Exploring the use and adaptation of the Galenic corpus in the hands of late antique medical compilers.

By Dr. Petros Bouras-Vallianatos

Associate Professor of History of Science

National and Kapodistrian University of Athens

Introduction

Studying the medical literature that was produced from the fourth to the seventh century ad is central to an understanding of how Galen’s corpus impacted on the production of medical works, and to some extent on medical practice, during this early period as well as later, through the reception of the late antique medical literature itself in subsequent periods and in different intellectual environments. The medical literature of this period can be divided into two main categories, each corresponding to the basic purpose the texts were intended to serve. First, the fifth to the seventh century in particular was a period marked by the production of texts of a clearly didactic nature, such as commentaries and summaries, which were connected with the teaching of medicine. These texts aimed to complement the study of the Hippocratic and Galenic works that formed the Alexandrian curriculum.1 Although only a small proportion of these texts survive today in the original Greek, others are accessible through Arabic translations.2 Second, this period also saw the production of medical handbooks in Greek and Latin. These works, although differing in thematic arrangement, levels of expertise, and length, all share a common purpose, viz. to assist their readers in consulting practical recommendations, mainly diagnostic and therapeutic, from a variety of sources in the accessible format of a single work. This chapter explores the use and adaptation of the Galenic corpus in the hands of late antique medical compilers. It is divided into two main sections dealing with Greek and Latin authors respectively.

The Greek Tradition

Oribasios, Aetios of Amida, and Paul of Aegina

In Owsei Temkin’s own words, ‘Oribasios marks the terminus a quo we can safely speak of Galenism in medicine’, emphasising the dependence of the late antique medical system on Galen’s theories and practices.3 Active in the second half of the fourth century, Oribasios is the author of four works, in which a prominent role is indeed given to Galen’s corpus almost a century and a half after the latter’s death, attesting to his growing importance. The efforts of Oribasios must have been crucial in establishing Galen’s works as the main sources for the composition of medical handbooks in Late Antiquity, although, as we will see below, the surviving material often reveals a remarkable pluralism with regard to the selection and use of the available medical sources.

Oribasios was a personal friend and physician of the Emperor Julian (r. 361–3), with whom he seems to have become acquainted during the latter’s exile in Asia Minor; he accompanied Julian on the Persian expedition (363) and looked after him until his death.4 He wrote a synopsis of Galen’s works that does not survive today but, thanks to the Byzantine scholar and patriarch Photios (810–93), its proem is preserved in the latter’s lengthy Bibliotheca.5 From it we learn that this enterprise was undertaken at Julian’s behest. Oribasios’ task was to abridge (syntemein eis elatton) and to create a synopsis (synopsis), to help users, who were not able to delve into the long and very detailed Galenic corpus (adynatōs echousi tous kata diexodon), to gain some Galenic knowledge in a short time, and also to assist those who had acquired the requisite practical skills to quickly be reminded of the essentials (en brachei anamnēseōs tōn anagkaiotatōn genomenēs) in an emergency (chreias epeigousēs).6 What Oribasios was attempting to do had a significant practical purpose: to provide physicians with easily accessible material for immediate consultation. This purpose becomes clearer in looking at Oribasios’ surviving works, i.e. Medical Collections, Synopsis for Eustathios, and For Eunapios.

Each work is shaped by the particular purpose and audience for which it was intended.7 Medical Collections is a massive work written at Julian’s request and originally consisting of seventy books, of which almost one-third have survived. Synopsis for Eustathios, in nine books, was written for Oribasios’ son and can be seen as an abridged version or an autoepitome of the Medical Collections with the specific aim of providing instructions to those who are ravelling or are facing an emergency.8 In For Eunapios, Oribasios again draws heavily on the Medical Collections, but in this case the aim was to provide brief recommendations to his friend, the sophist Eunapios, a philiatros, that is an intellectual with a basic knowledge of medicine, but not a physician himself.9 In tracing and attempting to understand Galen’s presence in Oribasios’ work, I will focus on the Medical Collections.

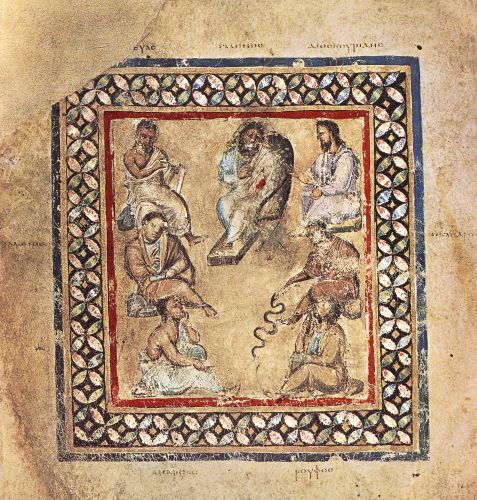

Oribasios himself calls his work a collection (synagōgēn) of all the available knowledge that is useful for the purpose of medicine (telos tēs iatrikēs).10 In fact, the arrangement of topics in the surviving books shows a meticulously comprehensive treatment of a large number of topics, including dietetics, pharmacology (simple and composite drugs, with a separate section on purgatives), bathing, anatomy, treatment of inflammations, ulcers and tumours, orthopaedics, and invasive surgery (mainly hernia). With the exception of Galen, who is singled out as the most important medical authority, Oribasios was not eager to name his sources in the proem.11 Indeed, the Galenic corpus receives the lion’s share of the available space. However, as Roberto de Lucia has observed, Oribasios often supplemented his work with excerpts from other authors, in an attempt to complement Galen’s account when it is deficient on a particular topic. For example, book 24 mainly consists of passages from On the Function of the Parts of the Body and On Anatomical Procedures, with the occasional addition of small excerpts from other Galenic works, such as On the Organ of Smell, together with a chapter by Soranus (second half of the first century/early second century AD) on the female genitalia.12 On another occasion, in book 1, Oribasios combined material from more than one Galenic treatise on the same topic (e.g. on grains) in such a way that one Galenic text (On Good and Bad Humours) complements another (On the Capacities of Foodstuffs). He also included an excerpt from Athenaeus (first century BC or c. 50 AD), for a discussion on the impact of climate on the quality of seeds, something not found in any surviving Galenic treatise.13 Apart from Galen, the sources most frequently cited are Dioscorides (first century AD) and Hippocrates, fol-lowed in descending order by Antyllus (ca. first half of the second century AD), Rufus (c. ad 100), Heliodorus (ca. first century AD), Herodotus (first century AD), Zopyrus (c. 100 BC), Soranus, Archigenes (second half of the first century – first half of the second century AD), Athenaeus, Dieuches (third century BC), Diocles (c. first half of the fourth century BC), and Philagrios (first half of the fourth century AD).14 In many cases, Hippocrates is cited second-hand through Galen.15

Also of note, in some cases Oribasios preferred another source to the Galenic account on a certain subject. De Lucia points out a case in which Oribasios included a passage from Antyllus related to the usefulness of exercise, especially running, to one’s health,16 without providing supporting Galenic material on the subject. Given Galen’s criticism of excessive physical exercise (with the emphasis on running), which he says produces an imbalance in the bodily state,17 such an omission might not be coincidental. Thus, Oribasios was the first author to amalgamate Galenic works with those of other ancient physicians, complementing his master’s ideas even with the work of authors whom Galen clearly disparaged in his own works, such as Archigenes and Athenaeus.

