The lack of a Bill of Rights became an issue during Virginia’s ratification convention.

By Jessie Kratz

Historian

United States National Archives

During the period of the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, one of the biggest criticisms of the document was that it lacked a bill of rights. Some states included proposed amendments as part of their state’s ratifications, and the primary reason North Carolina didn’t initially ratify the Constitution was because it lacked protections for individual liberties and freedoms.

The lack of a Bill of Rights became an issue during Virginia’s ratification convention and then again during the election of members to the House of Representatives. James Madison was seeking election to the House, and to satisfy the calls for a Bill of Rights, Madison reluctantly agreed to support amendments as a representative from Virginia.

On June 8, 1789, during the First Federal Congress, Madison proposed several amendments to be interwoven into the text of the Constitution. He took them mostly from the more than 200 amendments proposed by the states during their ratification conventions.

In August the House debated, reworded, and changed the amendments. One important event occurred when Roger Sherman of Connecticut successfully proposed a resolution to make them a separate list and move them to the end of the Constitution rather than inserting them directly into the text.

On August 24 the House passed 17 proposed amendments, and then the Senate took up the matter, making several more changes of its own.

The House and the Senate then reconciled their differences in a conference committee. The House approved the amendments on September 24, and the Senate agreed on September 25, 1789—two-thirds of Congress had passed a final version with 12 proposed amendments.

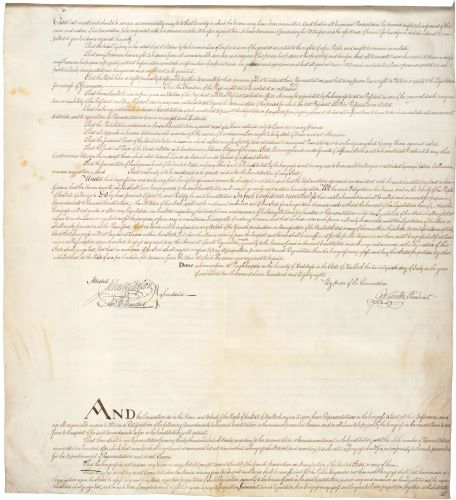

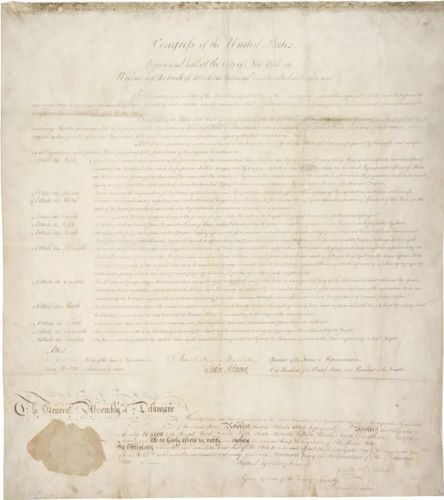

A few days later, Speaker of the House Frederick Muhlenberg and Vice President John Adams signed the enrolled joint resolution proposing the first amendments to the new Constitution—the document that later became known as the Bill of Rights (the one on display at the National Archives in Washington, DC).

Clerks also created 13 additional copies, which President George Washington sent to the 11 states and to Rhode Island and North Carolina—which had not yet adopted the Constitution. Three-fourths of the states needed to ratify the amendments to make them part of the Constitution.

Then began the slow ratification process, with states taking up each amendment individually over the next two years. New Jersey was the first state to act, passing amendments one and three through 12 on November 20, 1789, and then Maryland ratified all of the amendments on December 19, 1789.

Just a month after joining the union, North Carolina ratified all the amendments on December 22, 1789.

South Carolina then ratified all the amendments on January 19, 1790, New Hampshire ratified one and three through 12 on January 25, 1790, Delaware ratified two through 12 on January 28, 1790, New York ratified one and three through 12 on February 24, 1790, and on March 10, 1790, Pennsylvania ratified three through 12 (then revisited amendment one on September 21, 1791, and ratified that too).

On May 29, 1790, Rhode Island finally adopted the U.S. Constitution and a week later ratified amendments one and three through 12.

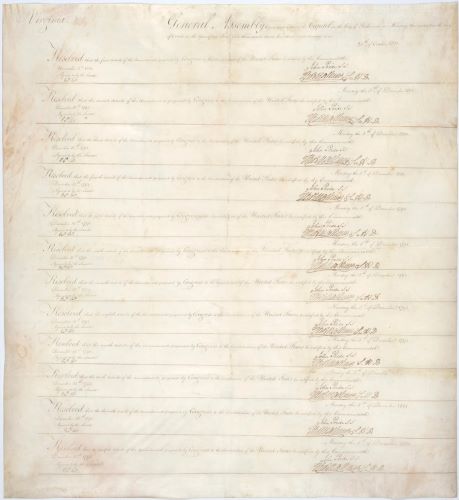

Then there was a huge gap in action. On March 4, 1791, Vermont became the 14th state but waited until November 3, 1791, to ratify all the proposed amendments. That day Virginia ratified amendment one, then on December 15, 1791, Virginia ratified two through 12.

With Virginia’s actions on December 15, 11 states had ratified amendments three through 12 to reach the three-fourths mark needed to make them law. The first 10 amendments had just been added to the Constitution.

What about the other two proposed amendments? The original first (proposed) amendment outlined representation in the House of Representatives—it allowed for one representative for every 50,000 people. The amendment came within one state of becoming adopted, but has not since been ratified by enough states to become part of the Constitution.

The original second amendment dealt with salaries of members of Congress—it said that Congress can’t raise their own pay without an intervening Congress. Six states initially approved it. Over time, however, states continued to ratify it, including Kentucky in 1792, Ohio in 1873, and Wyoming in 1978.

Then in the early 1980s, Gregory Watson, a student at the University of Texas at Austin, wrote a paper on the proposed amendment, arguing that it was still alive and began lobbying state legislatures to pass it. In 1983 Maine became the first state to ratify the amendment as a result of Watson’s efforts.

During the next several years, more states followed Maine’s lead until Michigan’s ratification on May 7, 1992. Michigan provided what was thought to be the 38th state ratification required—three-fourths of the states—to make it part of the Constitution (at that time, Kentucky’s 1792 ratification was unknown and therefore not counted).

The amendment went to the Archivist of the United States, who, since 1985, has been responsible for certifying constitutional amendments. On May 18, 1992, in a small ceremony in his office in the National Archives Building, Don Wilson became the first and only Archivist to certify a constitutional amendment. Effective May 7, 1992, the 27th Amendment became part of the U.S. Constitution.

So, when you visit the Bill of Rights in the Rotunda at the National Archives, you will see 12 amendments—the first 10 amendments that became the Bill of Rights (the original third through 12th amendments) and the original second (proposed) amendment which is now the 27th Amendment!

Originally published by Pieces of History, United States National Archives and Records Administration, 09.25.2019, to the public domain.