George Washington’s genius did not rest in tactical brilliance alone. His achievement was to hold together an army under circumstances that would have destroyed most forces.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

When George Washington accepted the appointment as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army in June 1775, he inherited not a professional force but an assemblage of regional militias, driven as much by local pride as by collective discipline. The Revolutionary cause demanded the creation of a standing army capable of resisting the British Empire, the most formidable military power of its time. Yet Washington’s greatest battles were not always against redcoats. They were fought in the realm of logistics, training, recruitment, and morale, where the fragility of American unity constantly threatened collapse. Historians have long emphasized Washington’s prudence on the battlefield, but his most enduring accomplishment lay in simply keeping the army alive through deprivation, desertion, and political indifference.1

Origins of the Continental Army

From Militias to National Force

The Revolution began with local militias: men who gathered at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, armed with their own muskets and bound by their townships. Such units carried deep symbolic value, affirming that ordinary Americans could rise to defend liberty. Yet their weaknesses were clear. Militias often elected their own officers, disbanded after short service, and resisted any command that conflicted with local interests.2 Washington, arriving at Cambridge in July 1775, quickly realized that an army based purely on militia traditions could never withstand professional British regulars.

The Continental Congress therefore authorized the creation of a national army. But Congress, reluctant to centralize too much power, left it weakly funded and dependent upon the goodwill of the states. Washington stepped into a command where military necessity and republican suspicion of standing armies collided. His challenge was not only to organize soldiers but to persuade legislators that a permanent force would not become a tyrannical instrument.3

Washington’s Early Command

What Washington found in Massachusetts was sobering: half-trained men short of powder and shot, dressed in mismatched civilian clothes, and governed by loose chains of authority. Even the physical infrastructure was lacking. Ammunition supplies could scarcely support a single engagement, and uniforms were non-existent. Early reports speak of soldiers drilling barefoot in the mud while officers begged local committees for powder horns and blankets.4 Washington’s first test was not against General Gage but against chaos itself.

Recruitment and Retention Struggles

Short-Term Enlistments

From the outset, Congress and the states insisted upon short enlistment periods, typically one year. Such terms preserved civilian ideals of temporary service but created military nightmares. As the year’s end approached, Washington watched his army melt away. In December 1776, on the eve of British offensives, he warned Congress that his force would dissolve within days unless drastic measures were taken.5 The celebrated crossing of the Delaware at Trenton was as much an act of desperation as strategy: a bid to keep an army together by demonstrating that the cause still had vitality.

Competition with State Militias

States guarded their militias jealously. Governors preferred local defense over national service, and many communities resisted sending men into a distant Continental establishment. In some cases, local militias received better pay and supplies than national soldiers, luring recruits away. Washington lamented this rivalry, which weakened the possibility of a unified army. He understood that without centralization, the Revolution could not survive, yet his voice often clashed with state particularism.6

At times, these divisions created near farcical consequences. Massachusetts militiamen, for example, might refuse to serve outside their own borders, while men from Pennsylvania declined orders that took them farther north. Washington, charged with orchestrating a continental effort, found himself commanding forces that were continental in name only. The Continental Army existed as a patchwork, stitched together with tenuous threads of state loyalty, and its fragility reflected the deeper uncertainty of American union in its earliest stage.16

Incentives and Desertion

To fill the ranks, Congress and the states offered bounties of cash or land. These incentives attracted recruits but created other problems: many enlisted for the bounty only to desert once paid, repeating the process elsewhere. Soldiers endured hunger, ragged clothing, and months without wages. Desertion was endemic, and Washington, though stern in discipline, recognized that punishment alone could not cure the army’s plight. He needed Congress to supply the basic necessities that gave men a reason to stay.7

Lack of Widespread Agreement and Loyalist Opposition

Recruitment was also undermined by the fact that not all Americans supported independence. Loyalists, whether from conviction, economic ties, or fear of anarchy, opposed rebellion and often aided British forces. In New York, New Jersey, and the Carolinas, Loyalist sentiment was strong, creating zones where Washington struggled to draw recruits. Many colonists preferred neutrality, reluctant to risk their lives for a cause they viewed as radical. Thus, Washington fought not only to recruit men but against a divided society that complicated the dream of a national army.8

Training and Discipline

The Problem of Militia Culture

American soldiers brought with them a culture of independence. Militiamen were unaccustomed to the strict discipline that characterized European armies. Washington, shaped by his service in the French and Indian War, insisted upon professional order: saluting, drilling, and obeying without question. Resistance was fierce, as men who saw themselves as citizens bristled at what seemed aristocratic severity. Washington’s resolve on this point reflected his conviction that liberty and discipline were not mutually exclusive but mutually necessary.9

The tension between military order and republican independence created constant friction. To enforce discipline too harshly risked alienating men who believed they had volunteered freely, yet to allow indiscipline threatened collapse in battle. Courts-martial became frequent, but Washington exercised clemency as often as severity, seeking to mold a professional force without breaking the democratic spirit that defined it. The problem of militia culture thus became a mirror of the Revolution itself: balancing liberty with authority.17

