Pseudoscience and conspiracy theories are not fringe anomalies but recurring features of human history, shadows that accompany the light of reason.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

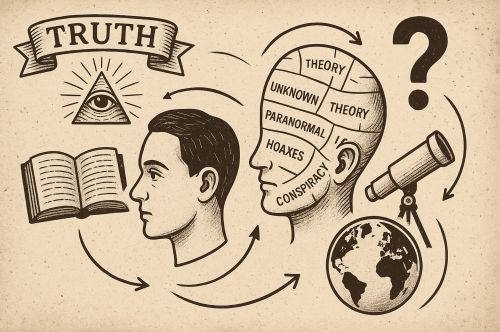

The human longing for hidden knowledge has been both a source of creative speculation and a recurring threat to rational inquiry. Pseudoscience and conspiracy thinking, often dismissed as modern aberrations, in fact represent a continuous undercurrent within intellectual history. They offer not merely alternative explanations but alternative identities, communities defined by their rejection of consensus and their embrace of “invented truths.” To trace this lineage is to confront the shadow side of the human pursuit of knowledge: the capacity to resist evidence, to valorize myth, and to weaponize falsehoods for social or political power.

What follows situates contemporary phenomena like Flat Earth revivalism, moon landing denial, and ancient alien theories within a broader genealogy that stretches from antiquity through the digital age.

Early Examples: Authority and the Rejection of Observation

Long before YouTube algorithms could funnel the curious into rabbit holes, cosmological claims untethered from observation commanded widespread belief. Mesopotamian and early Greek traditions frequently imagined a flat earth, a disk encircled by ocean, despite observational clues that contradicted this image.

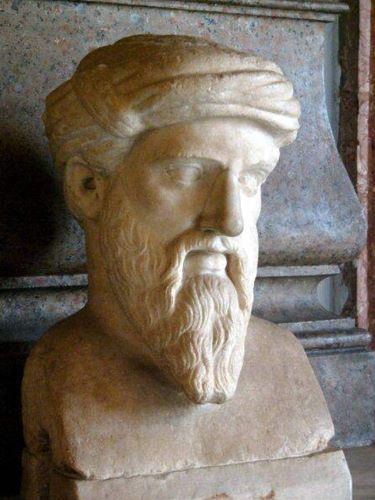

By the sixth century BCE, Greek philosophers had not only proposed but demonstrated the earth’s sphericity. Pythagorean thinkers advanced the model, and Aristotle later marshaled clear observational proofs: the curved shadow of the earth on the moon during an eclipse, the changing visibility of constellations by latitude, and the gradual disappearance of ships over the horizon.1 Eratosthenes’ third-century BCE calculation of the earth’s circumference was astonishingly accurate, further securing the spherical model within learned circles.2

What is often forgotten in popular retellings is that this knowledge endured. Medieval scholars, from Augustine and Isidore of Seville to Thomas Aquinas, accepted a spherical earth as established fact. Sailors navigating by stars and scholars studying Aristotle’s De caelo (On the Heavens) did not imagine a flat disk-world.3 The notion of a widespread “flat earth belief” among the educated is largely a nineteenth-century invention, popularized by polemicists eager to portray the Middle Ages as an age of darkness. The flat earth existed mainly in the common imagination, not in the learned tradition.4

Astrology, meanwhile, illustrates the early entanglement of rational inquiry with speculative fantasy. Babylonian star charts represented genuine astronomical achievement, yet they were bound to a belief that planetary motions dictated human destiny. The persistence of astrology into the medieval and even modern period underscores the durability of explanatory systems that promise certainty amid uncertainty.5

Alchemy represents another case of dual inheritance: on the one hand, an experimental tradition that contributed to the development of chemistry; on the other, a mystical search for transmutation and eternal life. Its most enduring legacy was not the philosopher’s stone but the demonstration that practices blending empirical method with fantastical aims can persist for centuries.6

