The Spanish did not simply impose their will upon a static world. They disrupted a delicate ecological and social order whose disintegration, in turn, enabled their dominance.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Shadows on the Chinampas

In the long shadow of conquest, where obsidian blades gave way to iron, another sharper edge cut through the heart of Mesoamerica. This edge was invisible, without banners or riders, and it cleaved bodies and societies with equal indifference. The Nahua word cocoliztli, meaning “pestilence” or “plague,” enters the colonial record in the sixteenth century not as an isolated note of suffering but as a dirge echoing across a continent unmade.

Unlike the more widely known smallpox outbreak that followed shortly after Hernán Cortés’s arrival, the cocoliztli epidemics of 1545 and 1576 remain enigmas. They are obscure in popular memory yet arguably more devastating in demographic scale. With mortality estimates rivaling or exceeding those of the Black Death in Europe, these events do not merely represent biological catastrophe. They reflect, more profoundly, the collision of ecological fragility, imperial restructuring, and the spiritual dislocation that followed conquest. The plagues are not footnotes to conquest; they are its mirror, revealing a deeper truth about the kind of world that was born when another was undone.

Colonial Contact and Ecological Precarity

The arrival of Spaniards in the early sixteenth century did more than rupture political sovereignty. It unleashed a suite of transformations (biological, botanical, agricultural, and atmospheric) that rendered the post-conquest landscape more vulnerable to epidemic collapse. Prior to Spanish incursion, the Valley of Mexico supported dense urban populations with remarkable hydraulic engineering and chinampa agriculture. The city of Tenochtitlan itself was a marvel of ecological harmonization. Yet these systems, finely tuned over centuries, proved susceptible to disruption.

The introduction of European livestock compacted soils and disrupted irrigation. Deforestation for timber and grazing land altered local water tables and rainfall patterns. Moreover, the reduction of native populations through war and early disease meant the neglect of canals and terraces. These material shifts were not incidental. As geographer Elinor Melville has noted, the environmental degradation following conquest created ideal conditions for rodent and vector population surges.1 In this newly disordered world, disease did not merely arrive from without; it found fertile ground within.

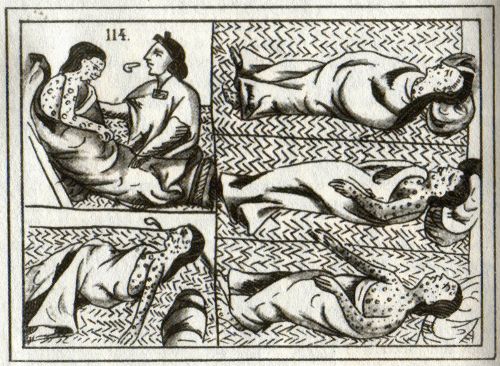

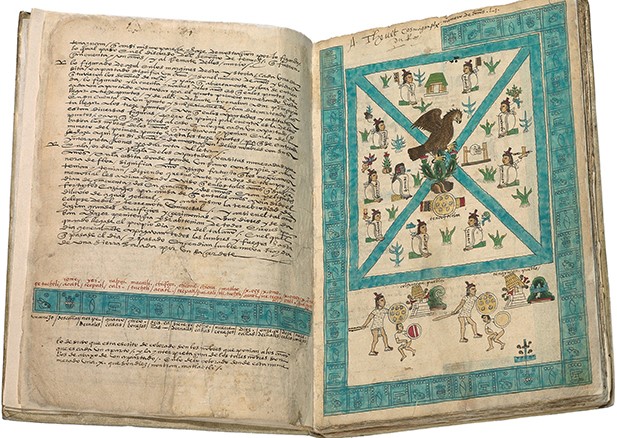

In 1545, a mysterious affliction spread across central and southern Mexico. Contemporary accounts described sudden onset of high fever, bleeding from orifices, blackened tongues, and rapid death within a few days.2 Spanish observers distinguished this illness from smallpox, measles, or typhus, suggesting a novel or emergent pathogen. Indigenous chroniclers such as those contributing to the Relaciones Geográficas were more vivid and spiritual in their descriptions. They understood the plagues as divine retribution, not only for collective sin but for the cosmic disorder inflicted by conquest.3

What Was Cocoliztli? Between Diagnosis and Narrative

Attempts to retroactively diagnose cocoliztli have yielded numerous theories, ranging from hemorrhagic fevers caused by arenaviruses to salmonella-induced septicemia. In 2018, a team of researchers analyzing ancient DNA from victims interred during the 1545 epidemic identified Salmonella enterica as a potential cause, specifically the Paratyphi C strain.4 Yet even this forensic breakthrough invites more questions than it answers. Why did this pathogen emerge so lethally at that particular moment? Why did it affect Indigenous populations disproportionately?

