic movement, contemporary Maya cultures affirm that the spiritual grammar of their ancestors still speaks, still breathes, and still guides.

Conclusion: Death as the Root of Cosmos

The death rituals of the ancient Maya were not the rites of a people resigned to oblivion but of a civilization that saw death as a mirror of life and a key to transcendence. Through myth, ritual, and sacred architecture, the Maya created a symbolic grammar in which death could be interpreted, honored, and even overcome. Whether buried beneath a household hearth or within the stone heart of a pyramid, the dead were never truly gone—they remained within the folds of time, curled in the earth’s memory, watching and waiting beneath the breath of Xibalba.

To study these rituals is to walk alongside the dead—not into darkness, but into the textured twilight where myth and memory burn with the quiet embers of eternity.

To Feed the Gods: Death and Ritual in the Aztec World

Overview

To the Aztecs—who called themselves Mexica—death was not the end of life, but its necessary counterpart, its twin and its sustainer. The world, they believed, was built upon death: death of gods, death of suns, death of men. From the bones of earlier worlds and the blood of sacrificed deities, the current age emerged. Thus, to live was to owe a debt, and to die was to pay it. No ancient civilization was more entangled with death, more dependent upon its ritual enactment, or more transfixed by its cosmic necessity than the Aztecs. To understand the Mexica world is to understand that death was not simply a biological reality, but the central axis of their spiritual and social order.

This essay explores the complex tapestry of Aztec death rituals, examining the mythology that underpinned their practices, the ceremonies that accompanied dying and burial, the fates of different souls in the afterlife, the symbolic economy of sacrifice, and the echoes of these beliefs in the post-conquest cultural world. In so doing, it offers a portrait of a civilization where death was not an interruption of life—but the condition of its possibility.

Myth and Metaphysics: The Divine Origins of Death

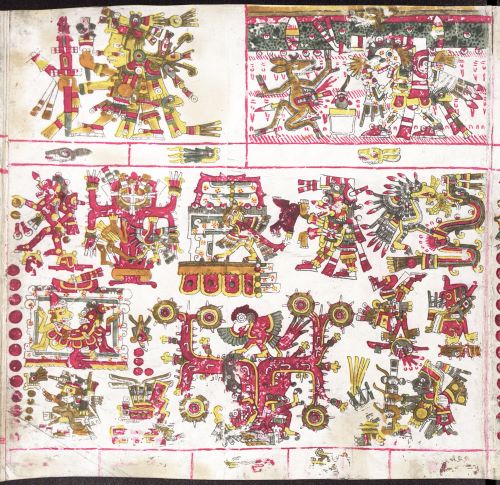

The Aztec conception of death was profoundly mythological and metaphysical, embedded in an intricate cosmogony where death was not a flaw in creation but its very foundation. According to Aztec myth, the world had passed through four previous ages—each destroyed by cataclysm—before the current “Fifth Sun” (Nahui Ollin) came into being. The Fifth Sun, which governed the present age, was not born naturally but through an act of divine self-sacrifice. In the sacred narrative recounted in the Codex Chimalpopoca and later colonial texts, the gods gathered in Teotihuacan and decided that one among them must immolate himself to become the new sun. The humble, diseased deity Nanahuatzin threw himself into the fire, followed by the more aristocratic Tecuciztecatl, and from Nanahuatzin’s ashes rose the sun. Yet this new sun would not move until the wind god Ehecatl offered his own blood and set the celestial body in motion.26 From its very inception, then, the cosmos required sacrifice—both divine and human—for its continuation.

This myth laid the metaphysical groundwork for the Aztec obsession with ritual death and sacrifice. The gods themselves had modeled the ideal behavior: to sustain the universe, they had voluntarily died. Thus, human beings, as creations of the gods and inheritors of the cosmic debt (tequitl), were obligated to offer their own blood and lives in return. This mutual obligation between gods and mortals was not viewed as tragic but as necessary, even noble. The metaphysical principle behind this was tlamictiliztli—”death as debt-payment”—a ritual act that sustained the cycles of time, nature, and divine favor. It followed that the more exalted the offering, the more potent its metaphysical value. Human sacrifice, especially when performed with ceremonial precision and cosmic alignment, was thus a continuation of divine will, not a deviation from it.27 The Aztec universe, unlike the linear salvation narratives of Christianity, was a web of reciprocity: gods fed men with creation, and men fed gods with blood.

At the heart of this metaphysical system was the belief that different gods presided over different types of death, and each form of death facilitated the balance of specific cosmic forces. Huitzilopochtli, the patron god of the sun and war, required the hearts of warriors to maintain the sun’s daily journey through the sky and underworld. Tlaloc, the rain god, demanded victims who died by drowning or diseases related to water. The goddess Cihuacoatl was associated with women who died in childbirth—believed to have perished in battle and honored as spiritual warriors.28 These categorizations were not simply theological—they structured Aztec social organization, ceremonial calendars, and even warfare. The infamous “flower wars” (xochiyaoyotl) fought against neighboring states were not primarily for territory but for captives, specifically to procure suitable victims for sacrifice. Such military engagements had both political and metaphysical aims: to maintain regional dominance and feed the gods with ritually appropriate deaths.

These divine narratives also influenced the Aztecs’ conceptualization of time and eschatology. The tonalpohualli (260-day ritual calendar) and xiuhpohualli (365-day solar calendar) were filled with festivals marking key points in the cosmic cycle, each requiring blood offerings to ensure the proper movement of the heavens and the fertility of the earth. The New Fire Ceremony, conducted every 52 years when the two calendars aligned, was the most dramatic affirmation of this worldview. During this liminal moment, all fires across the empire were extinguished, symbolizing the potential end of the world. Priests would then sacrifice a human victim, and from his chest cavity—ignited as a new hearth—sacred fire was distributed throughout the land.29 This ritual encapsulated the metaphysical belief that death is not destruction but regeneration, that only through blood could cosmic order be rekindled. The fire in the human heart quite literally rekindled the life of the world.

