While political discourse often collapses “religion” into opposition, the historical record shows a deep and continuous current of faith-based advocacy for reproductive choice.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The modern debate often casts religion and abortion as natural adversaries. American political discourse, particularly since the late twentieth century, has been shaped by Catholic and evangelical opposition to abortion. Yet this framing obscures a parallel tradition: a robust, if sometimes quieter, history of religious support for abortion access. Clergy, congregations, and denominations across Protestant, Jewish, and Unitarian traditions have defended reproductive choice as a moral imperative rooted in compassion, justice, and conscience.

To uncover this history is to reveal a far more complicated religious landscape than the one dominant in contemporary rhetoric. It shows that support for abortion has deep roots in theological interpretation, pastoral practice, and collective activism.

Early American Context: Silence and Accommodation

In colonial and early republican America, abortion was not uniformly condemned. Before the “quickening” of fetal movement, usually around the fourth or fifth month of pregnancy, abortion was rarely treated as a crime. Religious discourse reflected this standard. Puritan sermons thundered against sexual immorality and illegitimacy, but few clergy addressed abortion directly. For many Protestants, early termination was considered a private matter rather than a theological crisis.1

The absence of sharp religious opposition before the mid-nineteenth century is itself significant. In a culture where clergy frequently pronounced on sin, silence suggests tacit acceptance. Protestantism in this period focused moral teaching on sexual order and patriarchal authority, leaving abortion largely to the realm of custom and medicine.

Nineteenth Century: Divergence between Catholics and Protestants

By the mid-nineteenth century, religious positions began to harden. The Catholic Church, drawing on Thomist theology and papal encyclicals, increasingly condemned abortion at all stages. This stance helped distinguish Catholic identity in a Protestant-majority society.2

Protestant leaders, however, often adopted more flexible views. Many echoed medical consensus, which regarded abortion after quickening as morally problematic but early procedures as ambiguous. Some clergy framed the issue in pastoral terms, recognizing that women often sought abortions under economic duress or social stigma. This divergence between Catholic absolutism and Protestant ambivalence created the conditions for later ecumenical divides.

It was also in this century that early feminists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Victoria Woodhull raised questions about reproductive autonomy. While their focus was often on resisting male exploitation, some arguments overlapped with religious concerns about women’s health and dignity. The seeds of religiously grounded support for reproductive choice were planted in these reform circles, even if not yet fully articulated.

Early Twentieth Century: Progressive Religion and the Social Gospel

The early twentieth century witnessed a new alignment. Progressive Protestantism, shaped by the Social Gospel, began to emphasize the moral duty to improve living conditions for women and families. While few clergy declared abortion “moral,” many treated it as sometimes necessary, particularly in cases of medical danger. Ministers such as Harry Emerson Fosdick and other liberal Protestants argued that Christian ethics required compassion for women in distress.3

Jewish communities, particularly within Reform Judaism, provided more explicit support. Rabbinic tradition had long held that the fetus was part of the woman’s body rather than an independent soul until birth. As a result, abortion was not only permitted but sometimes required if the mother’s health, physical or psychological, was at risk.4 This principle, grounded in halakhic interpretation, made Judaism a consistently pro-choice voice throughout the twentieth century.

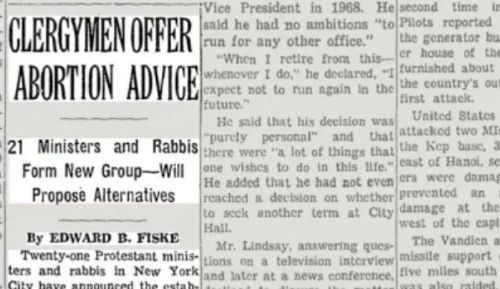

The Clergy Consultation Service and Pre-Roe Activism

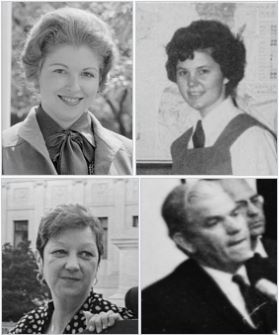

The most visible expression of religious support for abortion emerged in the 1960s. In 1967, a group of Protestant ministers and Jewish rabbis in New York founded the Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion (CCS). Their mission was clear: provide women with counseling and safe referrals at a time when abortion was still largely illegal. By the early 1970s, CCS included more than 2,000 clergy nationwide.5

These pastors and rabbis publicly grounded their work in religious duty. They argued that compassion, pastoral care, and the sanctity of women’s lives outweighed restrictive laws. For many, helping women obtain safe abortions was an act of conscience.

