How we care for our dead, and what such care reveals about how we live.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Death, the great equalizer, has long held a mirror to the values, beliefs, and anxieties of American society. The manner in which a culture treats its dead offers a revealing window into its social fabric, economic priorities, and spiritual frameworks. In the United States, death care—the systems, customs, and industries associated with handling the dead—has undergone profound transformation. From early colonial burial rites shaped by European tradition, to the rise of the professional funeral industry, to today’s evolving green and alternative death movements, the trajectory of American death care is a reflection of broader historical currents: industrialization, urbanization, medicalization, and cultural individualism.

Colonial and Early American Death Practices: Communal and Religious

In early Colonial America, death was a deeply communal and religious affair, reflecting both the European cultural roots of settlers and the harsh realities of colonial life. Puritan New England, in particular, developed a sober and theologically weighty approach to death. The Puritan worldview viewed life as a moral trial and death as a moment of judgment and spiritual consequence. Funerals were not celebrations of life, but rather didactic events emphasizing human mortality and the necessity of salvation. The dead were often buried quickly due to the absence of preservation techniques, and services included sermons warning the living of divine judgment. This somberness stood in contrast to the more ritualistic death traditions of Anglicans or Catholics, though even in those cases, religious meaning was central. Regardless of denomination, death was seen as both inevitable and spiritually significant—a rupture that required collective reflection and religious ritual.1

Death care in this period remained largely within the domain of the family and local community. The preparation of the body, construction of coffins, and digging of graves were typically handled by kin or neighbors. There were no professional undertakers or funeral homes. The body was washed, dressed in a simple shroud, and placed in a handmade wooden coffin, often constructed by local carpenters. Families would then host wakes at home, and the dead were transported to churchyards or family plots for burial. Gravestones were modest, if present at all, and those who could afford them frequently employed local artisans to carve them with memento mori imagery such as skulls, hourglasses, and winged death’s heads.2 These symbols reinforced Puritan beliefs in the fleeting nature of life and the omnipresence of death, while subtly encouraging repentance and piety among the living.

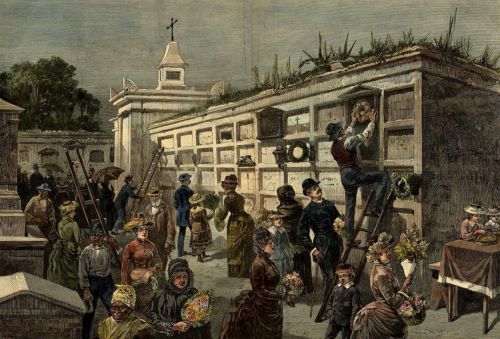

Throughout the colonies, burial grounds were typically located near churches, reflecting the close relationship between ecclesiastical authority and death rites. In New England, town burial grounds became civic as well as sacred spaces, often positioned centrally in a community to reinforce death’s public dimension.3 Such graveyards were frequently unlandscaped and utilitarian, further reflecting Protestant rejection of the ornate Catholic burial traditions of Europe. In the Southern colonies, however, where Anglican influence was stronger, gentry families often buried their dead on private plantations, reinforcing kinship ties and social status. African and Indigenous practices, meanwhile, persisted in private or syncretized forms among enslaved people and Native communities, often blending Christian symbolism with ancestral rites, although such traditions were frequently marginalized or repressed by colonial authorities.4

The colonial approach to mourning was likewise highly structured, particularly among the more affluent. In Puritan New England, overt displays of grief were discouraged as potentially vain or spiritually inappropriate, but mourning customs nonetheless developed over time. By the late seventeenth century, it became common for wealthier families to distribute mourning gloves, rings, or cloth to funeral attendees. These items served both as tokens of grief and social status, indicating that while death was spiritually humbling, it could also reflect one’s place in the earthly hierarchy.5 Later in the 18th century, mourning became more sentimental, with gravestone imagery shifting toward urns and willows, signaling a gradual movement from stark religious fatalism to a softer, more emotional relationship with loss. This transformation paralleled broader cultural changes associated with the Enlightenment and the rise of Romanticism.

