It remains one of modernity’s unsolved puzzles, a sleep from which, perhaps, medical history itself has yet to fully awaken.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: A Pandemic Without a Memory

Between 1916 and 1930, an affliction known as Encephalitis Lethargica swept across the globe. Patients fell into trancelike states, their bodies inert while their minds teetered between consciousness and coma. Some never awoke. Others did, only to find themselves haunted by uncontrollable movements, distorted expressions, and bizarre compulsions that would later be recognized as post-encephalitic parkinsonism. The disease struck with chilling unpredictability, sparing no age group or nation, and then, as eerily as it appeared, it faded from view.

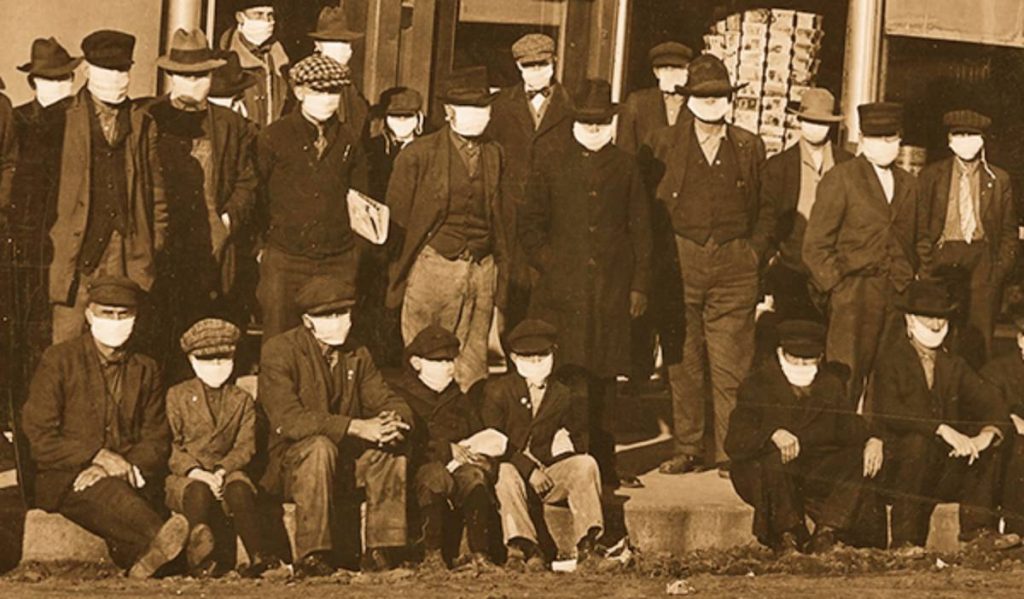

In an era already reeling from the devastation of the First World War and the concurrent influenza pandemic of 1918, Encephalitis Lethargica added a layer of mystery to an age marked by trauma. It unsettled both the public and the medical profession, defying diagnosis, resisting explanation, and, most troubling of all, refusing to fit neatly into the emerging frameworks of bacteriology and virology. The disease was not merely a neurological anomaly. It was a cultural event, an epistemological rupture, and a crisis of confidence for modern medicine.

The Emergence of the Epidemic: Disquiet in a Scientific Age

The first well-documented cases of Encephalitis Lethargica emerged in Vienna in the winter of 1916–1917, though retrospective accounts suggest earlier manifestations may have been misidentified.1 The syndrome quickly garnered attention due to its perplexing clinical profile: a combination of high fever, profound sleepiness or akinetic mutism, ocular paralysis, and, in some cases, psychiatric disturbances.

