More than just a con artist, the confidence man was a mirror held up to our society.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Age of Deception

The 19th century in America was a period of rapid transformation—economic expansion, westward migration, urban growth, and the emergence of new social and financial institutions. It was also an era of profound anxiety about trust. Amid the rise of markets and cities, Americans grappled with a world in which appearances could deceive and strangers had to be believed, if only temporarily, to conduct business or maintain social cohesion. Into this environment stepped a new kind of criminal: the confidence man. A master of charm, improvisation, and social engineering, the confidence man operated not by force but by gaining his victim’s trust—just long enough to exploit it. He became both a criminal figure and a cultural archetype, embodying broader fears about authenticity, capitalism, and the fragility of moral order in a moving society.

Origins of the Confidence Man

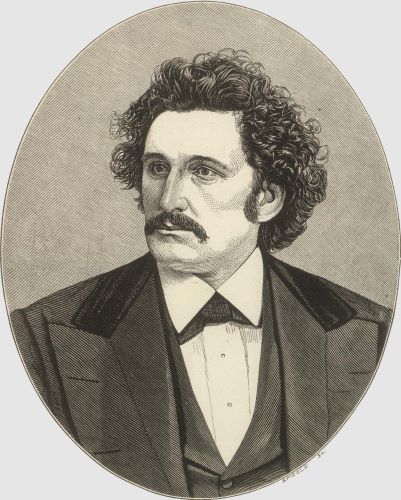

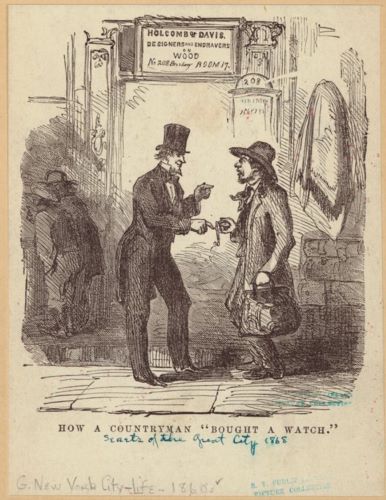

The term “confidence man” first entered public discourse in 1849 when newspapers reported the arrest of William Thompson, a well-dressed New Yorker who approached strangers and, through casual conversation and polished demeanor, asked, “Have you the confidence in me to lend me your watch until tomorrow?”1 To the astonishment of authorities, many gentlemen—believing themselves shrewd and worldly—obliged. Thompson would disappear, and the con was complete.

Thompson may not have invented the tactic, his case popularized the term “confidence man,” which quickly entered popular language and literature. The label stuck because it captured a distinctive approach: unlike pickpockets or burglars, the confidence man did not steal outright—he was given something, freely, under false pretenses. This made his crime a uniquely modern one, embedded in relationships of persuasion and performance rather than violence or stealth.

Techniques and Variants of the Con

Confidence men in the 19th century employed a wide range of schemes, many of which preyed on the expanding frontier economy, the rise of urban anonymity, and the proliferation of new financial instruments. Among the most common scams were:

- The short con, such as the “drop swindle,” where a confederate would “drop” a wallet or money in front of the mark and offer to share it if the mark put up collateral.

- The long con, involving elaborate setups with fake offices, actors posing as businessmen or bankers, and forged documents.

- Gold brick scams, in which marks were persuaded to buy what they believed was a bar of gold at a discounted price, only to discover it was filled with lead or worthless materials.2

- Fake lotteries, investment schemes, and land deals, exploiting the rapid expansion of finance, speculation, and westward settlement.

These scams thrived in spaces where social norms were ambiguous, such as train stations, hotels, new towns, and brokerage houses. The con artist relied not on the ignorance of the victim but on their greed, vanity, or desire to appear sophisticated. In this way, the victim was often made complicit in their own deception—a moral twist that fascinated and disturbed 19th-century observers.

The Confidence Man as Cultural Symbol

The confidence man was more than a criminal—he became a figure of cultural anxiety and literary exploration. His defining traits—fluid identity, persuasive charm, and moral ambiguity—reflected broader concerns about capitalism, urbanization, and social mobility.