Despite the theological differences and regional variations, early American death care was profoundly shaped by a communal ethic. There was little separation between the personal and the social, the domestic and the sacred. Death was not a private, professionalized event as it would later become in the 19th and 20th centuries. Instead, it was a moment for collective religious observance, social solidarity, and moral instruction. The care of the dead was considered a sacred obligation, and burial rites reinforced communal bonds.6 Even as Enlightenment ideals and emerging capitalist economies would gradually individualize and commercialize death in the centuries to come, the colonial period remains a powerful example of how deeply embedded death was within the moral and spiritual rhythms of everyday life in early America.

The Nineteenth Century: Professionalization and the Rise of the Funeral Industry

The nineteenth century witnessed the transformation of American death care from a religious and family-centered activity into a professionalized and increasingly commercial enterprise. Central to this shift was the rise of the undertaker, a figure who initially emerged as a facilitator of burial logistics but gradually expanded their role into that of a full-service death care provider. In the early decades of the century, local carpenters and cabinetmakers commonly provided coffins as part of their trade, and communities still handled most aspects of death preparation.7 However, as urban populations grew and technological developments made body preservation more feasible, a distinct profession began to coalesce around the needs of the dead and their families. The growing presence of undertakers reflected not only changes in demography and economics but also an evolving cultural discomfort with direct contact with the dead, paving the way for a specialized class of death professionals.

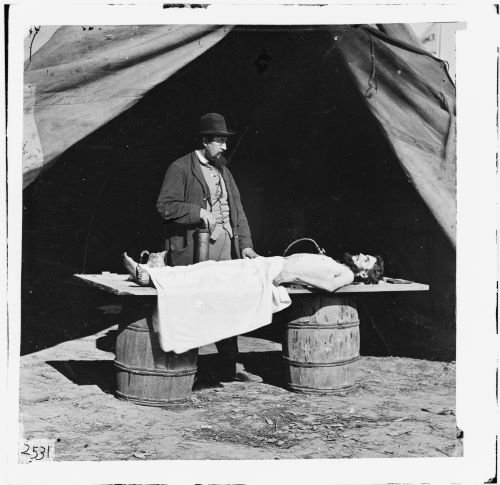

A critical turning point in this transformation was the American Civil War (1861–1865), which created both logistical necessity and public exposure to new embalming techniques. The desire of families to have the bodies of fallen soldiers returned home led to the widespread adoption of embalming, a practice that had existed in rudimentary forms but was rarely used outside of medical schools or anatomical studies. Embalmers such as Dr. Thomas Holmes—considered the “father of modern embalming”—rose to prominence during this time, preserving bodies for long-distance transport and public viewing.8 The practice received national attention during the post-assassination funeral of President Abraham Lincoln in 1865. His body was embalmed and displayed on a widely publicized train journey, allowing mourners across the country to pay their respects. The public acceptance of embalming following Lincoln’s funeral helped legitimize the procedure and expand its popularity in peacetime.9

The success of embalming after the war created an opening for undertakers to claim professional authority over the dead. No longer mere coffin-sellers or gravediggers, they began offering embalming services, managing funeral arrangements, and establishing funeral parlors to replace home visitations. These mortuary businesses symbolized a larger trend in nineteenth-century American life: the movement of life’s major events—birth, illness, and death—from the home to institutional settings.10 As more families opted to outsource death care to professionals, undertakers responded by organizing themselves into trade associations, advocating for licensing requirements, and developing formal training programs. In 1882, the National Funeral Directors Association (NFDA) was founded, marking a key moment in the consolidation of funeral directing as a recognized vocation.11 By the turn of the century, embalming had become the dominant mode of corpse preparation, and funeral directors positioned themselves as experts in both sanitary science and emotional support.

These changes did not occur in a vacuum. They were part of a broader set of cultural and scientific currents, including the rise of the public health movement, the increasing authority of medical science, and the growing middle-class emphasis on propriety and decorum. Victorian mourning culture, with its elaborate rituals, dress codes, and material tokens, aligned well with the emerging funeral industry’s services. Funeral homes capitalized on these cultural expectations by offering ornate caskets, decorative mourning attire, and professionally orchestrated ceremonies.12 At the same time, the fear of miasma—the belief that decaying bodies emitted disease-causing vapors—helped promote embalming and burial in sealed vaults.13 Death was no longer seen as a natural and familial event, but rather as a potentially dangerous and emotionally disruptive occurrence best managed by trained specialists.

