From Rome’s public boards to Egypt’s buried jars, from ostraka to forbidden books, lists were instruments of power. They condemned, they concealed, they excluded, they preserved.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

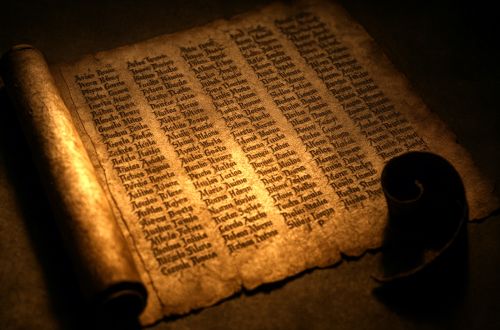

The idea of a “list” carries a peculiar dread. In the modern world, rumors swirl about shadowy ledgers that supposedly expose the guilty or the powerful, names whispered but not confirmed, sparking both suspicion and fascination. Few symbols capture secrecy more effectively than the roster of names that is said to exist but rarely revealed. Ancient societies were no strangers to this dynamic. From Rome to Egypt, from Athens to early Christianity, lists served as instruments of inclusion and exclusion, of memory and erasure, of public spectacle and hidden terror.

The ancients understood that writing a name could alter fate. A name carved into stone or inked on a scroll was more than a label. It became a sentence, a stigma, or a sacred secret. By tracing how different cultures constructed and concealed their lists, we can see the enduring human urge to bind power to inscription.

The Roman Proscriptions

When Sulla marched into Rome and seized power in 82 BCE, he ruled not only with soldiers but with names. The infamous proscription lists transformed political victory into bureaucratic death warrants.1 To see a name posted in the Forum was to witness the machinery of annihilation at work.

The proscriptions were economic as much as political. Property of the condemned was confiscated, enriching both the state and opportunistic allies.2 This allowed the lists to expand far beyond Sulla’s enemies. Old rivals, creditors, even inconvenient relatives might suddenly find themselves declared hostes, their names plastered on the wall for all to see.

For ordinary Romans, the lists reshaped civic life. Daily routines carried the background hum of fear, as passersby scanned the Forum’s boards wondering whose name might appear next. The spectacle reminded everyone that power could inscribe itself onto paper and turn ink into blood.

The Second Triumvirate, decades later, revived the tactic with greater ferocity. Cicero’s inclusion remains the most notorious case.3 His murder and mutilation, hands and head nailed to the rostra, turned the lists into a theater of revenge. Roman politics was reordered through the posting of names, demonstrating that survival depended less on loyalty than on whether one’s name escaped inscription.

Athenian Ostracism and the Politics of Names

Athens’ ostracism seems at first to offer a gentler contrast: exile rather than execution. Citizens scrawled names onto pottery shards, the ostraka, which were counted to determine who must leave the city for a decade.4 Yet the ritual carried its own kind of menace.

The secrecy of the vote gave ostracism its democratic sheen, but behind the anonymity lay manipulation. Archaeologists have uncovered caches of ostraka where the same hand wrote dozens of names.5 Factions prepared stacks of pre-inscribed shards, distributing them to voters. What appeared as individual judgment was often a coordinated act of exclusion.

The stories of Themistocles and Aristides illustrate the system’s ambiguity. One, celebrated as a savior against Persia, fell into suspicion; the other, admired for integrity, was cast out simply because citizens grew weary of his reputation.6 Their names, once marks of esteem, became inscriptions of rejection.

Athens’ lists did not kill, but they unsettled. To be written onto a shard was to be rendered absent, one’s presence deemed too dangerous for the city. The ritual dramatized democracy’s shadow: collective power could erase individuals in silence, with only shards of pottery left to tell the tale.

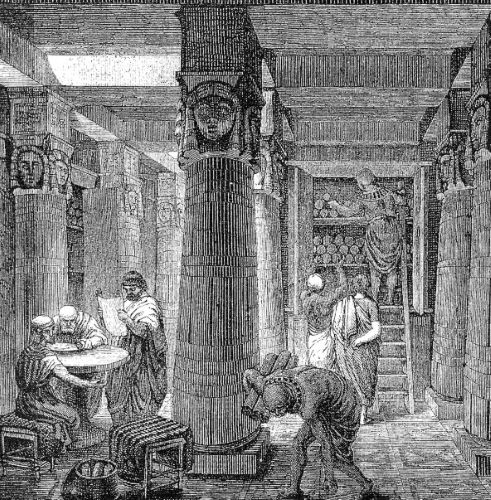

Hidden Catalogues of Alexandria

The Library of Alexandria promised universal knowledge, yet even within its marble halls, secrecy thrived. Alongside its celebrated collections, royal catalogues indexed works deemed too dangerous or arcane for circulation.7 These lists were not displayed but hidden, whispering of texts that existed yet could not be seen.