The second author is Aetios, a native of Amida,18 who lived in the first half of the sixth century. There is some debate over whether he was ever at the court of Constantinople,19 but there is no evidence of this in any surviving sources, including Aetios’ own text. Similarly, the appellation komēs tou Opsikiou found in some late manuscripts is dubious.20 His medical treatise, usually called Libri medicinales or Tetrabiblos, consists of sixteen books covering the following topics: pharmacology, dietetics, surgery, prognostics, general pathology, fever and urine lore, ophthalmology, cosmetics, dentistry, toxicology, gynaecology, and obstetrics. Out of the sixteen books, only the first eight have been published in a modern critical edition. Some parts of the remaining books remain unpublished or can only be accessed in questionable editions.21

The work lacks a programmatic statement on the author’s intentions such as that found in Oribasios’ works, but some manuscripts transmit a small paragraph naming some of Aetios’ sources, including Oribasios’ works in addition to those of Galen, Archigenes, and Rufus.22 On the whole, Aetios was noticeably less dependent on Galen than was Oribasios. Among the most frequently cited Galenic texts are: On the Capacities of Simple Drugs, On the Composition of Drugs According to Kind, On the Composition of Drugs According to Places, On the Preservation of Health, On Affected Parts, and Therapeutics to Glaucon, with occasional mentions of other treatises such as On the Different Kinds of Fevers, On Crises, and On Treatment by Bloodletting.23 Interestingly, Oribasios is often mentioned as one of Aetios’ sources, alongside frequent references to Dioscorides, Hippocrates, Antyllus, Rufus, Soranus, Archigenes, Herodotus, Philumenus (second/third century AD), and many other minor authors,24 including a certain Andrew the Count (komēs) and a female author called Aspasia.25 There are also recipes attributed to Jewish prophets, Egyptian kings, and Christian apostles and bishops.26 Compared to Oribasios, Aetios sometimes seems less dependent on Galen for his citations of Hippocratic material.27 Aetios’ heterogeneous assemblage of sources, reflecting various therapeutic trends of his day, looks even more dynamic in light of the considerable number of references to the use of amulets made of either mineral, vegetal, or animal ingredients included indiscriminately in his discussion of ‘mainstream’ therapeutics.28 As we will see below, Alexander of Tralles also made use of this kind of material. Although Galen made a few references to amulets, he mostly rejected their use.

Our next author, Paul of Aegina, practised in Alexandria and probably remained there even after the Arab invasion of 642.29 His only extant work in Greek is a seven-volume manual dealing with dietetics, fevers, and diseases arranged in a a capite ad calcem (from head to toe) order, dermatology, bites by venomous animals and antidotes for poisons, surgery and pharmacology. Paul’s aim, in contrast to that of Oribasios and Aetios of Amida, was to provide an abridged version of the most up-to-date medical knowledge for immediate consultation that could be carried everywhere by physicians in the way contemporary lawyers carried vade mecum of legal synopses.30 In his proem, Paul recalls Oribasios’ wording, referring to his work as a collection (synagōgēn), and makes a nice digression to comment on the works of his predecessor, i.e. Oribasios’ lost synopsis of Galen’s works, Medical Collections, and the Synopsis for Eustathios. He says that the Medical Collections is large and not easy to procure, and he notes that Synopsis for Eustathios omitted accounts of many diseases.31

The first two books of Paul’s epitome are for the most part based on either Oribasios or Galen; On the Capacities of Foodstuffs is a main source for book 1, while in book 2 there are quotations from a large number of Galenic treatises, including, for example, On Critical Days, On Crises, Therapeutics to Glaucon, On the Different Kinds of Fevers, and various texts on the pulse. Galen’s main pharmacological works (On the Capacities of Simple Drugs, On the Composition of Drugs According to Kind and On the Composition of Drugs According to Places) appear consistently in the next few books along with quotations from his massive Therapeutic Method. Perhaps, book 6, dealing with surgery, was the single most influential part of Paul’s work.32 In it, Paul often quotes from various now-lost accounts on the subject by authors such as Antyllus and Leonides (c. first century AD), whereas, apart from a few quotations from the Therapeutic Method, he rarely mentions Galen. Galen stated in the Therapeutic Method that he intended to write a manual on surgery, Cheirourgoumena, but he never realised this project.33

The ways in which Oribasios, Aetios, and Paul integrated parts of the Galenic corpus into their own writings varied. Philip van der Eijk has aptly shown that Oribasios, in incorporating in his Medical Collections (book 1, chapter 28) an account on animal meat from Galen’s On the Capacities of Foodstuffs, managed to condense the Galenic original without omitting any information essential to his reader’s understanding of the passage. For example, having retained the Galenic statement on the nutritional value of pork (‘pork is the most nutritious [meat]’), Oribasios left out the other sentences in which Galen had provided evidence of this by discussing the diet of athletes.34 Aetios (book 1, chapter 121) seems to have followed Oribasios in this regard, although he occasionally var-ied his approach by, for example, also using brief excerpts from Galen’s On the Capacities of Simple Drugs at the beginning and end of certain chapters.35 In the case of Aetios, Galen’s name also appears in the relevant chapter title (‘On meat from Galen’), which could be seen as a user-friendly reference tool for any reader wanting to locate a chapter on a particular topic while leafing through the codex.36 Finally, Paul (book 1, chapter 84) created a dramatically abridged text, including only absolutely essential information, which contains laconic statements on some basic characteristics of the most common kinds of meat (e.g. ‘beef gives rise to melancholy’), but omits references to, for example, the meat of bears, lions, leopards, and dogs that had been retained by Oribasios and Aetios. These careful selection processes and re-arrangements of the Galenic material, which might have been influenced by the authors’ own experiences, led to the production of easily accessible, abridged lists of Galenic recommendations. The re-arrangement of the Galenic information might sometimes also have functioned as an aid for the readers, helping them to better understand complex theoretical notions. For example, John Scarborough has argued that Oribasios’ and Aetios’ arrangement of Galenic citations on pharmacology involved a certain amount of clarification of the complex Galenic system of drug classification based on degrees of intensity of the primary qualities.37 Thus, apart from transmitting and promoting their master’s advice to their contemporaries, they also gave a practical new twist to Galenic knowledge.

Alexander of Tralles and the Early Criticism of Galen

The sixth-century practising physician Alexander of Tralles requires special attention.38 He came from a prominent provincial family; his father Stephen was a physician in Tralles, in Asia Minor, and his brother Anthemios was the architect of the great church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. Alexander is the author of three works: Therapeutics, On Fevers, and On Intestinal Worms. His magnum opus, Therapeutics, consists of twelve books and deals with the diagnosis and therapy of diseases, often supplemented with details on symptomatology and prognosis, in an a capite ad calcem arrangement. Unlike in Paul’s work for example, there is no discussion of invasive surgery, because Alexander believed it to be a form of torture rather than a treatment.39 His monograph On Fevers provides an extensive treatment of the subject and complements Therapeutics. The short preface that precedes On Fevers in Theodor Puschmann’s critical edition offers insight into the author’s intentions:

although I am now an old man no longer able to exert myself greatly, I obeyed and wrote this book, after having collected my experiences (peiras) from my many contacts with human diseases.40

Alexander presents himself as a practising physician at an advanced age, who is eager to share his knowledge with future fellow practitioners. Unlike the cases with other late antique Greek compilers, Alexander’s persona is obvious throughout his works, which are pervaded by his frequent interventions in the first-person singular, transmitting an observation or a report derived from his practical experience (peira), thus reinforcing the credibility of his advice to his readers.41 In fact, independence of mind characterises Alexander’s writing style, allowing him to often take a critical stance towards Galen’s theories.