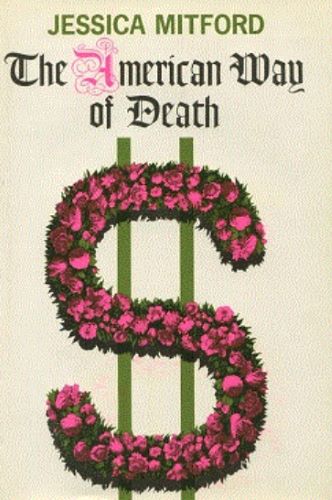

By the end of the nineteenth century, the American funeral industry had become both institutionalized and increasingly profitable. The shift from communal responsibility to professional service represented a profound change in how Americans engaged with mortality. Death care was no longer the domain of kin and congregation alone, but of business and bureaucracy. While this development allowed for standardized practices and arguably more dignified conditions, it also distanced the living from the dead and reframed mourning as a consumer experience.14 The stage was thus set for the twentieth-century critique of the “American way of death”—a phrase that would later crystallize the tensions between reverence and commodification, grief and profit, in modern funeral practices.

The Twentieth Century: Corporatization and Cultural Shift

By the dawn of the twentieth century, the American funeral industry had achieved full institutionalization, positioning itself as a necessary—and often unquestioned—element of modern life. Embalming had become the dominant method of body preservation, and the services of funeral directors were nearly universal for middle-class Americans. What began in the previous century as a process of professionalization now accelerated into corporatization, as small, family-run funeral homes began consolidating into larger businesses.15 This shift coincided with other American trends: urbanization, consumerism, and an increasing reliance on specialists to manage life’s most personal events. The once-intimate rituals surrounding death had become thoroughly commodified. Funeral homes were no longer simply service providers; they were branded, commercial enterprises offering standardized packages and options, complete with price sheets, financing, and upselling practices.

Central to the expansion of the funeral industry was the development of funeral chains and national networks, most notably Service Corporation International (SCI), which was founded in 1962 in Houston, Texas. By acquiring independent funeral homes and retaining their names to preserve the appearance of local identity, SCI and other conglomerates built vast networks under the surface of apparent continuity.16 This created an illusion of tradition and personal touch while shifting control of death care into the hands of centralized corporate entities. By the 1980s and 1990s, SCI had acquired thousands of funeral homes and cemeteries across the United States and abroad, effectively creating a multinational death care conglomerate.17 Corporatization enabled economies of scale and uniformity, but it also distanced the death care process further from its cultural and emotional roots, recasting grief as a transactional event.

Simultaneously, the cultural understanding of death underwent a transformation, shaped in part by broader social and technological changes. The early 20th century saw the emergence of hospitals and nursing homes as the dominant sites of death, replacing the home as the customary place of passing. As dying became medicalized and often hidden from public view, the rituals associated with it became more formulaic and institutional.18 Funeral directors assumed a quasi-clinical role, managing the appearance of the deceased through embalming, cosmetics, and restorative art. They were not only caretakers of the dead but curators of memory, shaping how mourners experienced loss. This new model emphasized presentation and decorum—the peaceful visage in the casket, the orderly procession, the polished language of condolence—over direct confrontation with mortality. Death became “clean,” hidden behind layers of aesthetic and professional mediation.19

Yet this sanitization and commodification of death did not go without criticism. In 1963, journalist and activist Jessica Mitford published The American Way of Death, a scathing exposé of the funeral industry that ignited public scrutiny.20 Mitford accused funeral directors of exploiting grief for profit, inflating prices for unnecessary services, and preying on vulnerable families. Her work helped catalyze the Federal Trade Commission’s Funeral Rule of 1984, which required funeral homes to provide transparent pricing and prohibited deceptive practices such as bundling required and optional services.21 Despite regulatory reforms, however, many of Mitford’s criticisms remain relevant in the modern funeral economy. The American way of death, she argued, had become a uniquely consumerist phenomenon, shaped more by business models than spiritual or communal needs.

