From papyrus to AI, the history of restricted access to technology reveals a consistent interplay of innovation and control.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Throughout history, the emergence of new technologies has rarely been accompanied by unrestricted diffusion. From the earliest writing systems to the most advanced artificial intelligence, societies have recognized that knowledge is inseparable from power, and power is seldom shared freely. Technological innovation, while capable of transforming economies, militaries, and cultures, has often been deliberately guarded, its circulation restricted by elites, states, guilds, or corporations. Such acts of limitation reveal as much about the nature of authority as the technologies themselves.

This essay traces the history of restricted access to technologies across four broad eras: the ancient world, the medieval and early modern period, the Enlightenment and Industrial age, and the modern and contemporary world. Each epoch offers case studies in which access to new tools (whether papyrus, Greek fire, silk, printing presses, navigational charts, or nuclear codes) was bound up in the politics of control. Examining these examples reveals a recurrent historical logic: technologies with the potential to disrupt existing hierarchies are most often confined to the very circles they might otherwise destabilize.

Far from being accidental episodes of secrecy, these restrictions form a continuous thread in human history, underscoring how the distribution of knowledge has been at least as important as its creation. To understand the story of technological progress, then, is also to understand the equally persistent story of technological restriction.

Ancient World

Egyptian Papyrus and Writing Systems

In ancient Egypt, the ability to write was not a democratized skill but a guarded technology of power. Literacy resided largely within the closed circles of priestly and bureaucratic scribes. Papyrus, the medium upon which state decrees, sacred texts, and economic records were inscribed, was itself a controlled commodity.1 Its production centered in royal workshops, and its circulation was shaped by state oversight. By limiting access to both the skill of writing and the material upon which it was performed, the pharaonic state ensured that the machinery of record and law remained in the hands of a narrow elite. Writing thus functioned as an instrument of political sovereignty, binding memory and authority together.

Greek Fire (Byzantine Empire)

Among the most jealously guarded military technologies in history was the Byzantine weapon known as Greek fire. Introduced in the seventh century, it transformed naval warfare through its capacity to ignite even upon water.2 The formula was kept secret within imperial circles, entrusted to select artisans bound by oaths of silence. So effective was this restriction that the chemical composition has eluded historians to the present day. In this instance, secrecy created both strategic advantage and cultural mystique, embedding technology within a theology of imperial favor, a divine gift to Constantinople.

Chinese Silk Production

Equally legendary was the Chinese state’s control of sericulture. For centuries, silk production was the cornerstone of imperial wealth and global trade. Smuggling silkworms or eggs was punishable by death.3 In restricting both knowledge of silk cultivation and access to its raw materials, China preserved its monopoly until the mid-first millennium, when Byzantine envoys succeeded in obtaining silkworms clandestinely. Here, the regulation of technology intersected with geopolitics, shaping the very arteries of the Silk Road economy.

Medieval and Early Modern

Guild Restrictions in Europe

In medieval Europe, guilds functioned as both professional associations and knowledge vaults. The mason’s lodge, the blacksmith’s forge, the glassmaker’s furnace; all were sites where technical skills were transmitted only through lengthy apprenticeships, sealed by oaths of secrecy.4 A guild’s monopoly over its craft created a barrier to entry that safeguarded the livelihoods of its members while restricting innovation to a closed circle. In the art of stained glass, for example, formulas for producing particular hues, such as the deep cobalt blues of Gothic cathedrals, were guarded as fiercely as treasures.

Printing Press Censorship

The arrival of Gutenberg’s press in the fifteenth century inaugurated not only a revolution in communication but also a struggle over restriction. Monarchs and church authorities quickly moved to regulate the new technology through licensing, censorship, and legal monopolies.5 In England, the Stationers’ Company became the mechanism by which the crown ensured that presses remained aligned with state and ecclesiastical authority. By attempting to control the press, rulers sought to domesticate what was otherwise a democratizing force, the sudden mass accessibility of text.

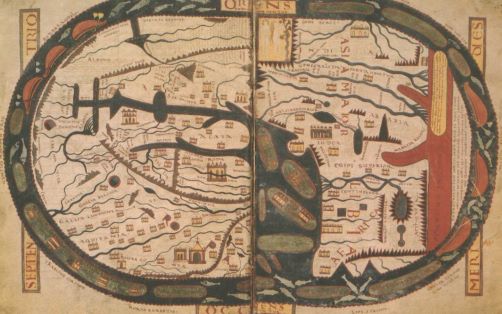

Navigation and Cartography

In the early modern period, the control of geographical knowledge became essential to imperial competition. Spain and Portugal, spearheading the maritime expansions of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, treated nautical charts as state secrets.6 Pilots were often sworn not to share them, and cartographers faced harsh penalties for divulging discoveries. Maps thus became weapons of empire, not simply instruments of navigation. Restricting their access was tantamount to restricting the imagination of conquest itself.

Enlightenment and Industrial Era

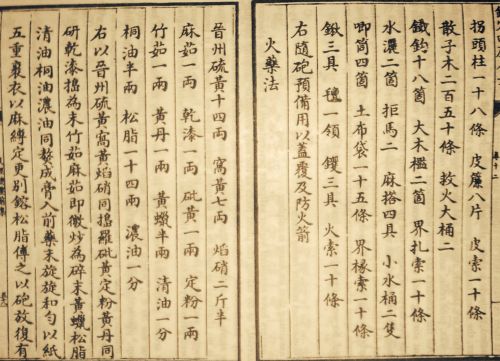

Gunpowder and Firearms

Gunpowder technologies, first transmitted from China to the Islamic world and then to Europe, illustrate how rulers recognized the danger of technological diffusion. States often restricted firearm manufacture to arsenals under royal control.7 In both Ming China and early modern Europe, guilds or royal foundries became exclusive sites of production. By limiting access, rulers preserved their military dominance and forestalled the empowerment of insurgent groups.

