From Earth’s orbit to the farthest reaches of exploration, we’ve left behind a trail of cosmic clutter.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In the decades since Sputnik first pierced the atmosphere in 1957, humanity has been reaching ever deeper into the cosmos. We’ve orbited Earth, walked on the Moon, launched probes beyond the edge of the solar system, and established permanent robotic outposts on Mars. But in our quest for discovery, we’ve also left behind something far less noble: junk.

Space, once a pristine void, is now increasingly a cosmic dumping ground. From defunct satellites and rocket fragments spinning around the Earth to dead probes drifting silently in the interstellar dark, the remnants of our technological triumphs have accumulated into a new kind of pollution — one that threatens not only future space travel but the very safety of orbital infrastructure on which modern life depends.

A Halo of Trash Around the Earth

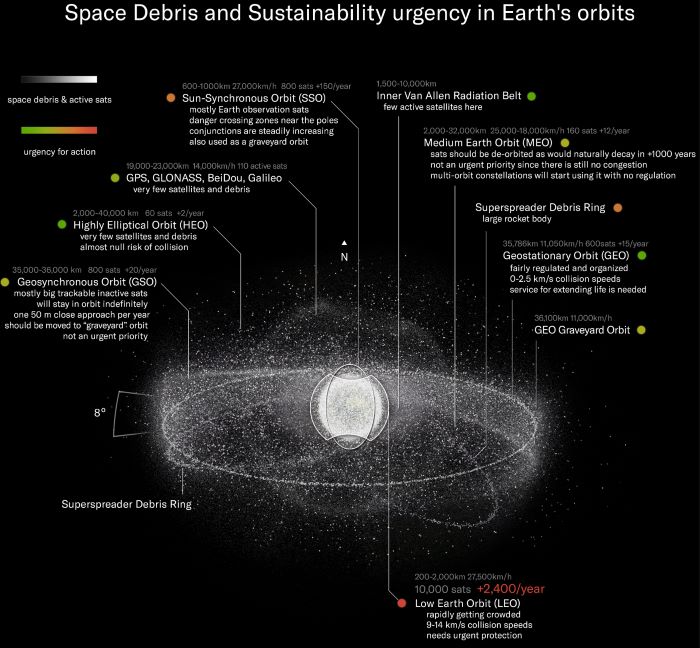

The most immediate and alarming space junk problem lies in Earth’s orbit. This artificial halo of debris is composed of thousands of defunct satellites, spent rocket stages, mission-related debris (like bolts, lens caps, and even a glove lost by an astronaut), and fragments created by collisions or anti-satellite weapon tests.

According to the European Space Agency (ESA), more than 36,000 objects larger than 10 cm are being tracked in orbit. Estimates place the number of particles between 1 and 10 cm at around 1 million, and those smaller than 1 cm at over 130 million. These aren’t harmless specs of dust — even a flake of paint traveling at orbital speeds (up to 17,500 mph) can do catastrophic damage.

The consequences are not hypothetical. In 2009, a defunct Russian satellite collided with an active U.S. Iridium communications satellite, creating thousands of new debris fragments. In 2007, China’s anti-satellite missile test shattered one of its own weather satellites, generating one of the largest debris clouds in history — and many of those pieces are still orbiting today.

The International Space Station (ISS) regularly performs evasive maneuvers to avoid debris, and spacecraft are designed with shielding to protect against micrometeoroid impacts. But the risk is growing, and many worry about a tipping point known as the Kessler Syndrome — a scenario in which cascading collisions make low Earth orbit (LEO) unusable for decades.