As the century progressed, cultural attitudes toward death began to shift once again. The latter decades of the twentieth century saw the early seeds of alternative and personalized death care, foreshadowing the movements that would blossom in the twenty-first. More Americans began seeking cremation, which was legalized throughout the United States by the 1960s and grew steadily thereafter, partly due to lower costs and a loosening of religious taboos.22 Simultaneously, the counterculture and environmental movements began challenging the environmental costs and emotional sterility of modern funerals. Home funerals, natural burials, and spiritual diversity gained traction, suggesting a growing unease with the industrial model of death.23 Although the corporatized funeral industry remained dominant at century’s end, cracks had begun to form in its polished façade, as Americans slowly reclaimed death as a personal and, increasingly, ecological event.

The Turn of the Millennium: Decline of Tradition and Rise of Alternatives

As the United States entered the twenty-first century, the long-dominant model of traditional funerals—embalming, viewing, religious service, and casketed burial—began to show significant signs of erosion. Americans increasingly sought alternatives to the formulaic rituals and high costs associated with the corporate funeral industry. A central element of this shift was the surging popularity of cremation, which by 2016 surpassed burial as the most common method of body disposition in the United States.24 Economic motivations were a major factor; cremation is often a fraction of the cost of a traditional burial. But cultural and spiritual changes also played a role: the decline of organized religion, the rise of individualism, and a growing embrace of personalization in end-of-life decisions all made cremation more attractive.25 No longer stigmatized as irreverent or impious, cremation came to be seen as pragmatic, flexible, and emotionally adaptable—a blank slate for memorialization rather than a rigid rite.

Alongside cremation, the early 2000s saw a marked revival of home-based and family-centered death care. Home funerals, which had all but vanished during the twentieth century, experienced a grassroots resurgence fueled by critiques of institutional death care and a desire to reclaim death as a personal, communal, and even sacred event. Advocates emphasized the right of families to care for their dead without interference from corporate funeral homes. Groups like the National Home Funeral Alliance, founded in 2005, provided resources and legal guidance to those wishing to wash, dress, and vigil with the deceased at home.26 This movement mirrored similar trends in birth care, where midwifery and home births were resurging in response to the medicalization of childbirth. In both cases, the turn toward domestic rituals was a statement against professional detachment and in favor of intimacy, authenticity, and control.

Another defining development at the turn of the millennium was the emergence of green burial and ecological death practices. These approaches aimed to minimize environmental impact by forgoing embalming, metal caskets, and concrete burial vaults in favor of biodegradable materials and natural settings. Green burial grounds—often designed as conservation spaces—offered an alternative to the manicured lawns and rigid rows of conventional cemeteries.27 Advocates framed their work in both ecological and philosophical terms: returning the body to the earth, reducing carbon footprints, and embracing death as part of life’s ecological cycle. State laws and cemetery regulations, however, posed early obstacles. Nevertheless, the movement gained ground, especially after the 2007 founding of the Green Burial Council, which established certification standards for providers and burial sites.28 This shift toward “earth-conscious death” reflected broader cultural concerns about sustainability and a desire for continuity with nature even in death.

The new millennium also gave rise to a broader cultural movement known as death positivity, which encouraged open conversations about mortality, challenged taboos, and promoted informed end-of-life choices. Spearheaded by public figures like Caitlin Doughty, a mortician and author of Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, the movement built on the feminist and DIY ethics of the 1990s while responding to the commodification of grief.29 Doughty and others used blogs, podcasts, and social media to educate the public on everything from cremation options to the legality of home funerals and human composting. The phrase “death positive” emerged as a counter to the American tendency to medicalize, outsource, and emotionally repress death. Workshops, “death cafés,” and community memorial events provided spaces where people could discuss mortality in non-institutional settings. Far from morbid, the movement sought to restore death to public life—emotionally, intellectually, and ritually—while offering alternatives to what many saw as an overly sanitized and transactional death culture.