The Age of Discovery and Skepticism

The so-called scientific revolution did not vanquish conspiracy-like resistance to evidence. When Copernicus advanced heliocentrism in De revolutionibus (1543), his claims challenged not only geocentric astronomy but the theological order that anchored it. Opposition to heliocentrism resembled modern conspiratorial patterns: accusations that such claims were designed to deceive the faithful or undermine authority. Galileo’s later trial dramatized this conflict between observation and entrenched power.7

The Age of Discovery likewise produced tensions between eyewitness experience and fantastical expectation. Reports of “New World” peoples were filtered through medieval ethnography populated by monstrous races: dog-headed men, Amazons, and giants.8 Such imaginings were less about empirical description than about sustaining inherited frames of reference. Fantastical geographies functioned as early forms of pseudoscience: interpretive systems designed to resist rather than assimilate disruptive evidence.

19th-Century Pseudoscience and the Allure of Certainty

Industrial modernity, with its promises of progress and empiricism, paradoxically generated a flourishing of pseudoscientific enterprises. Phrenology, developed by Franz Joseph Gall, promised the ability to read moral and intellectual character from the shape of the skull. It cloaked prejudice in scientific rhetoric, reinforcing racial and class hierarchies under the guise of measurement.9

The spiritualist movement of the mid-nineteenth century offered another kind of certainty. Séances and table-rapping promised communion with the dead at precisely the moment when industrialization and urbanization unsettled traditional community structures. This was not fringe entertainment but mass culture, embraced by figures ranging from middle-class families to intellectuals.10

Atlantis theories, popularized by Ignatius Donnelly in his 1882 Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, transmuted Plato’s allegory into pseudo-archaeology. Donnelly’s claims lent support to colonial ideologies by suggesting that advanced “lost civilizations,” often coded as racially distinct, were responsible for achievements otherwise attributed to non-European peoples.11

20th-Century Myths and Manufactured Mysteries

If the nineteenth century dressed pseudoscience in the garb of scientific measurement, the twentieth weaponized it in explicitly political forms. Nazi occultism, fostered by groups like the Thule Society, fused pseudo-historical claims about Aryan origins with esoteric mythologies. This blend of pseudoscience and nationalism provided a spiritualized foundation for racial ideology and genocide.12

Cold War anxieties fostered new myths. The 1947 Roswell incident birthed a UFO mythology that framed the government itself as conspirator-in-chief, hiding alien knowledge from the public.13 By the late 1960s and 1970s, moon landing hoax theories flourished, fueled by distrust of government and mass media, a pattern that prefigures today’s conspiratorial ecosystems.14

Ancient astronaut theories, popularized by Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods? (1968), offered a narrative in which human civilization’s greatest achievements were not human at all. The racial subtext of such claims, attributing the pyramids or the Nazca lines to extraterrestrials rather than to the ingenuity of non-Western peoples, underscores the ideological work pseudoscience continues to perform.15

The Digital Age Resurgence

If pseudoscience once traveled by pamphlet, séance, or pulp press, today it travels at the speed of the algorithm. Flat Earth societies, once dwindling curiosities, have been reborn through YouTube channels that generate both revenue and community for their adherents.16 What distinguishes this new moment is not the content of the claims, the earth remains flat only in their imagination, but the infrastructure of amplification.

QAnon, anti-vaccination movements, and climate denialism exemplify the same dynamics. Each insists that hidden knowledge exists just beyond the reach of the mainstream, accessible only to the enlightened few. The result is not merely belief but identity: belonging to a community defined by resistance to consensus.17

These movements are global, tied together by memes, influencers, and the performative rejection of “official narratives.” The “hidden truth” becomes less about what is claimed (aliens, elites, or vaccines) and more about the act of disbelief itself.

Analysis: The Enduring Allure of Hidden Knowledge

Why does pseudoscience persist across millennia? Psychologically, it offers comfort in a chaotic world, transforming randomness into order and complexity into simplicity. Sociopolitically, it serves as a weapon for power, whether in Nazi mythologies or in the contemporary politics of disinformation.18 At the level of identity, it offers community for those alienated from institutions or eager to define themselves against them.