Alexander adopted an eclectic approach to citing earlier sources, some-times supplementing them with his own contributions, most conspicuously in the field of pharmacology.42 Galen is by far the medical author most frequently cited by name, with excerpts from his works or evidence of influence from works such as Therapeutics to Glaucon, On the Differences of Fevers, Therapeutic Method, On Affected Parts, On the Capacities of Foodstuffs, and his pharmacological treatises on simple and composite drugs. Hippocrates is the second most-cited author, with Alexander providing a good number of direct citations from the Hippocratic corpus, including works such as Aphorisms, On Nutrition, and On Regimen on Acute Diseases. Archigenes is the third most-cited named source. Alexander also refers to a large number of other authors, including well-known ones, such as Erasistratus (c. 315–c. 240 BC), Rufus, and Philagrios, and minor or marginal authors, mostly connected with recommendations for natural remedies (physika), such as Asclepiades Pharmakion (c. second half of the first century AD), Xenocrates of Aphrodisias (second half of the first century ad), Straton of Beirut (c. first century AD), Moschion (c. first/second century AD), Didymus (fourth/fifth century AD), and obscure authors, such as Osthanes (c. first century BC).43 Sometimes one can also detect references to Methodism.44

Admittedly, the most intriguing part of Alexander’s recommendations are the so-called natural remedies.45 These can include diagnostic and therapeutic advice related, for example, to the use of amulets and incantations or the use of a gladiator’s rag imbued with blood, which had been burnt and mixed with wine. Apart from the above-mentioned authors, Alexander sometimes refers to natural remedies that he had learnt about from people living in the countryside during his trips to Spain, Gaul, Italy, and Corfu. He differentiated these remedies clearly from the other parts of his work with special subheadings. Furthermore, unlike, for example, Aetios, who make no attempt to justify the material he included, Alexander consistently attempted to provide a reason for his decision to use such remedies, although he often appears apologetic about it. On one occasion, Alexander reports that he had learned more about these natural remedies, because some wealthy patients, having refused a painful method of purgation using enemas, had asked him to cure them by means of amulets, probably alluding to other healers who suggested such treatments.46 This emphasises another aspect of medical practice that informed Alexander’s thinking and approach: the intense competition among various kinds of practitioners that may have forced him to heal using ‘every possible means’, as he himself honestly admits.47 However, he is occasionally eager to confirm to his readers that his experience (peira) has proven that many such remedies eventually worked, thus suggesting he actually embraced natural remedies as part of his diverse medical cabinet.

Having briefly sampled Alexander’s sources, we can now go on to look more closely at Galen’s presence in his works. Alexander very often uses the terms theiotatos (most divine) and sophōtatos (most wise) in reference to Galen, to convey his admiration for the Pergamene physician.48 He also uses the appellation theiotatos at times in referring to Hippocrates and does so once in regard to Archigenes; furthermore Didymus, the author of the so-called Octateuch, is called sophōtatos on one occasion.49 Before attempting to provide an explanation for Alexander’s decision to elevate Archigenes and Didymus to the same status as Galen and Hippocrates, it is worth dividing the Galenic citations in Alexander’s work into three main groups. First are cases in which Alexander has been influenced by Galen but does not refer to him by name. Second are examples in which Alexander provides a reference to a piece of Galenic advice and explicitly mentions his master by name; here Galen is sometimes used as an authority on a certain subject to support Alexander’s use of a particular recommendation. Third are the cases in which Alexander does not hesitate to disagree with Galen’s views.

In the first group, we can see an example in book 1, chapter 15, of Therapeutics, in which Alexander refers to a young patient suffering from epilepsy originating in the lower limbs. His section on symptomatology resembles a Galenic case history from On Affected Parts, but Alexander pays special attention to therapy, by introducing the use of a simple drug, pepperwort (lepidion), which is not mentioned in the Galenic passage.50 This confirms Alexander’s eagerness to elaborate on the material already available, supplementing it with the fruits of his rich practical experience in line with his programmatic statement mentioned above.

As regards the second group, I have compared elsewhere Alexander’s approach in book 3 of his On Fevers with those of Oribasios (For Eunapios) and Aetios in using an excerpt from Galen’s Therapeutics to Glaucon focusing on the diagnosis and treatment of leipothymia (a temporary loss of consciousness).51 Subsequently, I have shown that, much like Aetios, Alexander divided the Galenic account into sub-sections by providing chapter headings, thus showing a notable concern for his readers. Alexander also provides a direct reference to Galen in the heading preceding his account, calling him ‘most divine’ and thus emphasising his authority. However, Alexander often adopted a different approach from that of Oribasios and Aetios, by appropriating larger excerpts from the Galenic account and showing a particular interest in those parts dealing with diagnosis and aetiology. Interestingly, on one occasion Alexander, unlike Oribasios and Aetios, supplements the Galenic account with a brief piece of qualitative advice (‘and in this way you can diagnose precisely’), in an attempt to emphasise its usefulness to his reader in his own personal way. In another case, in discussing the treatment for inflammation of the auditory canal, Alexander cites the Galenic advice from On the Composition of Drugs According to Places, stating: ‘Let it happen just as the most divine Galen says. His [i.e. Galen’s] statement is as follows: “I do not infuse any drug for those suffering …”’.52 Unlike, for example, Aetios, who often reproduces first-person pronouns indiscriminately, here Alexander clearly differentiates Galen’s state-ment from his own account.

Moreover, Galen is sometimes invoked to back up Alexander’s view on the efficacy of a certain piece of advice, a sign of Galen’s supreme position and authority in the sixth century. For example, in discussing the treatment for phrenitis, Alexander criticises those physicians who administer drugs to the inner parts of the body or topical treatments, such as plasters, at any time, including in cases of indigestion (apepsia). In order to substantiate his view, Alexander refers to Galen’s corresponding statement in the Therapeutic Method, as Alessia Guardasole has pointed out,53 by stating:

the most wise Galen clearly declares that neither plasters nor fomentations should be used at any time, except in those [patients] where the superfluity has not yet spread to the entire body; in all other [patients] the harmful effect is extreme.54

The last case I would like to mention here is related to the use of natural remedies. In an attempt to justify the use of incantations, Alexander states:

and the most divine Galen, who did not believe in incantations, after many years and due to his long experience discovered that they might be extremely helpful. Listen to what he said in the treatise On Medicine According to Homer. This is what he says: ‘And so some believe that incantations resemble old wives’ tales, and that was my own belief too until recently; [but] over time, I have been convinced by the visible effects that there is some power in them …’. Since both the most divine Galen and many other ancient authors attested to this, what prevents us from presenting these [i.e. the natural remedies] which we have learned by experience and through true friends?55

Although Galen is not always as rational as some once believed, his support for incantations in Alexander’s sense nonetheless seems unlikely,56 and the aforementioned Galenic work should most probably be considered pseudepigraphic.57 Consequently, Alexander’s favouring of Archigenes and Didymus is not a coincidence. Archigenes, in particular, unlike Galen, is a well-known ancient medical authority who made consistent use of natural remedies.58 With regard to Alexander’s reference to what is now thought to be a pseudo-Galenic work, it is worth remembering that even later in the Middle Ages, well-educated intellectuals were sometimes not able to differentiate between genuine works by Galen and pseudepigraphic ones.59

The last and most significant group is that in which Alexander is clearly at odds with one of his master’s views. Although Alexander sometimes mentions Hippocrates’ name to invest his own words with authority as he did with Galen,60 he never criticised the Koan physician. In one of the most notable instances, Alexander, in discussing the treatment of ephemeral fevers, expresses dismay that Galen recommends using warming agents for those suffering chronic indigestion (apepsia):

