This termination reveals the fragility of institutions that once seemed stable. It exposes the ease with which history can be turned into terrain.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

A Break with Precedent

In the quiet halls of the National Archives and Records Administration, history usually rests more than it resists. Archivists work behind the scenes, not at the podium. Their job is to preserve, not provoke. But when Donald Trump abruptly fired the sitting National Archivist, Dr. Colleen Shogan, that quiet work became the epicenter of a deepening constitutional drama.

The dismissal, though technically within a president’s authority, shattered a long-standing norm. No previous president had ever removed a National Archivist outright. While archivists serve at the pleasure of the president, the position has historically been understood as insulated from direct political interference. Until now, the role had never been so bluntly politicized.

Trump’s move follows years of intensifying conflict over presidential records, declassification practices, and the handling of sensitive documents. It comes amid a second Trump term already marked by aggressive challenges to institutional boundaries and a continued refusal to cede ground in the battle over narrative, legitimacy, and control.

The Records at the Center of the Storm

The National Archives, though bureaucratic in function, plays a quietly vital role in the American republic. It is the final custodian of presidential records, a repository for the historical memory of each administration, and the chief guardian of the Presidential Records Act, a law passed in the wake of Watergate to ensure that official records belong to the public, not to presidents themselves.

Under this law, archivists are responsible for securing records at the end of a presidential term, coordinating with outgoing administrations to preserve documents, emails, communications, and more. These materials are then cataloged, stored, and eventually made available to the public, subject to various timelines and security classifications.

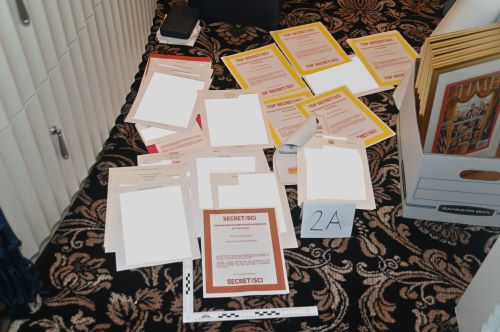

Tensions between Trump and the Archives first erupted in early 2022, when classified documents were discovered at Mar-a-Lago. That episode led to a cascade of investigations, criminal charges, and public debate about secrecy, accountability, and presidential privilege. The Archives, largely viewed as a neutral authority, became a lightning rod. Trump and his allies began casting the institution as part of a broader “deep state” conspiracy.

Now, with a second term secured and fewer checks on his authority, Trump has wielded his dictatorial Sharpie. The firing of the Archivist signals a clear shift. Control over the past – who shapes it, who tells it, and who is allowed to see it – is now firmly part of the new political battlefield.

Power, Narrative, and the Stakes of Memory

History, it turns out, is not only written by the victors. It is also redacted, filed, and occasionally disappeared. In firing the Archivist, Trump has opened the door to questions that go far beyond paperwork. What counts as a presidential record? Who decides what the public gets to know? And can the nation trust its own government to remember honestly?

This is not merely a bureaucratic scuffle. In recent months, conservative lawmakers have introduced legislation to revise the Presidential Records Act, arguing that presidents should have more discretion over which materials are retained and which are kept private. Others want to shorten the embargo periods on access to executive documents, effectively accelerating the timeline for political influence.

Critics see these moves as an effort to rewrite the rules in real time, to control the future’s access to the present by narrowing the lens through which history is later viewed. A politicized archives, they argue, becomes less a mirror and more a megaphone.

For historians, librarians, journalists, and civic watchdogs, the firing represents a dangerous precedent. The idea that a sitting president can remove the nation’s chief archivist during an ongoing dispute over records raises alarms not just about transparency, but about the erosion of democratic memory itself.

The Archivist’s Role and the Limits of Resistance

The role of the National Archivist is inherently paradoxical. It requires both neutrality and vigilance, humility and courage. While archivists do not make laws, they enforce them. They do not craft policy, but they safeguard the paper trail that reveals how policy was made.

The outgoing Archivist, known for her low public profile and steady administration, had pushed back on attempts to limit access to Trump-era documents. She defended the Archives’ coordination with the Justice Department and stood by the institution’s legal mandate, even amid political attacks.

By removing her, Trump has sent a message: institutions that resist can be reshaped.

There is precedent for politicized memory elsewhere in the world. In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has restructured museums and historical archives to reinforce nationalist narratives. In Russia, Putin’s regime has cracked down on archives that challenge official versions of history. The United States, until now, had been buffered by professional norms and civic trust. Those buffers are fraying.

A National Reckoning with Its Own Paper Trail

The implications of this firing will not be fully known for years. But it is likely that the next Archivist will face pressure not only to manage documents, but to manage perception.

Already, legal scholars are debating whether the dismissal violates the spirit, if not the letter, of post-Watergate reforms. Congressional committees are calling for hearings. Advocacy groups are demanding that the appointment of a new Archivist be subject to additional transparency.

And in the background, a quieter battle continues. Every administration produces thousands of pages of documents each day. Some will be preserved. Others will vanish. The future record is being built, one decision at a time.

What It Means to Forget

There is a cost to erasing parts of the national record, even if that cost is not immediately visible. Over time, democratic societies depend on archives to hold institutions accountable, to teach future generations, and to trace the evolution of power.

Without access to a clear and complete record, the past becomes a tool rather than a guide. Memory turns from mirror to mask.

The firing of the National Archivist is not, on its face, a constitutional crisis. But it is a cultural one. It reveals the fragility of institutions that once seemed stable. It exposes the ease with which history can be turned into terrain. And it asks us to confront a hard question: What kind of country do we become when we no longer agree on how, or whether, to remember ourselves?

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.22.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.