This project threatens to recast the United States as a nation where faith and citizenship are indistinguishable, and where dissent is framed as both unpatriotic and ungodly.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Last week, the U.S. Department of Education announced it had partnered with dozens of conservative organizations to promote “patriotic” civics lessons in public schools, a move critics argue risks blurring the line between civic instruction and partisan indoctrination. Among the groups highlighted was Turning Point USA, a conservative activist network that has sought to expand its reach beyond college campuses by creating “chapters” in K–12 schools.

That announcement set the stage for another headline this week: the resignation of Oklahoma State Superintendent Ryan Walters, a staunch proponent of embedding religion in education. Walters stepped down to lead a conservative Christian group, reinforcing concerns that public schools are becoming a frontline for Christian nationalist politics.

Turning Point USA and Education

Turning Point USA, long a presence on college campuses for its culture-war messaging, is now extending its reach into public schools. Under the guise of civics education, the group has pushed for chapters in high schools that promote its brand of political activism, often blending calls for “patriotism” with attacks on progressive curricula. Supporters frame these efforts as an antidote to what they call “leftist indoctrination,” while opponents see them as a Trojan horse for partisan politics.

The Department of Education’s decision to include Turning Point USA among its civic partners gives the organization a level of legitimacy it has rarely enjoyed within K–12 education. For critics, that endorsement raises red flags: it suggests that schools may soon be pressured to adopt programming tied to one ideological worldview rather than a pluralistic understanding of civic life. The prospect of “patriotic clubs” modeled after Turning Point’s campus chapters has alarmed educators who fear that history and civics will be filtered through a lens of nationalism and religious conservatism.

Christian Nationalist Network in Action

Turning Point USA is only one part of a sprawling coalition. A host of Christian nationalist organizations are working in tandem to push religion into public education and law under the banner of civic renewal. These groups include the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR), the Council for National Policy (CNP), Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), Family Research Council (FRC), First Liberty Institute, American Center for Law and Justice (ACLJ), Center for Renewing America (CRA), National Religious Broadcasters (NRB), and the touring initiative known as The Courage Tour.

Though their missions vary, from legal advocacy to media influence to grassroots mobilization, they share a common goal: to entwine Christianity with American identity and policy. Their combined efforts represent a coordinated campaign, not isolated actions. In schools, that means lobbying for curricula that stress nationalism as a moral duty; in courts, it means litigating for religious privilege in public institutions. Taken together, the network represents a powerful front advancing what critics call an “Americanized” Christianity, one that prioritizes cultural dominance over pluralism.

The Religious Agenda Behind “Patriotism”

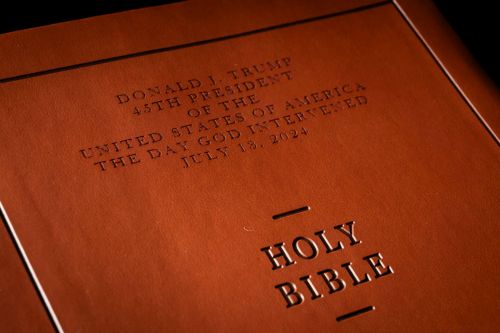

While the Department of Education frames its initiative as a renewal of civic literacy, many of the groups involved see “patriotism” as a vehicle for advancing religious nationalism. Lesson plans and club activities promoted by these organizations often blur civic instruction with theological messaging, stressing the idea that America was founded as a Christian nation and should be reclaimed as such. The flag, the cross, and the Constitution are presented as inseparable symbols of national destiny.

Critics warn that this reframing of civics education is less about fostering engaged citizenship than about embedding a singular religious ideology into public life. By placing “God and country” at the center of civic identity, such programs risk marginalizing students from other faith traditions, or none at all, and eroding the constitutional principle of church-state separation. What is being marketed as a patriotic revival is, for many, a calculated attempt to sanctify one version of history and silence competing perspectives.

