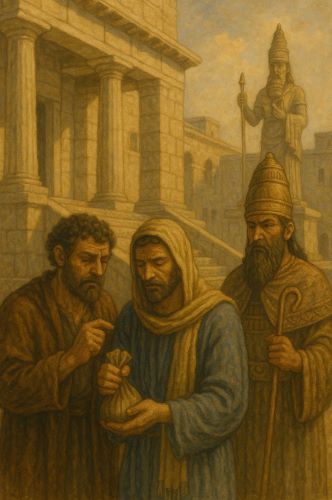

In the shadows of incense and stone, faith and exploitation coexisted.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Faith and Fraud in the Cradle of Civilization

In the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, Anatolia, and the Levant, temples were more than places of worship—they were political centers, economic engines, and cultural landmarks. Yet beneath the pious facade of incense and sacrifice, some temple institutions engaged in practices that blurred the lines between legitimate religious ritual and calculated deception. The blending of divine authority with economic power made temples ideal environments for manipulation. Whether through staged miracles, forged oracles, rigged divination, or financial exploitation, certain religious figures and institutions across the ancient Near East exploited belief for personal or institutional gain. These temple scams, while not necessarily representative of all religious practice, reveal the deep entanglement between power, performance, and piety in antiquity.

The Role of Temples in the Ancient Near East

Temples in ancient Near Eastern societies were more than sacred spaces; they functioned as centers of administration, education, landholding, and wealth. In Mesopotamia, ziggurat-temple complexes like those in Ur or Babylon housed not only priests but also scribes, merchants, artisans, and granaries.1 Egyptian temples, such as those at Karnak and Luxor, owned vast tracts of land and employed thousands. Temples collected taxes, recorded legal contracts, stored grain, and financed state rituals.

The economic might of temples depended on the perceived legitimacy of their connection to the divine. Priests were seen as intermediaries between mortals and gods, and their pronouncements carried tremendous authority. It is within this intersection of spiritual influence and material control that fraudulent activity could flourish—particularly in settings where literacy, ritual complexity, and social hierarchy limited public scrutiny.

Manipulated Oracles and Staged Miracles

One of the most widespread forms of religious deception involved the rigging of oracles and divinatory rituals. In many temples, divine will was revealed through omens, dream interpretation, astrology, or casting lots. These practices could easily be manipulated by priests or officials to serve political or financial agendas.

Lucian of Samosata, a second-century CE satirist from the Greco-Syrian city of Samosata, offers the most vivid account of a temple scam in his work Alexander the False Prophet. Though written much later than the primary era of Near Eastern antiquity, Lucian’s account draws on older traditions of false prophecy and cult fraud. He describes a man named Alexander who, claiming to channel the healing god Glycon, staged fake resurrections, planted questions among pilgrims, and used ventriloquism to fake divine speech.2 While exaggerated for satire, Lucian’s narrative resonates with earlier concerns about priestly trickery—especially as temples competed for donations and prestige.

Egypt provides material examples of such practices. Some temple sanctuaries employed mechanical devices—such as hidden levers, sound chambers, or steam-powered doors—to produce effects that amazed worshippers and enhanced the temple’s aura of the supernatural. Hero of Alexandria, writing in the first century CE, describes numerous temple “miracles,” including automatic doors that opened when altars were lit, wine that poured from statues, and serpents that appeared to move of their own accord.3 Though Hero was an inventor, his treatises suggest that similar contraptions had been used earlier to generate the appearance of divine action.

Divination for Sale: The Commercialization of Insight

The sale of divination and prophecy was another common source of exploitation. In Mesopotamia, temple scribes known as bārû (diviners) examined liver models of sacrificed animals, planetary positions, or the behavior of smoke and oil. These methods required years of training and access to esoteric knowledge preserved in temple libraries.4 As with any monopolized expertise, the potential for misuse was high.

Kings and nobles relied on diviners before battle, during omens of disaster, or in matters of succession. There is strong evidence that some bārû were bribed to produce favorable results or that their interpretations were selectively edited to support elite interests. The Enūma Anu Enlil, a Babylonian omen text, was used to divine the fates of rulers based on celestial movements, but the system was so complex and ambiguous that nearly any outcome could be justified.5 This interpretive flexibility made the manipulation of divine will a subtle but potent tool.