The continuity across time is striking. Flat Earth cosmologies, Atlantis myths, and ancient astronaut theories wear different costumes but enact the same archetype: the refusal of consensus knowledge and the embrace of explanatory fantasies that reaffirm suspicion, identity, or ideology.

Conclusion

To understand today’s conspiratorial culture, we must recognize its deep historical roots. Pseudoscience and conspiracy theories are not fringe anomalies but recurring features of human history, shadows that accompany the light of reason. If science represents our collective attempt to discipline knowledge through evidence, pseudoscience represents our equally persistent attempt to resist that discipline. To ignore this genealogy is to mistake contemporary crises for novelties, rather than for echoes in an old and enduring conversation.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Aristotle, On the Heavens, trans. W. K. C. Guthrie (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1939).

- Cleomedes, On the Circular Motions of the Celestial Bodies, trans. Alan C. Bowen and Robert B. Todd (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, I.q.1.a.1.

- Jeffrey Burton Russell, Inventing the Flat Earth: Columbus and Modern Historians (New York: Praeger, 1991).

- Tamsyn Barton, Ancient Astrology (London: Routledge, 1994).

- Lawrence M. Principe, The Secrets of Alchemy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012).

- Maurice Finocchiaro, Retrying Galileo, 1633–1992 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

- John B. Friedman, The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1981).

- Roger Cooter, The Cultural Meaning of Popular Science: Phrenology and the Organization of Consent in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984).

- Alex Owen, The Darkened Room: Women, Power, and Spiritualism in Late Victorian England (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989).

- Ignatius Donnelly, Atlantis: The Antediluvian World (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1882).

- Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, The Occult Roots of Nazism (New York: New York University Press, 1985).

- David M. Jacobs, The UFO Controversy in America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975).

- Philip Plait, Bad Astronomy: Misconceptions and Misuses Revealed, from Astrology to the Moon Landing “Hoax” (New York: Wiley, 2002).

- Erich von Däniken, Chariots of the Gods? (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1968).

- Flat Earth Society, “History of the Flat Earth,” accessed September 18, 2025, https://www.tfes.org.

- Mike Rothschild, The Storm Is Upon Us: How QAnon Became a Movement, Cult, and Conspiracy Theory of Everything (New York: Melville House, 2021).

- Michael Butter, The Nature of Conspiracy Theories (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2020).

Bibliography

- Aristotle. On the Heavens. Translated by W. K. C. Guthrie. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1939.

- Barton, Tamsyn. Ancient Astrology. London: Routledge, 1994.

- Butter, Michael. The Nature of Conspiracy Theories. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2020.

- Cleomedes. On the Circular Motions of the Celestial Bodies. Translated by Alan C. Bowen and Robert B. Todd. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

- Cooter, Roger. The Cultural Meaning of Popular Science: Phrenology and the Organization of Consent in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- Donnelly, Ignatius. Atlantis: The Antediluvian World. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1882.

- Finocchiaro, Maurice. Retrying Galileo, 1633–1992. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

- Flat Earth Society. “History of the Flat Earth.” Accessed September 18, 2025.

- Friedman, John B. The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1981.

- Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. The Occult Roots of Nazism. New York: New York University Press, 1985.

- Jacobs, David M. The UFO Controversy in America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975.

- Owen, Alex. The Darkened Room: Women, Power, and Spiritualism in Late Victorian England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

- Plait, Philip. Bad Astronomy: Misconceptions and Misuses Revealed, from Astrology to the Moon Landing “Hoax”. New York: Wiley, 2002.

- Principe, Lawrence M. The Secrets of Alchemy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton. Inventing the Flat Earth: Columbus and Modern Historians. New York: Praeger, 1991.

- Rothschild, Mike. The Storm Is Upon Us: How QAnon Became a Movement, Cult, and Conspiracy Theory of Everything. New York: Melville House, 2021.

- Thomas Aquinas. Summa Theologica. Translations vary.

- von Däniken, Erich. Chariots of the Gods? New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1968.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.19.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.