By 1919, clusters of cases were reported throughout Europe and North America. The medical establishment initially hesitated to call it an epidemic. Doing so would imply not only contagion but the potential for widespread societal disruption. Yet the numbers grew too large to ignore. Thousands of cases were reported annually, and mortality rates varied widely. Some died within days. Others lived for years, slowly degenerating under the weight of motor dysfunction and cognitive decline.2

The most unsettling cases were the survivors. Though they emerged from the acute phase, they were changed. They walked stiffly, with masklike faces and tremors. Others displayed explosive laughter, compulsive tics, or periods of catatonia. The physician Constantin von Economo, who would become the disease’s reluctant authority, identified three clinical forms—somnolent-ophthalmoplegic, hyperkinetic, and amyostatic-akinetic—and yet acknowledged the boundaries were porous.3

Medicine had grown confident in the early twentieth century. Germ theory had revolutionized diagnosis, and new diagnostic tools like spinal taps and staining techniques promised clarity. But Encephalitis Lethargica confounded all categories. Its etiology remained unknown. No consistent pathogen could be identified. No single treatment proved effective. It became a pathology of ambiguity.

Contextual Shadows: War, Influenza, and Uncertainty

To understand the full cultural weight of Encephalitis Lethargica, one must situate it within its broader historical context. The Great War had already upended notions of progress and civilization. The 1918 influenza pandemic followed, killing millions in a matter of months. Against this backdrop, the emergence of a new and baffling disease felt like a further unraveling.

The temporal proximity of Encephalitis Lethargica to the influenza pandemic led many to suspect a connection. Some theorized that the influenza virus had triggered an autoimmune reaction or latent neuroinflammation. Yet despite considerable investigation, no direct causal link was ever established.4

What did emerge, however, was a sense of unease. This was no medieval plague. It did not spread in predictable waves or burn itself out quickly. It lingered. It produced chronic disability. It affected the brain—the seat of personality, of thought, of will. It exposed the limits of the laboratory gaze and, in doing so, haunted the confidence of a newly professionalized medical elite.

Clinical Encounters and Cultural Anxiety

The clinical literature of the 1920s and 1930s on Encephalitis Lethargica is marked by two tones: meticulous documentation and underlying desperation. Physicians wrote with unusual narrative flourish, detailing the psychological states of their patients, the strangeness of their movements, the eeriness of their stares. Neurologists such as Arthur J. Hall in Sheffield and Karl Stern in Berlin provided haunting case studies in which patients would sit unmoving for hours, respond to commands after prolonged delay, or act out compulsive behaviors with robotic consistency.5

This was not a disease easily abstracted into statistics. It demanded attention to the idiosyncrasies of personhood. Its victims were often described as spectral, suspended between sleep and waking, agency and paralysis. The medical encounter itself became uncanny.

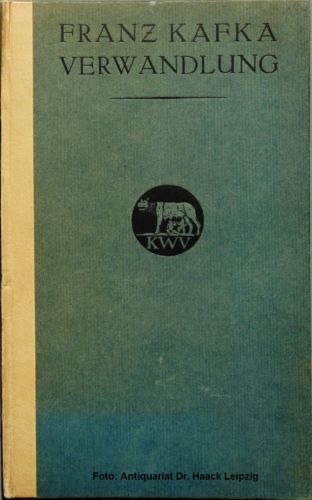

These experiences resonated beyond the clinic. Cultural representations of the time, ranging from Kafka’s The Metamorphosis to German Expressionist film, reflected a similar fascination with deformed movement, mechanized bodies, and loss of self. The figure of the encephalitic patient became, implicitly, a metaphor for broader social disorientation. The war had produced the shell-shocked. The interwar years, in turn, produced the sleepwalker.

Post-Encephalitic Parkinsonism: Living After the Plague

For many patients, the acute infection was not the end but the beginning of a long decline. In the years following the epidemic’s peak, thousands developed what came to be known as post-encephalitic parkinsonism. They exhibited rigidity, bradykinesia, tremors, and speech difficulties. But unlike classic Parkinson’s disease, these patients were often younger and their symptoms more abrupt in onset.

The condition proved tragically resistant to treatment. Bed rest, hydrotherapy, and sedatives were used with little effect. Surgical interventions, including experimental procedures on the basal ganglia, yielded mixed results. In time, many of these patients were institutionalized, becoming part of what the historian Joel Braslow has called the “forgotten population” of twentieth-century medicine.6

The philosopher-historian Georges Canguilhem would later write that medicine, when confronted with the unknown, reveals not only its knowledge but its limits. Encephalitis Lethargica exposed those limits in brutal fashion. It left behind a generation of damaged bodies and unanswerable questions.