Ultimately, Aztec metaphysics viewed death as a principle of divine energy, a regenerative force rather than a negation. While many ancient civilizations linked death with judgment or punishment, the Aztecs saw it as ontological necessity—essential to maintaining the movement of the sun, the fertility of maize, and the balance of elemental powers. Even after the Spanish conquest, echoes of these beliefs remained embedded in cultural practices, including Día de los Muertos, which integrates pre-Hispanic notions of death with Catholic doctrine. In Aztec metaphysics, death is not the end of life but the consecration of it: the sacred offering that turns blood into sun, heart into fire, and corpse into cosmos.30 In this sense, the divine origins of death are not merely theological abstractions—they are the vital grammar through which the Aztecs understood their world, their obligations, and their destiny.

The Fate of the Dead: Aztec Afterlife Beliefs

Aztec conceptions of the afterlife diverged sharply from the moral dualism of Christian eschatology. Unlike the later European binary of heaven and hell, the Aztec dead were not judged by the ethical quality of their lives, but by the manner of their death. It was death itself—not life—that determined the soul’s destination. This belief stemmed from a metaphysical understanding that the world was upheld by cycles of death and regeneration, and that particular deaths aligned the deceased with specific deities and cosmic realms. The Aztec afterlife was not one but many: a stratified and multivalent geography of spiritual destinations, each governed by a deity and marked by its own symbolism, requirements, and significance.31

The highest honor was to die in sacrifice or in battle, which ensured the soul’s ascent to Tonatiuhichan, the house of the sun. There, the souls of slain warriors accompanied the sun on its daily journey across the sky. For four years, they would rise each morning in the east as hummingbirds or butterflies and follow the solar deity, Tonatiuh, across the heavens, only to vanish in the west and repeat the cycle. Women who died in childbirth were believed to undergo a parallel transformation: they joined the sun at its zenith and then accompanied it into the underworld. These cihuateteo—”divine women”—were considered fierce and liminal beings, often invoked in rites concerning fertility and danger. In both cases, death in service of cosmic order conferred immediate elevation and partial deification.32 These privileged dead were not mourned in sorrow but celebrated as protectors and participants in celestial power.

Another significant afterlife realm was Tlalocan, a lush and verdant paradise governed by the rain god Tlaloc. Unlike the martial afterlives of warriors and birthing women, Tlalocan was the destination for those who died by water-related causes: drowning, lightning strikes, or diseases associated with humidity and water. This realm was not one of struggle but of ease, a kind of spiritual Eden. There, the dead lived amid eternal spring, abundance, and fertility. Tlalocan stood in direct contrast to Mictlan, the most populous realm of the dead, ruled by Mictlantecuhtli and Mictecacihuatl. Mictlan was reserved for those who died ordinary deaths—by illness, old age, or unremarkable means. Entry into Mictlan required a perilous four-year journey through nine levels of trials: mountains that crushed travelers, icy winds, obsidian fields, and rivers of blood. The soul, often aided by a spirit dog, had to persevere through each stage to reach final rest.33

Yet Mictlan was not a place of punishment. It lacked the moral overtones of Christian hell and was instead a necessary phase of the soul’s transformation and eventual rest. In this vision, the soul’s task after death was not to account for its moral behavior but to navigate metaphysical obstacles. The trials of Mictlan echoed the broader Aztec philosophy that endurance through hardship—whether in life or death—was essential to maintaining one’s place within the cosmic order. Rituals performed by the living could assist the dead in this journey: offerings of food, incense, and sometimes dogs were buried with the deceased to provide spiritual nourishment and aid. These practices extended the principle of reciprocity into the afterlife; just as the living needed the favor of the dead, the dead needed the ritual care of the living to reach their final destination.34

The Aztec understanding of death as a multivalent phenomenon—categorically shaped by cosmology, not morality—underscores their distinctive spiritual worldview. Death was not a single fate, but a spectrum of possibilities, each aligned with elemental forces, divine personalities, and ritual obligations. The dead were not passive but continued to play vital roles within society—as protectors, ancestral intermediaries, or even threats if not properly honored. These afterlife beliefs reinforced the logic of sacrifice, the importance of death rituals, and the integration of mortuary practices into everyday life. In this way, the fate of the dead was never truly sealed by death itself—it was carried forward by memory, ritual, and the cosmic narrative into which each death was woven.35

Burial Customs and Funerary Practices

The mortuary practices of the Aztec were rich in symbolism, structured by cosmological principles, and varied according to social status, occupation, and manner of death. Burial was not a perfunctory conclusion to life but a ritual process intended to ensure the soul’s safe passage through the afterlife and proper integration into the cosmic order. The preparation of the body involved washing, adorning, and positioning the corpse in accordance with its destination in the afterlife. Those destined for Mictlan, the underworld of the ordinary dead, were typically cremated, and their ashes placed in funerary urns or buried with grave goods that would assist in the soul’s arduous journey through its nine levels. Accompanying items often included obsidian blades, food, water, clothing, and most notably, a dog—usually a Xoloitzcuintli—believed to guide the soul across the underworld’s river.36 This ritual economy of provision reflected the Aztec belief that death was a journey, not a resting state.