The Role of Foreign Officers

The arrival of foreign officers marked a turning point. Baron Friedrich von Steuben, a Prussian veteran, introduced systematic drilling during the winter at Valley Forge. His “Blue Book” manual standardized maneuvers, while his blunt charisma earned the respect of soldiers who had previously scorned European rigidity. The Marquis de Lafayette, though young, provided a bridge between American enthusiasm and French military expertise. Their contributions, alongside others like Pulaski and Kosciuszko, professionalized the army and gave it tactical coherence it had previously lacked.10

Balancing Idealism and Pragmatism

Washington’s struggle was not simply to impose drill but to reconcile it with revolutionary ideals. Soldiers fought for liberty, not servitude, and Washington’s challenge was to cultivate obedience without extinguishing the very spirit of independence that sustained them. He succeeded in part by example: enduring the same conditions as his men, refusing luxury when they starved, and blending sternness with appeals to patriotism. In his leadership, pragmatism and principle converged.

Supply and Logistics

Chronic Shortages

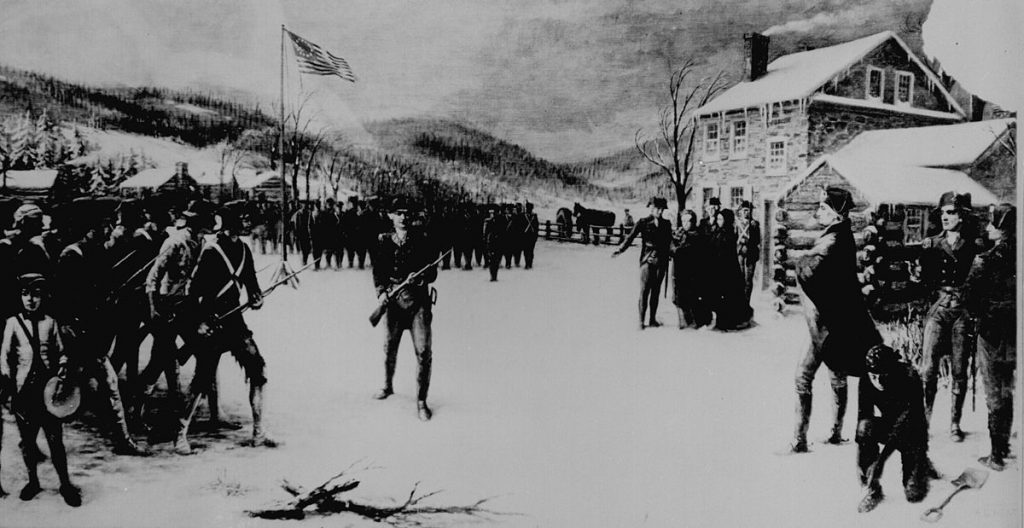

The army’s most visible weakness lay in its supply system. Soldiers went months without shoes, marching in bloody footprints across the snow. Muskets were scarce, powder scarcer still. The winter at Valley Forge, remembered as a symbol of endurance, was in fact a crisis of logistics. Men built crude huts from timber, huddled against cold, and scrounged for food while disease cut through the ranks.11 Washington could fight battles only when provisions allowed; strategy was tethered to supply.

Inefficiencies of the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress lacked the power to tax directly, relying instead on requisitions from states. Many states delayed or refused to deliver. Inflation rendered Continental currency nearly worthless, eroding soldiers’ wages. Contractors and commissaries often proved corrupt or incompetent. Washington repeatedly warned Congress that his army teetered on the brink of collapse not because of British strength but because of American neglect.12

The political philosophy of the Revolution itself deepened these problems. Having risen against imperial authority, Congress hesitated to establish strong central control. This ideological reluctance meant that even wartime measures were compromised by fear of concentrating power. Washington lived with the consequences: ragged soldiers, empty magazines, and a government unable to act with the urgency military necessity required.18

Moreover, factional disputes within Congress aggravated supply failures. Regional jealousies ensured that some states resented supporting campaigns fought in other theaters. Delegates debated endlessly while wagons of food and ammunition failed to arrive. Washington, who valued unity above all, saw in these divisions a greater threat to independence than British muskets. His correspondence brims with frustration at politicians who spoke of liberty while starving its defenders.19

Washington’s Administrative Burden

Much of Washington’s energy was consumed not in commanding troops but in pleading for supplies. His letters to Congress, governors, and quartermasters form a record of constant frustration. He micromanaged food distribution, clothing inventories, and medical shortages. Leadership meant not only directing battles but performing the exhausting labor of keeping men fed, clothed, and armed. The Revolution, he understood, could be lost not in defeat but in hunger.

Morale and Cohesion

Hardship and Mutiny

Mutinies erupted as deprivation mounted. In 1781, the Pennsylvania Line mutinied, demanding overdue pay and relief from intolerable service. Similar unrest followed in New Jersey. Washington feared these incidents would unravel the fragile army, yet he responded with a combination of firmness and conciliation, punishing ringleaders but negotiating with the rank and file.

