By tracing how past rulers manipulated meaning, we gain sharper tools to recognize when the same sleights of hand are used today.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Spectacle of Power

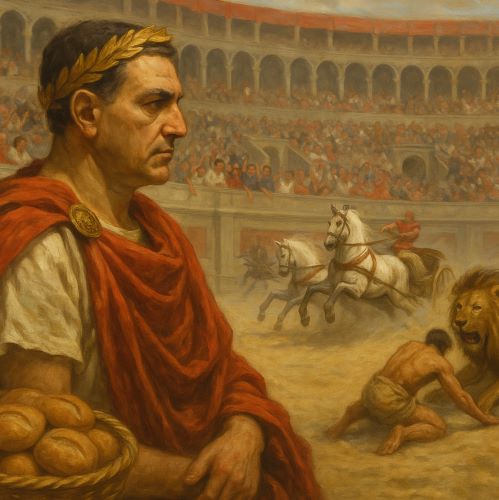

Roman emperors knew the value of distraction. With the provinces restless, the Senate increasingly symbolic, and economic inequality deepening, the answer from the imperial elite was rarely reform. Instead, it was entertainment. Gladiators fought, chariots thundered, and the crowds roared. Behind the spectacle, deeper fractures in the Roman state widened.

This practice was not unique to Rome. Across the ancient world, from Mesopotamian courts to Aztec temples, rulers leveraged culture and religion to distract, pacify, and manipulate. They employed myth and performance, curated outrage, and ritualized fear. Their tools may have differed in form, but their purpose was eerily consistent: maintaining elite power while minimizing resistance. What emerges is a pattern of engineered diversion — one that still echoes in the carefully manufactured culture wars of modern politics.

The Roman Formula: Panem et Circenses

The phrase “bread and circuses,” coined by the poet Juvenal, was not praise but condemnation. It described a Roman population lulled by food distributions and mass entertainment, oblivious to their declining civic agency. The Roman emperors institutionalized this dynamic with grim efficiency. By the time of Augustus, public spectacles were so essential to imperial legitimacy that games and festivals outnumbered actual legislative sessions.

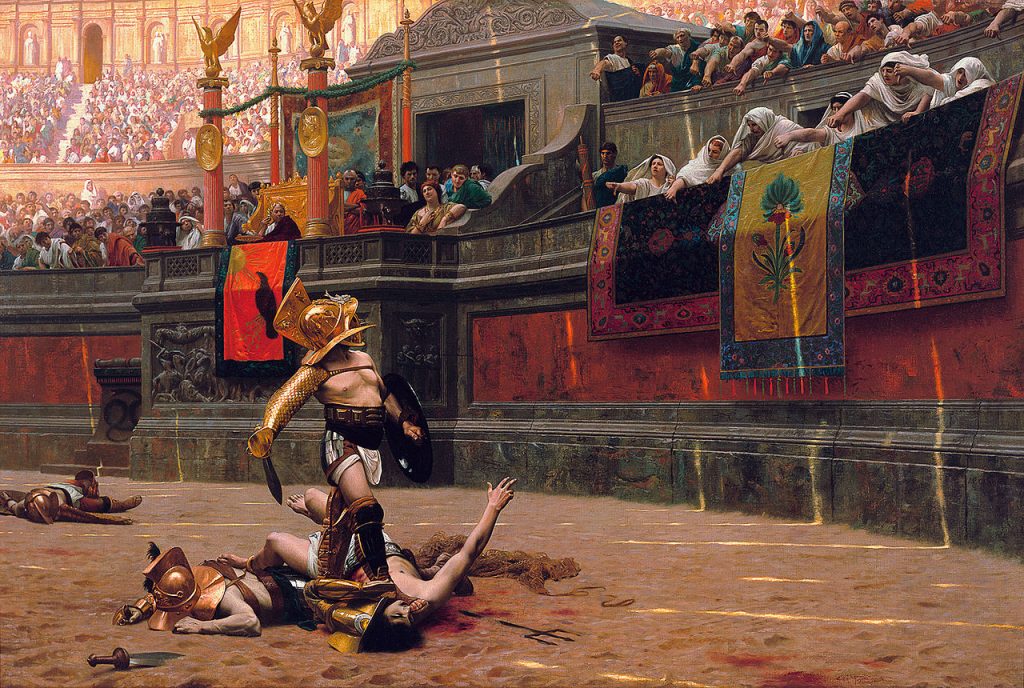

Crucially, these entertainments coincided with imperial crises. The Colosseum’s inauguration under Titus in 80 CE was paired with lavish spectacles despite Rome still reeling from the eruption of Vesuvius and a recent plague. A century later, Commodus used staged gladiatorial battles to distract from military failures and Senate resentment. The state, increasingly autocratic, substituted visibility for participation — citizens became spectators rather than stakeholders.

Roman elites also deployed outrage tactically. The persecution of Christians under Nero, for instance, redirected public anger after the Great Fire of 64 CE. Tacitus writes that Nero used the sect as a scapegoat to suppress rumors of his own guilt and redirect collective rage onto a convenient, foreignized minority.1

This was moral panic weaponized for survival. The Christians, already viewed as secretive and subversive, were easy to frame as threats to Roman order. The resulting persecution was brutal, but it also served a political function. The emperor’s enemies were not just silenced; they were consumed by public spectacle.