Funerary customs also varied significantly based on the type of death. Those who died in battle or childbirth were often buried rather than cremated, as their souls did not descend to Mictlan but ascended directly to the sun or joined divine forces. Their graves were considered spiritually potent and were sometimes marked with protective symbols. For infants and young children, the practices were distinct again: children who died young were believed to go to Chichihuacuauhco, a paradisiacal place nourished by a cosmic milk tree, where they awaited reincarnation. These young souls were often buried with toys, rattles, or tiny ceramic vessels, reflecting the belief in their eventual return to earthly life.37 The specificity and nuance of these practices demonstrate the Aztec commitment to aligning death rituals with the soul’s perceived trajectory and theological purpose.

Elite funerary rituals were considerably more elaborate, serving both spiritual and political functions. High-ranking nobles, priests, and rulers were cremated or interred with rich offerings, including jade, turquoise, feathered garments, and finely crafted ritual objects. Their remains might be stored in temple precincts, within pyramidal platforms, or near sacred caves considered portals to the underworld. For emperors such as Moctezuma and Itzcoatl, the funerary process was deeply ceremonial and involved public displays of mourning, music, and the participation of the state priesthood. According to some colonial accounts, the bodies of rulers were burned and their ashes scattered or buried in urns at key religious sites, such as the Templo Mayor.38 These funerals not only facilitated the deceased’s journey into the afterlife but also reaffirmed dynastic legitimacy and state theology through ritual performance and elite spectacle.

The living also maintained ongoing relationships with the dead through household shrines, annual festivals, and ritual offerings. Domestic altars often featured the remains of ancestors or symbolic relics, and households would periodically offer food, incense, and blood to maintain favor and protection. This practice paralleled the state-level commemorations of fallen warriors or rulers, whose memory was preserved through songs, dances, and calendrical rituals. The most significant of these was the festival Miccailhuitontli—later syncretized into the modern Día de los Muertos—during which families welcomed the dead back for a brief reunion. These acts of commemoration were not passive acts of grief but affirmations of cosmic and social order, integrating ancestors into the living world through ritual reciprocity.39 The dead, if properly honored, continued to serve as spiritual allies and protectors; if neglected, they could become restless, bringing misfortune or disease.

The spatial and material aspects of burial also reinforced Aztec cosmological models. Temples and homes were designed with sacred geography in mind, often aligning the body’s orientation with solar or cardinal directions. Caves and mountains—believed to be the birthplaces of humans and deities alike—were preferred locations for certain burials, especially among those with religious significance. The proximity of the dead to sacred features ensured the continuity of spiritual energy, reinforcing the notion that death was not a severance but a transference of being. In essence, Aztec burial customs were more than rituals for the dead—they were rituals for the living, designed to secure order, reciprocate divine sacrifice, and ensure that the rhythm of life, death, and rebirth remained uninterrupted within the great cosmic engine of the Fifth Sun.40

Human Sacrifice: Ritual Death as Cosmic Obligation

Among the Aztec, human sacrifice was not a barbaric excess but a foundational tenet of their metaphysical worldview—an act necessary to sustain the cosmos. The Aztecs believed that the gods had sacrificed themselves in primordial time to create the world, and that humans were born into a sacred debt (nextlācatl), bound to maintain cosmic balance by returning life essence—chalchiuatl, or “precious water,” their blood—to the divine. This reciprocity structured Aztec theology, legitimized warfare, and underpinned statecraft. Sacrifice was not merely religious spectacle; it was cosmic maintenance. Without offerings of blood and hearts, the sun would cease to rise, the rains would fail, and time itself would unravel.41 Thus, ritual death was not tragic—it was obligatory, a sacral act encoded in the very architecture of the Aztec state.

The central stage for this sacrificial drama was the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan, a twin-temple dedicated to Huitzilopochtli (god of the sun and war) and Tlaloc (god of rain and fertility). Here, victims—often captured warriors from xochiyaoyotl, or “flower wars”—were laid on a cuauhxicalli (sacrificial stone), where high priests used obsidian blades to cut open the chest and extract the still-beating heart. The heart was then burned or placed in a stone receptacle as an offering to the gods. This public rite was a ritual theater in which cosmic renewal was visibly enacted. Sacrifices were timed to coincide with calendrical festivals, solar events, and agricultural cycles, further tying ritual death to the temporal rhythm of the universe.42 The scale was staggering; during the dedication of the Templo Mayor in 1487 under Ahuitzotl, chroniclers claimed that thousands of victims were sacrificed over four days—a claim debated, but indicative of the rite’s symbolic magnitude.

Human sacrifice extended beyond war captives. Children were offered to Tlaloc in times of drought, their tears believed to summon rain. Slaves, selected for beauty or perfection, were sacrificed to Xipe Totec during Tlacaxipehualiztli, a spring festival marking renewal. These victims were paraded, honored, and treated as earthly embodiments of the gods they were meant to nourish. Particularly sacred were the ixiptla, impersonators of deities chosen to live for a year in ceremonial splendor before being sacrificed in the god’s name. This ritual transubstantiation transformed the victim from mere human into divine substance. Death, in this context, was not a punishment but an elevation—temporary deification followed by sacred dismemberment. The community did not mourn these deaths as losses but revered them as cosmically fruitful exchanges.43

Auto-sacrifice, or bloodletting by nobles and priests, complemented public sacrifice by reinforcing elite participation in the cosmic order. Using maguey spines or obsidian blades, individuals pierced ears, tongues, or genitals, offering their own blood to the gods. This private devotion mirrored the gods’ own self-sacrifice in myth and served to authenticate personal piety and priestly authority. Even rulers were expected to bleed as part of their ritual duties. Sacrificial ideology thus permeated every level of society, from the battlefield to the household altar. Rather than isolate death as a foreign intrusion into life, the Aztecs ritualized it as life’s sustaining force. Through the shedding of blood, life was not only preserved but ordered, divinely sanctioned, and renewed in cycles of sacred violence.44

