To speak of a medieval surveillance state is anachronistic, but not entirely misplaced. Though decentralized and diffuse, the instruments of control were real.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Myth of Medieval Openness

To the modern imagination, the medieval world often appears as a landscape of porous borders and unregulated movement, a place where pilgrims wandered freely, merchants crossed kingdoms in search of trade, and fugitives vanished into forests untouched by state control. Such a vision bears some truth, but it is deeply misleading. Though lacking the biometric systems, passport regimes, and algorithmic watchtowers of our contemporary surveillance state, medieval societies cultivated intricate, deeply embedded systems of observing and managing human mobility.

These were not surveillance states in the Foucauldian sense. There were no panopticons, no centralized bureaucracies parsing citizen profiles. Yet power still watched. It watched not through cameras, but through people. Through village rumor, religious obligation, city gatekeepers, roving inquisitors, and ritualized performances of identity. In monasteries and market towns, across borderlands and pilgrimage routes, movement was both permitted and policed. The act of crossing space in the Middle Ages was rarely without oversight, formal or informal, visible or unseen.

Here I explore the myriad ways medieval polities and ecclesiastical institutions developed techniques of mobility control. It considers not only the surveillance of the body, but of the soul; not only the exclusion of strangers, but the inscription of identity through document, dress, language, and ritual. The aim is to rethink medieval governance not as blind to movement, but as attuned to its dangers and possibilities.

Gateways and Gatekeepers: City Walls as Control Apparatus

The walls of medieval cities were not merely defensive structures; they were regulatory mechanisms. Gates punctuated the perimeter not only as military choke points but as controlled apertures through which human traffic could be scrutinized and filtered. Urban entrance was often contingent on recognition. A traveler known to the porter or bearing letters of introduction might pass unmolested. An unknown figure, lacking such credentials, risked interrogation or denial.

In cities like Florence and Lübeck, local statutes empowered guards or elected officials to question entrants about their origin, purpose, and duration of stay.1 Some cities required a temporary lodging permit or registration at specific inns, especially for foreigners. While enforcement was uneven, the system reveals a conceptual framework of controlled permeability, where the movement of persons into the civic body was seen as a potential vector for disorder, disease, or dissent.

Markets and fairs further complicated this system. Special exemptions were often granted to merchants during these events, loosening border restrictions in the name of commerce. Yet even then, town records show heightened policing during such periods—both to prevent fraud and to manage the increased flow of outsiders.2 Surveillance was seasonal, pragmatic, and tied to economic rhythms.

The Pilgrim’s Gaze: Religious Scrutiny and Ritual Legibility

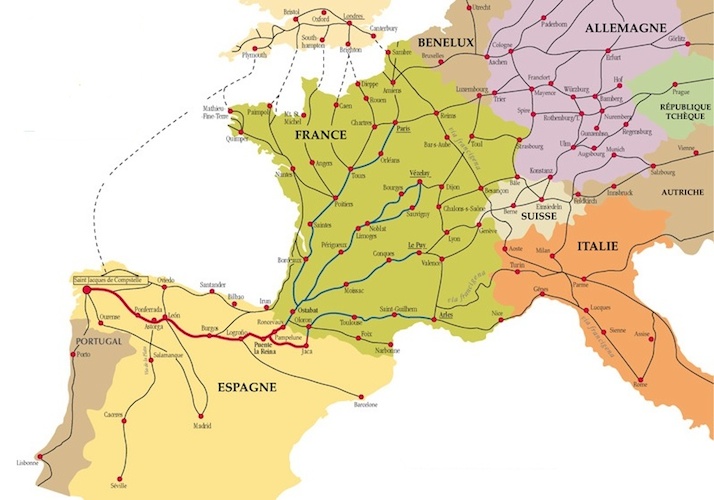

Pilgrimage routes across medieval Europe formed some of the most traveled corridors of the age, threading through mountains, cities, and across confessional boundaries. At first glance, these journeys might seem to exemplify a freedom of movement sanctioned by faith. But even here, movement was regulated, ritually, socially, and theologically.