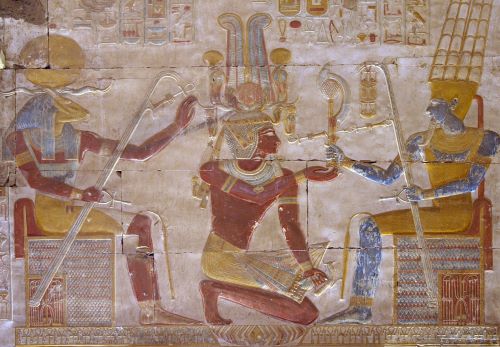

Divine Spectacle and Manufactured Consent in Egypt and Mesopotamia

In ancient Egypt, Pharaoh’s power was not merely political but cosmic. Kingship was sacralized through elaborate rituals, festivals, and monumental architecture that declared divine order. This ceremonial theater helped obscure the violence of conscripted labor, military campaigns, and grain hoarding by elites.

The Opet Festival in Thebes, for example, was a multi-day celebration that paraded the image of Amun through the city, reinforcing royal legitimacy.2 During periods of internal unrest or poor harvests, these festivals intensified. They were not just religious observances but orchestrated affirmations of the status quo.

In Mesopotamia, the Akitu (New Year) Festival served a similar function. The king was ritually humiliated, then restored in a reenactment of cosmic renewal that reaffirmed his divine right to rule.3 These rituals projected continuity even during breakdowns of governance. When famines or invasions loomed, the gods could be blamed, not the king — whose authority was theatrically “renewed.”

Cultural performance thus became a buffer against accountability. In both Egypt and Mesopotamia, elite control of symbolic meaning allowed for the redirection of discontent. Hunger and inequality were not policy failures; they were divine tests. And in many cases, dissent itself could be labeled impious.

Scapegoats and Ritual Violence in the Ancient Near East

Scapegoating was not always metaphorical. In several Near Eastern societies, actual individuals or animals were chosen to bear communal guilt and ritually expelled or sacrificed. The biblical Day of Atonement ritual, for example, involved placing sins on a literal “scapegoat” driven into the wilderness.4

This ritualized displacement of blame became political when rulers adapted it to manage unrest. Assyrian kings, facing rebellious provinces or omens of disaster, sometimes performed ritual substitutions — killing stand-ins for themselves to avert divine wrath.5 Whether symbolic or literal, the logic was the same: sacrifice a part to preserve the whole. The spectacle of justice, however arbitrary, became a means to reinforce order.

These practices fed into a larger ideology of controlled outrage. Public executions, purges of court officials, or religious expulsions were theatrical events, framing rulers not as perpetrators of instability but as restorers of harmony. This tactic persists in contemporary politics, where “tough on crime” posturing often substitutes for addressing root causes.

Manufactured Outrage and Moral Panic in Ancient Athens

Athens, despite its democratic structure, was not immune to elite manipulation of public opinion. In the wake of military or political setbacks, the Athenian assembly sometimes engaged in dramatic outbursts of moral panic, often fueled by prominent speakers.

The most famous example is the trial and execution of Socrates. Accused of corrupting the youth and disrespecting the gods, his real crime was likely political dissent during a time of instability following the Peloponnesian War.6 His trial was less about law than symbolic purification — a public spectacle to reinforce collective boundaries after Athens’ imperial trauma.

The use of ostracism — exile by popular vote — further reveals this dynamic. Citizens were encouraged to expel one prominent figure each year, not for specific crimes but for becoming “too powerful.”7 In effect, it was a pressure valve for popular anxiety, channeled through democratic theater. The crowd, not the court, became the judge. The result was less a check on tyranny than a performance of civic unity, often manipulated by elite factions.

Lessons Echoing Through Time

The patterns traced in ancient cultures feel unsettlingly modern. When today’s politicians ban books, demonize marginalized groups, or turn sporting events into patriotic rituals, they tap into ancient strategies of distraction. The machinery has changed, but the method endures.

Manufactured outrage is a tool that thrives in environments of inequality. It offers a false clarity amid complexity, a target for frustrations that might otherwise rise toward power itself. Spectacle, whether in Roman arenas or on cable news, soothes and inflames at once — and always serves someone’s purpose.

These ancient histories caution against assuming that public culture is neutral. Entertainment, religion, even law are often arenas of ideological contest, shaped to obscure deeper fractures. By tracing how past rulers manipulated meaning, we gain sharper tools to recognize when the same sleights of hand are used today.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Tacitus, Annals, 15.44.

- David O’Connor, “The Processions of Amun at Thebes,” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 85 (1999): 121–138.

- Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000–323 BC (Wiley-Blackwell, 2007), 151.

- Leviticus 16:10.

- Jack M. Sasson, “The Blood of the Substitutes,” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 36 (1984): 1–9.

- F. Stone, The Trial of Socrates (Anchor Books, 1989).

- Jennifer Tolbert Roberts, Athens on Trial: The Antidemocratic Tradition in Western Thought (Princeton University Press, 1994), 63–70.

Bibliography

- O’Connor, David. “The Processions of Amun at Thebes.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 85 (1999): 121–138.

- Roberts, Jennifer Tolbert. Athens on Trial: The Antidemocratic Tradition in Western Thought. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Sasson, Jack M. “The Blood of the Substitutes.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 36 (1984): 1–9.

- Stone, I. F. The Trial of Socrates. New York: Anchor Books, 1989.

- Tacitus. The Annals of Imperial Rome, translated by Michael Grant. New York: Penguin, 1956.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000–323 BC. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.15.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.