When a virus as familiar as influenza can trigger brain damage in otherwise healthy children, the line between routine and catastrophic becomes difficult to draw.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

A Rare Diagnosis with Devastating Consequences

When a child catches the flu, most parents brace for fevers, fatigue, and days of careful monitoring. Few anticipate brain damage. Fewer still have ever heard of acute necrotizing encephalopathy, or ANE, a rare and often catastrophic neurological complication that can follow common viral infections such as influenza.

But among pediatric neurologists, awareness of ANE is growing with a renewed sense of urgency. Once considered an extremely rare post-viral syndrome, ANE is now appearing in medical literature with increasing frequency. Several major children’s hospitals in the United States, Japan, and Europe have reported a rise in suspected or confirmed cases over the past three flu seasons.

In a world where global viral transmission moves faster than ever before, and where pediatric immune systems are increasingly exposed to variant strains of influenza, ANE is no longer an outlier. It is becoming a frightening emblem of how flu, still perceived by many as routine, can spiral into profound medical crisis.

What Is Acute Necrotizing Encephalopathy?

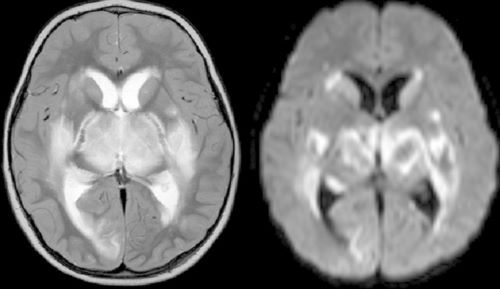

ANE is characterized by rapid inflammation and swelling in parts of the brain, particularly the thalami, brainstem, and cerebellum. These regions control core bodily functions, emotional processing, and coordination. The disease typically follows viral infections, especially influenza A, but has also been linked to SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses.

The precise mechanism behind ANE remains incompletely understood. It is not caused by the virus invading the brain directly, as in encephalitis. Instead, it appears to result from a hyperinflammatory immune response, a cytokine storm that causes blood-brain barrier breakdown, hemorrhage, and necrosis in brain tissue.

Children with ANE often present with flu-like symptoms, then rapidly deteriorate within 24 to 48 hours. Seizures, coma, and multi-organ failure can follow. Mortality rates remain high, and survivors are frequently left with severe neurological disabilities, including speech loss, motor impairment, or cognitive regression.

There is no cure. Treatment is focused on early recognition, aggressive management of inflammation with corticosteroids or intravenous immunoglobulin, and intensive supportive care.

Rising Incidence and Global Red Flags

While still rare in absolute terms, the increase in reported ANE cases is not going unnoticed. Japan, where the condition was first described in the 1990s, has tracked rising pediatric incidence alongside severe flu seasons. A 2022 study published in The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific noted an uptick in cases correlated with earlier and more virulent flu strain circulation.

In the United States, Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., documented 58 cases, 41 of which met the criteria, of ANE during the 2024-2025 winter season alone, more than in the prior five years combined. Similar reports have come from institutions in Boston, Chicago, and Houston.

In the United Kingdom, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health issued a clinical advisory in early 2024 warning of increased neurological complications associated with influenza, including a marked rise in inflammatory encephalopathies resembling ANE.

Some researchers believe the trend may be partly due to better recognition and improved neuroimaging. But many believe the increase is real, not just statistical. The strain on pediatric ICU beds during seasonal surges, coupled with longer durations of viral circulation and reduced population immunity in children following pandemic-era isolation, may be feeding the rise.

Stories Behind the Statistics

ANE is rare enough that few parents have heard of it, until it strikes. The families it affects are often blindsided. Their stories are heartbreaking and sobering.

In one case in 2023, a previously healthy two-year-old girl started spiking a fever. She was not current on her vaccination, though not because her parents were vaccine resistors, she simply had not yet had her scheduled wellness check. The girl did not survive.

Despite aggressive intervention, the child now requires ongoing physical therapy and has lost most of her expressive language skills. Her family has joined a small but growing network of ANE parents who advocate for better flu vaccination rates and earlier recognition of neurological red flags in children with viral infections.

Underdiagnosed, Underresearched

One of the most troubling aspects of ANE is how little is known. Fewer than 600 cases have been documented worldwide in peer-reviewed literature. Experts believe the actual number is likely far higher, particularly in regions where neuroimaging is less accessible or where post-viral neurological deterioration is misattributed to other causes.

There is also evidence that genetic predispositions may play a role. Mutations in the RANBP2 gene have been associated with recurrent familial cases of ANE, particularly in East Asian populations. But many children with ANE do not carry this mutation, and the reasons why some children experience catastrophic inflammation while others recover uneventfully from the flu remain elusive.

Funding for research into ANE is minimal. It sits at the intersection of rare disease, infectious disease, and neurology, none of which receive significant attention when the case counts remain low and public awareness is sparse.

Prevention and the Limits of Control

The best known defense against ANE remains the seasonal influenza vaccine. While no vaccine can completely eliminate risk, studies consistently show that flu vaccination reduces the likelihood of severe complications.

Yet vaccination rates among children remain suboptimal in many regions. In the United States, coverage rates for the 2024–2025 flu season fell below 50 percent in several states, despite public health campaigns. Vaccine hesitancy, fatigue from pandemic messaging, and logistical barriers continue to impede uptake.

Parents are encouraged to watch for signs of neurological distress (extreme sleepiness, confusion, persistent vomiting, seizures) in children recovering from viral illnesses. Physicians are advised to consider neuroimaging early when symptoms are suspicious. But prevention remains far preferable to treatment, especially when the window for intervention is so narrow.

A Warning Wrapped in a Whisper

Acute necrotizing encephalopathy does not capture headlines like RSV surges or COVID variants. It does not spread from child to child in classrooms or require mass quarantines. It emerges suddenly, silently, and with devastating speed.

Its rarity should not lull policymakers into complacency. Rising cases suggest that changing viral dynamics, global travel, and pediatric immune vulnerability are converging in dangerous ways. The same pathogens that once posed moderate risks may now carry consequences more severe than previously understood.

In many ways, ANE forces a reconsideration of what “mild” infections really mean. When a virus as familiar as influenza can trigger brain damage in otherwise healthy children, the line between routine and catastrophic becomes difficult to draw. It may be a whisper now. But it speaks volumes about where public health is heading if we fail to listen.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.06.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.