European colonizers and missionaries viewed these practices with horror, using them as evidence of indigenous depravity and justification for conquest. Yet their revulsion obscured the profound theological coherence behind Aztec sacrifice. These rituals were grounded in an ethical system that valued balance, reciprocity, and continuity—not cruelty. To sacrifice was not to murder but to fulfill a cosmic role. Victims, particularly ixiptla, were revered, not reviled; they embodied divinity and secured collective survival. In the modern period, traces of these beliefs survive in Día de los Muertos and other commemorations that blur the line between the living and the dead. For the Aztecs, human sacrifice was never gratuitous—it was the price of existence, the ritual act by which the universe was fed and sustained.45

The Diachronic Continuity of Death Rituals

Despite the Spanish conquest and the violent imposition of Christianity in the sixteenth century, many elements of Aztec death ritual persisted—not in their original form, but through adaptation, concealment, and syncretic transformation. Spanish missionaries, appalled by human sacrifice and mortuary rites that did not conform to Christian doctrine, sought to eliminate what they saw as “pagan” practices. However, the underlying structure of Aztec ritual thinking—centered on reciprocity, ancestor veneration, and cyclical renewal—proved resilient. Indigenous peoples did not simply abandon their beliefs; they repurposed them within the new religious order. The Catholic calendar, saints’ cults, and even funerary practices were appropriated as vessels for older meanings. In particular, the cult of the dead, rather than being extinguished, evolved into forms legible to Christian authorities while maintaining core indigenous principles.46

One of the most striking examples of this ritual continuity is the celebration of Día de los Muertos, which, though shaped by Catholic observances like All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day, retains unmistakable pre-Columbian features. The offering of food, drink, flowers, and candles to the deceased mirrors ancient Aztec commemorations of the dead, particularly the Miccailhuitontli and Hueymiccailhuitl festivals. In these month-long rituals, families created household altars and brought offerings to cemeteries, believing that the souls of the departed returned temporarily to visit the living. Today’s altars, or ofrendas, frequently include pan de muerto, sugar skulls, marigolds, and images of saints or the Virgin Mary—but their function remains the same: to welcome the dead and reaffirm the permeability between the mortal and ancestral worlds.47 These traditions represent not rupture but resilience, a cultural palimpsest where Christian symbols overlay indigenous cosmology.

This persistence is also evident in the spatial practices of death. While colonial authorities insisted on Christian burials in consecrated cemeteries, many Nahua communities retained preferences for burial near the home or in places with sacred geographic significance, such as caves, trees, or mountain bases. These preferences reflected a deep-rooted Aztec cosmology in which the dead remained embedded in the landscape and continued to influence the living. Likewise, the practice of maintaining domestic shrines with relics, bones, or ritual items endured in many rural households despite ecclesiastical condemnation. These shrines functioned not only as memorials but as spiritual nodes—sites where offerings could be made, dreams interpreted, and guidance sought. The notion that the dead required ongoing care and could act as intercessors between humans and the divine remained fundamental.48 Even as the theological framing shifted from the tlalocan or mictlan to purgatory or heaven, the functional relationship between the living and dead endured.

The colonial period also saw the development of new syncretic figures who embodied indigenous ideas of death and the afterlife. One of the most potent symbols of this continuity is La Santa Muerte, the personified female figure of death venerated in many contemporary Mexican communities. Though not a direct continuation of Aztec deities like Mictlantecuhtli or Mictecacihuatl, Santa Muerte represents the reemergence of indigenous death ideologies within a modern context. Her iconography—often featuring a skeletal figure holding a scythe and globe, clad in robes and surrounded by candles—blends Catholic saint veneration with pre-Hispanic understandings of death as a force both feared and revered. Scholars have argued that Santa Muerte reflects a deeper cultural logic that predates Christianity: the belief in death as a sacred power, capable of both blessing and retribution.49 Such figures exemplify the capacity of Aztec ritual ideas to survive by transfiguring themselves within new symbolic frameworks.

Ultimately, the diachronic continuity of Aztec death rituals reveals not merely the endurance of tradition but the adaptability of a worldview grounded in ritual balance and sacred reciprocity. Through syncretism, reinterpretation, and cultural resistance, the logic of Aztec mortuary practices persisted long after the fall of the empire. Contemporary Mexican practices surrounding death—whether found in rural altars, national holidays, or the veneration of Santa Muerte—are not just cultural echoes; they are expressions of a living tradition. The Aztec dead were never wholly silent. They were carried forward in ritual, remembered in symbol, and reanimated in every marigold laid on an altar. In this way, the continuity of death ritual becomes a testament to cultural survival, in which the dead, far from being lost, remain agents in the preservation and transformation of indigenous identity.50

Conclusion: The Sacred Debt of Death

To understand Aztec death rituals is to confront a worldview radically different from modern Western sensibilities. In the Aztec cosmos, life and death were not opposites but interlocked realities, each feeding the other in a sacred economy of blood, sacrifice, and renewal. The dead were not lost; they were transformed, journeying through realms shaped by elemental forces and divine decrees. The living bore a spiritual debt—tequio—to nourish the gods with the only currency worthy of them: the essence of life itself.

In their temples, in their tombs, in the vast choreographies of their ritual calendar, the Aztecs encoded a civilization founded on death—and yet, paradoxically, obsessed with ensuring life. Their rituals were not morbid spectacles, but urgent metaphysical acts to keep the sun alight, the maize growing, and time itself in motion.

In the obsidian mirror of their rituals, we see a reflection not of savagery, but of sacred seriousness—a people who, understanding the fragility of existence, dared to meet death not with denial, but with offering.