Denominational statements soon followed. The United Methodist Church, Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), Episcopal Church, and United Church of Christ all issued resolutions supporting legal abortion under broad circumstances. Reform and Conservative Jewish bodies reaffirmed long-standing positions that prioritized the health and autonomy of the woman. Even the Southern Baptist Convention, which would later become a flagship anti-abortion denomination, passed resolutions in 1971 and 1974 affirming abortion law reform in cases of rape, incest, fetal abnormality, or threat to the mother.6

Post-Roe Coalitions and Religious Advocacy

When Roe v. Wade legalized abortion in 1973, supportive clergy did not retreat. Instead, they organized more formally. The Religious Coalition for Abortion Rights (later renamed the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice) was founded in 1973 to preserve the gains of Roe. It included mainline Protestant denominations, Reform and Conservative Jewish groups, Unitarian Universalists, and progressive Catholic voices.

These coalitions reframed abortion as not only a constitutional right but also a matter of religious freedom. They argued that in a pluralistic society, no single religious interpretation of abortion should dominate public law. For Jewish groups in particular, restricting abortion was seen as a violation of their religious liberty, since Jewish law sometimes required abortion to protect the woman’s health.7

Through the 1980s and 1990s, this coalition faced increasing opposition from the Christian Right. Yet religious support for abortion remained a steady, if less visible, current. Clergy continued to provide counseling, advocacy, and public witness.

Contemporary Landscape

Today, the religious debate over abortion is polarized, but the tradition of support remains active. Reform, Conservative, and Reconstructionist Judaism continue to affirm abortion as morally permissible and sometimes necessary. Mainline Protestant denominations (including the Episcopal Church, Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), United Methodist Church, United Church of Christ, and Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) maintain policies that support abortion access with pastoral discretion. Unitarian Universalists are among the most vocal advocates for reproductive rights.

Progressive Catholic voices, though not sanctioned by the hierarchy, remain visible through groups like Catholics for Choice. They argue that Catholic social teaching on conscience and justice supports reproductive autonomy. These voices demonstrate that “religious America” is not monolithic on abortion.

Conclusion

The history of religious support for abortion in America is long and varied. It begins with Protestant silence under the quickening standard, grows through Jewish legal tradition, expands in the Social Gospel’s emphasis on women’s welfare, and finds bold expression in the Clergy Consultation Service of the 1960s and the post-Roe coalitions. While political discourse often collapses “religion” into opposition, the historical record shows a deep and continuous current of faith-based advocacy for reproductive choice.

In moments of crisis, clergy and congregations turned not to condemnation but to compassion, framing abortion as a matter of conscience, justice, and pastoral care. That tradition, though sometimes overshadowed, remains alive, reminding us that religion in America has never spoken with only one voice on abortion.

Appendix

Footnotes

- James C. Mohr, Abortion in America: The Origins and Evolution of National Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), 20–23.

- John T. Noonan, Contraception: A History of Its Treatment by the Catholic Theologians and Canonists (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965), 398–403.

- Harry Emerson Fosdick, On Being a Real Person (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1943), 132–134.

- David M. Feldman, Birth Control in Jewish Law (New York: New York University Press, 1968), 213–216.

- Cynthia R. Greenlee, “Gillian Frank: Before Abortion Was Legal, Clergy Networks Provided Connections to Reproductive Care,” Faith & Leadership (Duke University, 2023).

- Daniel K. Williams, Defenders of the Unborn: The Pro-Life Movement Before Roe v. Wade (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 164–167.

- Rebecca Todd Peters, Trust Women: A Progressive Christian Argument for Reproductive Justice (Boston: Beacon Press, 2018), 55–58.

Bibliography

- Feldman, David M. Birth Control in Jewish Law. New York: New York University Press, 1968.

- Fosdick, Harry Emerson. On Being a Real Person. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1943.

- Greenlee, Cynthia R. “Gillian Frank: Before Abortion Was Legal, Clergy Networks Provided Connections to Reproductive Care.” Faith & Leadership, Duke University, March 7, 2023. https://faithandleadership.com/gillian-frank-abortion-was-legal-clergy-networks-provided-connections-reproductive-care

- Mohr, James C. Abortion in America: The Origins and Evolution of National Policy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

- Noonan, John T. Contraception: A History of Its Treatment by the Catholic Theologians and Canonists. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965.

- Peters, Rebecca Todd. Trust Women: A Progressive Christian Argument for Reproductive Justice. Boston: Beacon Press, 2018.

- Williams, Daniel K. Defenders of the Unborn: The Pro-Life Movement Before Roe v. Wade. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.17.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.