For if the greasy belching and indigestion happened due to heat, it is then clear that it will be increased if we attempt to use warming agents. And thus, it seems amazing to me how the most divine Galen in his therapeutic treatise [i.e. Therapeutic Method] seems to use warming agents. For he allows the antidote made from the three peppers and the one made from quince to be given, and also to apply the [marine] purple with spikenard, wormwood, and mastic to be applied externally to the stomach … Ι (egō) do not believe that these [recommendations] are fitting for those having a warmer disposition; and I say this without intending to disagree, but simply to state what seems true (alēthes) to me. For what is true (alēthes) must always be preferred above all else. For if the greasy belching and indigestion is caused by heat, I think it is necessary to use the opposite in order to cure it.61

Alexander refers to a passage in the Therapeutic Method, in which Galen discusses the corresponding treatment.62 His objection is based on Galen’s failure to use a cold agent to counterbalance the chronic heat. Alexander uses a strong first-person singular statement to communicate his opinion to his readers. Using the term ‘true’ (alēthes) lends even greater emphasis to the author’s own contribution by attempting to present the Galenic advice as wrong and unreliable.63

Even more intriguing are those cases in which Alexander accuses Galen of not having provided essential information or of giving rather vague advice. We have mentioned before a case in which Alexander cites a piece of Galenic ad-vice in his chapter on the treatment of inflammation of the auditory canal. Having cited an excerpt from Galen, he goes on to state:

And so, Galen wrote this, advising to us that we must use this [i.e. fomentation] for every painful inflammation, without making it [i.e. his advice] more specific (mēden prosdiorisamenos). As I (egō) have already told you, I prescribe this to young people with a hot krasis, where the inflammation is associated with high temperature and often even with fever, especially if it is in summertime and the patient falls ill in a warm place. But it is better, if you are obliged to use the fomentation due to the extreme severity of the pains, to administer the fomentation with a sponge that has been immersed in hot water.64

Galen describes a detailed procedure using a special probe (mēlōtis) to infuse some drugs into the ear that also includes a fomentation stage. Once again, by using a first-person singular pronoun to emphasise the point, it would seem that Alexander feels the process of fomentation needs further clarification, which he eagerly provides based on experience he has gained after long-term contact with patients. In another, similar case, Alexander is keen to show that some antidotes, such as the Cyrenaic juice,65 should not be used in every instance – having been incorrectly recommended by Galen – and cites some examples derived from his own experience:

And the most divine Galen set [this] out, but without providing any specifications (prosdiorisamenos); because of this many [physicians] have relied on these recommendations and given these [antidotes] indiscriminately, thus causing a very great damage and extreme danger [to the patients].66

Here, unlike in the other cases, Alexander refers also to those who followed Galen’s advice without revising it in line with their practical experience like he did. Judging by Alexander’s account, it seems that Galen was perceived as an infallible authority by Alexander’s contemporaries. Alexander, writing three centuries or so after Galen’s death, is the first author who did not hesitate to expose Galen’s weaknesses, even though they were few in number given the vast size of his corpus.

The last example I shall present will also give us the opportunity to better understand Archigenes’ role in Alexander’s work. Alexander discusses the diagnosis and therapy of a patient suffering from thick, gluey pulmonary humours. First, Alexander criticises Galen, once again hailed as ‘most divine’, for not being able to accurately describe a certain stone (lithos) that could be expectorated from a patient’s mouth and that made a noise when it hit the ground, a simple reference to a hailstone (chalazion).67 Afterwards, Alexander considers Galen’s advice on the use of warming agents inappropriate and finally comes up with his own composite drug for the purpose. Addressing Galen, he states:

His [Galen’s] statement about Archigenes is indeed true: ‘it is hard for a man not to be mistaken about many things, about some of which he is completely ignorant, some because he judges them wrongly, and others because he had treated them carelessly’. I would not dare to say these [things] of such a wise man [i.e. Galen], if truth had not given me the courage, and in addition I would have considered [it] disrespectful to remain silent.68

Alexander contrives a respectful way to mitigate his criticism of Galen by appropriating his master’s own words.69 It seems that this particular quotation from Galen’s On the Composition of Drugs According to Places has not been used at random.70 This could be seen as an attempt to temper Galen’s often-critical attitude towards Archigenes, and thus serve as an emphatic pointer to Alexander’s readers when consulting other parts of his treatise where he not only makes use of outlandish medical recommendations that can be classified as natural remedies (physika), but even calls Archigenes ‘most divine’.

The Latin Medical Handbook

The late antique period also witnessed the production of medical handbooks in Latin to serve the western Mediterranean. Direct dissemination of the Galenic corpus in Latin is very limited in this early period, mainly restricted to a few translations of such works as On Sects for Beginners and Therapeutics to Glaucon,71 and its indirect transmission through translations into Latin of late antique Greek medical works, including those by Oribasios.72 The absence of Galen from the pharmacologically focused manuals Medicina Plinii (c. fourth century AD) and On Drugs by Marcellus of Bordeaux (fl. early fifth century AD) is not surprising, since in both cases there is a strong preference for Latin sources.73 Galen is also not cited in the Acute and Chronic Diseases by Caelius Aurelianus (fifth century AD), the Methodist medical author and compiler of Soranus’ Greek works into Latin, although Caelius often cites the recommendations of other Greek authors, such as Hippocrates, Diocles and Praxagoras (fourth/third century BC), despite disagreeing with them. Galen’s absence from Caelius’ works could perhaps be explained by the unavailability of Soranic disputations on the Pergamene physician.74 There are only two authors who seem to have appropriated Galenic material at some length in their works: Theodore Priscianus and Cassius Felix.

Theodore Priscianus, most probably active in the late fourth/early fifth century ad, was a physician and student of the prominent North African politician and physician Vindicianus. The only works of his to survive are a collection of remedies, the so-called Euporista, along with the preface and two chapters from Physica, both works in Latin. Euporista belongs to the well-established tradition of the euporista or, in Latin, parabilia, referring to easily procurable remedies that could be used by travelling physicians or even non-specialists with an elementary knowledge of medicine. It is a practical work consisting of three books, each following an a capite ad calcem arrangement. The first, Faenomenon, and the second, Logicus, deal with affections of the inner and outer parts of the body respectively, while the third, Gynaecia, focuses on women’s diseases. Theodore had written works in Greek, and although it has been claimed that Euporista is based on a translation of his own Greek original,75 David Langslow has rightly noticed that this is not explicitly stated in Theodore’s preface.76 Greek was not so widely understood in the West by the fourth century, thus Theodore’s project must be seen as an attempt to address a broad audience.77

Galen is never mentioned by name in Theodore’s work, unlike Hippocrates, who appears a couple of times, mostly alluding to a certain Aphorism.78 I think Galen’s absence could be explained in this case by Theodore’s general tendency throughout his work not to name his sources. There are, however, parts that closely resemble passages from Galen’s works. For example, in the Faenomenon, there are occasionally very close parallels with recipes from Galen’s On the Composition of Drugs According to Places, On the Composition of Drugs According to Kind, and On the Capacities of Simple Drugs.79 A thorough grounding in Galen, combined with Methodist sources, such as Soranus,80 is regularly detectable in book 2, which shows familiarity with other Galenic works, including the Therapeutic Method and On Affected Parts as well as the pseudo-Galenic On Procurable Remedies.81