Pilgrims were expected to carry visible symbols of their status: scallop shells for Compostela, palm branches for Jerusalem, badges for Canterbury. These tokens acted as both signs of piety and informal passports. A pilgrim without such emblems might be suspected of vagrancy or deceit.3 Indeed, vagrancy laws often exempted true pilgrims but penalized false ones, highlighting the importance of semiotic legibility to medieval surveillance.

Moreover, many pilgrimage destinations maintained registers or required letters of pilgrimage from ecclesiastical authorities. In 13th-century England, bishops often issued licenses granting permission to travel for spiritual reasons, sometimes noting the route and intended return.4 These documents served not only to control the spiritual narrative but to track human bodies in sacred motion.

Monasteries and hostels along pilgrimage routes also participated in this network of watchfulness. Their records, while spotty, suggest a communal memory of travelers. Tales of behavior, good or scandalous, circulated quickly, shaping local responses to future guests. The pilgrim may have sought divine encounter, but they did so under worldly eyes.

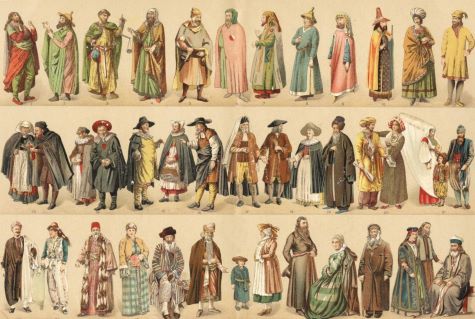

Marks of Belonging and Exclusion: Clothing, Language, and the Body

Control of mobility often required sorting insiders from outsiders, friends from strangers. In the absence of formal identification systems, medieval societies relied on embodied and performative markers to categorize those who crossed thresholds. These markers were deeply entangled with social identity, sometimes voluntary, sometimes imposed.

Sumptuary laws across Europe regulated who could wear what, encoding class distinctions into visible dress.5 Such laws served not only moral agendas but also helped officials and citizens alike make quick judgments about a person’s place. When travelers arrived in inappropriate clothing, too fine for their class, too foreign in cut, they drew suspicion.

Language and accent were equally diagnostic. Chroniclers frequently note the way a person “spoke strangely,” revealing foreignness through sound. In times of unrest, such speech could mark someone for exclusion or even violence. During outbreaks of plague or war, suspicion of outsiders intensified. Regions closed to itinerants, and local communities formed ad hoc patrols or demanded proofs of origin before offering aid.6

In extreme cases, the body itself was marked for identification. Criminals might be branded, ears cropped, or faces disfigured, acts of punitive inscription that made future concealment difficult. Jews, under various regimes, were required to wear distinctive badges or hats, marking them permanently as other, even when integrated into the urban landscape.7

Surveillance here was not passive. It was inscribed into social fabric, enacted through gesture, voice, and appearance. Visibility was not neutral; it was a technology of power.

Documents and Dossiers: Medieval Paperwork as Surveillance

Though lacking the bureaucratic scale of modern states, medieval polities made ample use of documentation to control movement. Letters of safe conduct, trade licenses, tax receipts, and ecclesiastical permissions were all instruments of identity verification and status management. While illiteracy limited their public function, these documents were legible to those who mattered: local officials, clergy, and elite intermediaries.

The Carolingians developed capitularies regulating who could travel and under what conditions, especially regarding merchants and soldiers.8 Later medieval kingdoms adopted more targeted paperwork. The English crown issued “protection writs” to subjects traveling abroad, which could be revoked in times of political suspicion. In the Hanseatic League, merchants carried certificates of origin and guild membership to access certain markets.

Perhaps most tellingly, inquisitors relied on detailed written confessions, witness statements, and mobility records to identify heretics. Papal registers tracked not only ecclesiastical correspondence but also movements of suspect individuals, often across diocesan lines. Paper became not only a record but a tool of containment.