Philosophical treatises on mechanics, magical rites, and speculative cosmology were said to be locked away. Later writers suggested that these forbidden texts carried explosive potential, whether by revealing natural secrets or challenging political authority.8 Their very concealment amplified their power.

Unlike Rome’s lists of death or Athens’ rosters of exile, the Alexandrian index preserved rather than destroyed. To appear in the catalogue was to be protected from the world, but also denied to it. For scholars aware of their existence, the secret books became tantalizing ghosts, reminders that knowledge itself could be proscribed.

Egyptian Execration Lists

Egypt’s execration texts reveal a different logic. Pharaohs ordered names of enemies inscribed on clay figurines or jars, which were then ritually smashed and buried.9 To write a name was to bind its bearer in curse, condemning them to destruction in both the physical and spiritual realms.

The power of these lists lay in secrecy. Unlike Rome’s public boards, execration texts were hidden underground. Their concealment magnified their potency. A general, a tribe, or a rebellious prince might never know that their name had been written, yet still suffer its magical weight.10

For modern eyes, the practice appears symbolic, but to Egyptians it was both practical and divine. The ritual enacted Pharaoh’s cosmic role as protector. By shattering the figurines, enemies were broken in effigy and in destiny. The lists did not merely record; they enacted.

Archaeological discoveries of these fragments underscore their prevalence. Each buried cache was a silent archive of political fear, where clay bore the burden of imperial anxiety. Egypt’s lists remind us that secrecy itself can be a weapon. Names destroyed in darkness haunt just as powerfully as those displayed in daylight.

Early Christian Heresiological Lists

As Christianity expanded, it faced the problem of boundaries. Bishops and councils responded by naming the transgressors. Early catalogues of heretics listed Valentinus, Marcion, Montanus, and others, branding them as enemies of the faith.11 These names circulated in treatises and synodal reports, creating a roster of the damned.

What is striking is how often the names outlived the movements. Many of the sects dwindled into obscurity, but the lists kept their memory alive.12 To be inscribed as heretical was to achieve a grim immortality, a permanent mark of exclusion.

In time, these scattered catalogues hardened into institutions. The Index Librorum Prohibitorum, centuries later, grew out of the same impulse to name and forbid. Orthodoxy defined itself by inscription, building its walls not only through theology but through lists.

The Christian heresiological tradition thus linked salvation to memory and damnation to inscription. The act of writing a name, whether onto papyrus or into ecclesiastical record, bound identity forever.

Conclusion: The Allure and Terror of the Hidden List

From Rome’s public boards to Egypt’s buried jars, from ostraka to forbidden books, lists were instruments of power. They condemned, they concealed, they excluded, they preserved. Across civilizations, the simple act of inscription turned names into fates.

The fascination persists because lists hover between revelation and secrecy. Some, like the Roman proscriptions, terrify by exposure. Others, like Egyptian execrations or Alexandrian catalogues, unsettle by concealment. In every case, the aura of the list exceeds the names it contains.

Modern society inherits this tension. Whispered rosters of scandal or crime continue to grip public imagination, not only for who might be on them but for the fact that they exist at all. To name is to control. To be named is to be bound. The ancients knew it well, and their shadows still fall across our headlines.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Cicero, Philippics, trans. D. R. Shackleton Bailey (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), 13.

- Harriet I. Flower, Roman Republics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), 97–99.

- Ibid., 112; Cicero, Philippics, 23.

- Sara Forsdyke, Exile, Ostracism, and Democracy: The Politics of Expulsion in Ancient Greece (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 54–56.

- Forsdyke, Exile, Ostracism, and Democracy, 78–81.

- Plutarch, Lives, Volume II: Themistocles and Camillus, trans. Bernadotte Perrin (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1914), 65–66.

- Christopher Haas, Alexandria in Late Antiquity: Topography and Social Conflict (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 121–123.

- Haas, Alexandria in Late Antiquity, 134–36.

- Ogden Goelet, “Execration Texts of Ancient Egypt,” in The Literature of Ancient Egypt, ed. William Kelly Simpson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972), 353–371.

- Ibid., 368.

- Irenaeus, Against Heresies, trans. Dominic J. Unger (New York: Paulist Press, 1992), 19–22.

- Ibid., 45–47.

Bibliography

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. Philippics. Translated by D. R. Shackleton Bailey. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Flower, Harriet I. Roman Republics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

- Forsdyke, Sara. Exile, Ostracism, and Democracy: The Politics of Expulsion in Ancient Greece. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Goelet, Ogden. “Execration Texts of Ancient Egypt.” In The Literature of Ancient Egypt, edited by William Kelly Simpson, 353–371. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972.

- Haas, Christopher. Alexandria in Late Antiquity: Topography and Social Conflict. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

- Irenaeus. Against Heresies. Translated by Dominic J. Unger. New York: Paulist Press, 1992.

- Plutarch. Lives, Volume II: Themistocles and Camillus. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1914.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.16.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.