A more obvious case of adopting Galenic material is that of Cassius Felix, a physician from North Africa, active in the first half of the fifth century ad. His On Medicine is a practical handbook consisting of eighty-two chapters providing information about the definitions, symptoms, causes, and treatment of various diseases arranged in an a capite ad calcem order.82 The work is dedicated to his son, presumably a physician, and unlike Theodore’s Euporista, was clearly aimed at the specialist who also had some understanding of Greek.83 Furthermore, unlike in Theodore, where surgery is limited to the use of phlebotomy, here one finds advice on invasive surgery, such as the removal of an abscess using a rounded cut (strongylotomian) or the use of a special instrument (the so-called syringotomo) for operating on fistulae,84 although Cassius does not refer to complicated techniques such as trephination. The brief na-ture of Cassius’ advice clearly suggests a background in the required surgical skills on the part of his reader. Intriguingly, there are some cases in which natural remedies, including the use of amulets, are recommended, but often as a last resort.85 Cassius declares in his preface that his intention is to provide the medical knowledge of the Greek authors of the Dogmatic or “logical” school (ex Graecis logicae sectae) in brief (in breuiloquio) in Latin.86 Of the sources named throughout his work, Hippocrates and Galen are by far the most often cited, followed by Philagrios and Vindicianus (fl. second half of the fourth century AD). Methodism also has a significant presence, although Cassius never refers to any author of this school by name.

The use of Hippocrates is limited to eleven brief references from Aphorisms and two from Prognostic. Of these, two are cited using Galen and another two seem to have been known through the corresponding Hippocratic commentary on the Aphorisms by the Alexandrian iatrosophist Magnos, who is explicitly mentioned.87 Although Galen’s name is only cited seventeen times, there is extensive use of Galenic material throughout the treatise, mainly focused on therapeutic recommendations from his three pharmacological works (On the Composition of Drugs According to Places, On the Composition of Drugs According to Kind, and On the Capacities of Simple Drugs) and his Therapeutics to Glaucon, especially the sections on fevers. The vast majority of Galenic passages in Cassius’ work are transmitted in translation without considerable variation.88 Nevertheless, as Anne Fraisse has shown, there are times when one can spot Cassius’ intentional interventions, such as when he supplements the Galenic therapeutic indications for a certain composite drug or reduces the number of ingredients in a composite drug to perhaps make it less expensive or more easily obtainable, and thus more accessible to his readers,89 who are now able to access Galen alla Latina.

Conclusion

The authors of late antique medical handbooks made significant efforts to not only transmit but to select, abridge, and rearrange Galen’s works in a useful and practical manner. The process of adaptation was not a mechanical one and these authors were not simply ‘refrigerators’ of classical knowledge, as they were once described.90 On the contrary, their compiling methods attest to an intellectual process that aimed to enhance consultation of an otherwise vast corpus, thus making Galen available to contemporary practitioners in an accessible format. Interestingly, among the most often cited Galenic works are the pharmacological texts,91 which were excluded from the more theoretically oriented Alexandrian curriculum. It has also been pointed out that late antique authors often mixed Galenic excerpts with texts from other ancient authors, revealing an often-remarkable pluralism. The persistence of Methodism, in particular in the West, shows that the spread of Galenism was not as instant and far-ranging as one might imagine. Furthermore, the works of the Hippocratic corpus, although often approached through Galen, were also consulted in their own right in a number of instances.

The use of authors who had been strongly criticised by Galen (e.g. Athenaeus and Archigenes) shows a striking independence in the selection process. This independent attitude is even more evident in the works of Alexander of Tralles, whose enthusiasm was always supported by a wealth of personal observations derived from treating his own patients. Alexander attempted to promote himself as a most capable practising physician, and therefore someone with sufficient experience and knowledge to critique the incontestable Galen. His inquisitive spirit, however, never led him to make a systematic attempt at undermining Galen’s authority, unlike, for example, the eleventh-century Byzantine author Symeon Seth, who wrote a short treatise specifically criticising him.92 Unlike Symeon, Alexander was a vigilant practising physician, who having benefited considerably from reading and using Galen’s advice, nevertheless felt sufficiently confident in his own judgment to suggest revisions, thus improving its practical application.

Appendix

Endnotes

- On this group of texts, see Garofalo (Chapter 3) in this volume. All translations are mine. The exact dates of medical authors are rarely known, and the dates cited are approximations following Leven (2005).

- See the new study by Overwien (2018). There are also surviving commentaries in Latin, most probably produced by scholars based in sixth-century Ravenna; see Palmieri (2001).

- Temkin (1973: 64).

- See de Lucia (2006: 21–9).

- On Photios’ discussion of Oribasios’ works, see Marganne (2010: 516–18). See also Stathakopoulos (Chapter 7) in this volume, who discusses the Bibliotheca in the framework of Galen’s reception in non-medical Byzantine sources.

- Photios, Bibliotheca, Codex 216, ed. Henry (1962) III.131–2.

- On late antique medical compilations in the framework of ancient and late antique summaries and compilations of technical works, see the recent overview by Dubischar (2016: 432–5).

- Oribasios, Synopsis for Eustathios, pr., ed. Raeder (1926) 5.7–13.

- Oribasios, For Eunapios, pr., ed. Raeder (1926) 317.2–25. On philiatroi, see Luchner (2004). One prominent ancient philiatros was Glaucon, to whom Galen dedicated his Therapeutics to Glaucon; on this, see Bouras-Vallianatos (2018: 180–3).

- Oribasios, Medical Collections, pr., ed. Raeder (1928) I.I .4.3–9.

- Oribasios, Medical Collections, pr., ed. Raeder (1928) I.I .4.13–16.

- De Lucia (2006: 28–9).

- De Lucia (1999a: 481–2). See also Scarborough (1984: 221–2), who discusses how Oribasios combined Galenic accounts on simple drugs with accounts by Dioscorides.

- De Lucia (1999a: 484–5). In the index of Raeder’s edition (1933: II.II.308–35) of Oribasios’ surviving corpus, although it is not entirely comprehensive (cf. de Lucia, 1999: 484, n.24), the references to the Galenic corpus take up sixteen pages compared to just two and a half pages for Dioscorides and one page for the Hippocratic corpus.

- De Lucia (1999b: 448–50).

- De Lucia (1999a: 487–8). Oribasios, Medical Collections, 6.24, ed. Raeder (1928) I.I .179.28–180.20.

- Galen, Parv. Pil., 3, ed. Kühn (1823) V.906.3–5 = ed. Marquardt (1884) 98.21–3. Cf. König (2005: 274–91). In his Exhortation to the Study of the Arts, 9–14, ed. Kühn (1821) I.20.4–39.10 = ed. Boudon (2000) 100.1–117.18, Galen attacks athletic excess, since he believed that only moderate exercise could produce bodily health and virtue in the soul; on this, see Xenophontos (2018: 76–9).

- Amida, a Mesopotamian city on the Tigris River, modern-day Diyarbakir, in Turkey.

- Cf. Scarborough (2013).

- Cf. Hunger (1978: II.294).

- Garzya (1984).

- Olivieri, Tetrabiblos, pr., ed. Olivieri (1935) I.10.1–4.

- It is worth noting that Aetios often reproduces the first-person personal pronouns of his sources, thus making it impossible to differentiate between the work of the original authors and that of the excerptor; see Debru (1992). An interesting case related to Aetios’ supposed travels to Syria, 2.