The cumulative result of these trends has been the fragmentation and personalization of death care in the United States. Rather than a single American way of death, the early twenty-first century has produced a diverse menu of practices: cremation and burial, religious and secular, corporate and home-based, conventional and green, all coexisting in a loosely regulated landscape. Technology has further expanded these options, enabling digital memorials, livestreamed funerals, and online grief communities.30 Yet access to these choices remains uneven. Socioeconomic inequality, geographic variation in laws, and cultural stigma continue to limit the reach of alternative death care. Even so, the turn of the millennium marks a crucial pivot in the history of American death culture—a moment when tradition gave way to innovation, and the care of the dead began once again to reflect the changing spiritual, ecological, and emotional values of the living.

The Contemporary Landscape: Fragmentation and Choice

The contemporary American death care landscape is characterized by a remarkable degree of fragmentation, consumer choice, and cultural pluralism. No longer dominated by a single prevailing model of funeral practice, death care in the United States now encompasses a broad range of options reflecting religious diversity, socioeconomic stratification, environmental values, and evolving ideas about identity and legacy. Consumers can choose between traditional embalming and casketed burial, cremation with customizable urns, alkaline hydrolysis (aquamation), or human composting, all depending on state legality and personal conviction.31 The funeral, once a standardized rite anchored by religious ritual and professional decorum, has become an open canvas for personalization. Services may now take the form of life celebrations, secular gatherings, green burials in natural preserves, or livestreamed memorials with guests attending via smartphone from across the globe.32 As a result, death care has shifted from a collective, institutional process to an individualized, and often privatized, consumer experience.

This diversification reflects broader cultural trends toward secularization, identity politics, and customization. As Americans continue to disaffiliate from organized religion, they often seek funerary practices that are spiritually meaningful without being doctrinally rigid.33 Likewise, as cultural narratives around gender, race, and sexuality have evolved, so too have expectations for death care. LGBTQ+ individuals, for example, increasingly demand services that recognize their identities and partnerships, especially when estranged from birth families.34 Some Jewish and Muslim communities advocate for the revival of traditional practices such as tahara (ritual washing) and immediate burial, while Indigenous and African American communities work to reclaim ancestral rites suppressed by centuries of colonialism and systemic racism.35 These developments complicate the idea of a single “American way of death” and highlight the cultural negotiations now intrinsic to modern death care.

Despite the increased availability of choice, access remains unequal, often dictated by geography, class, and legal infrastructure. While urban and progressive regions may offer aquamation, natural burial preserves, and green-certified funeral homes, rural or conservative areas may present only conventional options.36 Financial disparities are even more pronounced. A basic funeral with burial can cost upwards of $9,000, while even cremation—long seen as the low-cost alternative—can exceed $3,000 when combined with memorial services or upgraded urns.37 The rise of “direct cremation,” which skips formal rituals and costs as little as $500, reflects not only minimalist preference but also economic necessity. Moreover, pre-need funeral contracts, often marketed as financial planning, can sometimes be predatory or misleading, underscoring the consumer vulnerabilities that persist despite regulatory efforts. The Federal Trade Commission’s Funeral Rule, while helpful, remains inconsistently enforced, and many families still face pressure to purchase unnecessary services or products in the midst of grief.

Technology has also become a central force shaping the contemporary death care industry, both as a tool of personalization and a medium of mourning. Livestreamed funerals, online memorials, QR-coded gravestones, and “digital afterlife” platforms now allow for geographically dispersed grieving, virtual attendance, and even curated posthumous social media presences.38 This digital transformation has both democratized access to mourning and raised new ethical questions about privacy, permanence, and commodification. Meanwhile, tech start-ups have entered the space with apps for death planning, estate organization, and grief counseling, often targeting millennials and Gen Z with sleek interfaces and minimalist aesthetics. These generations, raised with digital fluency and often skeptical of institutional authority, are redefining what it means to die “well”—favoring authenticity, transparency, ecological consciousness, and emotional integrity over inherited ritual or tradition.