The Sacred Passage: Incan Death Rituals and the Journey Beyond

Overview

The Inca Empire, known as Tawantinsuyu, was one of the largest and most sophisticated civilizations in pre-Columbian America, flourishing in the Andes before the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. At its height, it encompassed a vast territory stretching from present-day Colombia to Chile. Despite lacking a written language, the Inca developed intricate social, political, and religious systems, including complex funerary and death rituals that reflected their worldview. Death, for the Inca, was not an end but a transition—a passage to another plane of existence. Their beliefs and practices surrounding death provide deep insight into their cosmology, political structure, and relationship with the natural and supernatural worlds.

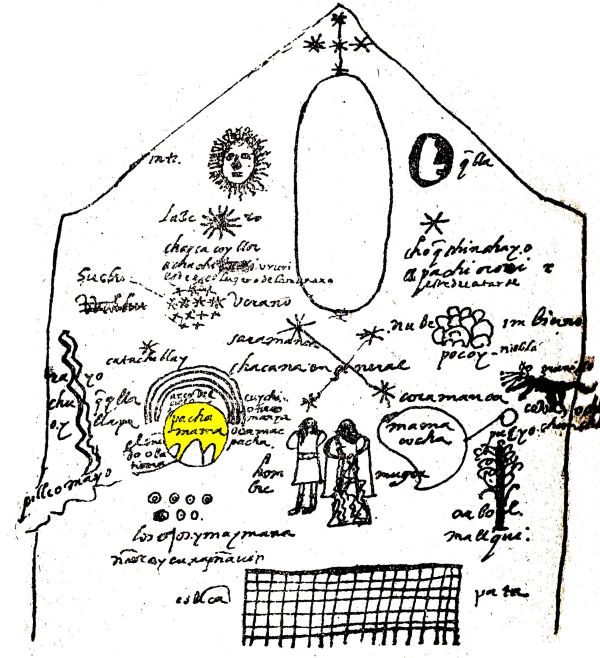

Cosmology and the Incan Concept of the Soul

In Incan cosmology, the universe was structured as a tripartite reality, composed of Hanan Pacha (the upper world), Kay Pacha (the earthly world), and Uku Pacha (the inner or lower world). These realms were not isolated but interconnected through a spiritual energy known as camaquen, a life force that animated all beings—gods, humans, animals, and even stones and mountains. The Inca viewed existence as a cyclical flow of energy across these realms, and the soul, or aya, was both part of this current and a distinct entity. Unlike the Western concept of the immortal soul as an essence separate from the body, the aya was bound to place, ancestry, and the natural order. Upon death, the soul did not ascend or descend in a moral judgmental framework, but transitioned into a different ontological state, remaining connected to both family and landscape.51 The dead were not absent but continued to participate in the cosmic harmony through ritual and memory.

The aya occupied a liminal position between the living and the divine. Its journey after death depended heavily on how the individual had lived, the cause of death, and their social role. Righteous individuals were believed to ascend to Hanan Pacha, a luminous realm associated with the sun god Inti and celestial order. Others might enter Uku Pacha, not as punishment but as a necessary passage—a fertile, mysterious world of ancestors and subterranean forces. Importantly, the soul did not vanish from Kay Pacha entirely. Through mummification and ancestor veneration, the Inca preserved the aya of elite individuals—especially rulers—allowing their presence to remain active in civic, ceremonial, and even political affairs.52 This fluidity between the realms demonstrates the Inca’s non-linear, spatially grounded vision of spiritual existence.

The Inca understood the soul not as a fixed, singular entity but as a composite with multiple expressions. According to some scholars, Incan thought distinguished between the aya (the shadow or spirit), the sami (the vital essence), and the kancha (a kind of aura or power field). These components of personhood could persist in different ways after death—some residing in sacred landscapes or ancestral mummies, others absorbed into the collective energy of the community or the divine. The process of death, therefore, was not simply a departure but a redistribution of being.53 It was through ritual that this redistribution was managed: offerings, prayers, libations of chicha (corn beer), and songs ensured that the aya continued its journey in balance with the cosmic order. Ritual neglect, by contrast, could result in spiritual disorder, causing the dead to become restless or even dangerous.

Ancestral mummies (mallki) played a crucial role in sustaining this cosmic relationship. Far from being passive corpses, these preserved bodies were treated as living extensions of their former selves. Mummies were clothed, fed, consulted, and included in festivals. Royal mummies, in particular, were paraded in public, housed in estates, and given lands that produced tribute for their continued maintenance. These practices reinforced the belief that the aya retained agency and presence. The souls of the dead, particularly the noble dead, were not relegated to an invisible realm but made tangible through ritual, land, and political memory.54 This ritual materialism emphasized that the soul’s enduring vitality depended not only on metaphysical belief but on active social practices that kept the dead within the living community.

Ultimately, the Incan concept of the soul cannot be understood apart from its cosmology of reciprocity, place, and energy. The aya was not a disembodied ghost nor a morally judged spirit, but a dynamic force embedded in the cycles of nature, community, and ancestry. In death, the soul entered into new relationships, affecting the living through weather, fertility, and fortune. The maintenance of these relationships was a sacred duty, one that blended theology, politics, and ecology into a unified spiritual system. The Incan soul was thus an agent of continuity—neither severed by death nor exalted into abstraction, but folded back into the rhythms of a world where every mountain had a spirit, every ancestor had a voice, and every death was a return.55

Death and the Role of Ancestors

In Inca society, death did not mark the cessation of agency or identity; rather, it marked the beginning of a new and vital role as ancestor. The deceased, particularly those of noble or royal status, remained key actors in social, political, and religious life. Ancestor veneration formed the bedrock of Andean religious practice long before the rise of the Inca, but the empire institutionalized and expanded it into a state-sanctioned cult that integrated kinship, land ownership, and divine authority. The dead were not merely remembered—they were ritually engaged, housed, fed, and consulted. The ancestral spirit, or aya, was believed to remain near the body and to continue influencing the world of the living. Through this belief, the Inca developed a ritual economy centered on maintaining relationships with the departed, ensuring that the dead continued to nourish the living through fertility, guidance, and protection.56