- ed. Olivieri (1935) I.164.15ff, and Cyprus, 2.64 ed. Olivieri (1935) I.174.4ff, recently mentioned by Romano (2006: 256). These are not genuine, but reflect quotations from Galen: SMT, 10.2.10, ed. Kühn (1826) XII.203.9ff and 10.3.21, ed. Kühn (1826) XII.226.11ff respectively.24 On Aetios’ sources, see Bravos (1974).

- On Andrew and Aspasia, see Calà (2012b) and Flemming (2007: 270) respectively. See also Calà (2012a: 40–8).

- See Martelli in Eijk et al. (2015: 203–4); and Calà (2016a).

- De Lucia (1999b: 450–4).

- Calà (2016b); and Mercati (1917).

- On Paul, see Pormann (2004: 4–8).

- Paul of Aegina, Epitome, pr., ed. Heiberg (1921) I.3.8–16.

- Paul of Aegina, Epitome, pr., ed. Heiberg (1921) I.3.24–4.17.

- Tabanelli (1964).

- Galen, MM, 14.13, ed. Kühn (1825) X.987.13.

- Van der Eijk (2010: 536–46).

- Aetios’ work may have been based on Oribasios’ lost synopsis of Galen’s works or some other now-lost compiled manual; see Sideras (1974) on this. Van der Eijk (2010: 545) suggests that Aetios himself could also have been responsible for this re-arrangement. Some more examples are offered by Capone Ciollaro and Galli Calderini (1992); and de Lucia (1996).

- See de Lucia (1999a: 483, n.20) and MacLachlan (2006: 105–9), who both argue convincingly for the originality of the chapter headings in the works of Oribasios.

- See Scarborough (1984: 221–6). The Galenic classification was also an issue of debate in the medieval Islamic medical tradition; on this, see Chipman (Chapter 16) in this volume.

- For an introduction to Alexander of Tralles and his works, see Puschmann (1878: I.75–87); Guardasole (2006: 557–70); and Langslow (2006: 1–4).

- Alexander of Tralles, Therapeutics, 1.15, ed. Puschmann (1878) I.575.6–9.

- Alexander of Tralles, On Fevers, pr., ed. Puschmann (1878) I.298.8–10.

- Bouras-Vallianatos (2014: 341–2).

- Scarborough (1984: 226–8); and Bouras-Vallianatos (2014: 344–8).

- For a full list, see Puschmann (1879: II.600).

- See the references to the notion of metasynkrisis throughout Alexander’s work; for example, Therapeutics, 1.15, 1.16, and 7.3, ed. Puschmann (1878–9) I.557.5, I.579.16, and II.253.17–18. For a brief discussion of metasynkrisis, see Rocca (2012).

- See Guardasole (2004a); and Bouras-Vallianatos (2014: 348–52).

- Alexander of Tralles, Therapeutics, 8.2, ed. Puschmann (1879) II.375.10–16.

- Alexander of Tralles, Therapeutics, 1.15, ed. Puschmann (1878) I.573.1.

- Interestingly, the term theiotatos was also used by Galen with reference to Hippocrates; on this, see Boudon-Millot (2014).

- Bouras-Vallianatos (2016: 388).

- Bouras-Vallianatos (2014: 346–7).

- Bouras-Vallianatos (2018: 194–7).

- Alexander of Tralles, Therapeutics, 1.13, ed. Puschmann (1879) II.81.23–5; cf. Galen, Comp. Med. Loc., 3.3, ed. Kühn (1826) XII.603.2–604.8.

- Guardasole (2004b: 227–8). Galen, MM, 11.15, ed. Kühn (1825) X.781.12–14.

- Alexander of Tralles, Therapeutics, 1.13, ed. Puschmann (1878) I.523.1–5.

- Alexander of Tralles, Therapeutics, 11.1, ed. Puschmann (1879) II.475.4–15.

- See, for example, his statement in the SMT, 6.pr, ed. Kühn (1826) XI.792.10–793.2.

- On the pseudepigraphy of this treatise, see Kudlien (1965: 295–9). Cf. Jouanna (2011: 70–1 and n.22).

- Bouras-Vallianatos (2016: 389–94). See also, Alexander of Tralles, Therapeutics, 7.9, ed. Puschmann (1879) II.319.8–11.

- See, for example, Petit (2013: 66–8), who informs us that in some manuscripts connected with the circle of the prominent fifteenth-century Byzantine philosopher John Argyropoulos, the long pseudo-Galenic Introduction, or the Physician is consistently ascribed to Galen.

- See, for example, Alexander of Tralles, Therapeutics, 6 and 8.2, ed. Puschmann (1879) II.231.11–13 and II.377.26–8.

- Alexander of Tralles, On Fevers, 1, ed. Puschmann (1878) I.301.10–22.

- Galen, MM, 8.5, ed. Kühn (1825) X.570.17–577.4.

- See also Alexander of Tralles, Therapeutics, 5.4, ed. Puschmann (1879) II.155.20–22; and Guardasole (2004b: 222–7).

- Alexander of Tralles, Therapeutics, 3.2, ed. Puschmann (1879) II.83.15–22.

- Galen, MMG, 1.12, ed. Kühn (1826) XI.40.

- Alexander of Tralles, On Fevers, 7, ed. Puschmann (1878) I.421.4–6.

- Cf. Galen, Loc. Aff., 4.11, ed. Kühn (1824) VIII.291ff.

- Alexander of Tralles, Therapeutics, 5.4, ed. Puschmann (1879) II.155.13–18.

- See Bouras-Vallianatos (2016: 385–6).

- Galen, Comp. Med. Loc., 2.1, ed. Kühn (1826) XII.535.4–6.

- The Art of Medicine may also have been translated into Latin; see Fischer (2013: 694–5). On Therapeutics to Glaucon, see Fischer (2012).

- Baader (1984). See also the recent study by Buzzi and Messina (2014) with references to previous bibliography, in particular, on Latin translations of Oribasios; cf. Fischer (2013: 688–9).

- On these two works, see Doody (2009) and Stok (2008) respectively.

- Urso (1997: 9); and Eijk (1999: 432).

- Önnerfors (1993: 288); and Formisano (2004: 129).

- See Langslow (2000: 55–6), who also thinks that Theodore’s first language was Greek. Cf. Theodore Priscianus, Faenomenon, pr., ed. Rose (1894) 1.1–2.4.

- On Theodore Priscianus, see Langslow (2000: 53–6); and Formisano (2001: 74–84).

- E.g. Theodore Priscianus, Faenomenon and Logicus, 16 and 25, ed. Rose (1894) 51.1–5 and 121.14–17; [Hippocrates], Aphorisms, 5.18 and 2.42, ed. Littré (1844) IV.482.7–8 and 538.3–4 = ed. Jones (1931) 162.1–3 and 118.11–12.

- See Fraisse (2003: 185–6).

- Migliorini (1991).

- Cf. the apparatus criticus in Rose’s (1894) edition and the apparatus fontium in Meyer’s (1909) German translation of Theodore’s work passim.

- On Cassius Felix and his work, see Fraisse (2002: vii–xxviii). See also Langslow (2000: 56–60).

- On the abundant use of Greek terminology in Cassius’ work, see Fraisse (2002: lvii–lxi).

- Cassius Felix, On Medicine, 18.5 and 20.2, ed. Fraisse (2002) 34.3 and 37.5.

- See, for example, Cassius Felix, On Medicine, 71.6, ed. Fraisse (2002) 192.13–17.

- Cassius Felix, On Medicine, pr., ed. Fraisse (2002) 4.2–5.

- Fraisse (2002: xxix–xxx); and Temkin (1977: 175).

- See Fraisse (2002: xxx–xxxi).

