The human hand was a manuscript of the self, written in lines, mounds, and shapes.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Reading the Hand as Reading the World

Chiromancy, more commonly known today as palmistry, is the belief and practice that the human hand reveals insights into a person’s character, health, and fate. From the ridges of the palm to the length of the fingers, every contour was thought to be inscribed with cosmic meaning. Though typically relegated to the margins of esotericism and popular fortune-telling today, chiromancy in the ancient and medieval world enjoyed periodic episodes of scholarly and spiritual validation. Far from being an idle superstition of the ignorant, it was once taken seriously by educated individuals who situated it within broader frameworks of astrology, Aristotelian naturalism, and medieval medical theory. Here I explore the development of chiromancy from its early roots in ancient civilizations to its reception and eventual rejection in the intellectual ferment of the medieval period.

Ancient Origins: From India to Greece

The earliest known origins of chiromantic thought trace back to ancient India, where texts such as the Samudrika Shastra described the body, including the hand, as a microcosm of fate and character.1 This Indic science of bodily signs influenced Hellenistic thinkers via trade routes and cultural exchange through Persia and the Arab world. Greek and Roman sources—especially during the syncretic intellectual period following Alexander the Great—absorbed aspects of Indian cosmology, blending it with astrological determinism and physiognomy (the reading of character from facial features and body type).2

By the time of the Roman Empire, chiromancy had gained enough currency to be mentioned by writers like Pliny the Elder, and apocryphal texts were later attributed to Aristotle, who supposedly gifted a treatise on the subject to Alexander the Great.3 These attributions, while certainly fabricated, reflect the effort to confer authority upon palmistry by linking it to canonical figures. The idea was simple: if the body reflects nature, and nature follows the order of the cosmos, then the hand—so central to human activity—must contain intelligible signs of divine or natural design.4

The Transmission and Transformation of Chiromancy in the Islamic World

During the Islamic Golden Age (8th–13th centuries), chiromancy was absorbed into the broader corpus of Graeco-Arabic science. Arabic translations and commentaries on Aristotle, Galen, and Ptolemy often included discussions of physiognomy, astrology, and chiromancy, although chiromancy itself remained more suspect than its sister disciplines.5

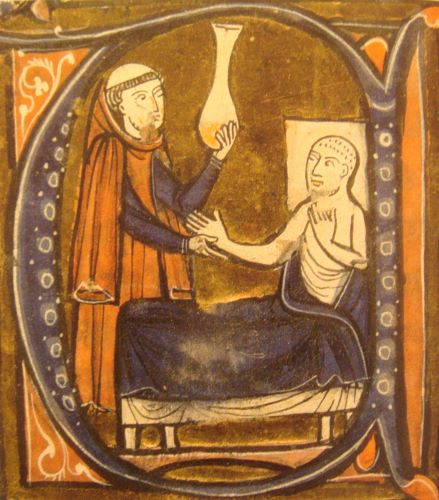

Practitioners in the Islamic world often reclassified chiromancy as a branch of medical diagnostics rather than pure divination, linking it to humoral theory.6 For instance, a cold and dry hand might indicate melancholia, while a warm and moist one suggested sanguinity. Such readings could then be used to advise treatments or temperaments. The scholar al-Razi (Rhazes) touches on physical diagnostics that overlap with chiromantic logic, even if he doesn’t explicitly endorse palmistry.7

By the time Latin Europe began to reabsorb classical and Arabic learning via Spain, Sicily, and the Crusader states, chiromancy was included among the strange new sciences that trickled into medieval intellectual life, often appended to manuscripts on astrology, alchemy, or medicine.8

Chiromancy in Medieval Europe: Between Science and Sin

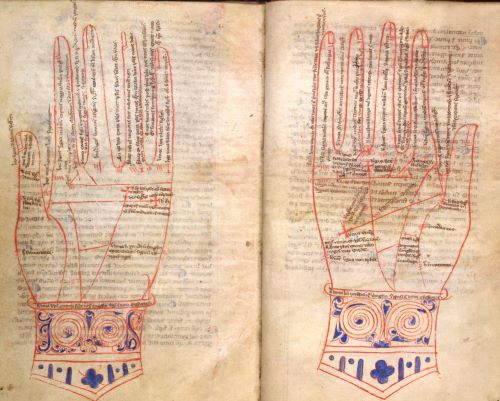

In medieval Europe, chiromancy was part of a broader return to occult naturalism during the 12th and 13th centuries—a period often referred to as the “Twelfth-Century Renaissance.”9 This era saw renewed interest in astrology, numerology, alchemy, and the micro-macrocosmic correspondences that defined medieval cosmology. Chiromancy reappeared in Latin texts, some of which were direct translations from Arabic sources or pseudo-Aristotelian treatises.10

One of the key appeals of chiromancy in this period was its fusion of the empirical and the esoteric. Like astrology, it claimed to be rooted in observation: careful comparison of hand shapes, line depths, and finger lengths could supposedly reveal personality, lifespan, and moral character. It also claimed predictive power—revealing potential futures, dangers, or tendencies—which made it both useful and dangerous in the eyes of the Church.11