Junk beyond Earth’s Gravitational Grip

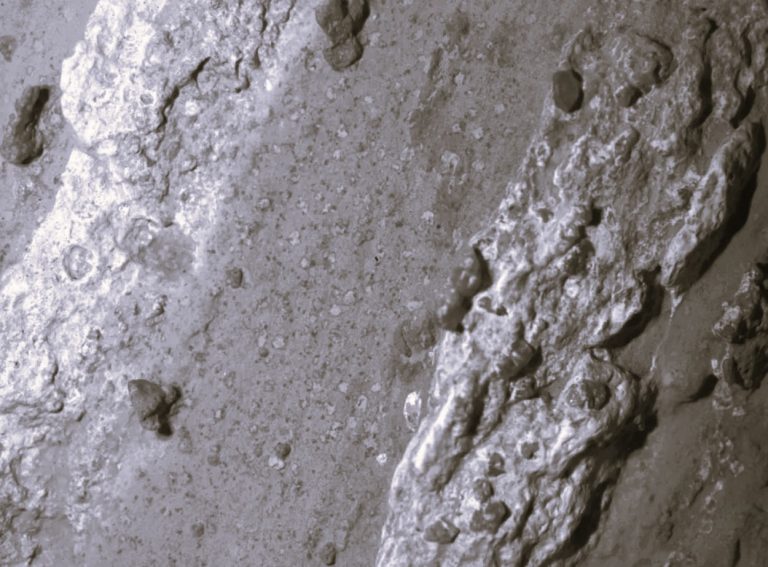

Earth orbit is only the beginning. Beyond our planet’s protective cocoon, the detritus of exploration is more dispersed but no less present. Mars has become something of a Martian museum of discarded human hardware — over a dozen landers, rovers, parachutes, heat shields, and crashed probes litter its dusty surface. The Moon, too, is a graveyard of spent modules, rover components, and even bags of astronaut waste dumped during the Apollo missions.

The outer solar system has its own share of human relics. The Voyager probes, Pioneer spacecraft, and New Horizons are all drifting quietly through interstellar space, long past their operational lives but still transmitting faint signals (or silent now, in the case of the Pioneers). These missions represent the golden age of space exploration, but they are also the most distant examples of human litter — frozen emissaries bearing plaques and golden records but no retrieval plan.

Even comets and asteroids have been touched by our techno-fingerprints. Missions like Japan’s Hayabusa and ESA’s Rosetta left hardware in orbit or on the surfaces of their target bodies. The samples they returned were invaluable — but they left behind broken components, crashed landers, and spent orbital stages.

The Tragedy of a Commons in Space

The problem with space junk is not merely physical; it is political and economic. Space is what economists call a “tragedy of the commons” — a shared resource with no universally enforced rules for its stewardship. Multiple countries and private companies operate independently, launching satellites and probes with minimal international coordination. And while new efforts are underway to clean up orbital debris — including concepts like space nets, harpoons, and magnetic tugs — most are still in experimental stages.

Worse, as space becomes more commercialized, the number of satellites is skyrocketing. Mega-constellations like SpaceX’s Starlink, Amazon’s Kuiper, and others promise to deliver global internet access but add tens of thousands of satellites to the mix — exponentially increasing the risk of debris generation.

Treaties like the 1967 Outer Space Treaty and the more recent Artemis Accords offer frameworks for cooperation, but they lack the teeth to enforce debris mitigation. And there’s no established plan for junk that’s already out there. While Earth-bound pollution has attracted environmental activism and legislation, space pollution remains an abstract concern for most of the public.

Cleaning Up the Cosmic Mess

There is, however, a growing consensus that action is needed — and soon. Agencies like NASA and ESA are developing debris removal missions, including ClearSpace-1, which aims to capture and deorbit a defunct satellite. Some satellite companies are designing craft with propulsion systems for end-of-life deorbiting or proposing “space traffic control” networks for better coordination.

Still, the problem is daunting. Removing even one large piece of debris costs millions of dollars, and there are tens of thousands to address. The technology exists, but the incentive structure does not — and unlike terrestrial trash, there are no garbage trucks in space.

A Wake-Up Call in the Void

Humanity’s technological ambition has always outpaced its foresight. We have reached for the stars with extraordinary creativity and courage, but with little regard for what we’ve left behind. Space junk is the shadow cast by our curiosity — a reminder that even our highest aspirations can produce unintended consequences.

The universe may be vast, but the space we actually use is surprisingly limited and increasingly cluttered. As we dream of lunar bases, Martian colonies, and asteroid mining, we must also contend with the very real threat that our past carelessness could jeopardize our future missions. Space was once the realm of poets and pioneers. It is becoming a landfill. Unless we change course, we may find ourselves not voyaging boldly into the final frontier, but tripping over our own trash on the launchpad.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.08.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.