Here, narrative trumps pathogen. While scientific inquiry seeks a definitive biological origin, historical method requires attention to meaning. The cocoliztli epidemics were not solely biological events. They were cultural crucibles in which memory, theology, and empire all found new expression. Nahua communities encoded the suffering in codices and oral traditions, describing not only the death toll but the collapse of kinship structures, labor systems, and cosmological certainties.

The disease became part of a larger story, one in which colonial domination was affirmed not just through violence but through the inscrutable will of unseen forces. In this reading, cocoliztli becomes a symbolic fulcrum: it both explains suffering and validates submission. The logic of empire, once mapped by steel and catechism, was now enforced by epidemic.

Demographic Collapse and Colonial Reordering

Mortality estimates for the 1545 and 1576 outbreaks suggest population losses of up to 80 percent in some regions.5 These were not marginal declines. Entire villages disappeared from the tribute rolls, and labor drafts collapsed. The viceroyalty of New Spain, still in its bureaucratic adolescence, scrambled to recalibrate its economic expectations. The labor vacuum prompted legal reforms, including the expansion of African slavery and further reliance on encomienda structures.

Yet the devastation also served the imperial project. As historian Noble David Cook has emphasized, demographic collapse allowed Spain to reassert administrative control over territory previously governed by Indigenous elites.6 Epidemics thus acted as silent agents of empire, clearing the ground not only of bodies but of alternative sovereignties. This was not accidental. Spanish ecclesiastical and political narratives often interpreted the plagues as providential, evidence of divine favor for Christian rule and punishment for idolatry.

Here the line between natural disaster and ideological weapon blurs. Even as medical uncertainty prevailed, theological certainty reigned. The dead were mourned, but their deaths were narratively conscripted into the moral architecture of colonization.

Memory and Erasure: Cocoliztli in Historical Consciousness

Why, then, is cocoliztli not more prominent in historical imagination? Unlike the smallpox epidemic of 1520, which is tied to the siege of Tenochtitlan and the fall of the Aztec Empire, cocoliztli unfolded without a singular battle or moment of conquest. Its horror lay in its diffuse invisibility. It was everywhere and nowhere, touching highland valleys and mountain villages alike, leaving behind no ruins, only absence.

Modern Mexican historiography has slowly recovered cocoliztli’s narrative, but it remains peripheral. Schoolbooks and museum exhibits often foreground the more visually gripping stories of military conquest, religious imposition, and economic exploitation. The mass death of the mid-century plagues is harder to dramatize. It lacks clear heroes or villains.

Yet if we take seriously the scale and cultural impact of these epidemics, they demand inclusion in any serious account of colonial transformation. Cocoliztli did not just follow conquest; it completed it. Where the sword failed to break resistance, the fever succeeded. Where catechism struggled to win hearts, collapse won silence.

Conclusion: The Intimacy of Catastrophe

The cocoliztli epidemics remind us that empire is not only a story of power but of fragility. The Spanish did not simply impose their will upon a static world. They disrupted a delicate ecological and social order whose disintegration, in turn, enabled their dominance. The very engines of conquest (migration, forced labor, deforestation) produced the conditions for epidemic emergence.

Understanding cocoliztli, then, is not a matter of naming a microbe. It is a matter of confronting the layered violence of colonization: the violence of contact, of forgetting, of interpretation. The Nahua called it cocoliztli, a sickness. But it was also, perhaps, a reckoning.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Elinor Melville, A Plague of Sheep: Environmental Consequences of the Conquest of Mexico (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 73.

- Francisco Hernández, Rerum Medicarum Novae Hispaniae Thesaurus (Madrid: Juan de Madrigal, 1651), 202–205.

- Charles Gibson, The Aztecs under Spanish Rule: A History of the Indians of the Valley of Mexico, 1519–1810 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1964), 187.

- Åshild J. Vågene et al., “Salmonella enterica genomes from victims of a major 16th-century epidemic in Mexico,” Nature Ecology & Evolution 2 (2018): 520–528.Sherburne F. Cook and

- Woodrow Borah, Essays in Population History, Vol. 1: Mexico and the Caribbean (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971), 20–25.

- Noble David Cook, Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 151.

Bibliography

- Cook, Noble David. Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Cook, Sherburne F., and Woodrow Borah. Essays in Population History, Vol. 1: Mexico and the Caribbean. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971.

- Gibson, Charles. The Aztecs under Spanish Rule: A History of the Indians of the Valley of Mexico, 1519–1810. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1964.

- Hernández, Francisco. Rerum Medicarum Novae Hispaniae Thesaurus. Madrid: Juan de Madrigal, 1651.

- Melville, Elinor. A Plague of Sheep: Environmental Consequences of the Conquest of Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Vågene, Åshild J., et al. “Salmonella enterica genomes from victims of a major 16th-century epidemic in Mexico.” Nature Ecology & Evolution 2 (2018): 520–528.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.21.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.