No work captured this more than Herman Melville’s 1857 novel, The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade. Set aboard a Mississippi steamboat, the novel unfolds through a series of philosophical and financial cons, each more elusive than the last. The title character changes disguises, poses as a charitable solicitor, a clergyman, a patent medicine salesman, and more. Melville offers no clear resolution, instead presenting a world where truth and performance are indistinguishable—and where the confidence man may be a criminal, a savior, or both.3

Melville’s novel suggests that the confidence man is not an aberration but a product of American society itself—of its optimism, individualism, and obsession with self-reinvention. As literary critic Karen Halttunen observes, the con man became a “dark double” of the self-made man, using the same skills of adaptability and persuasion for illegitimate ends.4

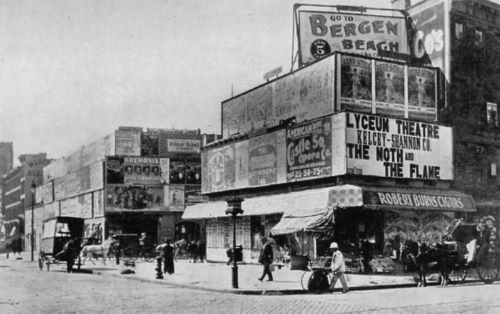

Con Men and the Rise of the City

The confidence man was uniquely suited to the growing cities of 19th-century America. In places like New York, Chicago, and New Orleans, the density and anonymity of urban life made deception easier. The massive influx of immigrants, rural migrants, and fortune-seekers created a population of people unfamiliar with local customs and eager to make fast money—ideal marks for confidence schemes.

Police records and newspapers from the period are filled with reports of swindles conducted in boarding houses, gambling dens, train depots, and saloons. The most skilled confidence men operated with accomplices and even bribed law enforcement to look the other way. They blurred the line between legitimate business and fraud—mirroring the gray zones of Gilded Age capitalism itself.

The New York Tribune warned readers in 1859 of “smooth-tongued gentlemen” who “live by their wits, prey on strangers, and travel under false names.”5 As cities expanded, so did the need for vigilance, for contracts, for identification papers—and for a police force that could recognize and prosecute deception, not just theft.

The Legal and Moral Response

Legally, confidence games posed unique challenges. Because victims technically “gave” their possessions to the perpetrator, prosecution required proof of intentional deceit, not just misfortune. This made many cons difficult to litigate. Moreover, victims were often reluctant to testify, out of shame or fear of appearing foolish.

Morally, the confidence man generated a blend of disgust and fascination. He was condemned in sermons and cautionary tales as a parasite on honest labor—but also admired, in some circles, for his cleverness and daring. He exemplified what historian T.J. Jackson Lears called “antimodernist” concerns—anxieties that traditional virtues of honesty and community were being replaced by spectacle, performance, and market ruthlessness.6

By the end of the century, as fraud became more professionalized in the form of corporate scams and stock manipulations, the confidence man gave way to a new breed of white-collar criminal. But his legacy persisted—in literature, in law, and in the American imagination.

Conclusion: The Business of Trust

The confidence man of the 19th century emerged at a time when trust was becoming transactional, when identity could be invented, and when belief itself became a form of currency. He thrived in a world where appearance could be mistaken for reality, and where the line between ambition and deceit was easily crossed.

More than a con artist, the confidence man was a mirror held up to society—revealing the contradictions of a nation that celebrated freedom but feared disorder, that worshipped self-reliance but feared self-invention. In studying his rise, we are reminded that every economy runs on belief—and that the boldest fraud is often built not on lies, but on the willingness of others to believe them.

Appendix

Endnotes

- “Arrest of the Confidence Man,” New York Herald, July 8, 1849.

- David W. Maurer, The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man and the Confidence Game (New York: Anchor Books, 1999), 45–52.

- Herman Melville, The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade (New York: Dix & Edwards, 1857).

- Karen Halttunen, Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830–1870 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982), 14–18.

- “Beware of Swindlers,” New York Tribune, October 19, 1859.

- T.J. Jackson Lears, Fables of Abundance: A Cultural History of Advertising in America (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 88–91.

Bibliography

- Halttunen, Karen. Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830–1870. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982.

- Lears, T.J. Jackson. Fables of Abundance: A Cultural History of Advertising in America. New York: Basic Books, 1994.

- Maurer, David W. The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man and the Confidence Game. New York: Anchor Books, 1999.

- Melville, Herman. The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade. New York: Dix & Edwards, 1857.

- “Arrest of the Confidence Man.” New York Herald, July 8, 1849.

- “Beware of Swindlers.” New York Tribune, October 19, 1859.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.03.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.