The language that cloaks privilege is often older than we realize, echoing through cathedrals and corporate boardrooms alike.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Gold in the Hands of God’s Chosen

The medieval world teetered between divine order and devastating inequality. Its political economy relied on a rigid hierarchy in which spiritual and noble elites amassed wealth at a scale unfathomable to the peasantry, whose survival often hinged on seasonal mercy and scraps of grain. This paradox, wherein those charged with moral and religious leadership thrived as others starved, did not go unnoticed by contemporary critics or later reformers. Yet for much of the Middle Ages, elite classes did not simply hoard in silence. They constructed elaborate theological and cultural narratives to sanctify their wealth and distance themselves from culpability. These justifications were neither uniform nor entirely cynical. They ranged from overt claims of divine favor to strategic performances of charity, and from apocalyptic warnings to the scapegoating of perceived outsiders.

Here I examine how the medieval nobility and clergy justified their material privilege amid systemic suffering, and how these narratives parallel the rhetorical strategies used by modern elites to resist economic redistribution. Just as billionaires today warn of “wealth flight” and philanthrocapitalism as alternatives to taxation, medieval lords and bishops crafted a sacred scaffolding around silver, power, and sin.

The Theology of Possession

Divine Ordination and the Feudal Order

Wealth in the medieval imagination was not simply a matter of possession. It was a symbol of divine election. The feudal system, with its layers of obligation and reciprocity, was often presented as a natural and God-given structure. From the writings of Isidore of Seville in the early seventh century to the canon lawyers of the twelfth, the ordering of society into those who prayed, those who fought, and those who worked was treated not as a social construction but a sacred inheritance.1

To challenge this order was not only a political threat but a theological offense. Clerics and aristocrats alike invoked the Great Chain of Being to portray social inequality as cosmic stability. The Lord’s blessing, they argued, was evident in the abundance held by the few. Wealth was not merely permitted by God; it was a sign of His favor. This doctrine, inherited from Augustine’s uneasy reflections on providence and sharpened by Aquinas’s measured approval of private property, offered the upper classes a moral shelter.

The Problem of Greed, Rewritten

Yet the medieval Church also condemned avarice. The Gospels were unequivocal in their warnings: “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter heaven”.2 To reconcile wealth with holiness required theological ingenuity. Monastic thinkers like Bernard of Clairvaux emphasized the intention behind possession. Wealth held for the benefit of the Church or the poor could be sanctified. The sin was not wealth itself but disordered desire.

This subtle shift allowed bishops and abbots to live in splendor while preaching poverty. Cathedrals rose from peasant tithes, and the sacred liturgy unfolded in gold-threaded vestments. Meanwhile, ascetic figures who genuinely embraced poverty, such as Francis of Assisi, became exceptions that proved the rule. Their radicalism was admired but not widely imitated. The Church became adept at absorbing its own critics — sanctifying them, canonizing them, and thereby neutralizing them.

Charitable Spectacle and Sacred Theater

Almsgiving as Redemption

Public charity emerged as a critical tool in the moral economy of wealth. The giving of alms was not merely an act of compassion but a performance of righteousness. Nobles funded hospitals and monasteries not only to aid the poor but to cleanse their sins, secure their legacy, and display their piety. This was not hidden generosity but highly visible philanthropy.

The medieval “economy of salvation” tied spiritual merit to acts of giving. Chronicles of noble lives, such as the Gesta Francorum, often dwelled on the patron’s donations as much as their battles.3 Testamentary donations, carved in stone or recited in song, elevated the benefactor’s soul and reinforced their social dominance. The poor, in this script, played the role of intercessors. Their prayers for the dead became part of the elite’s spiritual capital.

This dynamic resembled a transactional relationship. The donor gained absolution; the recipient was expected to express gratitude. In effect, the suffering of the poor was repurposed as an opportunity for elite virtue.

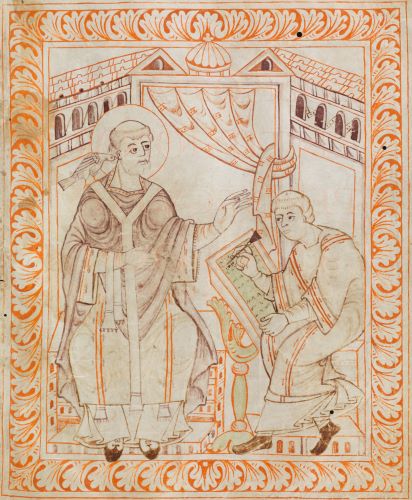

Saints in Silk

The cult of saints also provided a vehicle for elite moral laundering. By aligning themselves with local saints, funding shrines, or endowing relics, wealthy patrons embedded their identity within the sacred. Kings commissioned hagiographies in which their reigns were depicted as extensions of divine will, while wealthy widows sponsored abbeys in their family names.

