Medieval universities were neither wholly autonomous nor fully enslaved.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The emergence of the medieval university in the 12th and 13th centuries was one of the most transformative developments in Western intellectual history. These institutions, often centered in cathedral towns and burgeoning urban centers, became crucibles of scholastic thought, custodians of classical texts, and laboratories of theological and philosophical synthesis. Yet, despite their vital role in preserving and transmitting knowledge, medieval universities were anything but independent. They existed at the crossroads of secular and ecclesiastical power, navigating a treacherous terrain of papal dictates, royal edicts, and civic pressures. This essay explores the manifold ways in which political and religious forces suppressed, shaped, and sometimes silenced these early centers of learning.

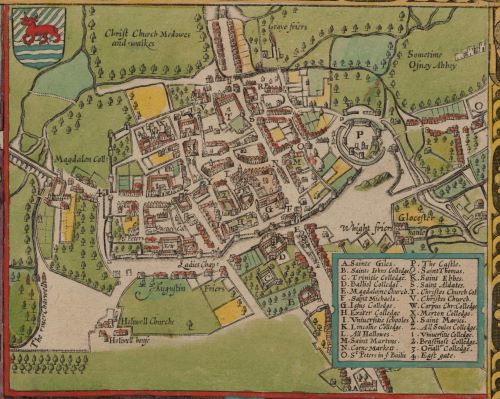

The Foundations: Born under Authority

From their inception, medieval universities were tethered to authority. The first great universities—Bologna, Paris, and Oxford—were established with explicit or implicit sanction from either the papacy or the crown. The University of Paris, for example, grew out of the cathedral school of Notre-Dame and was eventually granted autonomy under a papal charter.1 Similarly, Frederick Barbarossa’s Authentica Habita (1158), a foundational document for the University of Bologna, extended legal protections to students under imperial law.2

This entanglement created a paradox: while universities were meant to be spaces for inquiry and rational discourse, they operated under the ideological hegemony of Church and State. Their freedom to question—even within the narrow bounds of scholastic orthodoxy—could be revoked at any moment by the very powers that legitimized them.

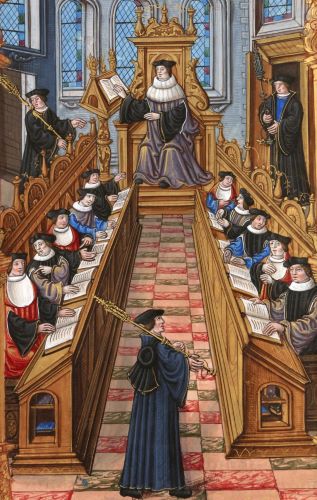

Papal Interference and Theological Censorship

The medieval university was above all a theological institution. Theology was the “queen of the sciences,” and most curricula culminated in its study. Yet as theology matured into an academic discipline, it often collided with ecclesiastical power, particularly when its practitioners pushed the boundaries of acceptable doctrine.

One of the most striking examples of papal suppression occurred at the University of Paris in 1277. Alarmed by the growing influence of Aristotelian philosophy—especially as interpreted by Muslim commentators like Averroes—Bishop Étienne Tempier, under papal pressure, issued a condemnation of 219 propositions.3 These included statements suggesting that the universe was eternal or that divine omnipotence was logically limited. The ban was sweeping, censoring not only Averroist ideas but also broader scholastic speculation. It was an attempt to enforce a rigid theological orthodoxy at a moment when university theologians were expanding the boundaries of Christian metaphysics.

While the condemnations were intellectually stifling in the short term, they also unintentionally stimulated new methods of argumentation. Scholars like Thomas Aquinas were forced to refine their positions more carefully, and the limitations inspired alternative approaches to understanding divine omnipotence and natural law.4 Still, the shadow of censure remained ever-present, with excommunication or professional ruin awaiting those who ventured too far.

Royal Authority and Civil Intrusion

If the Church wielded the power of doctrinal suppression, monarchs employed a more worldly force: direct political control. Universities were often viewed by kings as breeding grounds for dissent or, conversely, as tools for reinforcing royal ideology.

The University of Paris Strike of 1229 is a seminal case. What began as a carnival brawl between students and locals escalated into a violent crackdown by the city’s authorities. In the aftermath, many students were killed, and the university went on strike—essentially ceasing instruction.5 It was not a mere student protest but a profound assertion of institutional autonomy. The university refused to resume its functions until it secured protection from the Crown and autonomy under papal authority. Ironically, this incident solidified the University of Paris’s independence from municipal control, but it also underscored how vulnerable universities were to the whims of secular power.

Elsewhere, suppression was more enduring. The University of Oxford, like its Parisian counterpart, often found itself in conflict with local authorities and the Crown. In the 14th century, Edward II and Edward III repeatedly intervened in university affairs, sometimes siding with students, other times with townspeople or clergy, depending on the political advantage.6 Universities could be temporarily closed, their faculties punished, or their privileges revoked when their activities clashed with royal interests.

