How deeply human understanding of illness is shaped by cultural frameworks.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The medieval period was one of plagues, mysticism, and deep religiosity, in which disease was often understood not as a biological anomaly but as divine punishment or diabolical intervention. Among the strangest and most terrifying afflictions of the age was St. Anthony’s Fire, a condition now known to modern medicine as ergotism—a toxic reaction to alkaloids produced by the Claviceps purpurea fungus that infects rye and other cereals. The disease was named for the Order of St. Anthony, a monastic brotherhood that became renowned for its charitable work treating victims of the condition. Ergotism played a significant role not only in shaping medieval medicine and religious practice but also in revealing the porous boundaries between the natural and supernatural as perceived in the Middle Ages.

The Pathology of Ergotism

Ergotism is caused by the ingestion of grains, especially rye, contaminated by ergot, a fungal growth that replaces the developing grain with a dark, hardened mass called a sclerotium. These sclerotia contain ergot alkaloids such as ergotamine and lysergic acid, which act as potent vasoconstrictors and neurotoxins.1 There are two main types of ergotism: convulsive and gangrenous. Convulsive ergotism presents with symptoms such as muscle spasms, hallucinations, seizures, and psychosis—often mistaken in medieval accounts for demonic possession. Gangrenous ergotism, by contrast, involves the constriction of blood vessels leading to ischemia, necrosis, and ultimately the blackening and falling away of limbs.2

The particular susceptibility of rye to ergot, especially in damp conditions, made this a recurring hazard in parts of Europe, particularly in regions of France and Germany, where rye was a dietary staple among the peasantry. During years of poor harvest, contaminated grain was not discarded but consumed out of necessity, exacerbating outbreaks of the disease.

St. Anthony and the Antonites

The disease came to be known as “St. Anthony’s Fire” due to the intervention of the Hospitaller Order of St. Anthony, founded in 1095 at La-Motte-Saint-Didier in the Dauphiné region of France. The order was created in response to a major outbreak of ergotism and received papal approval to care for sufferers. The monks, known as the Antonites, wore the tau cross (T-shaped), which became a symbol associated with healing and protection against the disease. They established over 370 hospitals across Europe in the centuries that followed.3

The success of the Antonites in caring for ergotism patients was not necessarily due to medical knowledge but rather to their dietary interventions: by removing afflicted individuals from their usual food sources and placing them on a restricted diet of non-contaminated bread and fluids, they inadvertently eliminated the source of the poisoning. This led to miraculous recoveries in some cases, further reinforcing the idea that the disease was spiritual in origin and that healing came through divine intercession.

Cultural and Religious Interpretations

In a culture steeped in religious symbolism, the horrific symptoms of ergotism were interpreted through a theological lens. Burning sensations, blackened limbs, seizures, and madness were seen as manifestations of divine wrath or demonic affliction. That the victims sometimes seemed to recover miraculously after pilgrimage or prayer only deepened the association with the sacred. Pilgrimages to shrines of St. Anthony, such as those in Vienne and Freiburg, became popular among sufferers.4

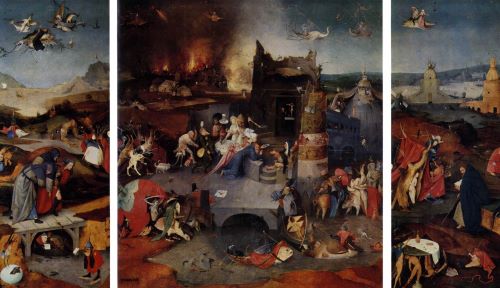

Iconography from the period often depicts St. Anthony alongside grotesque imagery of diseased bodies and hellish torment. In this sense, ergotism was not just a medical condition but a moral narrative about sin, suffering, and redemption. Religious orders like the Antonites offered more than food and shelter—they provided a framework for understanding and spiritualizing the disease.

The condition even found its way into art and literature. The paintings of Hieronymus Bosch, for example, show surreal and distorted figures that may be inspired by the hallucinations caused by ergot poisoning. Such representations contribute to the idea that disease in the medieval period was not just a physical state but a cosmic drama of good and evil played out on the human body.

Medical Legacy and Decline

With the gradual improvement of agricultural practices and the diversification of the European diet in the early modern period, major outbreaks of ergotism began to decline. Additionally, increasing awareness of the dangers of consuming certain grains in damp seasons may have contributed to preventative measures, even if the actual cause remained unknown until the 19th century.

It was not until the 19th century that the link between ergot and its toxic effects was scientifically confirmed. The isolation of ergot alkaloids led to the development of medical applications, including the use of ergotamine to treat migraines and to induce labor in childbirth. Ironically, the very fungus that caused medieval suffering became a source of medical innovation.

Yet the historical significance of ergotism in the medieval period lies not only in its physical toll but in its cultural and spiritual ramifications. It exemplifies how medieval people navigated the unknown, blending faith, ritual, and early empirical observation to make sense of disease.

Conclusion

St. Anthony’s Fire occupies a unique place in medieval history as a disease that blurred the boundaries between medicine and mysticism, between corporeal affliction and moral interpretation. In an age without germ theory or toxicology, people turned to saints, shrines, and spiritual orders to contend with what they could neither prevent nor explain. The Antonites’ compassionate care helped to alleviate suffering, but it also transformed ergotism into a story of faith and endurance. Today, the legacy of St. Anthony’s Fire reminds us how deeply human understanding of illness is shaped not only by science, but by the cultural frameworks in which suffering is made legible.

Appendix

Endnotes

- G. Barger, Ergot and Ergotism: A Monograph Based on the Dohme Lectures Delivered at Johns Hopkins University, 1931 (London: Gurney and Jackson, 1931), 5–8.

- Mary Kilbourne Matossian, Poisons of the Past: Molds, Epidemics, and History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), 44–47.

- Jane Slaughter, “The Medieval Hospitals of the Order of St. Anthony,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 18, no. 4 (1963): 385–87.

- Darien Shanske, “St. Anthony’s Fire and the Origin of Religious Hospitals,” Church History 74, no. 2 (2005): 296.

Bibliography

- Barger, G. Ergot and Ergotism: A Monograph Based on the Dohme Lectures Delivered at Johns Hopkins University, 1931. London: Gurney and Jackson, 1931.

- Matossian, Mary Kilbourne. Poisons of the Past: Molds, Epidemics, and History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

- Panati, Charles. Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things. New York: Harper & Row, 1987.

- Raymond, Martha. The Fires of the Saints: Disease and Healing in Medieval Religion. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996.

- Shanske, Darien. “St. Anthony’s Fire and the Origin of Religious Hospitals.” Church History 74, no. 2 (2005): 289–310.

- Slaughter, Jane. “The Medieval Hospitals of the Order of St. Anthony.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 18, no. 4 (1963): 381–402.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.25.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.