Similarly, the biblical prophets often denounced temple priests and court prophets who gave politically convenient oracles. The prophet Jeremiah, for instance, condemned “lying prophets” who proclaimed “peace, peace, when there is no peace” (Jer. 6:14), accusing them of distorting the divine message for gain.

Economic Exploitation and Temple Finances

Financial manipulation was an even more direct form of temple-based fraud. Temples frequently functioned as banks, collecting offerings, lending grain or silver, and leasing land. While these practices were often legitimate, they could also be exploitative.

In Mesopotamia, temple officials managed huge estates and often charged interest on loans of seed grain or livestock. Debtors who defaulted could lose their land, labor, or even their children to debt slavery.6 While not fraudulent per se, the combination of religious sanctity and economic power created conditions ripe for abuse—especially as priests wielded both spiritual authority and legal oversight.

There are also recorded instances of priests misappropriating offerings. In Hittite Anatolia, some temple inventories mention missing gold or livestock, prompting royal inspections. Egyptian records contain similar suspicions, particularly during periods of dynastic decline when temple power rivaled that of the pharaoh.7 The wealth of temples made them tempting targets for internal embezzlement and external appropriation alike. In response, some kings imposed reforms, such as the Neo-Assyrian king Esarhaddon, who regulated priestly roles and temple finances to curb abuse.

Religious Fraud and Popular Credulity

While priestly fraud operated in elite circles, religious scams also targeted ordinary people. Pilgrims often traveled great distances to receive healing or divine insight, bringing offerings of silver, grain, oil, or livestock. Some temples exploited these worshippers by charging exorbitant fees for oracles, selling fraudulent relics, or inventing new deities with local cults designed to attract donations.

Lucian again proves illustrative in mocking rural populations who fell prey to false seers and staged miracles. Though his tone is satirical, archaeological evidence supports the proliferation of local healing cults that promised fertility, recovery, or divine favor in exchange for gifts.8 Whether these offerings were accepted in good faith or manipulated depends on the transparency of temple operations—a subject we know less about due to the fragmentary nature of administrative records.

Conclusion: Sacred Performance and Institutional Trust

The power of temples in the ancient Near East derived not only from their connection to the divine but from their ability to stage that connection effectively. The line between sincere ritual and calculated performance was not always clear, and in a world where religion permeated every aspect of life, spiritual deception had real economic and political consequences. Temple scams were not universal, but they were symptomatic of a larger truth: religious institutions, like secular ones, were susceptible to the corrupting effects of wealth, secrecy, and power.

Understanding these historical episodes of religious fraud complicates the idealized image of ancient piety. It reveals a society where belief was deeply sincere but also vulnerable, and where institutions built to serve the gods could sometimes serve themselves. In the shadows of incense and stone, faith and exploitation coexisted—sometimes in harmony, and sometimes in conflict.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000–323 BC, 3rd ed. (Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, 2015), 98–101.

- Lucian of Samosata, Alexander the False Prophet, trans. A.M. Harmon (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1913), sec. 5–22.

- Hero of Alexandria, Pneumatica, trans. Bennet Woodcroft (London: Taylor Walton, 1851), 24–27.

- Jean Bottéro, Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia, trans. Teresa Lavender Fagan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 118–122.

- Francesca Rochberg, The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 59.

- M. T. Larsen, The Old Babylonian City of Ur (Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag, 1976), 137–139.

- John Baines and Jaromir Málek, Atlas of Ancient Egypt (New York: Facts on File, 1980), 90–92.

- Julia M. O’Brien, Challenging Prophetic Metaphor: Theology and Ideology in the Prophets (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2008), 46–48.

Bibliography

- Baines, John, and Jaromir Málek. Atlas of Ancient Egypt. New York: Facts on File, 1980.

- Bottéro, Jean. Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia. Translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

- Hero of Alexandria. Pneumatica. Translated by Bennet Woodcroft. London: Taylor Walton, 1851.

- Lucian of Samosata. Alexander the False Prophet. Translated by A.M. Harmon. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1913.

- Larsen, M. T. The Old Babylonian City of Ur. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag, 1976.

- O’Brien, Julia M. Challenging Prophetic Metaphor: Theology and Ideology in the Prophets. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008.

- Rochberg, Francesca. The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000–323 BC. 3rd ed. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, 2015.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.03.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.