The most dangerous moment came with the Newburgh Conspiracy in 1783, when officers, unpaid and frustrated, contemplated using force to secure pensions. Washington’s response – reminding them of their sacrifices, and humbly donning his spectacles as he confessed his own “growing old and now going blind – disarmed their anger with a blend of pathos and authority. His intervention prevented what might have been a coup and preserved the republican principle of civilian control of the military.13

Symbolic Leadership

Washington’s mere presence sustained morale. At Valley Forge, he shared the conditions of his soldiers, dining sparingly, riding among the huts, and enduring winter with them. His refusal to insulate himself from hardship created a bond that transcended material deprivation. Men followed him not simply because he commanded but because he embodied their cause. In this sense, Washington was less a general in the European mold than a republican patriarch whose authority rested on trust.

The Army and Revolutionary Politics

Civilian Oversight

Washington’s leadership unfolded within a republican framework that distrusted military power. The Continental Congress feared a standing army as the seed of tyranny. Washington, sensitive to these fears, walked a narrow path. He consistently deferred to civilian authority, even when Congress failed to provide support. His political restraint, refusing to grasp at dictatorial powers even when urged, established precedents that would endure in American civil-military relations.14

At the same time, Washington understood the fragility of this balance. Too much deference risked leaving his army destitute, while too much assertion risked accusations of ambition. His mastery lay in preserving obedience without humiliation, pressing Congress firmly but never defiantly. By maintaining this equilibrium, he not only saved the army but also reassured a fledgling republic that liberty could survive war.20

The Newburgh Conspiracy

Though mentioned earlier as a mutiny, the Newburgh episode also illuminates the relationship between army and state. Officers, embittered by years without pay, gathered in March 1783 to consider collective action. Washington appeared unexpectedly, delivered his now-famous appeal, and turned a potential rebellion into a moment of loyalty. By acknowledging his own frailty, he reminded his men that they fought not for personal gain but for a republican ideal. The crisis ended peacefully, but its shadow revealed how fragile the new republic might have been had Washington lacked the moral authority to restrain his officers.15

Conclusion

George Washington’s genius did not rest in tactical brilliance alone. His achievement was to hold together an army under circumstances that would have destroyed most forces: short enlistments, lack of pay, constant desertion, inadequate supplies, and deep political division. He forged a national army from fragments of state militias, imposed discipline on citizen-soldiers, and navigated a Congress both fearful and neglectful. The Continental Army was never an instrument of unbroken victories, but it was an instrument of endurance.

In this endurance lay the Revolution’s survival. Washington’s difficulties in establishing, training, and maintaining the army illuminate the tension between republican ideals and the necessities of war. They reveal how military cohesion was inseparable from political unity, and how leadership was tested less in triumph than in persistence. From Cambridge to Valley Forge to Newburgh, Washington preserved not just an army but the possibility of independence itself.

Appendix

Notes

- Joseph Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (New York: Knopf, 2004), 66–70.

- John Shy, A People Numerous and Armed: Reflections on the Military Struggle for American Independence (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990), 49–52.

- Jack Rakove, Revolutionaries: A New History of the Invention of America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010), 153–55.

- David Hackett Fischer, Washington’s Crossing (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 27–29.

- Ellis, His Excellency, 92–94.

- Shy, A People Numerous and Armed, 64–66.

- Charles Royster, A Revolutionary People at War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979), 110–13.

- Maya Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World (New York: Vintage, 2011), 37–40.

- Fischer, Washington’s Crossing, 102–04.

- Paul Lockhart, The Drillmaster of Valley Forge: The Baron de Steuben and the Making of the American Army (New York: HarperCollins, 2008), 141–44.

- Royster, A Revolutionary People at War, 198–200.

- Rakove, Revolutionaries, 189–91.

- Richard Kohn, Eagle and Sword: The Federalists and the Creation of the Military Establishment in America, 1783–1802 (New York: Free Press, 1975), 25–27.

- Ellis, His Excellency, 143–46.

- James Flexner, George Washington in the American Revolution, 1775–1783 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1968), 485–88.

- Shy, A People Numerous and Armed, 73–76.

- Royster, A Revolutionary People at War, 119–21.

- Rakove, Revolutionaries, 193–96.

- Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Vintage, 1991), 176–80.

- Ellis, His Excellency, 147–50.

Bibliography

- Ellis, Joseph. His Excellency: George Washington. New York: Knopf, 2004.

- Fischer, David Hackett. Washington’s Crossing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Flexner, James. George Washington in the American Revolution, 1775–1783. Boston: Little, Brown, 1968.

- Jasanoff, Maya. Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World. New York: Vintage, 2011.

- Kohn, Richard. Eagle and Sword: The Federalists and the Creation of the Military Establishment in America, 1783–1802. New York: Free Press, 1975.

- Lockhart, Paul. The Drillmaster of Valley Forge: The Baron de Steuben and the Making of the American Army. New York: HarperCollins, 2008.

- Rakove, Jack. Revolutionaries: A New History of the Invention of America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010.

- Royster, Charles. A Revolutionary People at War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979.

- Shy, John. A People Numerous and Armed: Reflections on the Military Struggle for American Independence. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. New York: Vintage, 1991.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.18.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.