The rhetoric of “patriotism” also functions strategically, softening the harder edges of religious nationalism by cloaking it in familiar civic language. Few parents or educators object to patriotism in principle, but when patriotism becomes a proxy for mandatory Christian values, the line between civic pride and sectarian dogma begins to vanish. In this way, the campaign reframes dissent as disloyalty, leaving little room for the pluralism and critical inquiry that public education is meant to safeguard.

Theological and Scriptural Contradictions

At the heart of the Christian nationalist project lies a profound irony: the movement’s claim to scriptural authority often runs counter to the teachings of the very figure it seeks to exalt. In the Gospels, Jesus resists political power, rejects violence, and challenges the fusion of religious authority with state control. He tells his followers that his kingdom “is not of this world” and warns against laying up treasures on earth. Yet the Americanized Christianity advanced in these civics initiatives treats political power as divine mandate and equates loyalty to the nation with loyalty to God.

Theologians and clergy critical of Christian nationalism note that this ideology distorts the New Testament message, replacing the ethic of humility and service with one of dominance and exclusion. Far from defending freedom of conscience, Christian nationalism often seeks to impose conformity, elevating one version of Christianity above all others. The Jesus who ate with outcasts and defended the marginalized would, they argue, stand against efforts to bind faith to state power.

For many Christians, then, the danger is not simply civic; it is spiritual. By merging Christianity with nationalism, these movements risk creating an idol of the nation itself, worshiping a political project rather than the transcendent God of scripture. In doing so, they redefine discipleship as patriotism and mistake cultural supremacy for divine mission.

Political and Social Implications

The push to merge patriotic civics with religious nationalism is not limited to classrooms; it reflects a broader strategy to reshape American society. By embedding these ideas in education, advocates aim to form a generation of students who equate Christianity with national identity and see political power as a sacred trust. This vision dovetails with conservative legislative agendas that seek to privilege Christian symbols, language, and policies in public life, often at the expense of religious minorities and secular voices.

For critics, the danger lies in how quickly civics can become weaponized. Once loyalty to country is defined through a religious lens, dissenters can be cast as enemies of both God and nation. Such framing fuels polarization, undercuts democratic pluralism, and risks eroding long-standing protections for religious freedom. What begins as “patriotic education” can slide into a culture where disagreement is treated as betrayal and public institutions serve the interests of a single faith tradition.

The implications are global as well as domestic. Nations that have pursued similar projects, blending religious identity with political power, have often seen the suppression of minority groups and the narrowing of democratic space. For the United States, a country built on constitutional guarantees of religious liberty, the rise of Christian nationalism poses a challenge not only to the classroom but to the credibility of its democratic ideals.

Adding to the concern is the coordinated nature of this movement. The alignment of advocacy groups, legal organizations, and political figures ensures that the message is amplified across multiple platforms, from classrooms to courtrooms, from pulpits to legislatures. This creates a feedback loop where educational initiatives reinforce political campaigns, and political victories embolden further incursions into civic life. Left unchecked, the result could be a self-sustaining cycle of religious nationalism woven tightly into the fabric of American governance.

Conclusion

The Department of Education’s embrace of conservative groups to promote “patriotic” civics may look on the surface like a harmless effort to encourage civic pride. But paired with the resignation of Ryan Walters to lead a Christian organization, and with the mobilization of powerful networks like ADF, FRC, and Turning Point USA, the initiative reveals a deeper contest over the nation’s identity. Schools, once envisioned as neutral spaces for democratic learning, are becoming battlegrounds in a struggle to redefine what it means to be American.

Critics argue that this project threatens to recast the United States as a nation where faith and citizenship are indistinguishable, and where dissent is framed as both unpatriotic and ungodly. Such a shift not only undermines constitutional principles of pluralism and religious liberty but also risks turning civic education into a tool of exclusion rather than empowerment.

As Christian nationalist groups press forward, the choice before educators, lawmakers, and citizens is clear: whether to preserve a civic culture rooted in freedom of conscience and open debate, or to accept an Americanized faith that substitutes nationalism for scripture. The stakes are not merely academic; they touch the future of democracy itself.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.26.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.