The distinctions between hobos, tramps, and bums were not merely semantic.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Mobility and Identity in an Age of Upheaval

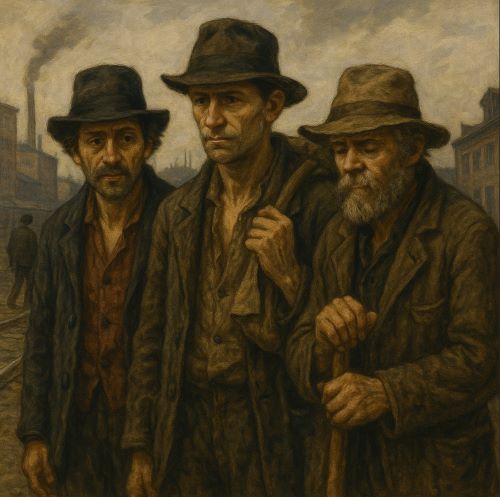

The industrialization of the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries gave rise to massive demographic shifts. Cities grew rapidly, railroads stitched the continent together, and waves of internal migration reshaped the American landscape. Among the more visible products of this transformation was the emergence of a transient population of itinerants—men (and occasionally women) who lived on the move, often outside the bounds of conventional employment and social respectability. While the general public often used terms like “hobo,” “tramp,” and “bum” interchangeably, those within these mobile communities drew sharp distinctions between them. Each label carried specific connotations of labor, dignity, and moral status, and their differences illuminate the ways in which Americans grappled with poverty, class, and work in a rapidly changing world.

The Hobo: A Worker on the Move

The hobo was a man of motion but also of labor. Emerging prominently after the Civil War and peaking in numbers during the Panic of 1893 and the Great Depression, hobos were migrant workers who traveled in search of seasonal or short-term employment. They followed harvests, worked on railroads, cut timber, dug ditches, or labored in steel mills and mines—whatever jobs could be found. They were not homeless in the modern sense so much as rootless, their homes defined by the rails and the road.

Hobos often traveled by freight train, a mode of transportation that became central to their culture. The expansion of the railroad network made it possible for itinerant laborers to traverse great distances in search of work. Over time, hobos developed their own code of conduct, symbols (known as hobo signs), and folk traditions. They organized conventions and maintained a subculture grounded in mutual respect and pragmatic survival.1 For many, hoboing was not a last resort but a chosen life of independence and movement—an American answer to economic precarity that preserved a measure of self-respect.

As Todd DePastino has noted, hobos saw themselves as the “vanguard of the working class,” temporarily displaced but still attached to the values of labor and personal autonomy.2 Their self-definition sharply contrasted with that of the tramp and the bum, whom they viewed with suspicion or disdain. In hobo culture, work was a badge of honor, and to hobo was to live a hard but dignified life on one’s own terms.

The Tramp: Wandering without Work

Where the hobo sought labor, the tramp was a non-worker by inclination, at least in popular lore and within the transient community itself. Tramps also traveled widely—often using the same railroads and routes as hobos—but were less willing or less able to work consistently. Some took the occasional job, especially when hungry or desperate, but their identity was tied less to labor and more to the act of wandering itself.

Contemporary accounts and reform literature often portrayed tramps as morally suspect: lazy, shiftless, even dangerous.3 Yet many tramps rejected the exploitative conditions of low-wage labor and adopted their lifestyle as a protest against industrial capitalism. Some tramps, especially in the 1870s and 1880s, were veterans of the Civil War or victims of economic collapse. Others suffered from alcoholism, mental illness, or social alienation. Their resistance to work could be read either as failure or as refusal, depending on one’s political lens.4

To hobos, however, the distinction was clear: a tramp was a loafer, someone who traveled but did not earn. This internal class division among the wandering poor reflected deeper tensions in American attitudes toward poverty—between those who could be redeemed through work and those who were seen as permanently deviant.

The Bum: Stationary and Idle

At the bottom of the hierarchy stood the bum—a figure often portrayed as stationary, degenerate, and wholly removed from the world of work. Unlike hobos or tramps, bums were urban dwellers who begged or scavenged and made no pretense of seeking employment. They were fixtures of city slums and back alleys, often associated with drunkenness and disease.