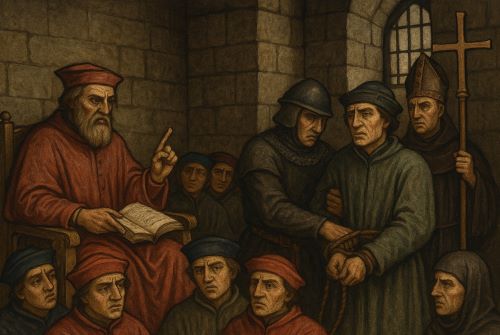

Heresy, Inquisition, and Intellectual Policing

No force exerted greater fear over the medieval intellectual world than the specter of heresy. As universities became hubs of theological discussion, they also became surveillance zones. Scholars had to walk a fine line between critical inquiry and heretical deviation. The establishment of the Inquisition in the 13th century intensified this tension.

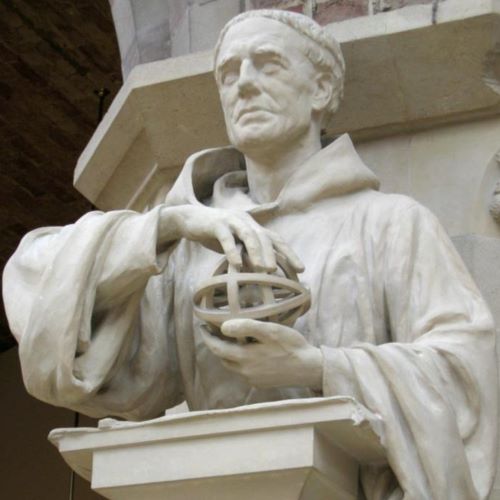

The case of Roger Bacon—a Franciscan friar and one of the earliest advocates of the empirical method—is illustrative. Though not officially condemned for heresy, Bacon was imprisoned by his own order, likely for his unorthodox views on theology and natural philosophy.7 His works, which emphasized observation and experimentation, were viewed with suspicion in an intellectual climate dominated by deductive reasoning rooted in theological authority.

More famously, John Wycliffe, a theologian at Oxford, openly challenged Church doctrines, including transubstantiation and the authority of the Pope. Though he died before he could be tried, his followers, the Lollards, were violently persecuted, and his teachings were banned from university curricula.8 Wycliffe’s fate demonstrated that the university could be both a pulpit and a scaffold.

The Legacy of Suppression: A Catalyst for Reform

Ironically, suppression often sowed the seeds of reform. The limits placed on thought created a dialectic tension that pushed some scholars to seek intellectual freedom elsewhere—outside the sanctioned frameworks of scholasticism or beyond the boundaries of the Church. The late medieval period witnessed an increasing number of university-educated clerics participating in proto-humanist movements, translating classical texts and advocating for more secular learning.9

By the time of the Renaissance and Reformation, universities had become both agents and victims of change. Reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin were themselves university men, schooled in the very traditions they would later challenge. Their ability to articulate theological and institutional critiques was a direct result of their education—but their persecution and exile showed that the medieval habit of suppressing dissent had not disappeared.

Conclusion: Between the Altar and the Throne

Medieval universities were neither wholly autonomous nor fully enslaved. They existed in a precarious balance—tolerated so long as they served the Church and the Crown, threatened whenever they did not. The suppression they endured—through censorship, persecution, and political interference—reveals a deep ambivalence in medieval society toward knowledge itself. Learning was prized but feared; inquiry encouraged but controlled.

And yet, from this crucible of constraint emerged some of the most enduring intellectual traditions of the Western world. The scholastic method, born under the gaze of inquisitors and monarchs, laid the groundwork for the secular academies and scientific revolutions to come. Suppression, paradoxically, became the midwife of liberation.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Olaf Pedersen, The First Universities: Studium Generale and the Origins of University Education in Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 47–49.

- Alan B. Cobban, The Medieval Universities: Their Development and Organization (London: Methuen, 1975), 43.

- Edward Grant, God and Reason in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 181–83.

- Ibid., 190–93.

- Gordon Leff, Paris and Oxford Universities in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries (New York: Wiley, 1968), 112–14.

- Lynn Thorndike, University Records and Life in the Middle Ages (New York: Columbia University Press, 1944), 98–101.

- R.I. Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society: Power and Deviance in Western Europe, 950–1250 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1987), 128–30.

- Ibid., 144–46.

- Pedersen, The First Universities, 155–57.

Bibliography

- Cobban, Alan B. The Medieval Universities: Their Development and Organization. London: Methuen, 1975.

- Grant, Edward. God and Reason in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Leff, Gordon. Paris and Oxford Universities in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. New York: Wiley, 1968.

- Moore, R.I. The Formation of a Persecuting Society: Power and Deviance in Western Europe, 950–1250. Oxford: Blackwell, 1987.

- Pedersen, Olaf. The First Universities: Studium Generale and the Origins of University Education in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Thorndike, Lynn. University Records and Life in the Middle Ages. New York: Columbia University Press, 1944.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.24.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.