These acts were not empty gestures. They were cultural tools that rewrote inequality as intercession. The saint’s grace — and by proximity, the donor’s — was said to bring healing, fertility, and protection to the land. The peasantry, encouraged to venerate these sites, were invited into a sacred economy whose gatekeepers were also its chief beneficiaries.

Scapegoats and Suffering: Redirecting Blame – Jews, Heretics, and the Myth of Moral Decay

When wealth inequality became too stark to ignore, or when famine and plague revealed the fragility of divine favor, elites often shifted attention toward supposed enemies within. Jewish communities in particular were frequent targets. Accusations of ritual murder, host desecration, and well poisoning surged during economic downturns.4 These fabrications allowed Christian elites to redirect social resentment away from themselves and onto marginalized others.

Heretical sects, such as the Cathars, were similarly demonized not only for their theology but for challenging the economic status quo. Their calls for apostolic poverty and rejection of ecclesiastical hierarchy threatened to unravel the carefully spun tapestry of sacred wealth. The Albigensian Crusade, under the guise of doctrinal correction, also served to reassert clerical and noble dominance.

In these campaigns of scapegoating, suffering was explained not as a consequence of hoarded abundance but as divine punishment for internal corruption. The powerful thus retained their claim to divine legitimacy by pointing outward.

Echoes in the Present

The medieval framework for justifying inequality did not vanish with the Renaissance. It evolved. Modern elites may no longer claim divine ordination, but the rhetoric of necessary inequality, benevolent wealth, and outsider blame endures.

Philanthropy now functions in many ways like medieval almsgiving. Billionaires fund foundations, build universities, and host global summits, casting their wealth as enlightened stewardship. Meanwhile, critics are branded as radicals, destabilizers, or, in subtler terms, “divisive.”

The sanctification of capital has shifted from theology to technocracy, but the narrative architecture remains intact. Wealth must be defended, and its moral implications defused. In both medieval and modern contexts, suffering becomes background — a context for elite redemption rather than a cause for structural redress.

Conclusion: The Moral Architecture of Inequality

Medieval elites did not simply enjoy their wealth. They explained it, sanctified it, and defended it with layered arguments that fused theology, spectacle, and blame. Their success in doing so offers a cautionary tale.

Understanding how inequality is narrated is as important as measuring it. The language that cloaks privilege is often older than we realize, echoing through cathedrals and corporate boardrooms alike. Saints and sinners alike are summoned to speak — not always to tell the truth, but to preserve a world in which wealth needs no apology.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Isidore of Seville, Etymologiae, trans. Stephen A. Barney et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006); see also Georges Duby, The Three Orders: Feudal Society Imagined, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980).

- Matthew 19:24 (New Testament).

- Gesta Francorum, in The First Crusade: The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres and Other Source Materials, ed. Edward Peters (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998), 25–35.

- Jeremy Cohen, Living Letters of the Law: Ideas of the Jew in Medieval Christianity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 135–172.

Bibliography

- Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Theologica. Translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. New York: Benziger Bros., 1947.

- Augustine. The City of God. Translated by Henry Bettenson. London: Penguin Books, 2003.

- Bernard of Clairvaux. On Consideration. Translated by George Lewis. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1908.

- Chenu, Marie-Dominique. Nature, Man, and Society in the Twelfth Century. Translated by Jerome Taylor and Lester K. Little. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968.

- Cohen, Jeremy. Living Letters of the Law: Ideas of the Jew in Medieval Christianity. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

- Duby, Georges. The Three Orders: Feudal Society Imagined. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

- Little, Lester K. Religious Poverty and the Profit Economy in Medieval Europe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1978.

- Moore, R. I. The Formation of a Persecuting Society: Authority and Deviance in Western Europe 950–1250. Oxford: Blackwell, 1987.

- Tierney, Brian. The Crisis of Church and State: 1050–1300. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.15.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.