This system of ancestor veneration was most visibly embodied in the cult of the royal mummies, or mallki. After an emperor’s death, his body was mummified and preserved in lifelike form, dressed in fine garments and adorned with regalia. These mummies were not hidden away in crypts but installed in palaces or ceremonial compounds, where they received food offerings, chicha (corn beer), and tribute from their lands. Each mallki retained estates and servants, managed by descendants and ritual specialists. In this way, deceased rulers remained legal and spiritual authorities, wielding power and receiving wealth even after death. Spanish chroniclers like Pedro Cieza de León and Bernabé Cobo were both astonished and disturbed by these practices, describing how the Inca would carry their mummified ancestors to festivals, speak to them, and “consult” them on matters of state.57 This ritual presence was not metaphorical—it was institutional, with entire kin groups, or ayllus, organized around the caretaking and political authority of the deceased.

The political function of ancestors extended beyond the royal family. Non-elite Inca communities also practiced forms of ancestor veneration, though typically on a smaller and more localized scale. Commoner families might bury their dead beneath the floors of their homes, maintaining a spatial and spiritual intimacy with the deceased. Periodic offerings of food, coca leaves, and chicha were made to household ancestors, often accompanied by whispered prayers or ritual chants. Mountains, caves, and other natural features often served as the dwelling places of ancestral spirits and were treated with reverence. These practices illustrate a continuity in Andean spiritual logic: that ancestors, far from being gone, were present in the landscape and actively involved in communal life.58 Such beliefs blurred the boundary between past and present, allowing the dead to remain active within the social fabric through ritual maintenance.

The mummified ancestors also played critical roles during seasonal and calendrical ceremonies. During major festivals such as Inti Raymi (the festival of the sun), royal mallki were brought out of their compounds, paraded in public processions, and seated alongside living dignitaries. These ceremonial appearances reaffirmed not only continuity with the past but also divine sanction for present rulers, who derived legitimacy from their connection to the sacred dead. Some scholars have noted that the Inca conception of rulership was dynastic in form but ancestral in function; the living Sapa Inca was not an individual above others, but a continuation of an immortal lineage sustained by ritual and memory.59 The dead thus operated as guardians of political order, cosmic balance, and ancestral legitimacy—serving not only as spiritual beings but as ideational and institutional pillars of the state.

Spanish attempts to eradicate ancestor veneration met with limited success. Colonial authorities deemed the practice idolatrous and sought to destroy mummies and sacred bundles (quipu or huaca), fearing the political and spiritual power they embodied. Many mallki were hidden by surviving ayllu members, and their ritual functions were transformed into Christian-compatible forms, such as saint veneration or cemetery rituals. Nonetheless, the core logic of ancestor veneration persisted. In rural Andean communities today, the dead are still honored with offerings, household shrines, and cemetery vigils that echo Incan ritual structures. The ancestors remain intermediaries between the living and the divine, continuing to protect crops, grant fertility, and uphold social cohesion. Death, in the Inca world and its cultural descendants, was never an erasure—it was a redistribution of power into new realms of influence, anchored in ritual remembrance and the sacred geography of kinship.60

Funerary Practices and Burial Customs

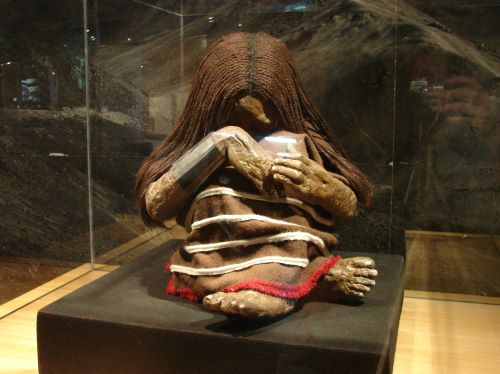

Funerary practices among the Inca were deeply rooted in their cosmological understanding of life, death, and rebirth. Death was viewed not as an end but as a transition into another form of existence within a spiritually charged cosmos. Accordingly, burial customs reflected a desire to facilitate the soul’s journey through the three realms of Inca cosmology: Hanan Pacha (the upper world), Kay Pacha (the earthly plane), and Uku Pacha (the inner world). The dead were often buried in a fetal position, symbolizing return to the womb of Pachamama—Mother Earth—and suggesting the cyclical nature of life and death. This positioning, combined with the inclusion of grave goods and ritual offerings, highlights the Inca belief that proper burial was essential not only for the wellbeing of the deceased’s aya (spirit), but also for maintaining social and cosmic balance.61 The treatment of the body was a sacred act of reintegration into the animate earth.

Burials varied widely depending on the individual’s social status, geographic location, and cause of death. Among the common people, interment often occurred within or near the home or in community cemeteries, frequently marked by cairns or simple stone structures. These graves usually contained offerings such as pottery, food, textiles, coca leaves, and tools—items the deceased would need in the afterlife. The wealth and variety of these grave goods were typically modest, though they still reflected the broader Andean emphasis on ritual reciprocity. In more affluent or noble households, burials might involve specially constructed tombs or crypts, often within caves, rock outcroppings, or carved niches in the mountainside—places considered sacred access points to Uku Pacha. These locations were not chosen randomly; they reflected a sacral geography in which certain natural features were believed to serve as portals between the worlds.62

Among the elite, funerary practices became highly elaborate, incorporating mummification, ritual feasting, and long-term care of the deceased. The bodies of nobles—particularly former rulers—were embalmed using desiccation methods involving exposure to dry air, smoke, or burial in cool, arid caves. These mummies, or mallki, were seated, clothed, and provided with masks or coverings to preserve their identity. The funerary ceremony itself could last several days, including processions, dances, libations of chicha, and communal feasts that linked the living with the dead through reciprocal exchange. Inca society understood the moment of death not only as a personal transition but as a communal and cosmic event requiring public acknowledgment and ritual attention.63 The funeral was thus a liminal rite, ensuring the deceased’s successful journey while reinforcing social cohesion and ancestral continuity among the living.