Ecclesiastical authorities were deeply suspicious of divinatory practices. While astrology was tolerated when interpreted as a natural science (i.e., not negating free will), chiromancy was harder to defend, particularly as it drifted toward deterministic predictions and associations with folk magic.12 Despite this, some clerics and monks engaged with the practice—either out of curiosity or because they believed they could use it within a theological framework.13

Treatises such as the Chiromantia Aristotelis (falsely attributed to Aristotle) and anonymous compilations circulated among educated readers. These texts mapped the hand with astrological correspondences: the Mount of Venus beneath the thumb, the Mount of Jupiter beneath the index finger, and so on.14 The lines of the palm—Heart Line, Life Line, Head Line—were treated as indicators not only of health and temperament but of destiny.15

The Decline of Scholarly Chiromancy and the Rise of Popular Fortune-Telling

By the late Middle Ages and into the early Renaissance, chiromancy’s position in learned discourse declined sharply. The rise of humanism, with its emphasis on classical philology and empirical observation, pushed pseudoscientific disciplines like palmistry to the fringes.16 The Church’s condemnation also became more explicit—especially as chiromancy was increasingly practiced by itinerant fortune-tellers, Romani people, and those associated with “black arts” and witchcraft.17

Texts once read in monasteries now passed into the hands of folk practitioners, where chiromancy became more closely tied to superstition, entertainment, and the marketplace.18 Yet the underlying logic of chiromancy—its belief in the body as a readable text, its fusion of nature and fate—persisted. Even as formal medicine and science moved forward, palmistry remained resilient in popular imagination, especially in Early Modern Europe and beyond.19

Conclusion: The Enduring Allure of the Hand

Chiromancy is a classic example of a medieval pseudoscience that straddled the boundaries between medicine, astrology, theology, and folklore. Its persistence across cultures—from ancient India to Renaissance Europe—speaks to a deep human desire: to understand ourselves and our destinies through the tangible signs written on our bodies.20 In an age when the universe was believed to be a vast web of correspondences, the human hand was not merely a tool—it was a mirror of the cosmos, a manuscript of the self, written in lines, mounds, and shapes.

Though modern science has long dismissed palmistry as baseless, its historical journey reveals much about the intellectual tensions of past eras—between faith and reason, determinism and free will, body and soul. Chiromancy may no longer command the respect it once did among scholars, but its fingerprints linger in our metaphors, our cultural memory, and our fascination with the hidden language of the body.21

Appendix

Endnotes

- Nicholas Campion, Astrology and Cosmology in the World’s Religions (New York: NYU Press, 2012), 127.

- David Pingree, “The Indian Influence on Early Arabic Astrology,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 93, no. 3 (1973): 271–278.

- Fred Gettings, The Book of the Hand: An Illustrated History of Palmistry (London: Panther, 1973), 24.

- Lynn Thorndike, A History of Magic and Experimental Science, vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1923–1958), 252–55.

- Charles Burnett, Magic and Divination in the Middle Ages: Texts and Techniques in the Islamic and Christian Worlds (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1996), 82–86.

- Richard Kieckhefer, Magic in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 99.

- Ibid., 101.

- Pamela O. Long, Openness, Secrecy, Authorship: Technical Arts and the Culture of Knowledge from Antiquity to the Renaissance (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 187–88.

- Anthony Grafton, Magic and the Dignity of Man: Pico della Mirandola and His Heirs (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 44.

- Burnett, Magic and Divination, 93–95.

- Kieckhefer, Magic in the Middle Ages, 102.

- Paola Zambelli, White Magic, Black Magic in the European Renaissance (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 32–35.

- Thorndike, Magic and Experimental Science, 297–300.

- Gettings, Book of the Hand, 56–60.

- Ibid., 62.

- Stephen Clucas, “The Study of Nature and the Reinvention of Magic,” in The Cambridge History of Science, Volume 3: Early Modern Science, ed. Katharine Park and Lorraine Daston (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 535–548.

- Zambelli, White Magic, 48–51.

- Kieckhefer, Magic in the Middle Ages, 115.

- Long, Openness, Secrecy, Authorship, 191.

- Campion, Astrology and Cosmology, 129.

- Grafton, Magic and the Dignity of Man, 61–62.

Bibliography

- Burnett, Charles. Magic and Divination in the Middle Ages: Texts and Techniques in the Islamic and Christian Worlds. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1996.

- Campion, Nicholas. Astrology and Cosmology in the World’s Religions. New York: NYU Press, 2012.

- Clucas, Stephen. “The Study of Nature and the Reinvention of Magic.” In The Cambridge History of Science, Volume 3: Early Modern Science, edited by Katharine Park and Lorraine Daston, 535–548. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Gettings, Fred. The Book of the Hand: An Illustrated History of Palmistry. London: Panther, 1973.

- Grafton, Anthony. Magic and the Dignity of Man: Pico della Mirandola and His Heirs. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Kieckhefer, Richard. Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Long, Pamela O. Openness, Secrecy, Authorship: Technical Arts and the Culture of Knowledge from Antiquity to the Renaissance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

- Pingree, David. “The Indian Influence on Early Arabic Astrology.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 93, no. 3 (1973): 271–278.

- Thorndike, Lynn. A History of Magic and Experimental Science. 8 vols. New York: Columbia University Press, 1923–1958.

- Zambelli, Paola. White Magic, Black Magic in the European Renaissance. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.27.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.