Industrial Machines

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Britain’s dominance in industrial manufacturing rested not only on technological invention but also on deliberate restriction. Laws prohibited the export of key textile machinery and forbade skilled mechanics from emigrating.8 Only through espionage and the smuggling of designs did the secrets of mechanized spinning and weaving reach continental Europe and the United States. Britain’s effort to monopolize the machinery of modern industry mirrored earlier imperialisms of knowledge, but on a new, mechanized scale.

Medical Knowledge

Medical knowledge, too, was often confined within professional hierarchies. Anatomical discoveries emerging from Renaissance dissections were mediated by universities that restricted admission and, more significantly, barred women from participation.9 The control of surgical knowledge by professional guilds and colleges ensured that healing arts remained both a livelihood and a privilege. Restricting access served less the progress of science than the consolidation of professional authority.

Modern and Contemporary

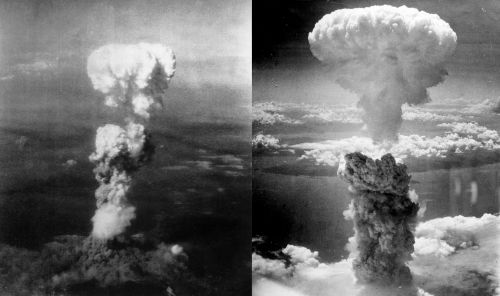

Nuclear Technology

The twentieth century’s atomic age epitomized the restricted technology par excellence. The Manhattan Project operated in secrecy, with even close allies often excluded from sensitive details.10 After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nuclear knowledge became the fulcrum of Cold War geopolitics. Export controls, espionage trials, and international treaties all sought to regulate who could hold the keys to atomic fire. In this case, secrecy was framed not as economic advantage but as existential necessity.

Encryption and Computing

As digital technologies emerged, the U.S. government treated cryptography as a matter of national security, classifying strong encryption as a form of munition.11 Export restrictions in the late twentieth century made the possession and dissemination of certain software a potential felony. Here again, the logic of restriction lay in the balance between state surveillance and individual privacy, a contest that continues into the present.

Pharmaceutical Patents

The corporate world has also wielded the power of restriction. The pharmaceutical industry’s use of patent law has limited access to lifesaving medicines, most notoriously during the HIV/AIDS crisis of the 1990s.12 Patents kept drug prices high and distribution limited in the Global South, even as millions died. Only sustained global activism forced partial openings. The restriction of medical technology, once a matter of professional guilds, has thus been reborn in the register of intellectual property law.

Artificial Intelligence

In the early twenty-first century, artificial intelligence marks the newest frontier of technological restriction. State export controls, corporate licensing, and non-disclosure agreements keep the most powerful models in the hands of a few entities.13 Like silk, gunpowder, and nuclear fire before it, AI becomes a technology bound by secrecy and guarded gates. The pattern is clear: wherever technology holds the potential to redistribute power, those already in possession of power restrict its flow.

Conclusion

From papyrus to AI, the history of restricted access to technology reveals a consistent interplay of innovation and control. Each instance demonstrates that the dissemination of new tools is never a neutral process. It is shaped by states, guilds, churches, corporations, and empires, institutions that perceive in every new invention both opportunity and threat. What unites these stories is not merely the guarding of formulas or machines but the recognition that knowledge itself is the most dangerous weapon, capable of unsettling hierarchies. Restriction, then, is not an accident of history but one of its driving logics.

Appendix

Footnotes

- John Baines and Christopher Eyre, Visual & Written Culture in Ancient Egypt (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 75–80.

- John Haldon, Byzantine Praetorians: An Administrative, Institutional and Social Survey of the Opsikion and Tagmata, c. 580–900 (Bonn: Rudolf Habelt, 1984), 223–227.

- Valerie Hansen, The Silk Road: A New History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 44–46.

- Steven Epstein, Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 92–96.

- Elizabeth Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 184–188.

- Felipe Fernández-Armesto, Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 142–145.

- Bert S. Hall, Weapons and Warfare in Renaissance Europe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 57–60.

- Jenny Uglow, The Lunar Men: The Friends Who Made the Future (London: Faber & Faber, 2002), 276–280.

- Katharine Park, Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection (New York: Zone Books, 2010), 112–118.

- Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986), 503–509.

- Bruce Schneier, Applied Cryptography (New York: Wiley, 1993), 24–27.

- Peter J. Hotez, Forgotten People, Forgotten Diseases (Washington, DC: ASM Press, 2008), 190–193.

- Kate Crawford, Atlas of AI (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021), 33–36.

Bibliography

- Baines, John. Visual & Written Culture in Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Crawford, Kate. Atlas of AI. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021.

- Eisenstein, Elizabeth. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

- Epstein, Steven. Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

- Fernández-Armesto, Felipe. Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Hall, Bert S. Weapons and Warfare in Renaissance Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

- Haldon, John. Byzantine Praetorians: An Administrative, Institutional and Social Survey of the Opsikion and Tagmata, c. 580–900. Bonn: Rudolf Habelt, 1984.

- Hansen, Valerie. The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Hotez, Peter J. Forgotten People, Forgotten Diseases. Washington, DC: ASM Press, 2008.

- Park, Katharine. Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection. New York: Zone Books, 2010.

- Rhodes, Richard. The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986.

- Schneier, Bruce. Applied Cryptography. New York: Wiley, 1993.

- Uglow, Jenny. The Lunar Men: The Friends Who Made the Future. London: Faber & Faber, 2002.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.22.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.