To study its architecture is not merely to catalog renovations or stylistic shifts. It is to trace the shifting contours of American identity, power, and memory.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Foundations of a Republic and a Residence

The White House is not merely a structure; it is a symbol made stone, a spatial embodiment of a nation’s evolving conception of authority, elegance, and restraint. Though its silhouette is instantly recognizable, the meanings encoded within its neoclassical columns, its carefully chosen site, and its subsequent renovations reveal a history layered with ambition, contradiction, and reinvention. This essay traces the architectural history of the White House from its conception in the crucible of the early Republic to its status as a modern emblem of American executive power, revealing a building shaped as much by myth and memory as by marble and mortar.

Unlike the ornate palaces of Europe’s monarchs, the American president’s home was envisioned in the shadow of republican virtue. Yet paradoxically, it would draw on classical ideals that had once adorned the autocratic courts of emperors. This tension between simplicity and splendor, between power and public accessibility, would haunt every phase of the White House’s construction, renovation, and symbolic life.

The Federal Vision: Designing an Architecture for Democracy

L’Enfant’s Plan and the Search for Gravitas

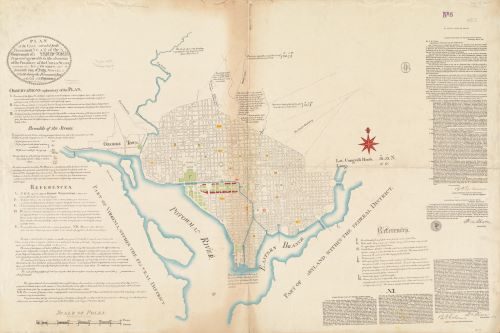

The story of the White House begins within a broader design, Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s ambitious plan for the new capital city. Commissioned by George Washington in 1791, L’Enfant’s vision was imperial in scale but republican in rhetoric. He envisioned long sightlines, broad avenues, and monumental buildings that would rival Rome and Paris in grandeur while embodying the civic virtue of a republic. At the heart of this vision was the “President’s House,” which L’Enfant placed on a ridge with a commanding view of the Potomac River, anchoring the executive within both the landscape and the metaphorical terrain of power.1

L’Enfant’s high-handed methods alienated key allies, and he was eventually dismissed. Yet the conceptual blueprint remained, including the prominent site for the presidential mansion. The very act of choosing that site, on elevated terrain, visible yet set apart, was itself a statement about executive dignity.

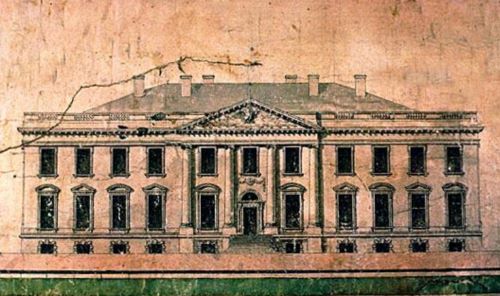

Hoban’s Neoclassicism and Washington’s Oversight

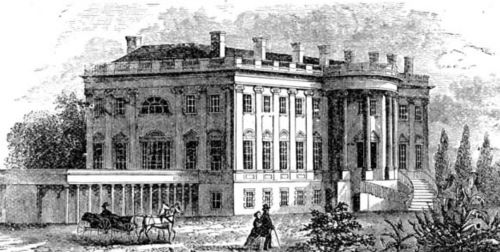

To design the President’s House, a public competition was held. Though Thomas Jefferson anonymously submitted a design, it was the Irish-born architect James Hoban whose neoclassical proposal won favor. Hoban’s plan bore the imprint of Georgian sensibilities, with symmetrical proportions and a Palladian influence that drew on contemporary European ideals of refinement.2

George Washington played an active, if often overlooked, role in shaping the White House. Though he never lived in it, his vision guided its scale and symbolism. He insisted the house be large enough to command respect abroad and signify stability at home. Washington’s alterations to Hoban’s original plans, most notably enlarging the structure, suggest a pragmatic understanding of architecture’s performative power.3 The house was to be more than a dwelling; it was to be a stage upon which the presidency would be enacted.

Fire and Rebirth: The War of 1812 and a New Identity

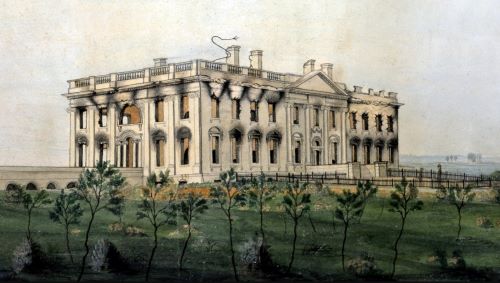

The British Torch the Symbol

In 1814, British troops burned the White House during the War of 1812, an act that struck not just at a building but at the image of the nation itself. The smoldering ruins exposed the vulnerability of American institutions, both militarily and architecturally. The building’s destruction, its stone walls left blackened, would ultimately reinforce its symbolic weight, as ruins often do. The decision to rebuild rather than redesign the White House was itself an assertion of continuity and resilience.4

The restoration, again under Hoban’s direction, remained largely faithful to the original design. But the moment had changed. The building was no longer simply the home of the president; it had become a site of national memory. The fire, paradoxically, conferred sanctity.

Monroe, Latrobe, and the Federal Aesthetic

With James Monroe’s administration came new furnishings, new wings, and renewed emphasis on elegance. Architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, whose previous work included the U.S. Capitol, introduced subtle modifications rooted in American materials and motifs.5 These included native woods and iconography designed to reflect the country’s emerging identity apart from British aesthetic dominance.