Echoes in the Late Twentieth Century: The Awakenings

For decades, Encephalitis Lethargica remained a historical curiosity. Then, in the 1960s, neurologist Oliver Sacks encountered a group of post-encephalitic patients at Mount Carmel Hospital in the Bronx. They had survived the epidemic as children or adolescents and lived in a state of profound neurological dormancy. Sacks administered the then-experimental drug L-DOPA, which temporarily restored movement and speech in these patients, though the results were bittersweet and often transient.7

Sacks’s account, published in Awakenings (1973), reintroduced the world to the epidemic and its human toll. Through literary narrative rather than clinical abstraction, he revealed the inner lives of patients who had long been reduced to silence. Yet even Sacks’s work could not solve the deeper mystery of what Encephalitis Lethargica had been or why it had vanished.

The disease remains without a confirmed cause. Some suspect it was viral, others autoimmune. A few speculate it may have been several diseases misclassified under one name. In 2004, neurologist Russell Dale proposed a model involving basal ganglia autoimmunity, but no definitive consensus has emerged.8

Conclusion: The Silence That Followed

Encephalitis Lethargica is often called the forgotten epidemic, but forgetting implies neglect. In truth, it was remembered, though imperfectly, as a trauma too strange for easy integration. It defied the narrative of medical triumph that so often accompanies the twentieth century.

More than a clinical entity, it became a historical riddle. It challenged the certainty of diagnostic science, exposed the fragility of medical authority, and raised enduring questions about memory, personality, and care. The real story of Encephalitis Lethargica is not only about the disease but about the response to it.

It remains one of modernity’s unsolved puzzles, a sleep from which, perhaps, medical history itself has yet to fully awaken.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Joel Vilensky, “Encephalitis lethargica: During and After the Epidemic,” Archives of Neurology 57, no. 10 (2000): 1421–1427.

- Howard H. Tooth, “A Clinical Lecture on Epidemic Encephalitis,” British Medical Journal 2, no. 3221 (1920): 541–545.

- Constantin von Economo, Encephalitis Lethargica: Its Sequelae and Treatment (London: Oxford University Press, 1931), 14–26.

- Anne Hudson, “Was the 1918 Influenza Responsible for Encephalitis Lethargica?” Journal of Medical Biography 17, no. 3 (2009): 170–174.

- Arthur J. Hall, “Studies in Epidemic Encephalitis,” Brain 43, no. 4 (1920): 445–481.

- Joel T. Braslow, Mental Ills and Bodily Cures: Psychiatric Treatment in the First Half of the Twentieth Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 118–124.

- Oliver Sacks, Awakenings (New York: Dutton, 1973).

- Russell C. Dale et al., “Autoantibodies to Basal Ganglia in Sydenham’s Chorea and Related Disorders,” Pediatrics 113, no. 4 (2004): 578–582.

Bibliography

- Braslow, Joel T. Mental Ills and Bodily Cures: Psychiatric Treatment in the First Half of the Twentieth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

- Dale, Russell C., et al. “Autoantibodies to Basal Ganglia in Sydenham’s Chorea and Related Disorders.” Pediatrics 113, no. 4 (2004): 578–582.

- Economo, Constantin von. Encephalitis Lethargica: Its Sequelae and Treatment. London: Oxford University Press, 1931.

- Hall, Arthur J. “Studies in Epidemic Encephalitis.” Brain 43, no. 4 (1920): 445–481.

- Hudson, Anne. “Was the 1918 Influenza Responsible for Encephalitis Lethargica?” Journal of Medical Biography 17, no. 3 (2009): 170–174.

- Sacks, Oliver. Awakenings. New York: Dutton, 1973.

- Tooth, Howard H. “A Clinical Lecture on Epidemic Encephalitis.” British Medical Journal 2, no. 3221 (1920): 541–545.

- Vilensky, Joel. “Encephalitis lethargica: During and After the Epidemic.” Archives of Neurology 57, no. 10 (2000): 1421–1427.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.21.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.