- Fraisse (2002: xv, xxxii–xxxv).

- Nutton (1984: 2).

- This has also been recently pointed out by van der Eijk et al. (2015: 215).

- On this, see Bouras-Vallianatos (Chapter 4) in this volume.

Bibliography

- Baader, G. 1984. ‘Early Medieval Latin Adaptations of Byzantine Medicine in Western Europe’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 38: 251–9.

- Boudon, V. (ed). 2000. Galien, Tome II.Exhortation à l’ étude de la médecine. Art médical. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

- Boudon-Millot, V. 2014. ‘Le divin Hippocrate de Galien’, in J. Jouanna and M. Zink (eds.), Hippocrate et les hippocratismes: Médecine, religion, société. Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres, 253–69.

- Bouras-Vallianatos, P. 2014. ‘Clinical Experience in Late Antiquity: Alexander of Tralles and the Therapy of Epilepsy’, Medical History 58: 337–53.

- Bouras-Vallianatos, P. 2016. ‘Modelled on Archigenes theiotatos: Alexander of Tralles and his Use of Natural Remedies (physika)’, Mnemosyne 69: 382–96.

- Bouras-Vallianatos, P. 2018. ‘Reading Galen in Byzantium: The Fate of Therapeutics to Glaucon’, in P. Bouras-Vallianatos and S. Xenophontos (eds.), Greek Medical Literature and its Readers: From Hippocrates to Islam and Byzantium. New York: Routledge, 180–229.

- Bravos, S. 1974. ‘Das Werk des Aetios v. Amida und seine medizinischen und nicht-medizinischen Quellen’. Diss., University of Hamburg.

- Buzzi, S. and F. Messina. 2014. ‘The Latin and Greek Tradition of the Corpus Oribasianum’, in B. Maire (ed.), ‘Greek’ and ‘Roman’ in Latin Medical Texts: Studies in Cultural Change and Exchange in Ancient Medicine. Leiden: Brill, 289–314.

- Calà, I. 2012a. ‘Per l’edizione del primo dei Libri medicinales di Aezio Amideno’. PhD diss., University of Bologna.

- Calà, I. 2012b. ‘Il medico Andreas nei Libri medicinales di Aezio Amideno’, Galenos 6: 53–64.

- Calà, I. 2016a. ‘Terapie tra magia e religion. La gravidanza e il parto nei testi medici della Tarda Antichità’, in M. T. Santamaría Hernández (ed.), Traducción y transmisión doctrinal de la Medicina grecolatina desde la Antigüedad hasta el Mundo Moderno: nuevas aportaciones sobre autores y textos. Cuenca: Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, 11–24.

- Calà, I. 2016b. ‘The Therapeutic Use of Mineral Amulets in Medical Works of Late Antiquity’, Pegasus 59: 23–9.

- Capone Ciollaro, M. and I. G. Galli Calderini. 1992. ‘Problemi relativi alle fonti di Aezio Amideno nei libri IX–XVI: Galeno e Oribasio’, in A. Garzya (ed.), Tradizione e ec-dotica dei testi medici tardoantichi e bizantini. Naples: D’Auria, 51–72.

- Debru, A. 1992. ‘La suffocation hystérique chez Galien et Aetius. Réécriture et emprunt du “je”’, in A. Garzya (ed.), Tradizione e ecdotica dei testi medici tardoantichi e bizantini. Naples: D’Auria, 79–89.

- Doody, A. 2009. ‘Authorial Voice in the Medicina Plinii’, in L. Taub and A. Doody (eds.), Authorial Voices in Greco-Roman Technical Writing. Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, 93–105.

- Dubischar, M. 2016. ‘Preserved Knowledge: Summaries and Compilations’, in M. Hose and D. Schenker (eds.), A Companion to Greek Literature. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 427–40.

- Eijk, P. van der. 1999. ‘Antiquarianism and Criticism: Forms and Functions of Medical Doxography in Methodism (Soranus, Caelius Aurelianus)’, in P. van der Eijk (ed.), Ancient Histories of Medicine: Essays in Medical Doxography and Historiography in Classical Antiquity. Leiden: Brill, 397–452.

- Eijk, P. van der. 2010. ‘Principles and Practices of Compilation and Abbreviation in the Medical “Encyclopaedias” of Late Antiquity’, in M. Horster and C. Reitz (eds.), Condensing Text – Condensed Texts. Stuttgart: Steiner, 519–54.

- Eijk, P. van der, Geller, M., Lehmhaus, L., Martelli, M. and C. Salazar. 2015. ‘Canons, Authorities and Medical Practice in the Greek Medical Encyclopaedias of Late Antiquity and in the Talmud’, in E. Cancik-Kirschbaum and A. Traninger (eds.), Wissen in Bewegung: Institution – Iteration – Transfer. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 195–221.

- Fischer, K.-D. 2012. ‘Die spätlateinische Übersetzung von Galen, ad Glauconem (Kühn XI 1–146)’, Galenos 6: 103–16.

- Fischer, K.-D. 2013. ‘Die vorsalernitanischen lateinischen Galenübersetzungen’, Medicina nei Secoli 25: 673–714.

- Flemming, R. 2007. ‘Women, Writing and Medicine in the Classical World’, Classical Quarterly 57: 257–79.

- Formisano, M. 2001. Tecnica e scrittura: le letterature tecnico-scientifiche nello spazio letterario tardolatino. Rome: Carocci.

- Formisano, M. 2004. ‘The “Natural” Medicine of Theodorus Priscianus: Between Tradition and Innovatios’, Philologus 148: 126–42.

- Fraisse, A. (ed.). 2002. Cassius Felix. De la médecine. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

- Fraisse, A. 2003. ‘Médecine rationnelle et irrationnelle dans le livre I des Euporista de Théodore Priscien’, in N. Palmieri (ed.), Rationnel et irrationnel dans la médecine ancienne et médiévale: aspects historiques, scientifiques et culturels. Saint-Étienne: Publications de l’Université de Saint-Étienne, 183–92.

- Garzya, A. 1984. ‘Problèmes relatifs à l’édition des livres IX–XVI du Tétrabiblon d’Aétios d’Amida’, Revue des Études Anciennes 86: 245–57.

- Guardasole, A. 2004a. ‘Alexandre de Tralles et les remèdes naturels’, in F. Collard and E. Samama (eds.), Mires, physiciens, barbiers et charlatans: les marges de la médicine de l’Antiquité au XVIe siècle. Langres: D. Gueniot, 81–99.

- Guardasole, A. 2004b. ‘L’héritage de Galien dans l’oeuvre d’Alexandre de Tralles’, in J. Jouanna and J. Leclant (eds.), Colloque La médecine grecque antique, Cahiers de la Villa ‘Kérylos’. Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres, 211–26.

- Guardasole, A. 2006. ‘Alessandro di Tralle’, in A. Garzya et al. (eds.), Medici Bizantini. Turin: Unione Tipografico-Editrice Torinese, 557–786.

- Heiberg, J. L. (ed.). 1921–4. Paulus Aegineta. 2 vols. Leipzig: Teubner.

- Henry, R. (ed.). 1959–91. Photius: Bibliothèque. 9 vols. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

- Hunger, H. 1978. Die hochsprachliche profane Literatur der Byzantiner. 2 vols. Munich: Beck.

- Jouanna, J. 2011. ‘Médecine rationnelle et magie: le statut des amulettes et des incanta-tions chez Galien’, Revue des Études Grecques 124: 47–77.