The current American death care system stands at a crossroads of continuity and disruption. Traditional funeral homes remain active, especially in smaller communities and among older populations, but they now coexist with green burial guides, death doulas, home funeral facilitators, and algorithm-driven planning platforms. The industry is simultaneously entrenched and in flux, with innovation driven not only by market demands but also by shifting social values.39 Americans are confronting death more consciously, and in some cases, more courageously—seeking not to deny mortality but to shape its rituals to fit a rapidly evolving world. Yet the enduring challenge remains: how to balance the demands of a market-driven system with the deeper needs for dignity, justice, ritual, and memory. As the fragmentation of death care continues, so too does the opportunity to remake it—not just as an industry, but as a mirror of what we most value in life.

Conclusion

The history of death care in the United States is not merely a tale of evolving technique or commercial growth. It is a chronicle of cultural values in flux—of the tension between community and commerce, nature and science, reverence and regulation. As Americans navigate the complexities of dying in a fragmented yet hyper-modern society, the question remains not just how we care for our dead, but what such care reveals about how we live. Whether through ritual, reform, or resistance, the care of the dead is ultimately a reflection of the living. And in remembering that, we are called—again and again—not only to reckon with mortality, but to reimagine the human legacy we leave behind.

Appendix

Endnotes

- David E. Stannard, The Puritan Way of Death: A Study in Religion, Culture, and Social Change (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 45–48.

- Allan I. Ludwig, Graven Images: New England Stonecarving and Its Symbols, 1650–1815 (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1966), 32–37.

- Blanche Linden-Ward, Silent City on a Hill: Landscapes of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1989), 14–18.

- Erik R. Seeman, Death in the New World: Cross-Cultural Encounters, 1492–1800 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 89–94.

- Karin J. Bohleke, “Mourning and Sentiment in Early America: Gloves, Garb, and the Grave,” Dress 32, no. 1 (2005): 29–41.

- Gary Laderman, The Sacred Remains: American Attitudes Toward Death, 1799–1883 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), 11.

- James J. Farrell, Inventing the American Way of Death, 1830–1920 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1980), 26–30.

- Gary Laderman, Rest in Peace: A Cultural History of Death and the Funeral Home in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 22–24.

- Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Knopf, 2008), 180–185.

- Thomas W. Laqueur, The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 382–385.

- Charles O. Jackson, American Funerals: Social and Religious Aspects (Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1977), 91.

- Clifton D. Bryant, “The Undertaking Profession and the Social Function of Funerals,” Death Studies 1, no. 4 (1977): 399–417.

- Philip Alcabes, Dread: How Fear and Fantasy Have Fueled Epidemics from the Black Death to Avian Flu (New York: PublicAffairs, 2009), 72–75.

- Mitford, Jessica. The American Way of Death (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963), 18–22.

- Farrell, Inventing the American Way of Death, 162-165.

- Laderman, Rest in Peace, 73-78.

- Thomas Lynch, The Undertaking: Life Studies from the Dismal Trade (New York: W. W. Norton, 1997), 154–157.

- Philippe Ariès, The Hour of Our Death (New York: Knopf, 1981), 601–608.

- Laqueur, The Work of the Dead, 388-390.

- Mitford, The American Way of Death, 3-18.

- U.S. Federal Trade Commission, “Complying with the Funeral Rule,” last modified 2020, https://www.ftc.gov.

- Stephen Prothero, Purified by Fire: A History of Cremation in America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 165–170.

- Suzanne Kelly, Greening Death: Reclaiming Burial Practices and Restoring Our Tie to the Earth (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), 21–25.

- Prothero, Purified by Fire, 202-205.

- Laderman, Rest in Peace, 129-132.

- National Home Funeral Alliance, “About Us,” accessed May 20, 2025, https://www.homefuneralalliance.org.

- Kelly, Greening Death, 72-78.

- Green Burial Council, “History and Mission,” accessed May 20, 2025, https://www.greenburialcouncil.org.

- Caitlin Doughty, Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematory (New York: W. W. Norton, 2014), 88–92.

- Abby Schwartz, “The Rise of the Digital Afterlife: Technology and the Future of Grief,” Death Studies 44, no. 6 (2020): 345–359.

- Caitlin Doughty, Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?: Big Questions from Tiny Mortals About Death (New York: W. W. Norton, 2019), 112–115.