In the eyes of both society and their more mobile counterparts, bums represented failed manhood, the loss of initiative and independence.5 Hobos who lost the strength to work or the will to travel feared “bumming out”—becoming what they considered the most degraded form of the wanderer. This fear was deeply gendered; as American notions of masculinity were tied closely to labor and autonomy, the bum represented the erosion of both.

The term “bum” was thus the most derogatory, used to shame or dismiss those seen as beyond help or beneath respect. Reformers and journalists often conflated bums with all homeless men, contributing to moral panic and calls for stricter vagrancy laws.6

Law, Reform, and Cultural Representation

Despite the distinctions emphasized within transient communities, the broader society rarely made such nuanced judgments. All itinerant men—hobos, tramps, and bums—were vulnerable to vagrancy laws, police harassment, and incarceration. Cities sought to control their presence through ordinances that criminalized loitering, sleeping in public, or riding the rails without a ticket. These laws blurred the boundaries between economic need and criminality, and they were enforced unevenly and often brutally.7

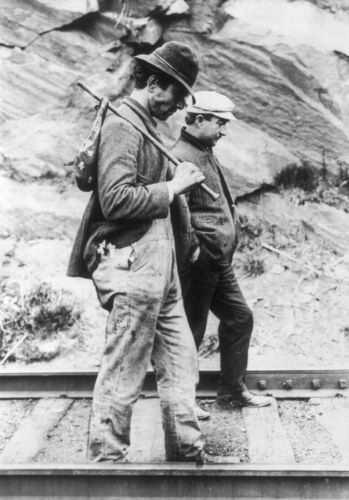

Reformers in the Progressive Era, many of whom saw poverty as a moral failing, tried to “reclaim” tramps through workhouses, religious missions, and charity institutions. Simultaneously, popular culture portrayed the hobo in contradictory ways. On the one hand, he was a romantic figure of the open road—a free spirit unshackled by materialism. On the other, he was a threat to order and productivity, a symbol of instability in the capitalist system. Charlie Chaplin’s “Little Tramp,” introduced in 1914, played on this ambiguity—comic, poor, harmless, and defiant all at once.8

Conclusion: Class, Choice, and the Politics of Poverty

The distinctions between hobos, tramps, and bums were not merely semantic—they reflected real social hierarchies, both among the transient poor themselves and in the eyes of the broader public. These terms marked different relationships to work, community, and identity. The hobo claimed the dignity of labor, the tramp embraced mobility without labor, and the bum became the cautionary tale at the end of the line.

In drawing these distinctions, Americans of the industrial age revealed their deeper anxieties about economic change, masculinity, and moral worth. The lines between choice and necessity, rebellion and failure, were constantly negotiated in the language used to describe the poor. Today, these terms have largely faded into historical memory, but their legacy lives on in debates about homelessness, poverty, and public space. They remind us that even within hardship, people define themselves—and are defined—through the stories they tell about labor, dignity, and survival.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Nels Anderson, The Hobo: The Sociology of the Homeless Man (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1923), 84–88.

- Todd DePastino, Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 34.

- Timothy Gilfoyle, A Pickpocket’s Tale: The Underworld of Nineteenth-Century New York (New York: W.W. Norton, 2006), 210–212.

- David Wagner, Checkerboard Square: Culture and Resistance in a Homeless Community (Boulder: Westview Press, 1993), 21.

- Anderson, The Hobo, 106.

- Kenneth Kusmer, Down and Out, on the Road: The Homeless in American History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 145–147.

- Michael Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse: A Social History of Welfare in America (New York: Basic Books, 1996), 93.

- DePastino, Citizen Hobo, 184.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Nels. The Hobo: The Sociology of the Homeless Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1923.

- DePastino, Todd. Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Gilfoyle, Timothy. A Pickpocket’s Tale: The Underworld of Nineteenth-Century New York. New York: W.W. Norton, 2006.

- Katz, Michael B. In the Shadow of the Poorhouse: A Social History of Welfare in America. New York: Basic Books, 1996.

- Kusmer, Kenneth L. Down and Out, on the Road: The Homeless in American History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Wagner, David. Checkerboard Square: Culture and Resistance in a Homeless Community. Boulder: Westview Press, 1993.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.02.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.