The history of ancient weather prediction is not a linear march toward scientific truth. It is a tapestry woven from empirical insight, cultural symbolism, and the imperatives of survival.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Weather as an Ancient Human Preoccupation

Long before satellites traced cloud bands across the Earth’s surface, human communities sought to understand and predict the shifting patterns of the sky. Weather was never simply a matter of passing curiosity. For agrarian societies, it determined the timing of planting and harvest; for maritime cultures, it dictated the very possibility of safe travel; and for rulers, it could decide the outcome of campaigns or the survival of a people through winter. The earliest known efforts at weather forecasting reveal a world in which observation, cosmology, and ritual converged. These were not scientific in the modern sense, but they represented coherent systems of thought that linked the visible heavens with the needs of life on the ground.1

Babylonian Sky-Watching and the Logic of Omens

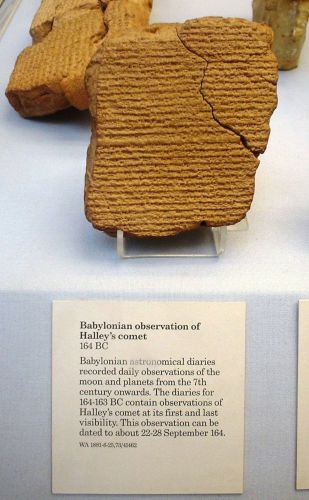

The Babylonians, active in Mesopotamia by the mid-first millennium BCE, developed some of the earliest recorded methods of anticipating short-term weather changes.2 Their approach was rooted in a complex interplay of empirical observation and divination. Clay tablets from around 650 BCE describe how the appearance of clouds, the coloration of the sky, and the presence of optical phenomena such as haloes could be read as signs of impending rain, wind, or drought.3

To modern eyes, the reliance on haloes around the Sun or Moon as indicators of storms might seem naïve. Yet such signs have a genuine meteorological basis: high cirrostratus clouds, which can produce halo effects, often precede frontal systems. The Babylonians did not isolate cause and effect in the manner of contemporary science, but their long record of observation gave them a measure of predictive power. More significantly, weather was not merely a physical process; it was a form of divine communication. The same clouds that suggested rain might also be interpreted as signs of favor or disfavor from the gods, particularly for rulers whose legitimacy depended on celestial approval.

The Chinese Calendar of Weather

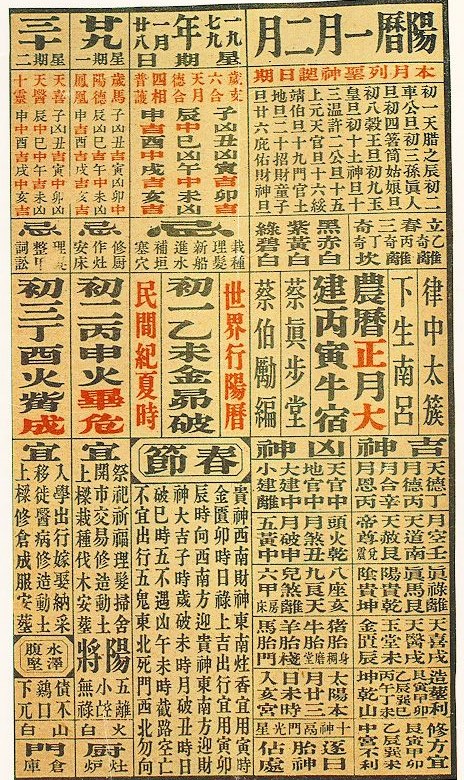

By 300 BCE, Chinese astronomers and scholars had integrated weather prediction into a larger cosmological and calendrical system.4 Their annual calendar was divided into twenty-four solar terms, each associated with characteristic weather patterns, seasonal agricultural tasks, and ritual observances. This structure reflected both accumulated empirical knowledge and the Confucian ideal of harmonizing human activity with the rhythms of nature.

The accuracy of these divisions was sufficient to guide generations of farmers, though the explanations for their regularity were rooted in the interplay of Yin and Yang and the cycles of the Five Phases, rather than in atmospheric physics. For the Chinese court, mastery of seasonal knowledge was not only practical but political: a ruler who could align policy and ceremony with the heavens reinforced the perception that he governed in accordance with cosmic order.

Aristotle and the Classical Tradition

The Greek philosopher Aristotle offered perhaps the most influential synthesis of ancient meteorological thought. Around 340 BCE, he composed the four-volume Meteorologica, a work that addressed the formation of rain, clouds, hail, winds, thunder, lightning, and hurricanes, alongside topics in astronomy, geography, and natural philosophy.5 His treatise combined careful observation with speculative reasoning, presenting a vision of weather as part of a natural order governed by the four elements: earth, air, fire, and water.

Aristotle’s observations were sometimes strikingly perceptive. He noted, for example, that winds could be driven by temperature differences and that certain clouds were precursors to storms. Yet he also advanced ideas that later proved erroneous, such as the belief that winds originated from subterranean exhalations. Despite these flaws, his framework dominated European and Islamic meteorological thinking for nearly two millennia. Not until the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century did scholars systematically dismantle and replace his theories with empirical models.

Cultural Contexts and the Boundaries of Knowledge

Ancient weather forecasting cannot be disentangled from the cultural and intellectual environments in which it developed. In Mesopotamia, weather was part of a divinatory matrix; in China, it was a manifestation of cosmic harmony; in the Hellenic world, it was an arena for philosophical speculation about nature’s causes. None of these traditions sought weather knowledge as an isolated science. Instead, each embedded it within broader systems of meaning, authority, and legitimacy.

It is worth noting that these early forecasting traditions often endured precisely because they were insulated from falsification. When prediction failed, it was not necessarily the method that was blamed but the interpretation or the will of the gods. The absence of a rigid empirical standard allowed these systems to persist, carrying both accurate observations and mistaken explanations forward for centuries.

Conclusion: The Long Echo of Early Forecasting

The history of ancient weather prediction is not a linear march toward scientific truth. It is a tapestry woven from empirical insight, cultural symbolism, and the imperatives of survival. The Babylonians, the Chinese, and Aristotle’s successors each advanced the human capacity to anticipate the future of the skies, even as they worked within intellectual frameworks that limited their reach.

In reflecting on these traditions, we see the enduring human impulse to read meaning into the clouds, to see the turn of the wind not only as a natural event but as a sign. Modern meteorology, with its satellites and supercomputers, is heir to this impulse, though it replaces divine omens with data models. The difference is profound, yet the underlying desire is the same: to bring the uncertainty of the heavens into the realm of human understanding.

Appendix

Footnotes

- George Sarton, Ancient Science through the Golden Age of Greece (New York: Dover Publications, 2012), 42–44.

- Francesca Rochberg, The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 215.

- John M. Steele and J.M.K. Gray, “A Study of Babylonian Observations Involving the Zodiac,” Journal for the History of Astronomy, Vol. 38, Part 4, No. 133 (November 2007): 443-458.

- Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1954), 395–99.

- Aristotle, Meteorologica, trans. H. D. P. Lee (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1952).

Bibliography

- Aristotle. Meteorologica. Translated by H. D. P. Lee. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1952.

- Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1954.

- Rochberg, Francesca. The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Sarton, George. Ancient Science through the Golden Age of Greece. New York: Dover Publications, 2012.

- Steele, John M and J.M.K. Gray. ” A Study of Babylonian Observations Involving the Zodiac.” Journal for the History of Astronomy Vol. 38, Part 4, No. 133 (November 2007): 443-458.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.11.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.