By equating political opposition with existential threat, leaders constructed a framework in which violence became inevitable. The guillotine was the logical conclusion of words that demanded purification.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

“When every political opponent becomes an enemy of the nation, violence stops being an aberration and starts being policy.”

That insight captures the dark trajectory of the French Revolution, when ideals of liberty and fraternity dissolved into the blood of political purges. The Revolution’s political vocabulary did more than describe enemies; it created them.

What follows examines how the rhetoric of “traitors,” “enemies of the people,” and “purification” in revolutionary France fostered conditions in which the guillotine became an instrument of legitimacy. Such language did not remain confined to speeches or pamphlets. It shaped the emotional climate of the era, framing violence as necessary, just, and even sacred.

Revolutionary Rhetoric and the Making of Enemies

The Revolution was born in 1789 with declarations of rights and appeals to universal equality, yet from the earliest days, its discourse bore the seeds of division. Jacobin leaders like Maximilien Robespierre spoke of “virtue” as inseparable from terror, declaring that “virtue without terror is powerless.”1 In this formulation, terror became not a departure from revolutionary ideals but their guardian.

Language recast political disagreements as existential threats. Royalists were not framed as opponents to be debated but as conspirators in league with foreign powers. Priests who refused the Civil Constitution of the Clergy were not dissenters but enemies of liberty.2 By attaching the word “enemy” to internal adversaries, revolutionary rhetoric denied them political legitimacy.

The categories expanded with alarming speed. By 1793, moderates, Girondins, and even once-trusted allies could be branded as traitors. The elasticity of these labels ensured that no one could be fully safe, for the Revolution required enemies to sustain its fervor.

Purification and the Imaginary of Cleansing

The metaphor of purification coursed through revolutionary texts and speeches. Enemies were described as a disease in the body politic, a contagion that could only be cut away.3 Such metaphors drew upon a long history of medical and religious imagery, where purgation and sacrifice were seen as the path to renewal.

The guillotine, introduced in 1792, was celebrated as both humane and symbolic. It was not simply a method of execution; it was a stage for public pedagogy. Crowds gathered not only to witness justice but to participate in a ritual of cleansing. Each head that fell was meant to purge corruption and reaffirm the Revolution’s purity.

This rhetoric allowed violence to be reframed as civic duty. To tolerate “enemies of the people” was to betray the collective. To eliminate them was to serve the general will. Once that frame hardened, compromise became indistinguishable from treason.

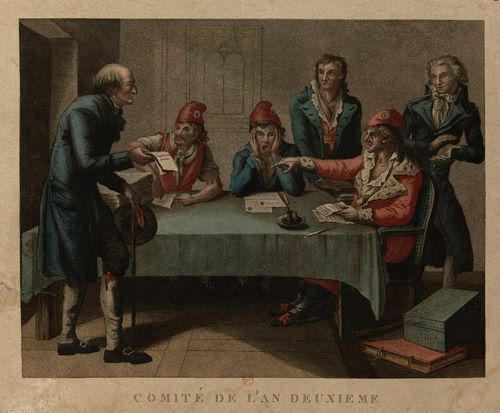

The Reign of Terror: Words Becoming Flesh

By the summer of 1793, the Revolution had entered what historians call the Reign of Terror. The language of enemies now justified mass trials and rapid executions. Revolutionary tribunals processed accusations with ruthless efficiency, their verdicts already inscribed in the rhetoric of the time.

Robespierre himself argued that terror was “prompt, severe, inflexible justice.”4 The very phrasing collapsed law into violence, and procedure into spectacle. The guillotine became the endpoint of speeches delivered in the National Convention, the final punctuation to debates framed not as disputes among citizens but as battles between the virtuous and the damned.

The Terror claimed thousands of lives in Paris and the provinces. Many were not aristocrats or priests but ordinary citizens accused of hoarding, dissent, or insufficient enthusiasm. The language that had once targeted the monarchy now devoured the Revolution’s own children.

The Dialectic of Fear and Belonging

The rhetoric of enemies did not only instill fear; it also generated belonging. To declare loyalty to the Revolution was to distinguish oneself from traitors. To shout approval during trials or to attend public executions was to perform fidelity to the nation. Silence could be read as complicity, hesitation as treachery.

Fear and participation thus reinforced one another. The people’s presence at executions gave legitimacy to the process, while the state’s insistence on enemies gave coherence to the people. In this dialectic, political violence was not a breakdown of order but the very mechanism of revolutionary order.

Historical Echoes and Modern Parallels

The French Revolution demonstrates how rhetoric can shift the boundaries of the permissible. By equating political opposition with existential threat, leaders constructed a framework in which violence became inevitable. The guillotine was not the product of abstract cruelty but the logical conclusion of words that demanded purification.

Modern parallels are not difficult to discern. Movements across the political spectrum have employed similar languages of treason and contamination. When opponents are branded “enemies of the people,” when compromise is cast as betrayal, the stage is set for extraordinary measures. The Revolution reminds us that once rhetoric transforms adversaries into existential foes, violence is not a possibility but a prescription.

Conclusion

The French Revolution’s trajectory from rights to terror illustrates the peril of political discourse that collapses opposition into enmity. The language of “traitors,” “enemies,” and “purification” did not merely accompany the violence of the 1790s; it structured and legitimized it.

When words become weapons, they create realities in which compromise is weakness and violence is justice. That lesson, written in blood on the scaffold of the guillotine, remains urgent for any society that prizes liberty but toys with rhetoric of exclusion and fear.

Appendix

Notes

- Maximilien Robespierre, speech to the National Convention, February 1794, in Œuvres complètes de Robespierre (Paris: Société des études robespierristes, 1910).

- Timothy Tackett, Religion, Revolution, and Regional Culture in Eighteenth-Century France (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986).

- Lynn Hunt, Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984).

- Robespierre, speech to the Convention, September 1793, in Œuvres complètes de Robespierre.

Bibliography

- Hunt, Lynn. Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

- Robespierre, Maximilien. Œuvres complètes de Robespierre. Paris: Société des études robespierristes, 1910.

- Tackett, Timothy. Religion, Revolution, and Regional Culture in Eighteenth-Century France. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.15.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.