Under Latrobe, the White House moved closer to what might be called a Federal style, still neoclassical, yet imbued with local meaning. The house became not only a symbol of power but also of craftsmanship and innovation. It married European lineage with New World particularity.

Expanding Power: The Nineteenth Century and Westward Ambitions

Victorian Layers and Manifest Destiny

As the nation expanded westward and sectional tensions grew, so too did the presidency, and the White House attempted to keep pace. The 1850s saw the addition of the north and south porticos, which gave the house a more monumental façade, enhancing its sense of formality and permanence.6 These additions reflected the ambitions of a nation that now saw itself as continental.

Yet the building often lagged behind the institutional realities it was meant to symbolize. Andrew Jackson, for instance, presided over an increasingly powerful executive from a house still designed for a modest, eighteenth-century presidency.7 The architecture strained against the office’s expanding authority.

The Civil War and Symbolic Function

During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln used the White House as a command center, a public meeting ground, and a private sanctuary. The building’s symbolic resonance deepened as it became the site of emancipatory proclamations and wartime deliberation. Its public rooms, worn and shabby by then, reflected the moral exhaustion of the era, but also its solemnity. Visitors often remarked on the austere dignity of the space.8

In this period, the White House emerged less as a stylistic marvel than a national altar. It absorbed and projected the gravity of the moment.

The Modern Presidency and Architectural Adaptation

The Roosevelt Renovations and the Executive Office

By the early twentieth century, the demands of the modern presidency had thoroughly outstripped the capacity of Hoban’s structure. Theodore Roosevelt, seeking a more functional and expansive workspace, oversaw the creation of the West Wing in 1902, relocating the president’s offices from the residence proper.9 Designed by Charles Follen McKim, the West Wing marked a decisive shift: the architectural separation of private life from public duty.

This separation of functions symbolized the bureaucratization of the presidency. The White House was no longer merely a home for the president; it was now a multi-functional political organism. Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, and subsequent occupants would further entrench this transformation, adapting the complex to suit the demands of governance in an industrial, global age.

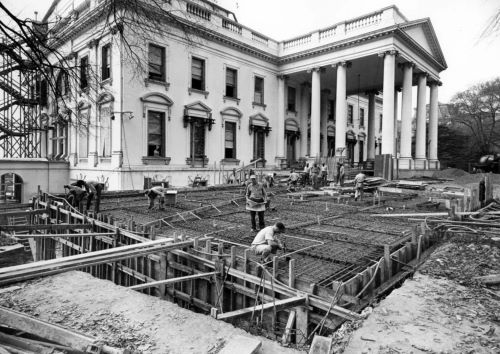

Truman’s Gutting and the Paradox of Preservation

By the 1940s, structural decay forced a dramatic intervention. Between 1948 and 1952, under Harry Truman, the interior of the White House was entirely gutted and rebuilt using steel-reinforced concrete. Only the original outer walls remained.10 Though the reconstruction preserved the appearance of the White House, it severed the building’s physical continuity with the past. Critics decried the result as a “shell” or “facade.”

Yet even this rupture reflects a deeper truth: that historical meaning often depends less on material continuity than on ritual, memory, and myth. Truman himself, aware of the symbolism at stake, preserved architectural fragments and emphasized fidelity to the original design.11 The rebuilt White House, like the nation itself, emerged from the upheaval both altered and affirmed.

Conclusion: The White House as Palimpsest

The White House today is at once timeless and in flux. Its design, born of neoclassical aspiration and republican restraint, has absorbed the energies of empire, civil war, modernization, and spectacle. It is a palimpsest: a surface continually rewritten, yet never fully erased.

To study its architecture is not merely to catalog renovations or stylistic shifts. It is to trace the shifting contours of American identity, power, and memory. From Hoban’s Georgian lines to Truman’s steel beams, the White House mirrors the contradictions of the country it houses, a republic founded in hierarchy, a republic haunted by its imperial temptations, a nation always becoming.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Scott Berg, Grand Avenues: The Story of the French Visionary Who Designed Washington, D.C. (New York: Pantheon, 2007), 103–104.

- William Seale, The President’s House: A History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), 1:72–74.

- Ibid., 1:79–81.

- Anthony S. Pitch, The Burning of Washington: The British Invasion of 1814 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1998), 185–192.

- Dell Upton, Architecture in the United States (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 90–92.

- Seale, The President’s House, 2:355.

- Richard Ellis, The Development of the American Presidency (New York: Routledge, 2012), 136–138.

- Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 388–392.

- Patrick Phillips-Schrock, The Nixon White House Redecoration and Acquisition Program: An Illustrated History (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2016), 10–12.

- Seale, The President’s House, 2:520–529.

- Elizabeth Brown Pryor, Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters (New York: Viking, 2007), 211–212.

Bibliography

- Berg, Scott. Grand Avenues: The Story of the French Visionary Who Designed Washington, D.C. New York: Pantheon, 2007.

- Ellis, Richard. The Development of the American Presidency. New York: Routledge, 2012.

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006.

- Phillips-Schrock, Patrick. The Nixon White House Redecoration and Acquisition Program: An Illustrated History. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2016.

- Pitch, Anthony S. The Burning of Washington: The British Invasion of 1814. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1998.

- Pryor, Elizabeth Brown. Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters. New York: Viking, 2007.

- Seale, William. The President’s House: A History. 2 vols. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986.

- Upton, Dell. Architecture in the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.05.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.