Particularly noteworthy was the architectural investment in chullpas—above-ground funerary towers found throughout the Andes, particularly in the highlands of modern Peru and Bolivia. These circular or square structures housed mummified ancestors, often of noble or local lineage. Though their exact origin predated the Inca, the imperial state adopted and adapted them, incorporating chullpas into their broader system of ancestral veneration and land tenure. These tombs were sometimes located along ceque lines in Cuzco’s sacred geography, further embedding the dead into ritual and political networks. Their construction reflected not only a concern for the dignity of the deceased but a desire to render the ancestors visibly and ritually accessible to the community.64 Chullpas functioned as sites of remembrance, oracles of authority, and material anchors of lineage identity. Through these built forms, the Inca made permanent the reciprocal obligations between generations.

Funerary practices among the Inca were thus not merely acts of disposal or remembrance—they were spiritual technologies designed to preserve balance within the cosmos and community. The ritualized treatment of the dead ensured that the aya did not become restless or malevolent and that the living continued to enjoy fertility, prosperity, and ancestral guidance. In the post-conquest period, many of these practices were suppressed or reinterpreted through Catholic doctrine, yet their structural logics remained. Contemporary Andean communities continue to perform burial rites that echo Inca traditions: household offerings to the dead, burial with goods, and reverence for sacred landscapes remain integral to the cultural life of the region. In this way, Incan funerary customs persist—not only in memory but in practice—sustaining a cosmology in which the dead are never absent, only transformed.65

Rituals of Mourning and Commemoration

Mourning among the Inca was not merely a private or familial response to death but a deeply codified set of rituals that reflected cosmological beliefs and reinforced social cohesion. Mourning rituals varied depending on the social status of the deceased, but all shared the goal of facilitating the proper transition of the soul (aya) and restoring equilibrium within the community. Upon death, the body was washed, adorned, and often placed in a seated, fetal position, while the family and community engaged in lamentation, fasting, and ritual wailing. The mourning period, known as llaki, was marked by prescribed behaviors, including abstention from certain foods, cessation of music and dancing, and sometimes the smearing of ash or dirt on the face as a sign of grief.66 These practices reinforced the significance of the deceased’s passage from the Kay Pacha to either the Hanan Pacha or Uku Pacha, while reaffirming collective bonds among the living.

The duration and intensity of mourning were proportionate to the social rank of the deceased. For commoners, mourning may have lasted a few days to a week, while for nobles and royals, it could extend for months and involved elaborate public ceremonies. Among the elite, ritual specialists orchestrated formalized rites that included feasting, sacrifices (often of llamas or guinea pigs), music, and offerings to the gods and the deceased. Chroniclers such as Garcilaso de la Vega describe prolonged mourning periods for Inca emperors, during which their subjects would abstain from work, wear black garments, and participate in mass rituals to honor the mallki (mummy) of the departed ruler.67 These events functioned not only as expressions of grief but as performative affirmations of dynastic continuity and the enduring presence of the dead within the political and cosmic order.

Central to the commemoration of the dead were periodic rituals that honored ancestors through offerings and ceremonial feasts. These rites were often tied to the agricultural calendar and solstice festivals, particularly Inti Raymi, during which royal mummies were paraded and venerated alongside living nobility. In these contexts, the dead were not remembered from a distance—they were present. Their mallki were dressed, fed, and given voice through ritual dialogue. This sustained interaction between the living and the dead emphasized the Andean view that death did not sever social or spiritual ties, but transformed them into a new mode of relationship requiring ongoing care and acknowledgment.68 The community’s health, fertility, and prosperity were believed to depend in part on this continued reverence, as the ancestors were capable of intervening in the affairs of the living.

Inca commemorative practices also extended to ritual sites and architecture. The placement of chullpas (funerary towers), huacas (sacred objects or places), and ceremonial plazas often reflected alignment with solar, lunar, or stellar phenomena, reinforcing the relationship between death and cosmic rhythms. These spaces became focal points for annual remembrance ceremonies, during which offerings were left at tombs, songs and dances were performed, and oracles consulted. In rural areas, family members continued to visit graves regularly, bringing chicha, coca leaves, and food as gestures of devotion. Even after the Spanish conquest, these customs endured under different guises, with Catholic saints replacing mallki, and cemetery visits on All Souls’ Day maintaining the structure of earlier commemorations.69 Despite ecclesiastical opposition, the logic of ritual remembrance persisted, proving more resilient than the institutions that sought to suppress it.

Ultimately, rituals of mourning and commemoration among the Inca served multiple purposes—emotional, religious, political, and cosmological. They allowed individuals and communities to process grief while maintaining social order; they reaffirmed the continuity of kinship and state through public display; and they enacted the theological belief that the dead remained vital participants in earthly affairs. The Inca worldview did not isolate death from life but integrated it into a cyclical, sacred continuum. Mourning and commemorative rites thus constituted not the aftermath of death but its liturgical fulfillment: a set of obligations owed to the dead, whose continued favor ensured the flourishing of the living.70 These practices continue to echo in modern Andean communities, where ancestor reverence, ritual lamentation, and calendrical remembrance remain woven into the cultural fabric.