- Schwartz, “The Rise of the Digital Afterlife,” 345-349.

- Robert Wuthnow, After Heaven: Spirituality in America Since the 1950s (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 175–179.

- Elizabeth A. Wheeler, “Queering Death: LGBTQ+ Perspectives on End-of-Life Care,” Mortality 23, no. 4 (2018): 345–362.

- Kami Fletcher and Tamara Lanier, eds., Till Death Do Us Part: American Ethnic Cemeteries as Borders Uncrossed (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2020), 63–85.

- Kelly, Greening Death, 141-143.

- National Funeral Directors Association, “General Price List Median Costs,” accessed May 25, 2025, https://www.nfda.org.

- Tony Walter, “New Mourning: Grief in the Digital Age,” Social Research 78, no. 1 (2011): 289–314.

- Gary Laderman, Don’t Think About Death: A Memoir on Mortality (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2022), 102–108.

Bibliography

- Alcabes, Philip. Dread: How Fear and Fantasy Have Fueled Epidemics from the Black Death to Avian Flu. New York: PublicAffairs, 2009.

- Ariès, Philippe. The Hour of Our Death. Translated by Helen Weaver. New York: Knopf, 1981.

- Bohleke, Karin J. “Mourning and Sentiment in Early America: Gloves, Garb, and the Grave.” Dress 32, no. 1 (2005): 29–41.

- Bryant, Clifton D. “The Undertaking Profession and the Social Function of Funerals.” Death Studies 1, no. 4 (1977): 399–417.

- Doughty, Caitlin. Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematory. New York: W. W. Norton, 2014.

- Farrell, James J. Inventing the American Way of Death, 1830–1920. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1980.

- Faust, Drew Gilpin. This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. New York: Knopf, 2008.

- Fletcher, Kami, and Tamara Lanier, eds. Till Death Do Us Part: American Ethnic Cemeteries as Borders Uncrossed. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2020.

- Green Burial Council. “History and Mission.” Accessed May 20, 2025. https://www.greenburialcouncil.org.

- Jackson, Charles O. American Funerals: Social and Religious Aspects. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1977.

- Kelly, Suzanne. Greening Death: Reclaiming Burial Practices and Restoring Our Tie to the Earth. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.

- Laderman, Gary. The Sacred Remains: American Attitudes Toward Death, 1799–1883. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

- Laderman, Gary. Don’t Think About Death: A Memoir on Mortality. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2022.

- Laderman, Gary. Rest in Peace: A Cultural History of Death and the Funeral Home in Twentieth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Laqueur, Thomas W. The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Linden-Ward, Blanche. Silent City on a Hill: Landscapes of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1989.

- Ludwig, Allan I. Graven Images: New England Stonecarving and Its Symbols, 1650–1815. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1966.

- Lynch, Thomas. The Undertaking: Life Studies from the Dismal Trade. New York: W. W. Norton, 1997.

- Mitford, Jessica. The American Way of Death. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963.

- National Funeral Directors Association. “General Price List Median Costs.” Accessed May 25, 2025. https://www.nfda.org.

- National Home Funeral Alliance. “About Us.” Accessed May 20, 2025. https://www.homefuneralalliance.org.

- Prothero, Stephen. Purified by Fire: A History of Cremation in America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

- Schwartz, Abby. “The Rise of the Digital Afterlife: Technology and the Future of Grief.” Death Studies 44, no. 6 (2020): 345–359.

- Seeman, Erik R. Death in the New World: Cross-Cultural Encounters, 1492–1800. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.

- Stannard, David E. The Puritan Way of Death: A Study in Religion, Culture, and Social Change. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

- U.S. Federal Trade Commission. “Complying with the Funeral Rule.” Last modified 2020. https://www.ftc.gov.

- Walter, Tony. “New Mourning: Grief in the Digital Age.” Social Research 78, no. 1 (2011): 289–314.

- Wheeler, Elizabeth A. “Queering Death: LGBTQ+ Perspectives on End-of-Life Care.” Mortality 23, no. 4 (2018): 345–362.

- Wuthnow, Robert. After Heaven: Spirituality in America Since the 1950s. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.20.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.