- Jones, W. H. S. (ed.). 1931. Hippocrates, vol. IV. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- König, J. 2005. Athletics and Literature in the Roman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kudlien, F. 1965. ‘Zum Thema “Homer und die Medizin”’, Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 108: 293–9.

- Kühn, C. G. (ed.). 1821–33. Claudii Galeni opera omnia. 20 vols. in 22. Leipzig: Knobloch.

- Langslow, D. 2000. Medical Latin in the Roman Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Langslow, D. 2006. The Latin Alexander Trallianus. London: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies.

- Leven, K.-H. 2005. (ed.). Antike Medizin: ein Lexikon. Munich: Beck.

- Littré, É. (ed.). 1839–61. Oeuvres complètes d’Hippocrate: traduction nouvelle avec le textegrec en regard, collationné sur les manuscrits et toutes les éditions; accompagnée d’une introduction, de commentaires médicaux, de variantes et de notes philologiques; suivie d’une table générale des matières. 10 vols. Paris: J.-B. Baillière.

- Luchner, K. 2004. Philiatroi: Studien zum Thema der Krankheit in der griechischen Literatur der Kaiserzeit. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Lucia, R. de. 1996. ‘Esempi di tecnica compositiva e utilizzazione delle fonti nei Libri medicinales di Aezio Amideno’, in F. Conca (ed.), Byzantina Mediolanensia: Atti del V Congresso Nazionale di Studi Bizantini (Milano, 19–22 ottobre 1994). Soveria Mannelli: Rubbettino, 143–53.

- Lucia, R. de. 1999a. ‘Doxographical Hints in Oribasius’ Collectiones Medicae’, in P. van der Eijk (ed.), Ancient Histories of Medicine: Essays in Medical Doxography and Historiography in Classical Antiquity. Leiden: Brill, 473–89.

- Lucia, R. de. 1999b. ‘Terapie ippocratiche in Oribasio e Aezio Amideno: l’eredità di Ippocrate nelle enciclopedie mediche fra tardoantico e protobizantino’, in I. Garofalo et al. (eds.), Aspetti della terapia nel Corpus Hippocraticum. Florence: L. S. Olschki, 447–45.

- Lucia, R. de. 2006. ‘Oribasio di Pergamo’, in A. Garzya et al. (eds.), Medici Bizantini. Turin: Unione Tipografico-Editrice Torinese, 20–251.

- MacLachlan, R. 2006. ‘Epitomes in Ancient Literary Culture’. PhD diss., University of Cambridge.

- Marganne, M.-H. 2010. ‘La “bibliothèque médicale” de Photios’, Medicina nei Secoli 22: 509–30.

- Marquardt, I. (ed.). 1884. Claudii Galeni Pergameni Scripta Minora, recensuerunt I. Marquardt, I. Mueller, G. Helmreich, vol. I. Leipzig: Teubner.

- Mercati, G. 1917. ‘Un nuovo capitolo di Sorano e tre nuove ricette superstiziose in Aezio’, Studi e Testi 31: 42–66.

- Meyer, T. (tr.). 1909. Theodorus Priscianus und die römische Medizin. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

- Migliorini, P. 1991. ‘Elementi metodici in Teodoro Prisciano’, in P. Mudry and J. Pigeaud (eds.), Les écoles médicales à Rome. Geneva: Droz, 231–40.

- Nutton, V. 1984. ‘From Galen to Alexander: Aspects of Medicine and Medical Practice in Late Antiquity’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 38: 1–14.

- Olivieri, A. (ed.). 1935–50. Aetii Amideni Libri medicinales. 2 vols. Leipzig: Teubner.

- Önnerfors, A. 1993. ‘Das medizinische Latein von Celsus bis Cassius Felix’, Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen WeltII, 37.I: 227–392.

- Overwien, O. 2018. ‘Der medizinische Unterricht der Iatrosophisten in der “Schule von Alexandria” (5.‒7. Jh. n. Chr.): Überlegungen zu seiner Organisation, seinen Inhalten und seinen Ursprüngen’, Philologus (erster Teil) 162(1): 2–14; (zweiter Teil) 162(2): 265–90.

- Palmieri, N. 2001. ‘Nouvelles remarques sur les commentaires à Galien de l’école médicale de Ravenne’, in A. Debru and N. Palmieri (eds.), Docente Natura. Mélanges de Médecine ancienne et médiévale offerts à Guy Sabbah. Saint-Étienne: Publications de l’Université de Saint-Étienne, 209–46.

- Petit, C. 2013. ‘The Fate of a Greek Medical Handbook in the Medieval West: The Introduction, or the Physician ascribed to Galen’, in B. Zipser (ed), Medical Books in the Byzantine World. Bologna: Eikasmos, 57–77.

- Pormann, P. E. 2004. The Oriental Tradition of Paul of Aegina’s Pragmateia. Leiden: Brill.

- Puschmann, T. (ed.). 1878–9. Alexander von Tralles. 2 vols. Vienna: W. Braumüller.

- Raeder, H. (ed.). 1926. Oribasii Synopsis ad Eustathium, Libri ad Eunapium. Leipzig: Teubner.

- Raeder, H. (ed.). 1928–33. Oribasii Collectionum medicarum reliquiae. 2 vols. in 4. Leipzig: Teubner.

- Rocca, J. 2012. ‘Methodism’, in S. R. Bagnall et al. (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah21213/full (accessed 10 February 2017).

- Romano, R. 2006. ‘Aezio Amideno libro XVI’, in A. Garzya (ed.), Medici Bizantini. Turin: Unione Tipografico-Editrice Torinese, 251–553.

- Rose, V. (ed.). 1894. Theodori Prisciani Euporiston libri III. Leipzig: Teubner.

- Scarborough, J. 1984. ‘Early Byzantine Pharmacology’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 38: 213–32.

- Scarborough, J. 2013. ‘Theodora, Aetius of Amida, and Procopius: Some Possible Connections’, Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 53: 742–62.

- Sideras, A. 1974. ‘Aetius und Oribasius. Ihre gemeinsamen Exzerpte aus der Schrift des Rufus von Ephesos “Über die Nieren- und Blasenleiden” und ihr Abhängigkeitsverhältnis’, Byzantinische Zeitschrift 47: 110–30.

- Stok, F. 2008. ‘Marcellus of Bordeaux, “Empiricus”’, in P. Keyser and G. Irby-Massie (eds.), Encyclopedia of Ancient Natural Scientists. Abingdon: Routledge, 527–30.

- Tabanelli, M. 1964. Studi sulla chirurgia bizantina. Paolo di Egina. Florence: Leo S. Olschki Editore.

- Temkin, O. 1973. Galenism: Rise and Decline of a Medical Philosophy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Temkin, O. 1977. ‘History of Hippocratism in Late Antiquity: The Third Century and the Latin West’, in O. Temkin, The Double Face of Janus and Other Essays in The History of Medicine. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 167–77. [Originally published in German: ‘Geschichte des Hippokratismus im ausgehenden Altertum’, Kyklos 4 (1932): 18–28.]

- Urso, A. M. 1996. Dall’autore al traduttore: studi sulle Passiones celeres e tardae di Celio Aureliano. Messina: EDAS.

- Xenophontos, S. 2018. ‘Galen’s Exhortation to the Study of Medicine: An Educational Work for Prospective Medical Students’, in P. Bouras-Vallianatos and S. Xenophontos (eds.), Greek Medical Literature and its Readers: From Hippocrates to Islam and Byzantium. Abingdon: Routledge, 67–93.

Chapter 2 (38-61) from Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Galen, by Petros Bouras-Vallianatos (Brill, 03.21.2019), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.