Sacrifice and Human Offerings

Sacrifice, including human offering, was a core element of Incan state religion, rooted in the Andean cosmology of reciprocity known as ayni—the principle of mutual exchange between humans, nature, and the divine. The Inca believed the gods had given life, fertility, and order to the world, and thus required nourishment in return. This nourishment often took the form of food, chicha, coca leaves, textiles, and animals such as llamas, but on especially significant occasions, human lives were offered. These rituals were not undertaken lightly or regularly; human sacrifice was generally reserved for exceptional events: coronations, famines, solar eclipses, military victories, or natural disasters. These moments were seen as thresholds in the temporal and cosmic order, and human sacrifice functioned as a mechanism to restore balance between the Kay Pacha (the world of the living) and Hanan Pacha (the upper world).71

The most famous and well-documented form of Inca human sacrifice was the capacocha ceremony, in which children were ritually offered to the gods. According to colonial chroniclers such as Cristóbal de Molina and Juan de Betanzos, these children were selected for their physical perfection and noble lineage, often coming from high-status families across the empire. They were brought to Cuzco, honored in grand ceremonies, and then led to remote mountaintops—apus—considered sacred dwellings of the gods. There, they were ritually killed through suffocation, blunt force trauma, or being buried alive, depending on the local tradition. Archaeological evidence, such as the extraordinary frozen mummies discovered on Mount Llullaillaco, Ampato, and Misti, confirms the accounts: the bodies were immaculately preserved, dressed in fine garments, and surrounded by miniature offerings of gold, silver, ceramics, and textiles.72 These children were not seen as victims but as divine messengers—bridges between humanity and the gods.

The sacrificial process was surrounded by intensive ritual preparation. Before their death, the chosen children were honored guests, given ceremonial feasts and ritual purification. Their journeys to their sacrificial sites were processions of religious gravity, reenacting mythological routes and sanctifying imperial geography. The performance of these rites served both theological and political purposes: they appeased deities such as Inti (the sun), Pachamama (earth), and Illapa (thunder), while also reinforcing the Inca emperor’s role as the divine mediator between the natural and supernatural realms. The empire’s ability to mobilize people and goods for such elaborate ceremonies also served to reaffirm imperial reach, absorbing local elites into a shared ritual framework that validated Cuzco’s supremacy.73 In this way, sacrifice was not only a religious act but a performance of state ideology—a unifying spectacle of cosmic and political order.

Animal sacrifice, especially of llamas and alpacas, was far more common and served many of the same ritual functions on a local scale. These animals were offered during agricultural festivals, solstices, and times of hardship to ensure good harvests, rainfall, or protection from illness. The ritual killing often involved slitting the throat or removing the heart, and the blood would be used to anoint sacred objects or poured over fields. In some cases, the liver was examined for omens—a form of divination that guided future action. Though less dramatic than human sacrifice, these rites also drew upon the logic of reciprocity and renewal. The offering of a life, human or animal, was considered a powerful act that secured divine favor and maintained equilibrium between the sacred and the mundane.74 Every death within this framework was a continuation of life in the broader cosmic order.

Colonial narratives framed Incan human sacrifice as barbaric, but such accounts were often colored by the agendas of Spanish clerics eager to justify conquest and conversion. Yet modern archaeology and ethnography have confirmed both the existence and complexity of these practices. Far from indiscriminate cruelty, Incan sacrifice was structured, solemn, and ideologically rich. It represented the Inca’s commitment to sustaining a fragile world through ritual exchange. In the sacrifices made atop mountains and in high temples, the Inca expressed a deep spiritual and political philosophy—one in which life, death, and empire were all bound within a sacred cycle of giving and receiving. The dead were not lost; they were transformed into agents of fertility, protection, and cosmic balance.75

The Disruption of Incan Death Rituals by Spanish Conquest

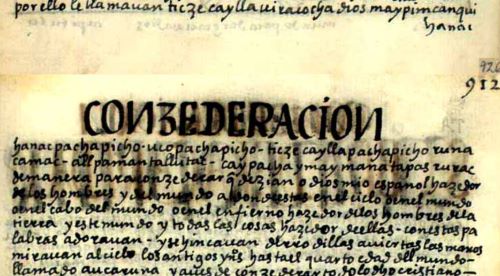

The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire in the early 16th century brought catastrophic upheaval not only to the political and economic structures of Andean society but also to the deeply rooted spiritual systems that governed life, death, and the afterlife. Central among these disruptions was the targeted dismantling of Incan mortuary rituals and ancestor veneration practices, which the Spanish viewed as pagan, idolatrous, and dangerously subversive. The veneration of mallki—mummified ancestors, particularly of past emperors—was seen as a direct threat to colonial authority, not merely because it reflected non-Christian spiritual beliefs, but because it preserved pre-Hispanic political legitimacy. The Spanish understood that these ancestral remains were not inert symbols of the past; they were actively revered as living presences with ritual power. To sever the link between the dead and the living was, therefore, not only a religious imperative for missionaries but a calculated act of imperial control.76

Spanish friars and colonial authorities sought to destroy the sacred infrastructure that sustained Incan death rituals. Mummies were exhumed from their shrines and paraded through public squares to humiliate indigenous beliefs before being burned or entombed in Christian cemeteries. Temples and chullpas were razed or repurposed as churches, and rituals involving offerings to the dead were outlawed under threat of punishment. In many cases, local communities resisted these efforts covertly, hiding mallki or transferring their veneration to Christian saints and relics in a process of syncretic adaptation. Nonetheless, the loss of the physical presence of mummified ancestors marked a fundamental rupture in Inca religious life. Without the embodied aya—the spiritually potent ancestor—the carefully maintained cycles of reciprocity between the living and the dead were disrupted, and the continuity of cosmic balance was thrown into question.77