The logic of surveillance thus began to crystallize in paperwork. Not omniscient, not infallible, but accumulative. A slow sediment of tracking that enabled future control.

Mobility as Threat and Resource: Political Contexts of Control

The regulation of movement was never neutral. Medieval surveillance systems emerged in response to specific threats: heresy, economic instability, warfare, plague, and rebellion. Each crisis heightened anxiety about the circulation of people and ideas.

In times of plague, cities like Venice and Dubrovnik pioneered quarantine measures, including isolation of travelers and health passports known as fedi di sanità.9 Though late medieval in origin, these early bio-surveillance mechanisms anticipated modern public health controls.

During periods of religious conflict, such as the Albigensian Crusade or the Hussite wars, church and crown alike intensified scrutiny of travelers. Heresy was seen not only as doctrinal error but as contagion carried by bodies. Travelers from suspect regions were interrogated, searched, and sometimes detained. Crossing a border was a theological risk.

At the same time, rulers recognized the economic and political necessity of movement. They courted foreign artisans, granted monopolies to traveling merchants, and welcomed exiles for strategic gain. Surveillance thus operated within a dialectic of suspicion and invitation, control and openness.

Medieval mobility regimes were not totalizing. They were fragmented, negotiated, and often bypassed. Yet their presence was felt, and their logic foreshadowed much that came later.

Conclusion: Rethinking the Medieval Surveillance State

To speak of a medieval surveillance state is anachronistic, but not entirely misplaced. Though decentralized and diffuse, the instruments of control were real. Cities watched their gates. Bishops tracked their flocks. Merchants bore papers. Pilgrims performed legitimacy. Strangers were scanned by eye, tongue, and dress. The state, such as it was, relied on networks of trust, suspicion, and local enforcement to regulate who belonged where.

What emerges is a world in which surveillance was intimate rather than distant, embodied rather than digital. It passed through the human sensorium (smell, sound, sight) and through rituals of recognition. And while it lacked the scale of modern systems, it shared their logic: that the movement of people is never simply logistical. It is political, spiritual, and dangerous.

In this light, the medieval world stands not as a pre-modern antithesis to our own, but as an early iteration of the same fundamental question: how does power see?

Appendix

Footnotes

- Nicholas Orme, Medieval Cities and Their Rulers (New York: Routledge, 2003), 87.

- Martha C. Howell, Commerce Before Capitalism in Europe, 1300–1600 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 122.

- Kathryn Rudy, Pilgrimage Badges and Pilgrim Souvenirs (London: British Museum Press, 2011), 34.

- Robert Bartlett, Why Can the Dead Do Such Great Things? (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 419.

- Ulinka Rublack, Dressing Up: Cultural Identity in Renaissance Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 41.

- Samuel Cohn, Cultures of Plague: Medical Thinking at the End of the Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 52.

- Kenneth Stow, Alienated Minority: The Jews of Medieval Latin Europe (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992), 103.

- Janet L. Nelson, Charles the Bald (London: Longman, 1992), 211.

- Ann G. Carmichael, “Plague Legislation in the Italian Renaissance,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 57, no. 4 (1983): 508.

Bibliography

- Bartlett, Robert. Why Can the Dead Do Such Great Things?. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013.

- Carmichael, Ann G. “Plague Legislation in the Italian Renaissance.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 57, no. 4 (1983): 508–515.

- Cohn, Samuel. Cultures of Plague: Medical Thinking at the End of the Renaissance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Howell, Martha C. Commerce Before Capitalism in Europe, 1300–1600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Nelson, Janet L. Charles the Bald. London: Longman, 1992.

- Orme, Nicholas. Medieval Cities and Their Rulers. New York: Routledge, 2003.

- Rublack, Ulinka. Dressing Up: Cultural Identity in Renaissance Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Rudy, Kathryn. Pilgrimage Badges and Pilgrim Souvenirs. London: British Museum Press, 2011.

- Stow, Kenneth. Alienated Minority: The Jews of Medieval Latin Europe. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.17.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.