The barber-surgeon was at once despised and sought after, a liminal figure who embodied the blurred boundaries of medieval medicine.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Ambiguous Healer

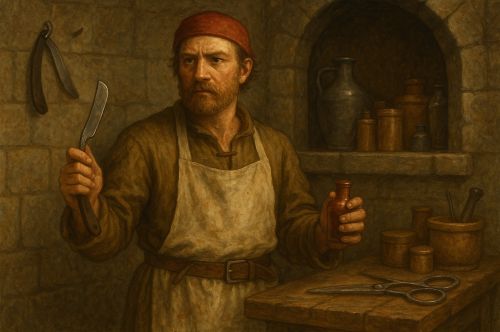

The barber-surgeon of medieval Europe belonged to no single world. He was neither the lofty physician, immersed in Galen and Avicenna, nor the mere craftsman shaving heads in a marketplace stall. He stood between them. A figure of paradox, he was mocked as a butcher yet courted as a healer. Communities turned to him precisely because he was present in the lanes and squares, ready with his razors and lancets when illness or accident struck.1

This ambiguity was essential. Physicians often remained distant, bound to the wealthy and the university. The barber-surgeon was immediate. He was the man who could pull a tooth on the spot, lance a boil without ceremony, or shave a head in preparation for surgery. His very accessibility shaped his reputation, at once lowly and indispensable.

Bloodletting and the Humors

If any practice defined the barber-surgeon, it was bloodletting. Grounded in the ancient theory of the four humors, bleeding was supposed to release excess blood and restore balance.2 The act was both ritual and cure, its familiarity reinforcing its credibility. Physicians ordered it, but barbers performed it, nicking a vein with a practiced stroke and watching as the crimson arc filled a waiting bowl.

The barber’s pole, red and white, still carries this memory. The red band marked blood, the white was for bandages, and the pole itself symbolized the staff patients gripped while the procedure was carried out.3 To modern eyes, this seems brutal. To the medieval patient, it was routine, even reassuring.

Yet bloodletting was not only therapeutic; it was seasonal. Medieval calendars recommended bleeding at specific times of the year, aligning medicine with astrology and the cycles of the moon. In this way, the barber-surgeon was not just a craftsman but a participant in the cosmic order, his cuts synchronizing the body with the heavens.

Surgery as Craft

Surgery sat uneasily in the hierarchy of medicine. Learned physicians disdained it, dismissing cutting and stitching as manual work beneath their dignity. Yet broken bones, sword wounds, and ulcerated flesh demanded hands, not theory. It was here the barber-surgeon made his claim. He stitched, amputated, and set fractures with the same tools he used to groom.

Some men gained renown, particularly in cities where violence furnished steady work. Others remained humble village practitioners. In either case, surgery for them was not science but craft, a skill learned by apprenticeship rather than by the book. This closeness to the body gave them a form of authority physicians often lacked.4

The Social Perception of the Barber-Surgeon

Communities viewed barber-surgeons with suspicion as much as respect. They were useful, but their intimacy with blood and pus seemed polluting. Medieval society placed a premium on intellectual distance; the hand that cut and stitched was considered less noble than the mind that prescribed. Physicians and poets alike mocked barbers as rough tradesmen who meddled in medicine.5

And yet, patients came. The disdain of elites mattered little to someone with a festering wound. For those who could not afford or even reach a physician, the barber-surgeon was healer of necessity. The contradiction was never resolved: he remained both despised and essential, his reputation forever divided.

In popular culture, this duality found expression in jokes, proverbs, and plays. The barber was a figure of ridicule, often portrayed as bungling or greedy. But satire itself testifies to his prominence; one does not mock what is insignificant. He was part of the social fabric, recognized in every town and village.

Guilds, Regulation, and Rivalries

By the thirteenth century, barber-surgeons began to organize. Guilds emerged in London, Paris, and the German towns, formalizing training and protecting members from rivals. Apprenticeships were set, rules codified, and standards enforced. What had begun as a loose craft hardened into an institution.

The rivalry with physicians sharpened in the same centuries. Physicians wielded authority of theory and Latin texts; barbers held authority of touch. In England, Henry VIII’s 1540 charter merged the London barbers with the Fellowship of Surgeons, producing the Company of Barber-Surgeons.6 The union did not erase tensions, but it acknowledged that the barber-surgeon could no longer be dismissed as a mere groomer of hair.

Guild membership also gave barber-surgeons new visibility. They participated in civic pageantry, marched in processions, and maintained halls that rivaled other trades. Their presence in urban life was not just professional but symbolic: they were artisans who claimed a place alongside smiths, weavers, and masons.

At the same time, guilds could restrict as much as they enabled. Apprentices without means were excluded, and rural practitioners often remained outside formal networks. The institutionalization of the craft reflected broader medieval tensions between city and countryside, elite and popular practice.

Conclusion: A Hybrid Legacy

The barber-surgeon’s legacy is one of mixture. He was a hybrid healer, a tradesman whose razor touched both the head and the vein. He was at once despised and sought after, a liminal figure who embodied the blurred boundaries of medieval medicine.

Even today the spinning barber’s pole recalls him. What we see as a symbol of grooming is, in fact, a monument to his medical past. It is the last public sign that once, in the same chair, a man might walk away freshly shaved, or freshly bled.

Appendix

Notes

- Michael McVaugh, Medicine Before the Plague: Practitioners and Their Patients in the Crown of Aragon, 1285–1345 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 112–115.

- Vivian Nutton, Ancient Medicine (London: Routledge, 2004), 246–250.

- John Blair, Pastoral Care before the Parish (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 78.

- Nancy Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 201–206.

- Katherine Park, Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection (New York: Zone Books, 2006), 65–67.

- Andrew Wear, Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 34–39.

Bibliography

- Blair, John. Pastoral before the Parish. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- McVaugh, Michael. Medicine Before the Plague: Practitioners and Their Patients in the Crown of Aragon, 1285–1345. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Nutton, Vivian. Ancient Medicine. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Park, Katherine. Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection. New York: Zone Books, 2006, 206.

- Siraisi, Nancy. Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

- Wear, Andrew. Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.19.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.